Benbow underway | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Benbow |

| Namesake | John Benbow |

| Ordered | 1911 |

| Builder | William Beardmore and Company, Glasgow |

| Laid down | 30 May 1912 |

| Launched | 12 November 1913 |

| Commissioned | 7 October 1914 |

| Decommissioned | 1929 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, March 1931 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Iron Duke-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 622 ft 9 in (189.8 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 90 ft (27.4 m) |

| Draught | 29 ft 6 in (9.0 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21.25 knots (39.4 km/h; 24.5 mph) |

| Range | 7,800 nmi (14,446 km; 8,976 mi) at 10 knots (18.5 km/h; 11.5 mph) |

| Complement | 995–1,022 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Benbow was the third of four Iron Duke-class battleships of the Royal Navy, the third ship to be named in honour of Admiral John Benbow.[1] Ordered in the 1911 building programme, the ship was laid down at the William Beardmore and Company shipyard in May 1912, was launched in November 1913, and was completed in October 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War. The four Iron Dukes were very similar to the preceding King George V class, with an improved secondary battery. She was armed with a main battery of ten 13.5-inch (343 mm) guns and twelve 6 in (152 mm) secondary guns. The ship was capable of a top speed of 21.25 knots (39.36 km/h; 24.45 mph), and had a 12-inch (305 mm) thick armoured belt.

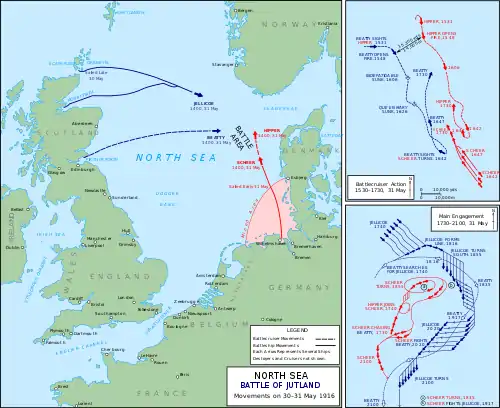

Benbow served in the Grand Fleet as the flagship of the 4th Battle Squadron during the war. She was present during the largest naval action of the war, the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, though she was not heavily engaged. She sortied twice more, in August 1916 and April 1918 in attempts to catch the German High Seas Fleet in another major battle, but neither produced any significant action. After the end of the war in 1918, Benbow and the rest of the 4th Squadron were reassigned to the Mediterranean Fleet. There, she took part in operations in the Black Sea in support of White Russians in the Russian Civil War until mid-1920, when the Mediterranean Fleet began supporting Greek forces during the Greco-Turkish War. In 1926, Benbow was reassigned to the Atlantic Fleet. She was decommissioned in 1929, placed on the sale list in September 1930, and sold for scrap the following year.

Design

The four Iron Duke-class battleships were ordered in the 1911 building programme, and were an incremental improvement over the preceding King George V class. The primary change between the two designs was the substitution of a heavier secondary battery in the newer vessels. Benbow was 622 ft 9 in (190 m) long overall, and she had a beam of 90 ft (27 m) and an average draught of 29 ft 6 in (9 m). She displaced 25,000 long tons (25,401 t) as designed and up to 29,560 long tons (30,034 t) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of four Parsons steam turbines, with steam provided by eighteen Babcock & Wilcox boilers. Benbow had a fuel storage capacity of 3,200 long tons (3,300 t) of coal and 1,030 long tons (1,050 t) of oil. The engines were rated at 29,000 shp (21,625 kW) and produced a top speed of 21.25 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). Her cruising radius was 7,800 nmi (14,446 km; 8,976 mi) at a more economical 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Benbow had a crew of 995 officers and ratings, though during wartime this grew to up to 1,022.[2]

Benbow was armed with a main battery of ten BL 13.5-inch (343 mm) Mk V naval guns mounted in five twin gun turrets all on the centerline. They were arranged in two superfiring pairs, one forward with "A" and "B" turrets and one aft of the superstructure with "X" and "Y" turrets; the fifth turret, "P", was located amidships, between the funnels and the rear superstructure. Close-range defence against torpedo boats was provided by a secondary battery of twelve BL 6-inch Mk VII guns, which were mounted in casemates in the hull clustered around the forward superstructure. The ship was also fitted with a pair of QF 3-inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft guns and four 47 mm (2 in) 3-pounder guns.[Note 1] As was typical for capital ships of the period, she was equipped with four 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes submerged on the broadside.[2]

Benbow was protected by a main armoured belt that was 12 in (305 mm) thick over the ship's ammunition magazines and engine and boiler rooms, and reduced to 4 in (102 mm) toward the bow and stern. Her deck was 2.5 in (64 mm) thick in the central portion of the ship, and reduced to 1 in (25 mm) elsewhere. The main battery turret faces were 11 in (279 mm) thick, and the turrets were supported by 10 in (254 mm) thick barbettes.[2]

Service history

First World War

.tiff.jpg.webp)

The keel for Benbow was laid down at the William Beardmore and Company shipyard on 30 May 1912. Her completed hull was launched on 12 November 1913, and fitting out work was completed by October 1914, just two months after the outbreak of the First World War.[2] On 1 December, Benbow and her sister ship HMS Emperor of India arrived at the 4th Battle Squadron to begin working up, before being pronounced fit for service with the fleet on 10 December.[3] During this period, the rearmost 6-inch guns were removed from the four Iron Duke-class ships and their casemates were sealed off, as they were too low in the hull and permitted water to continually enter the ship.[4] On the 10th, she replaced Dreadnought as the flagship of the 4th Squadron.[5] On 23–24 December, the 4th and 2nd Squadrons conducted gunnery practice north of the Hebrides.[6] The following day, the entire fleet sortied for a sweep in the North Sea, which concluded on 27 December; this was Benbow's first fleet operation.[7]

Another round of gunnery drills followed on 10–13 January 1915 west of Orkney and Shetland, this time with the entire fleet.[8] On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Vice Admiral David Beatty's Battlecruiser Fleet, but the main fleet did not become engaged in the Battle of Dogger Bank that took place the following day.[9] On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet conducted a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place from 16–19 March.[10] On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place from 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.[11] The Grand Fleet conducted a sweep into the central North Sea from 17–19 May without encountering any German vessels.[12] In mid-June, the fleet conducted another round of gunnery training.[13] On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills.[14] Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises.[15] On 13 October, the majority of the fleet conducted another sweep into the North Sea, returning to port on the 15th.[16] From 2–5 November, Benbow participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney.[17] Another such cruise took place from 1–4 December.[18]

Benbow was occupied with the typical routine of gunnery drills and squadron exercises in January.[19] The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Admiral John Jellicoe, the commander of the Grand Fleet, had intended to use the Harwich Force to sweep the Heligoland Bight, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea.[20] On the night of 25 March, Benbow and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support the Battlecruiser Fleet and other light forces that raided the German zeppelin base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a severe gale threatened the light craft. Iron Duke, the fleet flagship, guided the destroyers back to Scapa while Benbow and the rest of the fleet retired independently.[21] On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Russian Navy relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea.[22] The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft. The Grand Fleet did not arrive in the area until after the German High Seas Fleet had withdrawn, however.[23][24] From 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea.[25]

Battle of Jutland

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet with sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts, six light cruisers and thirty-one torpedo boats commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, departed the Jade early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers and supporting cruisers and torpedo boats.[26] The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. The Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, at that time consisting of twenty-eight dreadnoughts and nine battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[27] At the time of the battle, the ship's commander was Captain Henry Wise Parker,[28] and she was the flagship of Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee. She was stationed toward the center of the British line.[29] The initial action was fought primarily by the British and German battlecruiser formations in the afternoon,[30] but by 18:00, the Grand Fleet approached the scene.[31]

At about 18:15, Jellicoe gave the order to turn and deploy the fleet for action.[32] At 18:30, Benbow opened fire, but her gunners were frequently hampered by poor visibility; her two forward turrets fired only six two-gun salvos over the course of the next ten minutes without any success.[33] Shortly thereafter, German torpedo boats attempted to rescue the crew from the light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden, which had been disabled between the opposing fleets, though they appeared to the British to be launching an attack against the Grand Fleet. Benbow and several other battleships opened fire with their secondary batteries, starting at 19:09. Despite the fusillade from eight battleships, none of the torpedo boats were hit, though they were forced to abandon Wiesbaden.[34] The ship fired six salvos from her main battery between 19:17 and 19:25, the first from two of her forward guns to confirm the range, and then four 5-gun and one 4-gun salvo in rapid succession. The gunners incorrectly claimed to have hit the battlecruiser SMS Derfflinger.[35] At around that time, Benbow and three other battleships opened fire with their secondary guns on a group of torpedo boats that were launching an attack on the British line. The vessels made four hits, but in the confusion, credit for the hits could not be given.[36]

Following the German torpedo boat attack, the High Seas Fleet disengaged, and Benbow and the rest of the Grand Fleet saw no further significant action in the battle. This was, in part, due to poor communication between Jellicoe and his subordinates over the exact location and course of the German fleet; without this information, Jellicoe could not bring his fleet to action.[37] Benbow fired briefly at a group of torpedo boats at about 21:10, with a salvo of 6-inch shells and a single 13.5-inch round.[38] At 21:30, the Grand Fleet began to reorganise into its nighttime cruising formation.[39] Early on the morning of 1 June, the Grand Fleet combed the area, looking for damaged German ships, but after spending several hours searching, they found none.[40] In the course of the battle, Benbow had fired forty 13.5-inch armour-piercing, capped shells and sixty 6-inch rounds.[41]

Later operations

Upon returning to port, Benbow was relieved as the squadron flagship, thereafter serving as a private ship.[5] In July, the ship received additional deck armour, primarily over the ammunition magazines. The work was completed by August.[42] On 18 August, the Germans again sortied, this time to bombard Sunderland; Scheer again hoped to draw out Beatty's battlecruisers and destroy them. British signals intelligence decrypted German wireless transmissions, allowing Jellicoe enough time to deploy the Grand Fleet in an attempt to engage in a decisive battle. Both sides withdrew, however, after their opponents' submarines inflicted losses in the action of 19 August 1916: the British cruisers Nottingham and Falmouth were both torpedoed and sunk by German U-boats, and the German battleship SMS Westfalen was damaged by the British submarine E23. After returning to port, Jellicoe issued an order that prohibited risking the fleet in the southern half of the North Sea due to the overwhelming risk from mines and U-boats.[43]

In late 1917, the Germans began using destroyers and light cruisers to raid the British convoys to Norway; this forced the British to deploy capital ships to protect the convoys. In April 1918, the German fleet sortied in an attempt to catch one of the isolated British squadrons, though the convoy had already passed safely. The Grand Fleet sortied too late to catch the retreating Germans, though the battlecruiser SMS Moltke was torpedoed and badly damaged by the submarine E42.[44] A series of minor modifications were made to Benbow throughout 1917 and 1918; these included the installation of larger and additional searchlights to improve night combat capabilities and rangefinder baffles that were intended to make it more difficult to estimate the range for enemy gunners. The baffles were later removed in 1918, and flying-off ramps were erected on "B" and "Q" turrets.[45]

Postwar

After the war, the Grand Fleet was dissolved, and Benbow was assigned to the 4th Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet, where she served until March 1926. In 1919, Captain Charles Douglas Carpendale took command of the ship, a position he held until 1921.[46] During this period, from April 1919 to June 1920, the ship took part in anti-communist operations in the Black Sea. Benbow and other elements of the Mediterranean Fleet supported the White Russians in the Russian Civil War.[5] In late January 1920, Benbow was sent from Constantinople to Novorossiysk.[47] There, the ship relieved Iron Duke, and shortly thereafter rescued a group of 150 Russian soldiers and their British adviser, who had been attacked by bandits.[48] On 1 February, Rear Admiral Michael Culme-Seymour hoisted his flag aboard Benbow.[49] Shortly thereafter, men from the ship were sent to inspect White positions in the Kerch Peninsula.[50] Benbow was ordered to return to Constantinople in June, where the Mediterranean Fleet was concentrating to begin supporting Greek forces during the Greco-Turkish War; she arrived there on 19 June.[51] On 5 July, Benbow and several other vessels left Constantinople to land a force at Gemlik to secure the harbor in order to hand it over to Greek forces that would arrive later. Benbow's men returned to the ship on 16 July after a Greek battalion reached the town.[52]

In February 1921, Benbow, the battleship King George V, and several destroyers conducted training exercises in the Sea of Marmara.[53] In 1922, the ship underwent a refit at Malta. In September and October that year, she took part in further operations against Turkish forces.[5] On 1 November 1924, the 4th Squadron was renumbered as the 3rd Squadron. The 3rd Squadron was transferred to the Atlantic Fleet in March 1926 and remained there until September 1930. She became the squadron flagship on 12 May 1928, relieving Iron Duke for a major refit.[54] Benbow took part in major fleet training exercises held in March 1929 in conjunction with the Mediterranean Fleet.[55] Later that year, the ship was paid off.[56] In September 1930, Benbow was placed on the sale list.[5] Under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty, Benbow and her sisters were slated to be replaced by new construction the following year.[54] The ship was sold for scrap in January 1931 and broken up in March 1931 by Metal Industries, of Rosyth,[57] arriving there on 5 April.[58]

Footnotes

Notes

- ↑ "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

Citations

- ↑ Lecky, p. 204

- 1 2 3 4 Preston, p. 31

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 168–169, 172

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 173–174

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burt, p. 230

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 182

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 183–184

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 190

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 194–196

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 206

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 211–212

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 217

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 221

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 243

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 246

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 250

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 253

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 257–258

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 267–269

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 271

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 279–280

- ↑ Jellicoe, p. 284

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 286–287

- ↑ Marder, p. 424

- ↑ Jellicoe, pp. 288–290

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 62

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 416

- ↑ Campbell, p. 16

- ↑ Campbell, p. 37

- ↑ Campbell, p. 116

- ↑ Campbell, p. 146

- ↑ Campbell, pp. 151, 156

- ↑ Campbell, p. 210

- ↑ Campbell, p. 208

- ↑ Campbell, p. 212

- ↑ Campbell, p. 256

- ↑ Campbell, p. 262

- ↑ Campbell, p. 274

- ↑ Campbell, pp. 309–310

- ↑ Campbell, pp. 346–347, 358

- ↑ Burt, p. 215

- ↑ Massie, pp. 682–684

- ↑ Halpern (1995), pp. 418–420

- ↑ Burt, pp. 215, 218

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 143

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 137

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 145

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 153

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 154

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 251

- ↑ Halpern (2011), pp. 130, 264–266

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 304

- 1 2 Burt, p. 223

- ↑ Halpern (2011), p. 541

- ↑ Preston, p. 32

- ↑ Colledge & Warlow, p. 37

- ↑ Burt, p. 231

References

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-863-7.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Colledge, J. J. & Warlow, Ben (2010). Ships of the Royal Navy. Havertown: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61200-027-5.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Halpern, Paul, ed. (2011). The Mediterranean Fleet 1920–1929. Navy Records Society Publications. Vol. 158. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-2756-8.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company.

- Lecky, Halton Sterling (1913). The King's Ships: Together with the Important Historical Episodes Connected with the Successive Ships of the Same Name from Remote Times, and a List of Names and Services of Some Ancient War Vessels. London: H. Muirhead. OCLC 2135014.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1965). Volume II: The War Years to the eve of Jutland: 1914–1916. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow. Oxford University Press.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

Further reading

- Burt, R. A. (2012). British Battleships 1919–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-052-8.