HMS Calypso | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Calypso |

| Builder | HM Dockyard Chatham |

| Cost | Hull: £82,000; machinery: £37,500[1] |

| Laid down | 1881 |

| Launched | 7 June 1883 |

| Commissioned | 21 September 1885 (first commission) |

| Renamed | HMS Briton, 15 February 1916 |

| Reclassified | Training ship, 2 September 1902 |

| Fate | Sold 7 April 1922; burned off Jobs Cove near Embree, NL |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Calypso-class corvette |

| Displacement | 2,770 long tons (2,810 t) |

| Length | 235 ft (71.6 m) pp |

| Beam | 44 ft 6 in (13.6 m) |

| Draught | 19 ft 11 in (6.1 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4-cylinder J. and G. Rennie compound-expansion steam engine driving a single screw |

| Sail plan | Barque rig[Note 1] |

| Speed | 13.75 knots (25.47 km/h; 15.82 mph) powered; 14.75 knots (27.32 km/h; 16.97 mph) forced draught |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | Deck: 1.5 in (38 mm) over machinery |

HMS Calypso was a corvette (designated as a third-class cruiser from 1887[2]) of the Royal Navy and the lead ship of its namesake class. Built for distant cruising in the heyday of the British Empire, the vessel served as a warship and training vessel until 1922, when it was sold.

Originally classified as a screw corvette,[Note 2] Calypso was also one of the Royal Navy's last sailing corvettes but supplemented an extensive sail rig with a powerful engine. Among the first of the smaller cruisers to be given steel hulls instead of iron, the hull nevertheless was cased with timber and coppered below the water line, as were wooden ships.[3]

Unlike Calliope, the more famous member of the class, Calypso had a quiet career, consisting mainly of training cruises in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1902 the warship was sent to the colony of Newfoundland and served as a training ship for the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve before and during the First World War. In 1922 Calypso was declared surplus and sold, then used as a storage hulk. Its hull still exists, awash in the Bay of Exploits south of Embree in Newfoundland.

Design

Calypso and Calliope comprised the Calypso class of corvettes, designed by Nathaniel Barnaby. Part of a long line of cruiser classes built for protecting trade routes and colonial police work,[4] they were the last two sailing corvettes built for the Royal Navy. Corvettes had been built of iron since the Volage class of 1867, but the Calypsos and the preceding Comus class used steel. Corvettes were designed to operate across the vast distances of Britain's maritime empire, and could not rely on dry docks for maintenance. Since iron (and steel) hulls were subject to biofouling and could not easily be cleaned, the established practice of copper sheathing was extended to protect them; the metal plating of the hull was timber-cased and coppered below the waterline.[3]

The Calypsos differed from the ships of the preceding Comus class in armament, including new 6-inch rifles in place of the 7-inch muzzleloaders and 64-pounders that originally armed the first ships of the parent class. Although similar in general appearance to their predecessors, the Calypsos had guns sponsoned out both fore and aft and had no gunports under the quarterdeck and foredeck. They were also slightly longer, had a deeper draught, and displaced 390 tons more.[5] Calypso's engine produced were of 4,023 indicated horsepower, over 50 per cent more powerful than those of its nine half-sisters, which yielded one more knot of speed.[5] This compound-expansion engine could drive Calypso at 13¾ knots, or 14¾ knots with forced draught.[6]

The vessel nevertheless carried a barque rig of sail on three masts,[Note 1] including a full set of studding sails on fore and mainmast.[7] This rig enabled the corvette to serve in areas where coaling stations were rare, and to rely entirely on sails for propulsion. The class was well-suited to its designed role: trade protection and distant cruising service for the British Empire at its Victorian peak.[6]

Service with the fleet

While the class was designed for long-range protection of the trade routes of the empire,[8] and Calypso participated in war games, much of its career was spent in activities appropriate to an empire at peace. The ship served in home waters and participated in fleet exercises, including a simulated attack on Britain,[9] and visited Kiel,[10] site of a major base of the Imperial German Navy often visited by British vessels. In 1890, Britain gave up the isle of Heligoland in the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty, and Calypso was assigned to carry out the ceremony of transfer to the German Empire and bring back the island's last British governor.[11]

From the time of first commission in 1885 until was placed in reserve in 1898, Calypso was part of the Sail Training Squadron, the "last refuge of the sailing navy" apart from a handful of smaller vessels.[12][13] The warship made cruises to the West Indies,[14] the Canary Islands, and Norway.[15] In 1895 Calypso was part of the squadron which conducted surveys well above the Arctic Circle, and a landfall and cluster of buildings on Svalbard, Norway, now a cultural heritage site, were named in honour of its visits to those waters.[16] On other occasions it assisted in the salvage of a civilian ship, for which its officers and crew were awarded salvage money,[17] and passed on hydrographic information from waters near Iceland.[18]

On 26 June 1897 Calypso was present at the Review of the Fleet off Spithead held to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria's accession to the throne.[19] Paid off into reserve at Devonport in 1898,[12] it was no longer considered a fighting ship by the turn of the century, and it was felt it could best be employed in training naval reservists for service at sea.[20]

Training ship

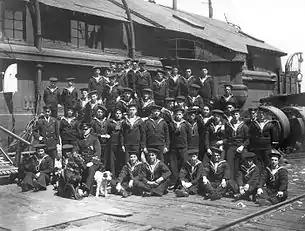

On 3 September 1902 Calypso was placed back into commission under the command of Commander Frederick Murray Walker,[12][21] and was sent across the Atlantic to become a training ship for the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve (RNR), which trained men for service in the Royal Navy.[22][23] The Reserve had been founded in 1900 as an experiment to assist the Admiralty in the manning of ships, and to enable the Newfoundlanders to assist in the defence of the empire, training their seafarers in the winter months when the fishery was not worked.[24] As the result of this trial, the Admiralty agreed to provide a vessel, and the colony agreed to pay for the refit, as well as an annual subvention to support the training programme.[24]

The location of the vessel was controversial, and the community of Argentia was proffered as a substitute for the colonial capital of St. John's. Reasons for this proposal included both a desire to protect the larger city from the conjectured debaucheries of sailors, and conversely to protect the reservists, many of whom were married, from the temptations (including prostitution) which might be available in the city.[25] In a time of tensions between Britain and France, Argentia also had the benefit of being closer to the French territory of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and it was thought beneficial to have a British military force in proximity to the French territory in the event of a dispute.[26] These objections were felt to be outweighed by cost, convenience, and accessibility of staff to the colonial government, and St. John's was chosen to host the ship.

Calypso arrived at St. John's on 15 October 1902.[27] The vessel was hulked;[28] the masts were removed, as was the funnel from the boilers, and a drill hall was erected on the weather deck. Without sail or working boilers the vessel could no longer go to sea and was permanently moored wharfside at the western end of the St. John's harbour.[28]

Prior to the outbreak of war candidates had to be fishermen or sailors, and the RNR maintained a reserve strength of 500–600 men.[29] By 1914, over 1,400 seamen had been trained, and more than 400 answered the call to arms on the outbreak of the Great War.[30] The Reserve provided crew for ships of the Royal Navy,[29] including over 100 seamen taken aboard HMCS Niobe a month after the start of the war, the first group of Newfoundlanders to go to war.[30] It also provided home defence,[29] including manning coast artillery at the entrance to the St. Johns harbour,[31] and the protection of Newfoundland's shore and shipping.[32] Calypso and a small, slow armed patrol vessel were the colony's only warships,[23] and Calypso could not go to sea.

In 1916, Calypso was renamed HMS Briton, and the former name was given to a new light cruiser laid down in that year, which entered service in 1917.[33]

Before the war the owner of the dock where Calypso was berthed had sought the vessel's removal. The matter was held in abeyance during the war years, but after the conclusion of hostilities the subject arose anew. Relocation would have been a significant expense to the Admiralty, and the Colonial Office was informed that the dominion would accept complete withdrawal of the vessel. By 1922 naval estimates were being slashed and the Washington Naval Treaty limited the size of fleets.[34] The Admiralty therefore summarily discontinued the Newfoundland RNR, and there being no further need of the ship, Briton was made available for disposition.[35]

Later use, and legacy

Briton was sold in 1922 and was used in St. John's for the storage of salt.[36][37] In 1952 the hulk was moved to Lewisporte harbour.[38] Some thought was given to preservation,[38] but in 1968 it was towed to a coastal bay near Embree, and burned to the waterline.[39] The hull still is there, awash in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean.[Note 3] The cruiser's anchor sits outside a local inn,[39] and other artefacts are in museums.[40]

A 12lb deck gun was removed in 1965 and taken to the Royal Canadian Legion Branch #12 in Grand Falls, Newfoundland and was positioned on the front of the Legion building. A 12lb shell that was removed from that same gun in 1965 as well as a 5" shell from Calypso was turned over to the RCMP for disposal as it has been suspected to still be live. Those two shells from the Calypso sat on a shelf in the Branch 12 Military Museum for over 35 years in plain view and accessible to everyone. (From the Historical Committee, Royal Canadian Legion, Grand Falls Branch #12, NL)

These remnants are not the sole remaining legacy. Calypso, created as a ship of war, has given its name another training institution, but one with peaceful purposes. Inspired by the traditions of the ship where Newfoundlanders once trained to be competent and able seamen for the Royal Navy, the Calypso Foundation of Lewisporte trains developmentally disabled individuals to become productive workers and live independently.[41] This charitable foundation carries on the name of HMS Calypso.[42]

In the final chapter of James Joyce's 1922 novel Ulysses, Molly Bloom recalls having had a brief affair with a sailor from Calypso in Gibraltar circa 1886.[43]

Notes

- 1 2 Published sources state the class had barque rigs, Paine (2000), vol. 799, p. 29, which is shown in some images. Other drawings and photographs show a ship rig, with yards and square sails on the mizzenmast. Archibald (1970), p. 49; J.S. Virtue & Co., lithograph of HMS "Calliope", 3rd Class Cruiser Archived 2011-06-08 at the Wayback Machine See Commons images and photographs linked below.

- ↑ A screw corvette was a propeller-driven small cruiser.

- ↑ More precisely, the hull lies in Jobs Cove, off Burnt Bay (an arm of Notre Dame Bay) on the north coast of Newfoundland. Calypso is the larger and more northerly of the two hulls shown. An image is here (the hull on the left is that of Calypso).

References

- 1 2 Winfield (2004), p.273

- ↑ Winfield (2004), p.265

- 1 2 Archibald (1971), p. 43.

- ↑ Lyon (1980), pp. 21–22, 35–40.

- 1 2 Archibald (1971), p. 49.

- 1 2 Navy Historical Center, HMS Calliope (1884-1951).

- ↑ Harland, John H. (1985), Seamanship in the Age of Sail, p. 172. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis. ISBN 0-87021-955-3.

- ↑ Paine (2000), p. 29.

- ↑ Tryon's Brilliant Tactics, The New York Times (2 July 1893), p. 16.

- ↑ Dodd, Francis (1917), Admirals of the British Navy (1917–1918), Chapter X.

- ↑ Hertslet, Edward (1891), The Map of Europe by Treaty, vol. IV, pp. 3288–89. Harrison and Sons, for HM Stationery Office.

- 1 2 3 Osbon (1964), p. 207.

- ↑ Archibald (1971), p. 42.

- ↑ Hansard, House of Commons Debate, 24 May 1886, vol. 35 cc 1834–35 (question to Secretary to the Admiralty on breakdown of machinery while with training squadron on cruise to West Indies)

- ↑ Papers of Vice Admiral A C Scott, Archives, Imperial War Museum.

- ↑ Johansen, Bjørn Fossli (ed.); Henriksen, Jørn; Overreinand, Øystein; and Prestvold, Kristin; Calypsobyen, Cruise Handbook for Svalbard, Norwegian Polar Institute (May 2009). The site lies within South Spitsbergen National Park.

- ↑ The London Gazette, 6 October 1891, p. 5231 and 11 December 1891, p. 6846.

- ↑ The London Gazette, 4 Sept 1896, p. 4991.

- ↑ The London Gazette Extraordinary, 14 March 1898, pp. 1616, 1621.

- ↑ Hunter, p. 39.

- ↑ "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36861. London. 1 September 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ "Newfoundland", entry in Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events (1902), Volume 6, p. 384.

- 1 2 Jane, p. 100.

- 1 2 Hunter, p. 36.

- ↑ Hunter, passim.

- ↑ Hunter, p. 41. The discussion on location took place only a few years after the Fashoda Incident in 1898 when the two nations came close to war, before Imperial Germany supplanted France as Britain's principal rival and before the Anglo-French Entente of 1904, which resolved colonial difficulties.

- ↑ "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36901. London. 17 October 1902. p. 8.

- 1 2 Hunter, pp. 39, 44–45.

- 1 2 3 Hillier.

- 1 2 Parsons, p. 147.

- ↑ Maple Leaf, p.10 Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ HMS Calypso fonds.

- ↑ Jane, p. 57.

- ↑ Hunter, pp. 47–52.

- ↑ Hadley, p. 255.

- ↑ Colledge (2006), p. 57.

- ↑ Guide to the business collections of A.H. Murray and Company, Maritime History Archive. Briton Series 7.0 HMS Briton

- 1 2 Osbon (1963), p. 208.

- 1 2 Lewisporte.

- ↑ Exhibits: The H.M.S. Calypso/Briton, Admiralty House Museum & Archives. Room housing original artefacts.

- ↑ "Community Profits", Social Enterprise in Newfoundland and Labrador (2008). p. 38; Calypso Foundation - Work Oriented Rehabilitation Centre (WORC), Community Services Council, Newfoundland and Labrador (October 2001).

- ↑ Extension Service, Memorial University of Newfoundland (1978), Calypso (video), beginning at 53 seconds into 18-minute video.

- ↑ Joyce, James (1986). Gabler, Hans Walter (ed.). Ulysses: The Corrected Text. Random House. p. 626. ISBN 0-394-55373-X.

Principal sources

- Archibald, E.H.H. (1971). The Metal Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy 1860-1970. Ray Woodward (ill.). New York: Arco Publishing Co. ISBN 0-668-02509-3.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Hadley, Michael L.; Hubert, Robert Neal; & Crickard, Fred W. (1992). A Nation's Navy: In Quest of Canadian Naval Identity. McGill–Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-1506-2.

- Hillier, David (September 2004). "Royal Naval Reserve". Newfoundland and the Great War. Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- HMS Calypso fonds, summary of records of the vessel, including records of construction and RN service, obtained from A.H. Murray & Co., owner from 1922 to 1952. Maintained by Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Hunter, Mark C. "HMS Calypso: Locating the Newfoundland Royal Naval reserve drill ship, 1900-22". The Great Circle: Journal of the Australian Association for Maritime History, 28:1 (2006), 36–60. ISSN 0156-8698.

- Jane, Fred T. (1990). Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I. London: Studio Editions. ISBN 1-85170-378-0. Facsimile of 1919 edition Of Janes’s Fighting Ships published by Jane's Publishing Company, supplemented by entries from 1914 edition.

- Lewisporte, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Division of Extension Services, Decks Awash, Vo. 15, No. 3 (May–June 1986), republished by CanadaGenWeb.org. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- The Maple Leaf (5 March 2008), Vol. 11, No. 9. Canadian Forces. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Osbon, G. A. (1963). "Passing of the steam and sail corvette: the Comus and Calliope classes". Mariner's Mirror. London: Society for Nautical Research. 49: 193–208. doi:10.1080/00253359.1963.10657732. ISSN 0025-3359.

- Paine, Lincoln P. (2000). Warships of the World to 1900. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-98414-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help).

- Parsons, W. David (2003), "Newfoundland and the Great War", published in Canada and the Great War: Western Front Association Papers. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2546-7.

- Winfield, R.; Lyon, D. (2004). The Sail and Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-032-6. OCLC 52620555.

External links

- The Last Wooden British Warship; HMS Calypso/Briton, HiddenNewfoundland.ca. Well-illustrated website with newer photographs and information about Calypso.

- Black and white drawing, port bow 1/4 view, spectacular view of vessel under full sail including stunsails; appears to show ship rig.

- Photograph, port broadside view, no sails set, yards on mizzen. Boat alongside; vessel appears to be at anchor.

- Links to photographs showing Calypso/Briton while in Newfoundland, including personnel, and erection on deck.