Baralong in Bucknall Lines colours | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake | |

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | |

| Builder | Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd, Low Walker |

| Yard number | 711 |

| Launched | 12 September 1901 |

| Completed | November 1901 |

| Commissioned | into Royal Navy, March 1915 |

| Decommissioned | out of Royal Navy, October 1916 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scrapped 1933 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Cargo ship |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 360.0 ft (109.7 m) |

| Beam | 47.0 ft (14.3 m) |

| Depth | 28.3 ft (8.6 m) |

| Decks | 2 |

| Installed power | 535 NHP |

| Propulsion | triple expansion engine |

| Speed | 12 knots (22 km/h) |

| Armament |

|

| Notes | sister ships: Manica, Barotse, Bantu |

HMS Baralong was a cargo steamship that was built in England in 1901, served in the Royal Navy as a Q-ship in the First World War, was sold into Japanese civilian service in 1922 and scrapped in 1933. She was renamed HMS Wyandra in 1915, Manica in 1916, Kyokuto Maru in 1922 and Shinsei Maru No. 1 in 1925.

As a Q-ship, Baralong was both successful and controversial. In 1915 she sank two U-boats: U-27 in August and U-41 in September, in two engagements that are known as the Baralong incidents. The circumstances of the sinkings led Germany to describe both incidents as war crimes.

Building

In 1900 and 1901 Bucknall Steamship Lines Ltd took delivery of a set of four new sister ships from two shipbuilders in North East England. In 1900 Sir James Laing & Sons Ltd at Sunderland on the River Wear launched Manica on 25 September and Barotse on 22 December.[1][2] In 1901 Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd at Low Walker on the River Tyne launched Bantu on 16 July and Baralong on 12 September.[3][4] All four ships were named after peoples or places in southern Africa, where Bucknall traded.

The four ships were built to almost identical dimensions. Baralong's registered length was 360.0 ft (109.7 m), her beam was 47.0 ft (14.3 m) and her depth was 28.3 ft (8.6 m). Her tonnages were 4,192 GRT and 2,661 NRT. The Wallsend Slipway & Engineering Company built her engine, which was a three-cylinder triple expansion steam engine rated at 535 NHP.[5]

Armstrong, Whitworth completed Baralong in November 1901. Bucknall's registered her in London. Her UK official number was 114788 and her code letters were SWMN.[5]

Bucknall's service

On 8 September 1902 Baralong left Britain towing a 30,000 DWT floating dock to be delivered to Durban in Natal. The dock was so large that Baralong's speed was limited to 5 knots (9.3 km/h). She got as far as Mossel Bay in Cape Colony, where the towing line broke in bad weather. The floating dock was driven ashore and wrecked.[6]

On 22 August 1905 Baralong collided with the Japanese ferry Kinjo Maru off Shimishima, killing 160 people. An inquiry found that Kinjo Maru had failed to display the correct navigation lights.[6]

By 1908 Bucknall was over-extended, so JR Ellerman stepped in to support the company. In January 1914 Bucknall became a subsidiary of his Ellerman Lines shipping group, and was renamed Ellerman & Bucknall.[7]

Requisitioning and naval conversion

In August[4] or September[6] 1914 the Admiralty requisitioned Baralong as a naval supply ship. In March 1915 she arrived at Barry Docks for conversion into a "Special Service Vessel" or Q-ship. She was armed with three 12-pounder naval guns in concealed mountings, equipped with devices to simulate damage, and otherwise modified for naval service.[8] In April 1915 work was completed, and she was commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Baralong.[9]

Baralong's task was to lure and engage U-boats. Her first commander was Cdr Godfrey Herbert, who had a decade of experience in the Royal Navy Submarine Service, and was chosen to be a "poacher turned gamekeeper". His crew were volunteers for the mission.[9] Baralong spent the next four months patrolling the Southwest Approaches, seeking to lure a U-boat attack.

Baralong incidents

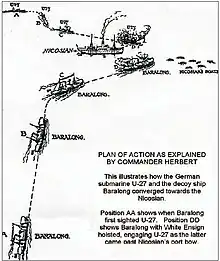

On 19 August 1915 the White Star passenger liner Arabic sent a wireless telegraph distress signal that a submarine was attacking her. Baralong received the signal and headed for Arabic's reported position. Arabic sank without the Q-ship reaching her, but after several hours Baralong found the Leyland Line cargo ship Nicosian, which U-27 had stopped, boarded, and was inspecting under the cruiser rules. Flying a neutral United States flag as a disguise, the Q-ship approached Nicosian, signalling that she intended to rescue survivors.

When Baralong closed on Nicosian she lowered her US flag, raised her White Ensign, exposed her concealed guns and opened fire on U-27. Baralong's crew then opened fire with small arms, killing the German crew as they escaped the U-boat or tried to climb aboard Nicosian. Baralong then put a boarding party aboard Nicosian, where they pursued and killed U-27's boarding party.

Nicosian's complement included neutral US citizens, most of whom were muleteeers looking after the mules that formed part of her cargo. When they returned to the USA that October, they revealed the circumstances in which Baralong's crew had killed the German submariners. The German Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, condemned the killings.[10][11]

After the incident, Cdr Herbert was transferred back to the Submarine Service. Lt Cdr A Wilmot-Smith succeeded him in command of Baralong, which continued to patrol the Southwest Approaches. On 21 September 1915 U-41 attacked Wilson Line's cargo steamship Urbino. Baralong approached, again flying a US flag to feign neutrality. U-41 submerged, then resurfaced and ordered Baralong to stop.

Baralong obeyed, but then exposed her guns and opened fire, hitting U-41. The submarine dived, then resurfaced a second time. Only two of the German crew escaped before the U-boat sank. One was the First Officer, OLt zS Iwan Crompton, who was seriously wounded. Crompton was repatriated to Germany, where he alleged that Baralong attacked without lowering her US false flag.

In 1920 Baralong's Royal Navy crew was awarded prize money for sinking U-27 and U-41. The London Gazette recorded the awards under the name HMS Wyandra.[12]

Further war service

The "Baralong Incidents" provoked outrage in Germany. In October 1915 Baralong was renamed HMS Wyandra to conceal her identity.[4] She was transferred to the Mediterranean to join a Q-ship force being established there.

In November 1916 the Admiralty returned Wyandra to Ellerman & Bucknall, who renamed her again. In 1915 the Admiralty had requisitioned her sister ship Manica as a kite balloon ship, so Ellerman transferred the name Manica to Wyandra.[1]

Japanese service

In 1922[4] or '23[6] Ellerman & Bucknall sold Manica to Kyokuto Koshi Goshi Kaisha of Japan. Goshi Kaisha renamed her Kyokuto Maru and registered her in Dairen in the Kwantung Territory. In 1925 her ownership passed to Hara Shoji KK, who renamed her Shinsei Maru No. 1. In 1926 she changed hands again to Shinsei Kisen Goshi Kaisha.[4] She remained registered in Dairen, and her Japanese code letters were QBPJ.

Shinsei Maru No. 1 was scrapped in Japan in 1933[4] or '34.[6][13]

References

- 1 2 "Manica". Wear Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ "Barotse". Wear Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ "Bantu". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Baralong". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- 1 2 "Steamers". Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1914.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Collard 2014, p. 199

- ↑ Collard 2014, p. 21.

- ↑ Colledge 1970

- 1 2 Ritchie 1985, p. 33.

- ↑ "Denies Baralong charge". The New York Times. 11 December 1915. p. 7. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ "Memorandum of the German Government in regard to incidents alleged to have attended the destruction of a German submarine and its crew by His Majesty's auxiliary cruiser "Baralong" on August 19, 1915, and reply of His Majesty's Government thereto". WWI Virtual Library. January 1916. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ↑ "Notice of intended distribution of naval prize bounty money". The London Gazette. No. 31972. 9 July 1920. p. 7353.

- ↑ "Steamers and Motorships". Lloyd's Register of Shipping (PDF). Vol. II. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1933 – via Southampton City Council.

Bibliography

- Collard, Ian (2014). Ellerman Lines Remembering a Great British Company. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-8963-6.

- Colledge, JJ (1970). Ships of the Royal Navy: An historical index. Vol. 2. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0715343963.

- Ritchie, Carson (1985). Q-Ships. ISBN 0-86138-011-8.