Harry T. Burn | |

|---|---|

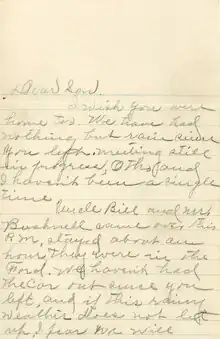

Photo of Burn taken the year he first took seat in the Tennessee legislature | |

| Member of the Tennessee Senate from the 7th district | |

| In office 1948–1952 | |

| Member of the Tennessee House of Representatives from the McMinn County, Tennessee district | |

| In office 1918–1922 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 12, 1895 Mouse Creek, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | February 19, 1977 (aged 81) Niota, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Mildred Tarwater (1933–1935, div.) Ellen Cottrell (1937–1977) |

| Children | Harry Thomas Burn Jr |

| Parent(s) | James Lafayette Burn Febb King Ensminger |

Harry Thomas Burn Sr. (November 12, 1895 – February 19, 1977)[1] was a Republican member of the Tennessee General Assembly for McMinn County, Tennessee. Burn became the youngest member of the state legislature when he was elected at the age of twenty-two. He is best remembered for action taken to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment during his first term in the legislature.[2]

Childhood and education

Born in Mouse Creek[3] (now Niota, Tennessee), Burn was the oldest of four children of James Lafayette Burn (1866–1916) and Febb Ensminger Burn (1873–1945). His father was the stationmaster at the Niota depot, and an entrepreneur in the community. His mother worked as a teacher after her graduation from U.S. Grant Memorial University (now Tennessee Wesleyan University). She later ran the family farm. Burn's siblings were James Lane "Jack" (1897–1955), Sara Margaret (1903–1914), and Otho Virginia (1906–1968). Burn graduated from Niota High School in 1911. He worked for the Southern Railway from 1913 to 1923.[3]

19th Amendment

The Nineteenth Amendment, regarding female suffrage, was proposed by Congress on June 4, 1919. The amendment could not become law without the ratification of a minimum thirty-six of the forty-eight states. By the summer of 1920, thirty-five of the forty-eight states had ratified the amendment, with a further four states called upon to hold legislative voting sessions on the issue. Three of those states refused to call special sessions, but Tennessee agreed to do so. This session was called to meet in August 1920.[4] The effort to pass the legislation in the House was led by Joe Hanover. Banks Turner and Burn were two critical votes that ultimately tipped the balance to ratification.[5]

Burn had originally intended to vote for the amendment.[3] After being pressured by party leaders and receiving misleading telegrams from his constituents telling him his district was overwhelmingly opposed to woman suffrage, he began to side with the Antisuffragists.[3] However, a letter from his mother asking him to vote in favor of the amendment helped to change his mind: Febb Ensminger Burn of Niota had written a long letter to her son, which he held in his coat pocket during the voting session on August 18, 1920. The letter contained the following:

Dear Son:

...

Hurrah and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt. I noticed Chandlers' speech, it was very bitter. I’ve been watching to see how you stood but have not seen anything yet ... Don't forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. ‘Thomas Catt’ with her "Rats." Is she the one that put rat in ratification, Ha! No more from mama this time.

...

With lots of love, Mama.[6]

After much debating and argument, the result of the vote was 48-48. After Burn voted twice to "table" the amendment, the house speaker called for a vote on the "merits".[3] Burn followed his mother's advice and voted "aye". His vote broke the tie in favor of ratifying the amendment. He responded to attacks on his integrity and honor by inserting a personal statement into the House Journal, explaining his decision to cast the vote in part because "I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification."[6]

As anti-suffragists had been fighting and preparing for this moment over the summer, they became very enraged when they discovered the news of Burn's decision. Contrary to popular belief, Burn was not chased out of the capitol by an angry mob of anti-suffragists.[3] But the anti-suffrage forces accused him of bribery and a grand jury was called to investigate the accusations. Burn narrowly won reelection to a second term in the house after a grueling campaign back home in McMinn County.[3]

Public career

Burn held public office for much of his adult life, including positions in the State House of Representatives, 1918–1922; State Senate, 1948–1952; state planning commission, 1952–1970;[3] and as delegate for Roane County to the Tennessee constitutional conventions of 1953, 1959, 1965, and 1971.[3] Burn ran unsuccessfully for the Republican gubernatorial nomination in 1930.[3]

Personal life

In 1923, Burn was admitted to the Tennessee Bar and practiced law in Rockwood and Sweetwater. In 1951, he became President of the First National Bank in Rockwood.

Burn was a member of several civic and fraternal organizations, including the National Society Sons of the American Revolution, serving as President-General for the 1964–1965 term.

He was briefly married to Mildred Rebecca Tarwater from 1933 to 1935. He married Ellen Folsom Cottrell (1908–1998) in 1937. The couple had one child, Harry T. Burn Jr. (1937–2016).

Burn died at his home in Niota.[3]

In popular culture

Burn is portrayed by Peter Berinato in the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels.

Winter Wheat, a musical about the ratification of the 19th Amendment in Tennessee, premiered in 2016 after its original version had a limited run in 2014; Harry Burn, his mother Febb, and his younger brother Jack, are major characters. The play was performed again in 2020.[7]

Burn's great-grandnephew, Tyler L. Boyd, wrote a comprehensive biography of Burn, called Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn: Woman suffrage, free elections, and a life of service, and published in 2019.[3]

Burn is portrayed in the 2022 musical Suffs.

References

- ↑ Harry T. Burn at Find a Grave

- ↑ Mettler, Katie (10 August 2020). "A mother's letter, a son's choice, and the incredible moment women won the vote". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Boyd, Tyler L. (5 August 2019). Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn: Woman suffrage, free elections, and a life of service. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-4671-4318-9.

- ↑ Hiers, Cheryl (2009). "The nineteenth amendment and the war of the roses". BlueShoe Nashville. Nashville, TN.

- ↑ Thornton, Lasherica (15 August 2020). "West Tennessee's role in women's right to vote". Jackson Sun.

- 1 2 "Personal letter from Febb Burn to son, Tennessee legislator Henry Burn, recommending a vote in favor of women's suffrage" (PDF). Teach TN History. 11 July 1920.

- ↑ "World premiere of Winter Wheat begins performances 7/29 at Barter Theatre". Broadway World. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

Sources

- "Battle began for suffrage many years ago". Nashville Tennessean. Vol. 14, no. 100. 19 August 1920.

- "Suffrage Amendment Adopted by House". Nashville Tennessean. Vol. 14, no. 100. 19 August 1920.

- "Tennessee ratifies amendment giving women of U.S. vote". The Commercial Appeal. Vol. 104, no. 50. 19 August 1920.

- "Decisive action taken today in suffrage battle". The Nashville Tennessean. Vol. 14, no. 102. 21 August 1920.

- "New election laws may be necessary". The Nashville Tennessean. Vol. 14, no. 100. 19 August 1920.

- "The case of Harry T. Burn". The Nashville Tennessean. Vol. 14, no. 102. 21 August 1920.

- "Word from mother won for suffrage". The Nashville Tennessean. Vol. 14, no. 101. 20 August 1920.

- "Burn changed vote on advice of his mother". The Commercial Appeal. 20 August 1920.

- Heirs, Cheryl (8 August 2001). "The nineteenth amendment and the war of the roses". BlueShoe Nashville Guide.

- Boyd, Tyler L. (5 August 2019). Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn: Woman suffrage, free elections, and a life of service. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-4671-4318-9.

External links

- "Harry T. Burn". Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection. Knox County Public Library.

- "Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn: Woman suffrage, free elections, and a life of service". Arcadia Publishing.

- Harry T. Burn at Find a Grave