HMS Indefatigable | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Indefatigable |

| Ordered | 1908–1909 Naval Programme |

| Builder | HM Dockyard, Devonport |

| Laid down | 23 February 1909 |

| Launched | 28 October 1909 |

| Commissioned | 24 February 1911 |

| Fate | Sunk during the Battle of Jutland, 31 May 1916 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Indefatigable-class battlecruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 590 ft (179.8 m) |

| Beam | 80 ft (24.4 m) |

| Draught | 29 ft 9 in (9.07 m) (deep load) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) |

| Range | 6,690 nmi (12,390 km; 7,700 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 800 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

HMS Indefatigable was the lead ship of her class of three battlecruisers built for the Royal Navy during the first decade of the 20th Century. When the First World War began, Indefatigable was serving with the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron (BCS) in the Mediterranean, where she unsuccessfully pursued the battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau of the German Imperial Navy as they fled toward the Ottoman Empire. The ship bombarded Ottoman fortifications defending the Dardanelles on 3 November 1914, then, following a refit in Malta, returned to the United Kingdom in February where she rejoined the 2nd BCS.

Indefatigable was sunk on 31 May 1916 during the Battle of Jutland, the largest naval battle of the war. Part of Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty's Battlecruiser Fleet, she was hit several times in the first minutes of the "Run to the South", the opening phase of the battlecruiser action. Shells from the German battlecruiser Von der Tann caused an explosion ripping a hole in her hull, and a second explosion hurled large pieces of the ship 200 feet (60 m) in the air. Only three of the crew of 1,019 survived.

Design and description

No battlecruisers were ordered after the three Invincible class ships in 1905 until Indefatigable became the lone battlecruiser of the 1908–1909 Naval Programme. A new Liberal Government had taken power in January 1906 and demanded reductions in naval spending, and the Admiralty submitted a reduced programme, requesting dreadnoughts but no battlecruisers. The Cabinet rejected this proposal in favour of two outmoded armoured cruisers but finally acceded to a request for one battlecruiser instead, after the Admiralty pointed out the need to match the recently published German naval construction plan and to maintain the heavy gun and armour industries. Indefatigable's outline design was prepared in March 1908, and the final design, slightly larger than Invincible with a revised protection arrangement and additional length amidships to allow her two middle turrets to fire on either broadside, was approved in November 1908. A larger design with more armour and better underwater protection was rejected as too expensive.[1]

.jpg.webp)

Indefatigable had an overall length of 590 feet (179.8 m), a beam of 80 feet (24.4 m), and a draught of 29 feet 9 inches (9.1 m) at deep load. The ship normally displaced 18,500 long tons (18,800 t) and 22,130 long tons (22,490 t) at deep load. She had a crew of 737 officers and ratings.[2]

The ship was powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each driving two propeller shafts, using steam provided by 31 coal-burning Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The turbines were rated at 43,000 shaft horsepower (32,000 kW) and were intended to give the ship a maximum speed of 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph). During her sea trials on 10 April 1911, Indefatigable reached a top speed of 26.89 knots (49.8 km/h; 30.9 mph) from 55,140 shp (41,120 kW) after her propellers were replaced.[3] She carried enough coal and fuel oil to give her a range of 6,330 nautical miles (11,720 km; 7,280 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4]

The Indefatigable class had a main armament of eight breech-loading BL 12-inch (305 mm) Mark X guns mounted in four hydraulically powered twin-gun turrets. Two turrets were mounted fore and aft on the centreline, identified as 'A' and 'X' respectively. The other two were wing turrets mounted amidships and staggered diagonally: 'P' was forward and to port of the centre funnel, while 'Q' was situated starboard and aft. 'P' and 'Q' turrets had some limited ability to fire to the opposite side. Their secondary armament consisted of sixteen BL 4-inch (102 mm) Mark VII guns positioned in the superstructure.[5] They mounted two 17.72-inch (450 mm) submerged torpedo tubes, one on each side aft of 'X' barbette, and twelve torpedoes were carried.[6]

The Indefatigables were protected by a waterline 4–6-inch (102–152 mm) armoured belt that extended between and covered the end barbettes. Their armoured deck ranged in thickness between 1.5 and 2.5 inches (38 and 64 mm) with the thickest portions protecting the steering gear in the stern. The turret faces were 7 inches (178 mm) thick, and the turrets were supported by barbettes of the same thickness.[7]

Indefatigable was unique among British battlecruisers in having an armoured spotting and signal tower behind the conning tower, protected by 4 inches (102 mm) of armour. However, the spotting tower was of limited use, as its view was obscured by the conning tower in front of it and the legs of the foremast and superstructure behind it.[8] During a pre-war refit, a 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinder was added to the rear of the 'A' turret roof, and this turret was equipped to control the entire main armament as an emergency backup for the normal fire-control positions.[9]

Wartime modifications

Indefatigable received a single QF 3-inch 20 cwt[Note 1] anti-aircraft gun on a high-angle Mark II mount in March 1915. It was provided with 500 rounds. All of her 4-inch guns were enclosed in casemates and given gun shields during a refit in November 1915 to better protect the gun crews from weather and enemy action, although two aft guns were removed at the same time.[10]

She received a fire-control director between mid-1915 and May 1916 that centralised fire control under the director officer who now fired the guns. The turret crewmen merely had to follow pointers transmitted from the director to align their guns on the target. This greatly increased accuracy since the ship's roll no longer dispersed the shells as each turret fired on its own; also, the fire-control director could more easily spot the fall of the shells.[11]

Service

.jpg.webp)

Early career

Indefatigable was laid down at the Devonport Dockyard, Plymouth on 23 February 1909. She was launched on 28 October 1909 and was completed on 24 February 1911.[12] Upon commissioning, Indefatigable served in the 1st Cruiser Squadron, which in January 1913 was renamed the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron (BCS). C. F. Sowerby was appointed captain on 24 February 1913.[13] In December of the same year, she transferred to the Mediterranean, where she joined the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron.[14]

Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau

Indefatigable, accompanied by the battlecruiser Indomitable and under the command of Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne, encountered the German battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau on the morning of 4 August 1914, which were headed east after a cursory bombardment of the French Algerian port of Philippeville. Britain and Germany were not yet at war, so Milne turned to shadow the Germans as they headed back to Messina to re-coal. All three battlecruisers had problems with their boilers, but Goeben and Breslau were able to break contact and reached Messina by the morning of the 5th. By this time, Germany had invaded Belgium and war had been declared, but an Admiralty order to respect Italian neutrality and stay more than 6 nautical miles (11 km) from the Italian coast precluded entering the Strait of Messina, from which they could have observed the port directly. Therefore, Milne stationed Inflexible and Indefatigable at the northern exit of the strait, expecting the Germans to break out to the west where they could attack French troop transports. He stationed the light cruiser Gloucester at the southern exit, and sent Indomitable to coal at Bizerte, where she was ready for action in the Western Mediterranean.[15]

The Germans sortied from Messina on 6 August and headed east, toward Constantinople, trailed by Gloucester. Milne, still expecting Rear-Admiral Wilhelm Souchon to turn west, kept the battlecruisers at Malta until shortly after midnight on 8 August when he set sail at a leisurely 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) for Cape Matapan, where Goeben had been spotted eight hours earlier. At 14:30,[Note 2] he received an incorrect message from the Admiralty stating that Britain was at war with Austria-Hungary. War would not actually be declared until 12 August, and the order was countermanded four hours later, but Milne gave up the hunt for Goeben, following his standing orders to guard the Adriatic against an Austrian break-out attempt. On 9 August, Milne was given clear orders to "chase Goeben which had passed Cape Matapan on the 7th steering north-east."[16] Milne still did not believe that Souchon was heading for the Dardanelles, and so he resolved to guard the exit from the Aegean, unaware that the Goeben did not intend to come out.[16]

On 3 November 1914, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, ordered the first British attack on the Dardanelles following the commencement of hostilities between Ottoman Turkey and Russia. The attack was carried out by Indomitable and Indefatigable, as well as the French pre-dreadnought battleships Suffren and Vérité. The intention of the attack was to test the fortifications and measure the Turkish response. The results were deceptively encouraging. In a twenty-minute bombardment, a single shell struck the magazine of the fort at Sedd el Bahr at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula, displacing (but not destroying) 10 guns and killing 86 Turkish soldiers. The most significant consequence was that the attention of the Turks was drawn to strengthening their defences, and they set about expanding the mine field.[17] This attack actually took place before Britain's formal declaration of war against the Ottoman Empire on 6 November. Indefatigable remained in the Mediterranean until she was relieved by Inflexible on 24 January 1915 and proceeded to Malta for a refit; she then sailed to England on 14 February and joined the 2nd BCS upon her arrival. The ship conducted uneventful patrols of the North Sea for the next year and a half. She was the temporary flagship of the 2nd BCS during April–May 1916, while her half-sister HMAS Australia was under repair after colliding with Indefatigable's other half-sister New Zealand.[18]

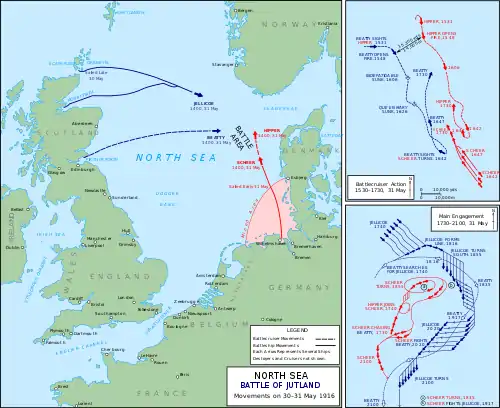

Battle of Jutland

On 31 May 1916, the 2nd BCS consisted of New Zealand (flagship of Rear-Admiral William Pakenham) and Indefatigable.[19] The squadron was assigned to Admiral Beatty's Battlecruiser Fleet which had put to sea to intercept a sortie by the High Seas Fleet into the North Sea. The British were able to decode the German radio messages and left their bases before the Germans put to sea. Admiral Franz von Hipper's battlecruisers spotted the Battlecruiser Fleet to their west at 15:20, but Beatty's ships did not spot the Germans to their east until 15:30. Two minutes later, he ordered a course change to east south-east to position himself astride the German's line of retreat and called his ships' crews to action stations. He also ordered the 2nd BCS, which had been leading, to fall in astern of the 1st BCS. Hipper ordered his ships to turn to starboard, away from the British, to assume a south-easterly course, and to reduce speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) to allow three light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Group to catch up. With this turn Hipper was falling back on the High Seas Fleet, then about 60 nautical miles (110 km; 69 mi) behind him. Around this time Beatty altered course to the east as it was quickly apparent that he was still too far north to cut off Hipper.[20]

This began what was to be called the "Run to the South" as Beatty changed course to steer east south-east at 15:45, paralleling Hipper's course, now that the range closed to under 18,000 yards (16,000 m). The Germans opened fire first at 15:48, followed by the British. The British ships were still in the process of making their turn as only the two leading ships, Lion and Princess Royal, had steadied on their course when the Germans opened fire. The British formation was echeloned to the right with Indefatigable in the rear and furthest to the west, and New Zealand ahead of her and slightly further east. The German fire was accurate from the beginning, but the British overestimated the range as the German ships blended into the haze. Indefatigable aimed at Von der Tann and New Zealand targeted Moltke while remaining unengaged herself. By 15:54, the range was down to 12,900 yards (11,800 m) and Beatty ordered a course change two points to starboard to open up the range at 15:57.

Around 16:00, Indefatigable was hit around the rear turret by two or three shells from Von der Tann. She fell out of formation to starboard and started sinking towards the stern and listing to port. Her magazines exploded at 16:03 after more hits, one on the forecastle and another on the forward turret. Smoke and flames gushed from the forward part of the ship and large pieces were thrown 200 feet (61.0 m) into the air.[21] It has been thought that the most likely cause of her loss was a deflagration or low-order explosion in 'X' magazine that blew out her bottom and severed the steering control shafts, followed by the explosion of her forward magazines from the second volley.[22] More recent archaeological evidence shows that the ship was actually blown in half within the opening minutes of the engagement with Von der Tann which fired only fifty-two 28 cm (11 in) shells at Indefatigable before the fore part of the ship also exploded.[23] Of her crew of 1,019, only three survived. While still in the water, two survivors, Able Seaman Frederick Arthur Gordon Elliott and Leading Signalman Charles Farmer, found Indefatigable's captain, C.F. Sowerby, who was badly wounded. Elliott and Farmer were later rescued by the German torpedo boat S16, but by then Sowerby had died of his injuries.[24] A third survivor, Signalman John Bowyer, was picked up by another unknown German ship. He was incorrectly reported as a crew member from Nestor in The Times on 24 June 1916.[25]

Indefatigable today

Indefatigable, along with the other Jutland wrecks, was belatedly declared a protected place under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, to discourage further damage to the resting place of 1,016 men.[26] Mount Indefatigable in the Canadian Rockies was named after the battlecruiser in 1917.[27] The wreck was identified in 2001, when it was found to have been heavily salvaged sometime in the past.[28] The most recent survey of the wreck by nautical archaeologist Innes McCartney revealed that the initial hits on the ship by Von der Tann caused 'X' turret magazine to detonate, blowing off a 40 m-long (130 ft) portion of the ship from forward of the turret to the stern. The supersonic shock-wave such an explosion generated was probably the reason for the very heavy loss of life on board. The fore part of the ship simply drifted on under its own momentum, still under fire, until it foundered. The two halves of the wreck are separated on the seabed by a linear distance of over 500 m (1,600 ft). The stern portion had not previously been discovered.[23]

Notes

- ↑ "cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

- ↑ The times used in this article are in UT, which is one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works.

Citations

- ↑ Roberts, pp. 26–28.

- ↑ Roberts, pp. 29, 43–44.

- ↑ Roberts, pp. 76–77, 80.

- ↑ Preston, p. 26.

- ↑ Roberts, pp. 81–84.

- ↑ Campbell (1978), p. 14.

- ↑ Roberts, p. 112.

- ↑ Brooks, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Roberts, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Campbell (1978), p. 13.

- ↑ Roberts, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Roberts, p. 41.

- ↑ "Charles FitzGerald Sowerby - the Dreadnought Project". Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ Roberts, p. 122.

- ↑ Massie, p. 39.

- 1 2 Massie, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Carlyon, p. 47.

- ↑ Burt, p. 103.

- ↑ Burt, p. 104.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 69, 71, 75.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 80–85.

- ↑ Roberts, p. 116.

- 1 2 McCartney (2017b), pp. 317–329

- ↑ Campbell (1986), p. 61.

- ↑ "John Bowyer – WW1 memorial and Life Story". Imperial War Museum & D C Thompson. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ "Statutory Instrument 2006 No. 2616 The Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 (Designation of Vessels and Controlled Sites) Order 2006". Queen's Printer of Acts of Parliament. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ↑ Rayburn, Alan (2001). Naming Canada: Stories About Canadian Place Names (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-8020-8293-0.

- ↑ McCartney (2017a), pp. 196–204

References

- Brooks, John (1995). "The Mast and Funnel Question: Fire-control Positions in British Dreadnoughts 1905–1915". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship 1995. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-654-5.

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-863-7.

- Campbell, John (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1978). Battle Cruisers. Warship Special. Vol. 1. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-130-4.

- Carlyon, Les (2001). Gallipoli. London: Transworld Publishers. ISBN 978-0-385-60475-8.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- McCartney, Innes (2017a). "The Battle of Jutland's Heritage under Threat: The Extent of Commercial Salvage on the Shipwrecks as Observed 2000–2016" (PDF). Mariner's Mirror. doi:10.1080/00253359.2017.1304701. S2CID 165003480.

- McCartney, Innes (2017b). "The Opening and Closing Sequences of the Battle of Jutland 1916 Re-examined: Archaeological Investigations of the Wrecks of HMS Indefatigable and SMS V4" (PDF). The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 46 (2): 317–329. Bibcode:2017IJNAr..46..317M. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12236. S2CID 164686388.

- Roberts, John (1997). Battlecruisers. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-068-7.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-917-2.