_-_WGA25700.jpg.webp)

Guillaume Fillastre or Fillâtre (died 1473) was a Burgundian statesman, prelate and patron of arts. He served as a counsellor to Duke Philip the Good and was successively bishop of Verdun (1437–1448), bishop of Toul (1448–1460) and bishop of Tournai (1460–1473). He was also the abbot of Saint-Bertin from 1451 until his death.

Life

Fillastre was born in Châlons-en-Champagne.[1] He was an illegitimate child, but the identities of his parents are uncertain. There were rumours that he was a son of Philip the Good.[2] He is sometimes called "the younger" to distinguish him from Cardinal Guillaume Fillastre, "the elder".[1] According to some, he was the son[1] or nephew of the cardinal.[3]

Fillastre became a Benedictine oblate at Châlons in childhood.[1][2] He studied canon law at the universities of Bologna and Paris.[1] In 1431, he served Duke René I of Anjou as an envoy to Pope Eugene IV at the Council of Basel. In 1436, he received his doctorate from the University of Louvain. Through the influence of Philip the Good and over much opposition, he became bishop of Verdun in 1437.[2] In 1440, Philip made him his chancellor.[1] In 1442, he named him abbot in commendam of the Abbey of Saint-Bertin over opposition. The monks yielded only to the implied threat of violence when Philip showed up in person in 1447–1448.[2][4] Pope Nicholas V confirmed Fillastre as abbot in 1451.[2]

Fillastre was especially close to the duchess of Burgundy, Isabella of Portugal.[1] He was sent to Italy on embassies from Philip in 1444, 1448, 1451 and 1464. In 1448, he was transferred from Verdun to the diocese of Toul.[2] In 1444, he attended the Diet of Nuremberg.[5] In 1454, he was Philip's delegate at the Imperial Diet held to discuss the crusade against the Turks.[1] In 1456, Philip designated him as the successor to the diocese of Tournai, where Bishop Jean Chevrot's health was failing.[2] In 1457, Philip named him president of the ducal council (chef du conseil).[1] In 1460, he succeeded Chevrot in an exchange of sees.[6][7] Chevrot resigned Tournai in return for appointment to Toul. Charles VII of France objected and had Fillastre brought before the Parlement of Paris, but Chevrot died before the end of the year and Pope Pius II confirmed Fillastre as bishop of Tournai.[7]

Fillastre lost influence in the Burgundian court after Charles the Bold seized power in March 1465, although he retained his posts of chancellor and chef du conseil until his death.[1] He celebrated Mass and delivered the eulogy at Philip's funeral in 1467.[8] Thereafter his influence at the Burgundian court declined. He died in 1473 and was buried, in accordance with his will, in the nave of Saint-Bertin in front of the altarpiece he had commissioned.[2]

Writings

Fillastre served Philip as chancellor of the Order of the Golden Fleece from 1461.[1][9] He composed a liturgical office for the order and his greates work, never finished, is the Histoire de Toison d'Or ('history of the golden fleece'). It was projected to be six volumes, each on a different famous fleece. Only three were completed: on the Golden Fleece, on the fleece from the flocks of Laban and on the fleece of Gideon. The work was dedicated to Philip's successor, Charles the Bold.[2] Malte Prietzel calls it "a vast treatise on the moral and theological bases of politics" misleadingly titled.[1]

Fillastre wrote another political treatise, Bref et utile traité de conseil ('brief and useful treatise on counsel').[2]

There are records of 39 speeches Fillastre delivered in his career, although this must be only a fraction of the total. He spoke in French to Burgundian audiences and Latin to foreign ones. Seven of his speeches are preserved complete: four in the original Latin, two in the original French and one in a French translation of a lost Latin original.[10]

Art patronage

In 1455, Fillastre commissioned an altarpiece for Saint-Bertin. It was destroyed during the French Revolution after 1791. Only its two painted wooden shutters survive.[11] Edith Warren Hoffman describes the lost work as Fillastre's greatest commission: "The format of the altarpiece is noteworthy in that it consisted of a combination of gilded silver sculpture and paintings in an architectural framework; it was a type of Gesamtkunstwerk. As such, it belongs to a category quite distinct from altarpieces made exclusively of painted panels."[12]

Fillastre was a prolific commissioner of tapestries. Some twenty fragments of a tapesty commissioned for Tournai Cathedral in 1460 are all that survives of these works. They are now in the Musée de l'hôtel Sandelin. He gave a tapestry depicting the Passion of Christ to Verdun Cathedral and another to Toul Cathedral. In his will, he left behind five personal tapestries depicting falconry, ladies under canopies, Amis et Amiles, and the stories of Lucretia and David. In addition, he granted two embroidered copes to Tournai Cathedral, one of which survives.[13]

In imitation of his Burgundian masters, Fillastre also commissioned goldwork. Two gold reliquary busts for his abbey are known. In 1462, he ordered one for Saint Bertin. It was completed in 1464, but was lost during the Revolution. The reliquary for Mummolin of Noyon was ordered in 1466 and still exists.[14]

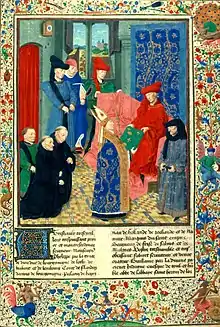

Fillastre probably also commissioned illuminated manuscripts, although only one is known for certain. The Saint Petersburg Grandes Chroniques de France was commissioned as a gift for Philip the Good and contains a presentation miniature showing Fillastre handing the manuscript to the duke. Fillastre appears to have edited the text himself.[13]

Towards the end of his life, Fillastre commissioned the Della Robbia of Florence to sculpt his tomb. It was brought to Saint-Bertin in 1470–1471. In his will, he stipulated that his tomb should only be erected if the professors of theology affirmed that it was not an act of vanity. The tomb was installed.[15]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Prietzel 2006, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hoffman 1978, p. 639.

- ↑ Häyrynen 1994, p. 5.

- ↑ Vaughan 1970, p. 235.

- ↑ Prietzel 2006, p. 120.

- ↑ Van Eeckenrode 2009.

- 1 2 Vaughan 1970, p. 220.

- ↑ Prietzel 2006, p. 117.

- ↑ Vaughan 1970, p. 128.

- ↑ Prietzel 2006, p. 121.

- ↑ Hoffman 1978, pp. 634–636.

- ↑ Hoffman 1978, p. 645.

- 1 2 Hoffman 1978, p. 642.

- ↑ Hoffman 1978, pp. 642–643.

- ↑ Hoffman 1978, p. 641.

Bibliography

- Häyrynen, Helena, ed. (1994). Guillaume Fillastre, Le traittié de conseil: édition critique avec introduction, commentaire et glossaire. University of Jyväskylä.

- Hoffman, Edith Warren (1978). "A Reconstruction and Reinterpretation of Guillaume Fillastre's Altarpiece of St.-Bertin". The Art Bulletin. 60 (4): 634–649. doi:10.1080/00043079.1978.10787612.

- Prietzel, Malte (2001). Guillaume Fillastre der Jüngere (1400/07–1473): Kirchenfürst und herzoglich-burgundischer Rat. Thorbecke.

- Prietzel, Malte (2006). "Rhetoric, Politics and Propaganda: Guillaume Fillastre's Speeches". In Jonathan Boulton; Jan Veenstra (eds.). The Ideology of Burgundy: The Promotion of National Consciousness, 1364–1565. Brill. pp. 117–129. doi:10.1163/9789047418498_005.

- Van Eeckenrode, Marie (2009). "Le testament de Jean Chevrot, président du conseil de Philippe le Bon, évêque de Tournai (1438–1460), enfant de Poligny". In J. Pycke; A. Dupont (eds.). Archives et manuscrits précieux tournaisiens. Vol. 3. Université Catholique de Louvain. pp. 7–34.

- Vaughan, Richard (1970). Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. Longmans.