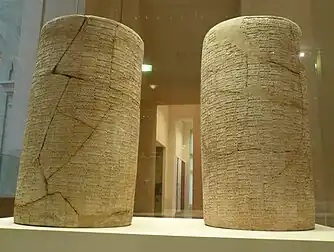

The Gudea cylinders are a pair of terracotta cylinders dating to c. 2125 BC, on which is written in cuneiform a Sumerian myth called the Building of Ningirsu's temple.[1] The cylinders were made by Gudea, the ruler of Lagash, and were found in 1877 during excavations at Telloh (ancient Girsu), Iraq and are now displayed in the Louvre in Paris, France. They are the largest cuneiform cylinders yet discovered and contain the longest known text written in the Sumerian language.[2]

Compilation

Discovery

The cylinders were found in a drain by Ernest de Sarzec under the Eninnu temple complex at Telloh, the ancient ruins of the Sumerian holy city of Girsu, during the first season of excavations in 1877. They were found next to a building known as the Agaren, where a brick pillar (pictured) was found containing an inscription describing its construction by Gudea within Eninnu during the Second Dynasty of Lagash. The Agaren was described on the pillar as a place of judgement, or mercy seat, and it is thought that the cylinders were either kept there or elsewhere in the Eninnu. They are thought to have fallen into the drain during the destruction of Girsu generations later.[3] In 1878 the cylinders were shipped to Paris, France where they remain on display today at the Louvre, Department of Near East antiquities, Richelieu, ground floor, room 2, accession numbers MNB 1511 and MNB 1512.[3]

Description

The two cylinders were labelled A and B, with A being 61 cm high with a diameter of 32 cm and B being 56 cm with a diameter of 33 cm. The cylinders were hollow with perforations in the centre for mounting. These were originally found with clay plugs filling the holes, and the cylinders themselves filled with an unknown type of plaster. The clay shells of the cylinders are approximately 2.5 to 3 cm thick. Both cylinders were cracked and in need of restoration and the Louvre still holds 12 cylinder fragments, some of which can be used to restore a section of cylinder B.[3] Cylinder A contains thirty columns and cylinder B twenty four. These columns are divided into between sixteen and thirty-five cases per column containing between one and six lines per case. The cuneiform was meant to be read with the cylinders in a horizontal position and is a typical form used between the Akkadian Empire and the Ur III dynasty, typical of inscriptions dating to the 2nd Dynasty of Lagash. Script differences in the shapes of certain signs indicate that the cylinders were written by different scribes.[3]

Translations and commentaries

Detailed reproductions of the cylinders were made by Ernest de Sarzec in his excavation reports which are still used in modern times. The first translation and transliteration was published by Francois Threau-Dangin in 1905.[4] Another edition with a notable concordance was published by Ira Maurice Price in 1927.[5] Further translations were made by M. Lambert and R. Tournay in 1948,[6] Adam Falkenstein in 1953,[7] Giorgio Castellino in 1977,[8] Thorkild Jacobsen in 1987,[1] and Dietz Otto Edzard in 1997.[9] The latest translation by the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL) project was provided by Joachim Krecher with legacy material from Hermann Behrens and Bram Jagersma.[10] Samuel Noah Kramer also published a detailed commentary in 1966[11] and in 1988.[12] Herbert Sauren proposed that the text of the cylinders comprised a ritual play, enactment or pageant that was performed during yearly temple dedication festivities and that certain sections of both cylinders narrate the script and give the ritual order of events of a seven-day festival.[13] This proposition was met with limited acceptance.[14]

Composition

.jpg.webp)

Interpretation of the text faces substantial limitations for modern scholars, who are not the intended recipients of the information and do not share a common knowledge of the ancient world and the background behind the literature. Irene Winter points out that understanding the story demands "the viewer's prior knowledge and correct identification of the scene – a process of 'matching' rather than 'reading' of imagery itself qua narrative." The hero of the story is Gudea (statue pictured), king of the city-state of Lagash at the end of the third millennium BC. A large quantity of sculpted and inscribed artifacts have survived pertaining to his reconstruction and dedication of the Eninnu, the temple of Ningursu, the patron deity of Lagash. These include foundation nails (pictured), building plans (pictured) and pictorial accounts sculpted on limestone stelae. The temple, Eninnu was a formidable complex of buildings, likely including the E-pa, Kasurra and sanctuary of Bau among others. There are no substantial architectural remains of Gudea's buildings, so the text is the best record of his achievements.[3]

Cylinder X

Some fragments of another Gudea inscription were found that could not be pieced together with the two in the Louvre. This has led some scholars to suggest that there was a missing cylinder preceding the texts recovered. It has been argued that the two cylinders present a balanced and complete literary with a line at the end of Cylinder A having been suggested by Falkenstein to mark the middle of the composition. This colophon has however also been suggested to mark the cylinder itself as the middle one in a group of three. The opening of cylinder A also shows similarities to the openings of other myths with the destinies of heaven and earth being determined. Various conjectures have been made regarding the supposed contents of an initial cylinder. Victor Hurowitz suggested it may have contained an introductory hymn praising Ningirsu and Lagash.[15] Thorkild Jacobsen suggested it may have explained why a relatively recent similar temple built by Ur-baba (or Ur-bau), Gudea's father-in-law "was deemed insufficient".[1]

Cylinder A

Cylinder A opens on a day in the distant past when destinies were determined with Enlil, the highest god in the Sumerian pantheon, in session with the Divine Council and looking with admiration at his son Ningirsu (another name for Ninurta) and his city, Lagash.[15]

Upon the day for making of decisions in matters of the world, Lagash in great office raised the head, and Enlil looked at Lord Ningirsu truly, was moved to have the things appropriate appear in our city.[1]

Ningirsu responds that his governor will build a temple dedicated to great accomplishments. Gudea is then sent a dream where a giant man – with wings, a crown, and two lions – commanded him to build the E-ninnu temple. Two figures then appear: a woman holding a gold stylus, and a hero holding a lapis lazuli tablet on which he drew the plan of a house. The hero placed bricks in a brick mold and carrying basket, in front of Gudea – while a donkey gestured impatiently with its hoof. After waking, Gudea could not understand the dream so traveled to visit the goddess Nanse by canal for interpretation of the oracle. Gudea stops at several shrines on the route to make offerings to various other deities. Nanse explains that the giant man is her brother Ningirsu, and the woman with the golden stylus is Nisaba goddess of writing, directing him to lay out the temple astronomically aligned with the "holy stars". The hero is Nindub an architect-god surveying the plan of the temple. The donkey was supposed to represent Gudea himself, eager to get on with the building work.[11]

Nanse instructs Gudea to build Ningirsu – a decorated chariot with emblem, weapons, and drums, which he does and takes into the temple with "Ushumgalkalama", his minstrel or harp (bull-shaped harp sound-box pictured). He is rewarded with Ningirsu's blessing and a second dream where he is given more detailed instructions of the structure. Gudea then instructs the people of Lagash and gives judgement on the city with a 'code of ethics and morals'. Gudea takes to the work zealously and measures the building site, then lays the first brick in a festive ritual. Materials for the construction are brought from over a wide area including Susa, Elam, Magan Meluhha and Lebanon. Cedars of Lebanon are apparently floated down from Lebanon on the Euphrates and the "Iturungal" canal to Girsu.

To the mountain of cedars, not for man to enter, did for Lord Ningirsu, Gudea bend his steps: its cedars with great axes he cut down, and into Sharur ... Like giant serpents floating on the water, cedar rafts from the cedar foothills.[1]

He is then sent a third dream revealing the different form and character of the temples. The construction of the structure is then detailed with the laying of the foundations, involving participation from the Anunnaki including Enki, Nanse, and Bau. Different parts of the temple are described along with its furnishings and the cylinder concludes with a hymn of praise to it.[11]

Lines 738 to 758 describe the house being finished with "kohl" and a type of plaster from the "edin" canal:

The fearsomeness of the E-ninnu covers all the lands like a garment! The house! It is founded by An on refined silver! It is painted with kohl, and comes out as the moonlight with heavenly splendor! The house! Its front is a great mountain firmly grounded! Its inside resounds with incantations and harmonious hymns! Its exterior is the sky, a great house rising in abundance! Its outer assembly hall is the Anunnaki gods place of rendering judgments – from its ...... words of prayer can be heard! Its food supply is the abundance of the gods! Its standards erected around the house are the Anzu bird (pictured) spreading its wings over the bright mountain! E-ninnu's clay plaster, harmoniously blended clay taken from the Edin canal, has been chosen by Lord Nin-jirsu with his holy heart, and was painted by Gudea with the splendors of heaven as if kohl were being poured all over it.[18]

Thorkild Jacobsen considered this "Idedin" canal referred to an unidentified "Desert Canal", which he considered "probably refers to an abandoned canal bed that had filled with the characteristic purplish dune sand still seen in southern Iraq."[1]

Cylinder B

The second cylinder begins with a narrative hymn starting with a prayer to the Anunnaki. Gudea then announces the house ready for the accommodation of Ningirsu and his wife Bau. Food and drink are prepared, incense is lit and a ceremony is organized to welcome the gods into their home. The city is then judged again and a number of deities are appointed by Enki to fill various positions within the structure. These include a gatekeeper, bailiff, butler, chamberlain, coachman, goatherd, gamekeeper, grain and fisheries inspectors, musicians, armourers and a messenger. After a scene of sacred marriage between Ningirsu and Bau, a seven-day celebration is given by Gudea for Ningirsu with a banquet dedicated to Anu, Enlil and Ninmah (Ninhursag), the major gods of Sumer, who are all in attendance. The text closes with lines of praise for Ningirsu and the Eninnu temple.[11]

The building of Ningirsu's temple

The modern name for the myth contained on both cylinders is "The building of Ningirsu's temple". Ningirsu was associated with the yearly spring rains, a force essential to early irrigation agriculture. Thorkild Jacobsen describes the temple as an intensely sacred place and a visual assurance of the presence of the god in the community, suggesting the structure was "in a mystical sense, one with him." The element "Ninnu" in the name of the temple "E-Ninnu" is a name of Ningirsu with the full form of its name, "E-Ninnu-Imdugud-babbara" meaning "house Ninnu, the flashing thunderbird". It is directly referred to as thunderbird in Gudea's second dream and in his blessing of it.[1]

Later use

Preceded by the Kesh temple hymn, the Gudea cylinders are one of the first ritual temple building stories ever recorded. The style, traditions and format of the account has notable similarities to those in the Bible such as the building of the tabernacle of Moses in Exodus 25 and Numbers 7.[19] Victor Hurowitz has also noted similarities to the later account of the construction of Solomon's temple in 1 Kings 6:1–38, 1 Kings Chapter 7, and Chapter 8 and in the Book of Chronicles.[15]

See also

- Sumerian literature

- Babylonian literature

- Atra-Hasis

- Sumerian creation myth

- Deluge (mythology)

- Gilgamesh flood myth

- The Garden of Eden

- Barton Cylinder

- Debate between sheep and grain

- Debate between bird and fish

- Debate between Winter and Summer

- Enlil and Ninlil

- Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D)

- Old Babylonian oracle

- Hymn to Enlil

- Kesh temple hymn

- Lament for Ur

- Sumerian religion

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Thorkild Jacobsen (1997). The Harps that once--: Sumerian poetry in translation, pp. 386-. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07278-5.

- ↑ Jeremy A. Black; Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson (2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Claudia E. Suter (2000). Gudea's temple building: the representation of an early Mesopotamian ruler in text and image. BRILL. p. 1. ISBN 978-90-5693-035-6.

- ↑ François Thureau-Dangin (1905). Les inscriptions de Sumer et d'Akkad. Ernest Leroux.

- ↑ Ira M. Price, "The great cylinder inscriptions A & B of Gudea: copied from the original clay cylinders of the Telloh Collection preserved in the Louvre. Transliteration, translation, notes, full vocabulary and sign-lifts", Volume 1 Volume 2, Hinrichs, 1899

- ↑ M. Lambert and R. Tournay, "Le Cylindre A de Gudea," 403–437; "Le Cylindre B de Gudea," 520–543. Revue Biblique, LV, pp. 403–447 & pp. 520–543, 1948.

- ↑ Adam Falkenstein (1953). Sumerische und akkadische Hymnen und Gebete. Artemis-Verlag.

- ↑ Giorgio. R. Castellino (1977). Testi sumerici e accadici. Unione tipografico-editrice torinese, Turin. ISBN 978-88-02-02440-0.

- ↑ Dietz Otto Edzard (1997). Gudea and his dynasty. University of Toronto Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8020-4187-6.

- ↑ The building of Ningirsu's temple., Biography, Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998–.

- 1 2 3 4 Samuel Noah Kramer (1964). The Sumerians: their history, culture and character. University of Chicago Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ↑ Michael V. Fox (1988). Temple in society. Eisenbrauns. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-931464-38-6.

- ↑ Herbert Sauren (1975). 'Die Einweihung des Eninnu', pp. 95–103, in Le temple et le culte: compte rendu de la vingtième rencontre assyriologique internationale organisée à Leiden du 3 au 7 juillet 1972 sous les auspices du Nederlands instituut voor het nabije oosten. Nederlands Historisch-Archeologisch Instituut te Istambul.

- ↑ Michael C. Astour; Gordon Douglas Young; Mark William Chavalas; Richard E. Averbeck, Kevin L. Danti (1997). Crossing boundaries and linking horizons: studies in honor of Michael C. Astour on his 80th birthday. CDL Press. ISBN 978-1-883053-32-1.

- 1 2 3 Victor Hurowitz (1992). I have built you an exalted house: temple building in the Bible in the light of Mesopotamian and North-West semitic writings. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 1–57. ISBN 978-1-85075-282-0.

- ↑ "I will spread in the world respect for my Temple, under my name the whole universe will gather in it, and Magan and Meluhha will come down from their mountains to attend" "J'étendrai sur le monde le respect de mon temple, sous mon nom l'univers depuis l'horizon s'y rassemblera, et [même les pays lointains] Magan et Meluhha, sortant de leurs montagnes, y descendront" (cylinder A, IX:19)" in "Louvre Museum".

- ↑ "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk.

- ↑ The building of Ningirsu's temple., Cylinder A, Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998–. Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mark W. Chavalas (2003). Mesopotamia and the Bible. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-567-08231-2.

Further reading

- Edzard, D.O., Gudea and His Dynasty (The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods, 3, I). Toronto/Buffalo/London: University of Toronto Press, 68–101, 1997.

- Falkenstein, Adam, Grammatik der Sprache Gudeas von Lagas, I-II (Analecta Orientalia, 29–30). Roma: Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, 1949–1950.

- Falkenstein, Adam – von Soden, Wolfram, Sumerische und akkadische Hymnen und Gebete.Zürich/Stuttgart: Artemis, 192–213, 1953.

- Jacobsen, Th., The Harps that Once ... Sumerian Poetry in Translation. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 386–444: 1987.

- Suter, C.E., "Gudeas vermeintliche Segnungen des Eninnu", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 87, 1–10: partial source transliteration, partial translation, commentaries, 1997.

- Witzel, M., Gudea. Inscriptiones: Statuae A-L. Cylindri A & B. Roma: Pontificio Isituto Biblico, fol. 8–14,1, 1932.

External links

Media related to Gudea cylinders at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gudea cylinders at Wikimedia Commons- Louvre – The Gudea Cylinders

- Cylinder A – The building of Ningirsu's temple., Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998–.

- Cylinder B – The building of Ningirsu's temple., Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998–.

- Composite text of Cylinder A: "The building of Ningirsu's temple, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998–.

- CDLI Full transcription of Cylinder A

- CDLI Full transcription of Cylinder B

- Composite text of Cylinder B: "The building of Ningirsu's temple, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998–.

- Bibliography – The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998–.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_Magan_Meluha_with_transcription.jpg.webp)