HMS Jupiter | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Namesake | Jupiter, Roman king of the gods |

| Builder | J & G Thomson, Clydebank |

| Laid down | 26 April 1894 |

| Launched | 18 November 1895 |

| Completed | May 1897 |

| Commissioned | 8 June 1897 |

| Decommissioned | February 1918 |

| Fate | Sold for scrapping 15 January 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Majestic-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 16,060 long tons (16,320 t) |

| Length | 421 ft (128 m) |

| Beam | 75 ft (23 m) |

| Draught | 27 ft (8.2 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 × 3-cylinder triple expansion steam engines, twin screws |

| Speed | 16 kn (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Complement | 672 |

| Armament | |

| Armour |

|

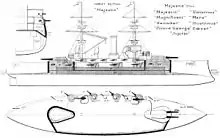

HMS Jupiter was a Majestic-class pre-dreadnought battleship of the Royal Navy. Commissioned in 1897, she was assigned to the Channel Fleet until 1905. After a refit, she was temporarily put in reserve before returning to service with the Channel Fleet in September 1905. In 1908 and rendered obsolete by the emergence of the dreadnought type of battleships, she once again returned to the reserve, this time with the Home Fleet. After another refit, she had a spell as a gunnery training ship in 1912.

Following the outbreak of World War I, Jupiter served with the Channel Fleet and then as a guard ship on the River Tyne. She was dispatched to Russia in February 1915 to serve as an icebreaker, clearing a route to Arkhangelsk while the regular icebreaker was undergoing a refit. She underwent her own refit later in 1915 and once completed, was transferred to the Suez Canal Patrol. She returned to England late 1916, and spent the remainder of the war based at Devonport. She was scrapped in 1920.

Design

HMS Jupiter was 421 feet (128 m) long overall and had a beam of 75 ft (23 m) and a draft of 27 ft (8.2 m). She displaced up to 16,060 long tons (16,320 t) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of two 3-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines powered by eight coal-fired, cylindrical fire-tube boilers. By 1907–1908, she was re-boilered with oil-fired models.[1] Her engines provided a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) at 10,000 indicated horsepower (7,500 kW). The Majestics were considered good seaboats with an easy roll and good steamers, although they suffered from high fuel consumption. She had a crew of 672 officers and ratings.[2]

The ship was armed with a main battery of four BL 12-inch (305 mm) Mk VIII guns in twin-gun turrets, one forward and one aft. The turrets were placed on pear-shaped barbettes; six of her sisters had the same arrangement, but her sisters Caesar and Illustrious and all future British battleship classes had circular barbettes.[1][2] Jupiter also carried a secondary battery of twelve QF 6-inch (152 mm) /40 guns. They were mounted in casemates in two gun decks amidships. She also carried sixteen QF 12-pounder guns and twelve QF 2-pounder guns for defence against torpedo boats. She was also equipped with five 18 in (457 mm) torpedo tubes, four of which were submerged in the ship's hull, with the last in a deck-mounted launcher.[2]

Jupiter and the other ships of her class had 9 inches (229 mm) of Harvey steel in their belt armour, which allowed equal protection with less cost in weight compared to previous types of armour. This allowed Jupiter and her sisters to have a deeper and lighter belt than previous battleships without any loss in protection.[1] The barbettes for the main battery were protected with 14 in (356 mm) of armor, and the conning tower had the same thickness of steel on the sides. The ship's armored deck was 2.5 to 4.5 in (64 to 114 mm) thick.[2]

Operational history

HMS Jupiter was laid down by J & G Thomson, Clydebank at Clydebank on 26 April 1894 and launched on 18 November 1895.[3] In February 1897 she was transferred to Chatham Dockyard,[4] where she was completed in May 1897.[3] She was commissioned on 8 June 1897 at Chatham Dockyard for service in the Channel Fleet. She was present at both the Fleet Review at Spithead for the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria on 26 June 1897 and the Coronation Fleet Review for King Edward VII on 16 August 1902.[5][4] Captain John Durnford was appointed in command in October 1899, followed by Captain Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne from December 1900. In March 1901 she visited Cork.[6] The following year she was part of a squadron visiting Nauplia and Souda Bay at Crete for combined manoeuvres between the Channel and Mediterranean fleets in September and October.[7] Captain Sir Richard Poore was appointed in command in December 1902.[8] On 1 January 1905, the Channel Fleet became the new Atlantic Fleet, making her an Atlantic Fleet unit. She was paid off at Chatham on 27 February 1905 to undergo a refit there, and her Atlantic Fleet service ended when she emerged from refit and was commissioned at Chatham into the Portsmouth Reserve on 15 August 1905. Jupiter was commissioned for service in the new Channel Fleet on 20 September 1905. This service ended on 3 February 1908 when she was paid off.[4] By this time, Jupiter had been surpassed in the role of front-line battleship by the new "all-big-gun" dreadnought battleships inaugurated by HMS Dreadnought in 1906.[9]

On 4 February 1908, Jupiter was recommissioned for reserve service in the Portsmouth Division of the new Home Fleet with a nucleus crew. She was flagship of the division from February to June 1909 and later second flagship of the 3rd Division, Home Fleet. During this service, she underwent refits at Portsmouth in 1909–1910, during which she received fire control equipment for her main battery, and 1911–1912.[10] From June 1912 to January 1913 she served as a seagoing gunnery training ship at the Nore.[10][4] In January 1913 she was transferred to the 3rd Fleet, and was based at Pembroke Dock and Devonport.[10]

World War I

When World War I broke out in August 1914, Jupiter was transferred to the 7th Battle Squadron of the Channel Fleet. During this service, she covered the passage of the British Expeditionary Force from England to France in September 1914. In late October 1914, Jupiter was reassigned to serve alongside her sister ship Majestic as a guard ship at the Nore. On 3 November 1914, Jupiter and Majestic left the Nore and relieved their sister ships Hannibal and Magnificent of guard ship duty on the Humber. In December 1914, Jupiter moved on to guard ship duty on the Tyne. On 5 February 1915, Jupiter was detached from her guard ship duty to serve temporarily as an icebreaker at Arkhangelsk, Russia, while the regular icebreaker there was under refit. In this duty, Jupiter made history by becoming the first ship ever to get through the ice into Arkhangelsk during the winter;[4] her February arrival was the earliest in history there,[10] although her bow was severely damaged by the voyage.[11]

Jupiter left Arkhangelsk in May 1915 to return to the Channel Fleet, and was paid off at Birkenhead on 19 May 1915. She then began a refit by Cammell Laird there that lasted until August 1915. Her refit completed, Jupiter was commissioned at Birkenhead on 12 August 1915 for service in the Mediterranean Sea on the Suez Canal Patrol. On 21 October 1915, she was transferred to the Red Sea to become guard ship at Aden and flagship of the Senior Naval Officer, Red Sea Patrol. She was relieved of flagship duty by the troopship RIM Northbrook of the Royal Indian Marine on 9 December 1915 and returned to the Suez Canal Patrol for Mediterranean service. This lasted from April to November 1916, with a home port in Port Said, Egypt.[4]

Jupiter left Egypt on 22 November 1916 and returned to the United Kingdom, where she was paid off at Devonport to provide crews for antisubmarine vessels. She remained at Devonport until April 1919, in commission as a special service vessel and auxiliary patrol ship until February 1918, when she was again paid off. After that she became an accommodation ship.[12][10] In April 1919, Jupiter became the first Majestic-class ship to be placed on the disposal list. She was sold for scrapping on 15 January 1920, and on 11 March 1920 was towed from Chatham to Blyth to be scrapped.[12]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Gibbons, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 4 Lyon & Roberts, p. 34.

- 1 2 Burt, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Burt, p. 165.

- ↑ "The Coronation - Naval Review". The Times. No. 36845. London. 13 August 1902. p. 4.

- ↑ "Naval and Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36392. London. 2 March 1901. p. 9.

- ↑ "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36883. London. 26 September 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36923. London. 12 November 1902. p. 8.

- ↑ Preston, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Preston, p. 7.

- ↑ Chernyshev.

- 1 2 Burt, p. 166.

References

- Burt, R. A. (2013) [1988]. British Battleships 1889–1904. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-173-1.

- Chernyshev, Alexander Alekseevich (2012). Погибли без боя. Катастрофы русских кораблей XVIII–XX вв [They died without a fight. Catastrophes of Russian ships of the XVIII-XX centuries] (in Russian). Moscow: Veche. ISBN 978-5-9533-6429-4.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books. ISBN 978-0-86101-142-1.

- Lyon, David & Roberts, John (1979). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 1–113. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

Further reading

- Dittmar, F. J. & Colledge, J. J. (1972). British Warships 1914–1919. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0380-4.