| Haloxylon ammodendron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Amaranthaceae |

| Genus: | Haloxylon |

| Species: | H. ammodendron |

| Binomial name | |

| Haloxylon ammodendron | |

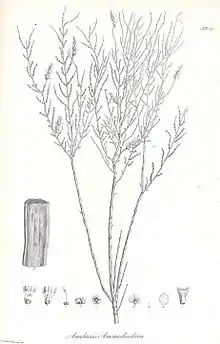

Haloxylon ammodendron, the saxaul, black saxaul, sometimes sacsaoul or saksaul (Russian: саксау́л, tr. saksaúl, which is from Kazakh: сексеуіл), is a plant belonging to the family Amaranthaceae.

Description

The saxaul ranges in size from a large shrub to a small tree, 2–8 metres (6+1⁄2–26 feet), rarely 12 m (39 ft) tall. It has a brown trunk up to 25 centimetres (10 inches) in diameter. The wood is heavy and coarse and the bark is spongy and water-soaked. The branches of the current year are green; older branches are brown, or gray to white. The leaves are reduced to very small cusp-like scales, so that the plant appears nearly leafless.[1]

The inflorescences consist of short lateral shoots borne on stems of the previous year. The flowers are bisexual or male, very small, as long as or shorter than the bracteoles. The flowering period is from March to April.[1]

In fruit, the perianth segments develop spreading pale brown or white wings. The diameter of the winged fruit is about 8 millimetres (3⁄8 in). The seed is 1.5 mm (1⁄16 in) in diameter. The fruiting period is October to November.[1]

Taxonomy

The species was first published in 1829 by Carl Anton von Meyer as Anabasis ammodendron C.A.Meyer. In 1851 Alexander Bunge combined it to genus Haloxylon as Haloxylon ammodendron (C.A.Meyer) Bunge.[1]

Synonyms are: Arthrophytum ammodendron (C.A.Meyer) Litw., Arthrophytum haloxylon Litw., Haloxylon pachycladum M.Pop., and Haloxylon aphyllum (Minkw.) Iljin..[1]

A related saxaul species is Haloxylon persicum (or white saxaul).

Distribution and habitat

The saxaul is distributed in the lowlands of Central Asia – including southern Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, western Uzbekistan,[2] Iran, west Afghanistan, Mongolia and China, namely Xinjiang and Gansu.[3] It also occurs incidentally in the west of Kirghizstan and Tajikistan.[2] It is a psammophyte, and grows in sandy deserts, on sand dunes, and in steppe up to 1,600 m (5,200 ft) above sea level. In Central Asia it often forms 'saxaul forests', in Iran it usually grows more scattered.[1] It also grows in the sandy parts of Saudi Arabia.

Ecology

Turcmenigena varentzovi (saxaul longhorn beetle, Varentsov's longhorn beetle) is a pest of the black saxaul tree in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Dark cone-like galls are often found on the plants.[1]

A parasitic plant, Cistanche deserticola, that grows on the roots of the saxaul is prized in Chinese medicine as the 'ginseng of the desert'.

Uses

Saxaul is planted on a large scale in the afforestation of arid areas in China. Being highly drought-resistant, it has played an important role in the establishment of shelter belts and the fixation of sand dunes as a counter to desertification.[4][5]

The thick bark of the saxaul tree stores water. Quantities of the bark may be pressed for drinking water, making saxaul an important source of water in arid regions where it grows.[6]

Saxaul is a traditional Turkmen firewood. It was heavily harvested in some provinces in Turkmenistan as it was used for fuel to fight the 2008 Central Asia energy crisis.[7] In the Gobi desert, the saxaul is often the only kind of tree found. It used to be, and in some place still is, the only kind of wood that nomads can use for heating and cooking.

When the Russian Imperial Navy brought the first steamships into the land-locked Aral Sea, the local Governor-General Vasily Perovsky ordered the commander of Fort Aralsk to collect "as large as possible supply" of saxaul wood (Anabasis saxaul, in the source) for use by the new steamships on their maiden navigation of 1851. Unfortunately for the Russian Naval budget (but probably quite fortunately for the saxaul itself), saxaul wood turned out to be not particularly suitable for steamships, as the hard and resinous wood was difficult to cut, and knotty and crooked saxaul logs could not be stored space-efficiently in the ships' holds. Therefore, starting from 1852, the Aral Flotilla switched to coal as its main fuel, despite the remarkable costs of shipping it by caravan from Orenburg.[8]

The Uzbek government has also planted the trees in the Aral Desert to help prevent the spread of toxic salts left behind when the sea dried up, which have caused numerous health problems for people living on the perimeter of the desert.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hedge, I. C. (1997). Rechinger, Karl Heinz; et al. (eds.). Haloxylon in Flora Iranica Bd. 172, Chenopodiaceae. Graz: Akad. Druck. pp. 317–318. ISBN 3-201-00728-5.

- 1 2 "Haloxylon ammodendron (C.A.Mey) Bunge - Саксаул зайсанский". Дикие родичи культурных растений. Агроэкологический атлас России и сопредельных стран: экономически значимые растения, их болезни, вредители и сорные растения. 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ http://www.catalogueoflife.org/col/details/species/id/359e520da928436c4e3eb010b2f3f19f

- ↑ "Sand stoppers of China's Inner Mongolia". China.org.cn. 2010-11-22. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ↑ Huang PX. (2000), No-irrigation vegetation and its restoration in arid area., Beijing: Science Press.

- ↑ The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants. United States Department of the Army. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. 2009. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-60239-692-0. OCLC 277203364.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Farangis Najibullah (January 13, 2008). "Tajikistan: Energy shortages, extreme cold create crisis situation". EurasiaNet. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ Michell, John; Valikhanov, Chokan Chingisovich; Venyukov, Mikhail Ivanovich (1865). "The Russians in Central Asia: their occupation of the Kirghiz steppe and the line of the Syr-Daria : their political relations with Khiva, Bokhara, and Kokan : also descriptions of Chinese Turkestan and Dzungaria; by Capt. Valikhanof, M. Veniukof and others. Translated by John Michell, Robert Michell". E. Stanford: 327–328.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Qobil, Rustam (2015). "Special Report – Waiting for the sea". BBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

External links

Media related to Haloxylon ammodendron at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Haloxylon ammodendron at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Haloxylon ammodendron at Wikispecies

Data related to Haloxylon ammodendron at Wikispecies