.jpg.webp)

Hacı Ahmet was a purported Ottoman cartographer linked to a 16th-century map of the world. Hacı Ahmet appended a commentary to the map, outlining his own life and an explanation for the creation of the map. But it is not clear whether Ahmet created the map, or whether he simply translated it into Turkish for use in the Ottoman world.

The map

Hacı Ahmet appended a lengthy commentary to a 16th-century map of the world annotated in the Turkish language, known as The Ottoman Mappa Mundi of Hacı Ahmet, amongst other titles, which opens with "Whoever wishes to know the true shape of the world, their minds shall be filled with light and their breast with joy."[1]

The map is heart shaped, otherwise known as a "cordiform projection," a style that was popular in sixteenth century Europe, and the extant copy was printed from wooden blocks in Venice, Italy, in 1559. It was kept until the late 18th century in the archives of the Venetian Council of Ten. The map is now part of the Heritage Library in the Qatar National Library.

Known as the "Mappamondo Hacı Ahmet", the map outlines legends and place-names in Turkish, and it may be the first map in Turkish ever published for sale to an Ottoman audience.[2][3] Whether the map is original, or was simply a translation into Turkish, it helps show how the people of the Ottoman Empire perceived themselves in relation to the wider world.[3] Three small spheres appear below the main map at the bottom of the page - the central graphic represents Earth and a number of satellite planets, while the left and right depict constellations.

Within the accompanying text of the map, Hacı Ahmet explains that the map was created to share knowledge of the shape of the world, especially of the New World. Specifically, Ahmet points out that the classical philosophers, such as Plato and Socrates, did not know about the newly discovered continent, which he says shows that the world is round.[1] He says that the New World demonstrates the "extent to which the Ottomans were participants in their own right in the process of physical expansion abroad and intellectual ferment at home that characterized the period of history commonly referred to as the Age of Exploration". Ahmet also assigns the Ottoman Empire's rulers and kingdoms to the celestial bodies represented in the lower quadrant of the map, a maneuver which has been interpreted as an effort to impose a hierarchical geopolitical system that preferences Ottoman rule above all other world powers.[4]

Authorship

The map is considered unlikely to be original, and was probably translated into Turkish by Ahmet.[2]

The map has specific European characteristics, in that it includes the use of Western terms,[1] suggesting Ahmet translated an older map into Turkish. In fact, throughout the map’s accompanying text, Ahmet emphasizes translation, stating that he “translated it from the language and alphabet of the Europeans into that of the Muslims”.[1] A further argument made against Ahmet's authorship is that the “heart-shaped form of the map had already been used by earlier European cartographers”.[2]

The map is "heart-shaped" and is constructed by a cordioform projection developed by 16th century cartographers and mathematicians including Johannes Werner (1468-1522), a German mathematician and geographer.

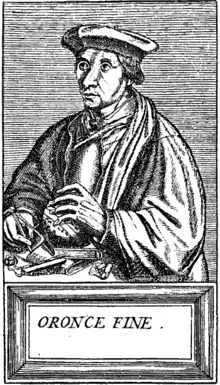

The map has been tentatively linked to several other geographers, including Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485-1557).[3] It has also been argued that it shares similarities with a map by the French cartographer Orontius (1494-1555), published in 1534.[3]

The Venetian connection

Ahmet claimed the map was made for Ottoman princes, and some of the sons of Suleyman the Magnificent were interested in maps of the world and had looked to Venice for their production.[3] This resulted in the development of Ottoman-Venetian relations, which offered "new interpretations of Venetian attitudes to the production of world maps for Ottoman clients".[2]

The map's printing in Venice helps to highlight aspects of Ottoman-Venetian relations. In the minds of Venetian publishers, it would be “a promising venture to produce a world-map for sale in the Muslim world”,[3] and so the production of world maps was financially rewarding for European publishers. Maps in the Turkish language were in demand by the Ottoman Empire, and maps were translated into Turkish to satisfy that market.[3]

The life of Hacı Ahmet

Nothing is known of Hacı Ahmet himself, other than his own account of his life recorded in the map text.[5]

“I, this poor, wretched and downtrodden Hacı Ahmet of Tunis studied since I was a small child in the Maghrib, in the city of Fez", says Ahmet in the text, which briefly describes his origins, saying that he was captured from the infidels and described how, in creating the map, he would regain his liberty.

According to the story, Ahmet was educated in Fez, and when a European nobleman purchased him, he was able to continue to practice his Islamic religion.[1][2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Casale, Giancarlo (2005). "Two Examples of Ottoman Discovery Literature from the mid-Sixteenth Century".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Arbel, B. (2002). "Maps of the world for ottoman princes? Further evidence and questions concerning the mappamondo of Hajji Ahmed'". Imago Mundi. 54: 19–99. doi:10.1080/03085690208592956. S2CID 155026279.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ménage, V. L. (1958). "'The Map of Hajji Ahmed' and its Makers". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 21 (2): 291–314. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00072682. S2CID 191444691.

- ↑ Casale, Giancarlo (2013). "Seeing the Past: Maps and Ottoman Historical Consciousness". In Cipa, H. Erdem; Fetvaci, Emine (eds.). Writing History at the Ottoman Court : Editing the Past, Fashioning the Future. Bloomington. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9780253008749.

- ↑ Fabri, A (1993). "The Ottoman Mappa Mundi of Hacı Ahmet of Tunis". Arab Historical Review for Ottoman Studies. 7–8: 31–37.

Further reading

- Arbel, Benjamin (1997). "Trading Nations: Jews and Venetians in the Early Modern Easter Mediterranean". Kirksville, Missouri: Sixteenth Century Journal. 28 (1).