Brilliant | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Brilliant |

| Ordered | 29 July 1756 |

| Builder | Thomas Bucknall, Plymouth Dockyard |

| Laid down | 28 August 1756 |

| Launched | 27 October 1757 |

| Completed | 20 November 1757 |

| Commissioned | October 1757 |

| Decommissioned | March 1763 |

| Out of service | 1776 |

| Honours and awards |

|

| Fate | Sold at Deptford 1 November 1776 |

| Name | Brilliant |

| Owner | Sir William James |

| Acquired | 1 November 1776 |

| In service | 1781 |

| Fate | Wrecked 1782 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Venus-class fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 70370⁄94,[2] or 704,[3] or 71838⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam |

|

| Depth of hold |

|

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Boats & landing craft carried |

|

| Complement | 240 |

| Armament | |

HMS Brilliant was a 36-gun Venus-class fifth-rate frigate of the British Royal Navy that saw active service during the Seven Years' War with France. She performed well against the French Navy in the 1760 Battle of Bishops Court and the 1761 Battle of Cape Finisterre, but was less capable when deployed for bombardment duty off enemy ports. She also captured eight French privateers and sank two more during her six years at sea. The Royal Navy decommissioned Brilliant in 1763. The Navy sold her in 1776 and she became an East Indiaman for the British East India Company (EIC). Brilliant was wrecked in August 1782 on the Comoro Islands while transporting troops to India.

Design and construction

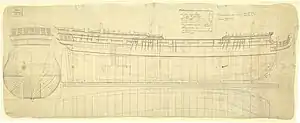

Design

Thomas Slade, the Surveyor of the Navy and former Master Shipwright at Deptford Dockyard, was the designer of the Venus-class of 36-gun frigates. Alongside their smaller cousin, the 32-gun Southampton class, the Venus-class represented an experiment in ship design; fast, medium-sized and heavily-armed, capable of overhauling smaller craft and single-handedly engaging enemy cruisers or large privateers.[5] As a further innovation, Slade borrowed from contemporary French ship design by removing the lower deck gun ports and locating the ship's cannons solely on the upper deck. This permitted the carrying of heavier ordinance without the substantial increase in hull size that would have been required to keep the lower gun ports consistently above the waterline.[6] The lower deck carried additional stores, enabling Venus-class frigates to remain at sea for longer periods without resupply.[7]

Designed in 1756 she was built by Thomas Bucknall at Plymouth Dockyard[8] and launched the following year, Venus was one of the first Royal Navy vessels to be built to a classic frigate design with a single gun deck and an emphasis on speed. Her principal role was that of a hunter of French privateers. One naval historian has described the Venus-class frigates, including Brilliant, as "the best British fighting cruisers" of their day. However they remained slightly inferior to her French equivalents in both speed and weight of ordinance.

The Admiralty approved the Venus class design on 13 July 1756 and ordered three ships.[6][lower-alpha 2][9] Brilliant was the last of these, and the only one to be constructed at Plymouth Dockyard.[9]

Construction

Thomas Bucknall, the Navy's Master Shipwright at Plymouth, oversaw the construction, which commenced with the laying of the keel on 28 August 1756. The vessel was formally named Brilliant on 17 March 1757. A 1755 Admiralty review of Plymouth Dockyard had found it inefficient, poorly staffed, and suffering from "notorious neglect,"[10] but work on Brilliant proceeded apace and she was completed by early October 1757.[9]

Crew

Her designated complement was 240 men, comprising four commissioned officers – a captain and three lieutenants – overseeing 50 warrant and petty officers, 108 naval ratings, 44 Marines, and 34 servants and other ranks.[11][lower-alpha 3] Among these other ranks were five positions reserved for widow's men – fictitious crew members whose pay was intended to be reallocated to the families of sailors who died at sea.[11][9]

Armament

Brilliant's principal armament consisted of 26 cast iron twelve-pound cannons, located along her upper deck. The guns were specifically constructed with short barrels, as traditional 12-pounder cannons were too long to fit within the frigate's narrow beam.[12] Each cannon weighed 28.5 long cwt (3,200 lb or 1,400 kg)[9] with a gun barrel length of 7 feet 6 inches (2.29 m), compared with their 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m) equivalent in larger Royal Navy vessels.[12]

The 12-pounder guns were supported by ten 6-pounder guns, eight on the quarterdeck and two on the forecastle, each weighing 16.5 long cwt (1,800 lb or 800 kg) with a barrel length of 6 feet (1.8 m).[6] Taken together, the 12-pounder and 6-pounder cannons provided a broadside weight of 189 pounds (86 kg).[1] She was also equipped with twelve ½-pounder swivel guns for anti-personnel use.[9] These swivel guns were mounted in fixed positions on the quarterdeck and forecastle.[12]

Royal Navy service

Privateer hunter

Brilliant was commissioned in October 1757 under the command of post-captain Hyde Parker and entering Navy service during the early stages of the Seven Years' War against France.[9][1]

Her first engagement was on 19 December 1757 when, in company with the 28-gun HMS Coventry, she encountered the French privateer Diamond. A contemporary report described the Quebec-built Diamond as "a very fine vessel" of 200 tons burthen, carrying 14 carriage guns and a cargo of furs. Diamond opened fire on Brilliant as she approached, but before the British could retaliate the French vessel exploded and sank. The detonation was assumed to have been caused by sparks flying back from the privateer's guns and igniting her powder magazine. Only 24 of Diamond's 70 crew survived the explosion. These men were hauled aboard Brilliant and Coventry as prisoners of war.[13]

On 24 December Brilliant and Coventry encountered their second privateer, the 24-gun Le Dragon. There was a brief exchange of fire in which four French sailors were killed and up to 12 wounded, against six wounded men aboard Coventry. After the outgunned French vessel struck her colours the British took her surviving 280 crew prisoner. On the following day a third French ship hove into view, the Intrepid, a 14-gun snow-rigged privateer. After a short chase she fell within range of Brilliant's guns; the French fired first, wounding one British sailor. The responding broadside from Brilliant capsized Intrepid and killed ten men among her crew of 120. The survivors were taken prisoner aboard Brilliant and handed over to British authorities at Plymouth.[13]

In March 1758 Brilliant alone captured two more French vessels, the 20-gun privateer Le Nymphe and the 12-gun Le Vengeur.[1][14] On 8 April these two captured vessels were sailed to Plymouth.[14]

Coastal raids

In late 1758 Brilliant joined a Royal Navy squadron supporting amphibious raids along the French coastline. In company with other frigates she protected fleet transports and bomb vessels and assisted with shore bombardment in the Battle of Saint Cast on 11 September 1758.[9][15] The progenitor of the Royal Geographic Society, James Rennell, was a midshipman aboard Brilliant during this period and produced his first coastal map while the frigate was stationed off Saint Cast.[15] Brilliant played an undistinguished role in this engagement as her draught was too deep for her to approach the shore. By the afternoon of the battle she was close enough to the beach for her crew to witness the surrounding and defeat of the British Grenadier Guards, but was too distant to range her guns onto their French assailants.[15]

Brilliant resumed her privateer hunting in the spring of 1759. On 17 April she encountered and forced the surrender of the 22-gun French vessel Basque around 700 miles (1,100 km) west of Cape Clear. As with previous privateer captures, the captured French ship and her crew were taken to Plymouth and handed over to Navy authorities.[16]

Captain Parker left Brilliant in 1759, having been promoted to the captaincy of the 74-gun HMS Norfolk.[17] Command of Brilliant temporarily transferred to Captain John Lendrick, with the frigate assigned to a squadron under Admiral George Rodney for a coastal raid on Le Havre.[9] The raid took place on 3 July with Brilliant acting to protect the squadron's bomb vessels and transport ships from some distance offshore.[15] Lendrick was subsequently replaced by James Logie, who remained with Brilliant until she was decommissioned in 1763.[1]

Battle of Bishops Court

The Battle of Bishops Court was a shift in Brilliant's focus from capturing French privateers to direct engagement with an enemy naval squadron. Between 21 and 26 February 1760 a force of three French vessels, the 44-gun Maréchal de Belle-Isle, the 36-gun Blonde and the 30-gun Terpsichore, arrived off the coast of Ireland.[18] Under the command of privateer François Thurot, they landed 600 French troops and captured the town of Carrickfergus.[19] Thurot held the town for five days.[20]

Brilliant and her sister ship HMS Pallas were in port at Kinsale in southern Ireland,[lower-alpha 4] and were sent north to intercept Thurot's force.[20] While at sea they were joined by HMS Aeolus whose captain, John Elliott, assumed overall command of the squadron.[22] The three Royal Navy frigates reached Dublin on the morning of 26 February but bad weather prevented them from entering Belfast Lough. On the same day, Thurot re-embarked his troops and put to sea, evading the British vessels and seeking to return south to France.[23]

After two days of searching, the three Royal Navy frigates encountered Thurot's forces at 4 a.m. on 28 February between the Mull of Galloway and the Isle of Man.[24] A general chase ensued with Brilliant overhauling the 36-gun Blonde and engaging her in battle at around 9 a.m., off shore from Bishopscourt, Isle of Man.[25] Blonde quickly surrendered, as did Terpsichore which had been fired upon by Pallas. Thurot's flagship Maréchal de Belle-Isle fought on alone against all three Royal Navy vessels, with her crew making repeated attempts to board and seize Aeolus. After ninety minutes of close combat Thurot was killed by a shot through the neck, and Maréchal de Belle-Isle was so battered from cannon fire that she began to sink.[23] Her surviving crew surrendered and were taken prisoner. Brilliant, Pallas and Aeolus then anchored off the Isle of Man to repair damage to their rigging and masts before sailing for Portsmouth with their prizes.[24][26]

The French had suffered 300 casualties in the battle.[27] A further 1000 men were taken prisoner, including both soldiers and crew. British casualties were small with Aeolus suffering four killed and 15 wounded; Pallas one killed and five wounded and Brilliant escaping with no deaths and 11 men wounded.[24]

Battle of Cape Finisterre

On 14 August 1761, Brilliant was accompanying the 74-gun HMS Bellona from Lisbon to England when they encountered Courageux, a 74-gun French ship of the line, and two frigates, Malicieuse and Hermione. After some maneuvering the British and French squadrons finally engaged with each other at 6.00 a.m. on the morning of 14 August off shore from Cape Finisterre.[28]

Bellona opened fire on Corageux while Brilliant engaged Maliceuse and Hermione. Through skillful sailing, Logie was able to keep both French frigates at bay and unable to assist Courageux, which surrendered to Bellona after ninety minutes of fighting. At 7.30 a.m. Maliceuse and Hermione made sail and retreated, with Brilliant too damaged to give chase. British losses in the battle numbered six killed and 28 wounded on Bellona and five killed and 16 wounded on Brilliant. On the French side, losses on Courageux alone were 240 killed and 110 wounded.[28] Historian William Laird Clowes has suggested that the much higher French casualty rate was the result of differences in tactics. The French gun crews trained to fire at the masts and rigging of an enemy ship in order to disable it ahead of a boarding attempt. By contrast, British crews were trained to fire into the hulls of enemy ships.[29]

Later service

There were several small victories for Brilliant throughout 1761, with the capture of the 6-gun privateers Le Malouin and Le Curieux from St. Malo, and the 8-gun La Mignonne from Bayonne.[9] After a period spent refitting at Portsmouth, in January 1763 Brilliant was sailed to Dublin to assist in clearing stores and transporting crew from the 66-gun HMS Devonshire, which was in port after being damaged at sea.[30] Later that year she had her final victory at sea, overhauling and forcing the surrender of the small 8-gun privateer L'Esperance.[9]

War with France was by now drawing to a close, and in March 1763 Logie brought Brilliant to Deptford Dockyard where she was decommissioned and her crew paid off to join other vessels.[1]

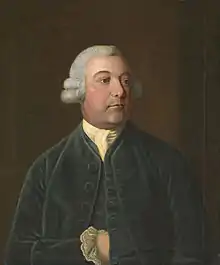

East India Company and loss

Brilliant remained at Deptford until 1776 when the Navy offered her for sale as surplus to Navy requirements. Sir William James purchased her on 1 November 1776 for the sum of £800.[1][31] He retained her name and converted her into an East Indiaman in 1781. Captain Charles Mears sailed Brilliant on 5 May 1782 from Portsmouth for India, where she was to remain.[3]

Her career in private hands was short-lived. She narrowly avoided disaster on 26 January 1782 when she struck and heavily damaged HMS Albemarle, under the command of Captain Horatio Nelson, which was anchored off the Kentish coast.[32][33]

On 5 May 1782, Captain Charles Mears sailed Brilliant from Portsmouth, bound to India with troops, and to remain there. On 28 August she struck a rock off Johanna in the Comoro Islands and was lost.[3] The majority of the crew survived the wreck but more than 100 soldiers and three officers from the 15th Hanoverian Regiment drowned.[34][2]

Legacy

Naval historian William Clowes described the Venus-class frigates, including Brilliant, as "the best British fighting cruisers of the days before the accession of George III."[35] Even so, they were slower than their French counterparts, having been built of much heavier timbers and with less flexible joints. This proved to be a substantial defect for a vessel designed for the chase; in 1759 Royal Navy captain William Hotham described a captured French frigate of equivalent size as having "quite the advantage on the Aeolus or Brilliant" in speed and maneuvreability.[36] Admiralty generally regarded Brilliant and her sister ships as superior only as convoy escorts and in short-range engagements.[37]

The Admiralty Board also considered Brilliant too lightly armed for her size. She measured an additional 50 tons burthen over a standard 32-gun frigate but carried only four more cannon.[35][37] For these reasons, Brilliant was the last vessel to be built in the Venus-class. Subsequent generations of Royal Navy frigates preserved elements of her design, but with an extended hull to allow for additional gun ports and the carrying of larger weapons including the 18-pounder long gun.[7]

Notes

- ↑ A Navy Board letter of 19 June 1765 describes Venus-class frigates as carrying a cutter instead of a yawl.[4]

- ↑ Other Venus class vessels were HMS Pallas and HMS Venus.

- ↑ The 34 servants and other ranks provided for in the ship's complement consisted of 23 personal servants and clerical staff, five assistant carpenters, an assistant sailmaker, and five widow's men. Unlike naval ratings, servants and other ranks took no part in the sailing or handling of the ship.[11]

- ↑ Brilliant had damaged her foremast in a storm and had made port in Kinsale for repairs.[21]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "British Fifth Rate frigate 'Brilliant' (1757)". threedecks.org. 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- 1 2 Hackman (2001), p. 71.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 British Library: Brilliant

- 1 2 Gardiner (1992), pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Clowes (1898), p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Winfield (2007), pp. 189–191.

- 1 2 Lyon (1993), p. 62.

- ↑ "Thomas Bucknall".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Winfield (2007), pp. 191–193.

- ↑ Admiralty Minutes, 27 February 1755. Cited in Middleton 1988, p. 111

- 1 2 3 Rodger (1986), pp. 348–351.

- 1 2 3 Gardiner (1992), p. 81.

- 1 2 "No. 9755". The London Gazette. 7 January 1758. p. 2.

- 1 2 "Tuesday's Post". Leeds Intelligencer. Griffith White. 11 April 1758. p. 2. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Rodd, Rennell (April 1930). "Major James Rennell". The Geographical Journal. The Royal Geographical Society. 75 (4): 290. JSTOR 1784813.

- ↑ "Admiralty Office, May 11". Derby Mercury. Derby, UK: S. Drewry. 11 May 1759. p. 3.

- ↑ Winfield (2007), p. 58.

- ↑ Harrison (1873), pp. 67–70.

- ↑ McLynn (2011), p. 385.

- 1 2 McLeod (2012), pp. 161–64.

- ↑ "From on board the Aelous, lying in Ramsey Road, Isle of Man, 28 February 1760". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 22 March 1760. p. 3. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Laughton. "Elliot, John (1732–1808)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "Edinburgh: Extract of a Letter from London". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 3 March 1760. p. 2. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Dublin". The Dublin Courier. Dublin: James Potts. 3 March 1760. p. 1. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ Harrison (1873), p. 71.

- ↑ "Country News". The Derby Mercury. Edinburgh: S. Drewry. 28 March 1760. p. 2. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Robson (2016), pp. 145–146.

- 1 2 "No. 10136". The London Gazette. 1 September 1761. p. 2.

- ↑ Clowes (1898), p. 307.

- ↑ "Dublin". The Dublin Courier. Dublin: James Potts. 28 January 1763. p. 2. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ Cordani, Andrea. "Brilliant ID 861". East India Company Ships. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ↑ Goodwin (2002), p. 102.

- ↑ Knight (2005), p. 564.

- ↑ "London, April 8". Manchester Mercury. Joseph Harrop. 15 April 1783. p. 1. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- 1 2 Clowes (1898), pp. 7–8.

- ↑ McLeod, Anne Byrne. The Mid-Eighteenth Century Navy from the Perspective of Captain Thomas Burnett and His Peers (Thesis). University of Exeter. pp. 116–118. OCLC 757128667.

- 1 2 Gardiner, Robert (1975). "The First English Frigates". The Mariner's Mirror. 61 (2): 168. doi:10.1080/00253359.1975.10658020.

References

- Clowes, William Laird (1898). The Royal Navy: A History From the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 3. London: Sampson, Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 645627800.

- Gardiner, Robert (1992). The First Frigates. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0851776019.

- Goodwin, Peter (2002). Nelson's Ships: A History of The Vessels In Which He Served: 1771–1805. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0811710076.

- Hackman, Rowan (2001). Ships of the East India Company. Gravesend: World Ship Society. ISBN 0905617967.

- Knight, Roger (2005). The Pursuit of Victory : The Life and Achievement of Horatio Nelson. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 046503764X.

- Lyon, David (1993). The Sailing Navy List. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0851776175.

- McLeod, A. B (2012). British Naval Captains of the Seven Years' War: The View from the Quarterdeck. New York: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843837510.

- McLynn, Frank (2011). 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 9781446449271.

- Middleton, Richard (1988). "Naval administration in the age of Pitt and Anson, 1755–1763". In Black, Jeremy; Woodfine, Philip (eds.). The British Navy and the Use of Naval Power in the Eighteenth Century. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0718513088.

- Robson, Martin (2016). A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War. London: I.B. Taurus. ISBN 9781780765457.

- Rodger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870219871.

- Harrison, William, ed. (1873). Mona Miscellany: A Selection of Proverbs, Sayings, Ballads, Customs, Superstitions and Legends Peculiar to the Isle of Man. Isle of Man: The Manx Society. OCLC 729306735.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714 to 1792. London: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1844157006.