| |

| Author | René Depestre |

|---|---|

| Original title | Hadriana dans Tous mes Rêves |

| Translator | Kaiama L. Glover |

| Language | French |

| Genre | magical realism |

| Publisher | Gallimard (French edition) Akashic Books (English edition) |

Publication date | 1988 |

Published in English | 2017 |

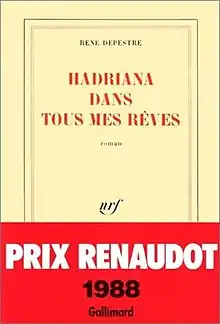

| Awards | Prix Renaudot |

| ISBN | 978-2-07-071255-7 (original French, 1988) ISBN 978-1-617-75533-0 (English, 2017) |

Hadriana in All My Dreams (French: Hadriana dans Tous mes Rêves) is a 1988 magical realism novel by Haitian author René Depestre. It is considered a major work of 20th century Haitian literature,[1] and possibly Depestre's most successful work.[2]

Synopsis

Part 1

Jacmel, Haïti, January 1938. The story begins with the death of Germaine Muzac Villaret-Joyeuse, the godmother of the narrator Patrick Altamonte. Germaine requests a butterfly mask to be put on her face at her death. According to local legend, this butterfly mask is actually a man, Balthazar Granchiré, cursed by a witch doctor. Granchiré promised Germaine that they would go to heaven together. Granchiré instead turns his interests to Hadriana Siloé, a young French woman to be married soon to a young Haitian man.

On her wedding day, Hadriana drinks a mysterious drink. At the moment of her vows "I do", she drops dead. Her grief-stricken parents desire to cancel the carnival, but a friend of Hadriana's declares that Hadriana had told her that she wanted her funeral to be a carnival. After many strange and supernatural happenings at the carnival, Hadriana is buried.

A few days afterward, it is discovered that Hadriana's grave is empty, leading everyone to the realization that Hadriana did not die, but was zombified. There are legends floating around that Hadriana went around to the homes of Jacmel, knocking on people's doors for help, but out of fear no one would help her. Patrick continues to think of Hadriana as the years go by.

Part 2

30 years have passed. Jacmel is mostly abandoned after the death of Hadriana Siloé. Patrick Altamont has traveled the world and taught many people, and constantly he thinks of his beloved Hadriana. He plans to write an essay on the Siloé affair, in which he offers several explanations on the origins of zombies, and wonders if zombies are a metaphor for the life of African slaves, and the Haitian people who cannot fight against their fate.

Hadriana returns to him one day as he is lecturing a group of students in Jamaica. They spend the night together, and she tells him her story.

Part 3

Hadriana recounts her life up to the fateful day of her wedding. She drinks a mysterious drink, likely poisoned by Balthazar Granchiré, which causes her to fall into a death-like stupor, but still retain her mental capacity and senses of sight, hearing, and touch. A witch doctor, Papa Rosanfer, wakes her up from her stupor and attempts to take her petit bon ange, but she is able to escape from him to Jamaica. Patrick concludes with telling the reader that it has been 10 years since they reunited and here their story ends.

Characters

- Patrick Altamont, the narrator of the novel

- Hadriana Siloé, the title character, a white French woman who is turned into a zombie on the day of her wedding

- Balthazar Granchiré, a satyriasic man-turned-butterfly who deflowers any young woman he can. In French, butterfly is papillion and the word papillonner means "to flit around from one thing to another", and can be used in the sense of having many affairs,[3] explaining why the sex maniac Balthazar was turned into a butterfly. The word "chiré" in Haitian Creole can be used to mean "fucked", meaning Granchiré's name can be translated as "Bigfuck".[4]

- Germaine Villaret-Joyeuse, the godmother of Patrick Altamont, who was gifted with 7 sets of loins

- Papa Rosanfer, a witch doctor who attempts to make a zombie out of Hadriana. His name could possibly be a pun on the French "enfer" meaning "hell".

Analysis

The novel is a response to the Westernized depiction of zombies. Haitian novelist Edwidge Danticat writes of Hadriana: "“The fact that we continue to be bombarded with the same old pedestrian zombie narratives written by foreigners and featuring Haitians makes this novel even more crucial.”[1] Zombies are a syncretization of European and African beliefs and often considered a symbol of slavery. In Haitian tradition, zombies are victims of their circumstances and the horror lies in their circumstances, not in their very being. However, thanks to Hollywood, a depiction of zombies as monstrous undead intent on destroying the living has been popularized in pop culture.[5][6] In the novel, Hadriana is an object of sympathy: despite her privileged status as a wealthy, white French woman, she is still abandoned by the people of Jacmel because of her zombification.[5]

Colonialism is a chief theme explored in the novel. The people of Jacmel idealize and objectify Hadriana due to her white French status, and later abandon Hadriana when she undergoes zombification, as this has in a way "creolized" her.[5] In the second part, Patrick muses on the origins of the zombie legend as a possible metaphor for the effects of colonialism on the black people of Haiti. The theme of Western Catholicism versus indigenous Vodou practices is also a theme that manifests in Hadriana: when Hadriana dies, the Catholic priest demands that a French woman be given a Christian funeral, however, the Haitians desire to celebrate Hadriana with a carnival, and ultimately the Haitians win.[7]

Some critics believe that Depestre intended to make an allegory of Haiti through the character of Hadriana, as the two names both begin with "Ha". However, Depestre denies this, saying that his intention above all was to tell a love story. Isabelle Constant believes by making the victim of zombification a white French woman rather than a black Haitian, Depestre breaks the trope that victims of zombification must be black.[8] Dayan takes the opposite view, saying that the zombification of Hadriana tells "a story that promotes the comfortable illusion that a white can take on the burden of blacks, symbolically redeeming those who are finally iredeemable."[4] Hadriana has also been described as an exoticist novel, and a product of the exiled Depestre's attempt to compensate for his own loss of his native nation and a response to the deterritorialization of Haiti.[7]

Hadriana's sexuality is also given significant focus in the book. She recounts several sexual encounters she had, including a same-sex encounter with one of her best friends, before her wedding night. This is put in juxtaposition with how the city of Jacmel idealizes Hadriana as a virgin saint. Hadriana, however, rejects this perception of her and after escaping from zombification, decides to live her life according to her own desires. Glover writes that Hadriana in All My Dreams is Depestre's rejection of socialism, Marxism, and the sacrifice of individual liberty. Rather than have Hadriana be at the mercy of those that need or want something from her- the people of Jacmel, Papa Rosanfer,- she chooses her own individual fate. [5]

Reception

Hadriana in All My Dreams won the Prix Renaudot in 1988. It was the first time a Haitian writer ever won the Prix Renaudot,[9] and the first time a Haitian writer ever won one of France's six major literary awards for a novel(the others being Prix Goncourt, Prix Femina, Prix Médicis, Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française, and Prix Interallié). As of 2013, Depestre remains the only Haitian winner of the Prix Renaudot, and one of only 2 Haitian writers to ever receive one of the six major French literary awards in the area of novels.[10] Hadriana also won the 1988 prize for "Best Novel" from Société des gens de lettres.[11][12] Within 5 years, it had sold nearly 200,000 copies.[4]

Hadriana in All My Dreams received critical acclaim for its poetic style of writing and social commentary. The March 2017 issue of Kirkus Reviews wrote: "By the time you've wandered these spooky, sultry corridors of Haiti's collective subconscious, you're persuaded that the true sorcery being practiced here is that of a mature artist coming to terms—and making peace—with 'the natural, the comical, the playful, the sensual, and the magical aspects of Jacmel's painful past.' An icon of Haitian literature serves up a hotblooded, rib-ticking, warmhearted mélange of ghost story, cultural inquiry, folk art, and véritable l’amour."[13] Poornima Apte of Booklist wrote: "Depestre presents a rich and nuanced exploration of large and significant themes expertly couched in one fantastical, expertly translated tale."[14]

Bogi Takács of tor.com praised Hadriana in All My Dreams, writing "It can be read both as a vividly depicted story of magic and zombies, and as compelling social commentary. It's a book that's bursting at the seams with detail—don't be surprised if something jumps out at you from among the pages."[1] Novelist Ben Fountain named Hadriana in All My Dreams as one of his top 10 books about Haiti.[15]

Former Yale professor Joan Dayan criticized the novel, writing that Hadriana was an idealization that "contributes as much to false generalizations about Haiti as any denigration by Spenser St. John or those other accounts of the "Magic Island" or "Black Baghdad"...Depestre abandons the inhabitants of Haiti to their fate, apparently forgetting their continued struggles against dictatorship, repression, and poverty. All that remains of his Haiti is a portrait of black, poor, apathetic husks of humanity, who can never awake into freedom." Dayan also criticizes Depestre for participating in the perpetration of rape culture.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 Takács, Bogi. "QUILTBAG+ Speculative Classics: Hadriana in All My Dreams by René Depestre". tor.com. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ↑ Salien, Jean-Marie (2000). "Croyances populaires haïtiennes dans Hadriana dans tous mes rêves de René Depestre". The French Review. 74 (1): 82–93. ISSN 0016-111X. JSTOR 399293. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ↑ Blanchaud, Corinne (2013). "René Depestre, l'homme-banian ou les tribulations du « Tout en un »". Haïti: 53. doi:10.3917/puv.brod.2013.01.0053. ISBN 9782842923594. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Dayan, Joan (1993). "France Reads Haiti: René Depestre's Hadriana dans tous mes rêves". Yale French Studies (83). doi:10.2307/2930092. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Glover, Kaiama L. (2005). "Exploiting the Undead: the Usefulness of the Zombie in Haitian Literature". Journal of Haitian Studies. 11 (2). ISSN 1090-3488. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ↑ Wilentz, Amy (30 October 2012). "Opinion | A Zombie Is a Slave Forever". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- 1 2 Munro, Martin (2003). "Exile, Deterritorialization, and Exoticism in René Depestre's "Hadriana dans tous mes rêves"". Journal of Haitian Studies. 9 (1). ISSN 1090-3488.

- ↑ Constant, Isabella (2008). "Le rêve dans le roman africain et antillais". Lettres du Sud. Kathala: 107–124. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ Poinsot, Jérôme (2016). René Depestre, Hadriana dans tous mes rêves. Paris: Honoré Champion. ISBN 9782745331007. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ Chaulet Achour, Christiane (1 March 2013). "Prix littéraires et réception de la littérature haïtienne". Littérature Hors Frontière (in French): 187–213. doi:10.3917/puv.brod.2013.01.0187. ISBN 9782842923594. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ "Grand Prix SDGL". Official Site of SDGL. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ Triay, Philippe. "L'écrivain haïtien René Depestre lauréat du Grand prix de la Société des gens de lettres". La Première. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ↑ "Hadriana in All My Dreams. Kirkus Reviews". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ Apte, Poornima (April 15, 2017). "Hadriana in All My Dreams". Booklist. 113 (16): 30–21. ISSN 0006-7385. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ Fountain, Ben. "Ben Fountain's top 10 books about Haiti". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2022.