Harvey Quaytman | |

|---|---|

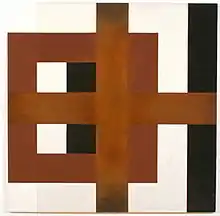

Riley Mumbling to Himself at Night (1961-63) | |

| Born | April 20, 1937 |

| Died | April 8, 2002 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Boston Museum School |

| Movement | Abstract art |

| Awards | Guggenheim Fellowship, Elizabeth Foundation Prize for Painting, American Academy of Arts and Letters - Academy Award in Art, National Endowment for the Arts fellowship |

| Website | McKee Gallery, Nielson Gallery |

Harvey Quaytman (April 20, 1937 - April 8, 2002) was a geometric abstraction painter best known for large modernist canvases with powerful monochromatic tones, in layered compositions, often with hard edges - inspired by Malevich and Mondrian. He had more than 60 solo exhibitions in his career, and his works are held in the collections of many top public museums.

Life and career

Harvey Quaytman was born on April 20, 1937[1] in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York. His father, Marcus Quaytman, was a 1920 Jewish immigrant from Lodz, Poland and a certified public accountant, and his mother Rose Quaytman was a piano teacher from Lawrence, Long Island, New York.[2] In 1940 his father and grandfather were killed in a train crash in Queens NY.[3]

From 1955-1957, he attended Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York, but graduated in 1959 with a BFA from Tufts University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA.[4] It was there he met and married fellow painting student, future award-winning American postmodern poet Susan Howe, and in 1961 they had a daughter, Rebecca Quaytman, who is now a well-regarded abstract painter.[5]

In 1963 the family moved to Soho, New York City, but two years later the parents divorced, and Susan married Harvey's close friend, sculptor David von Schlegell.[5]

In 1966 Harvey met and later married the painter Frances Barth. They were together until their divorce in 1980. In November 1989, Quaytman was married for a third time, in his studio, to Margaret Moorman, a writer.[2] Their daughter Emma was born in 1989.[4]

Harvey Quaytman died in New York on April 8, 2002, from cancer.[4]

Awards and honors

In both 1972 and 1975, he was awarded a CAPS Grant, and in both 1979 and 1985, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.[6] In 1983, he received an Artist’s Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and by 1993 he became a Member of the National Academy of Design. In 1994, he won the Elizabeth Foundation Prize for Painting, and finally, in 1997, he received the Academy Award in Art from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[4][7]

Works

In the context of artistic movements, Harvey Quaytman was considered an anachronism. During his career, from the late 1960s to late 1990s, he continued to relentlessly explore Geometric Abstraction and Modernism - fields in which the innovation had been considered largely developed by the end of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet he pushed ahead, and according to critics he became bolder over time - more innovative, assured and successful in each decade. Even in his later years, he was recognized for finding dynamic, new forms of abstraction.[8]

In the late 1960s and 1970s, situated in settings like the Whitney Biennials, his paintings were easily recognized among the crowd due to his masterful use of shaped canvases.[9] They were large, often curved, and frequently enclosing wall space. The painting itself blended elements from abstract expressionism and geometric abstraction, over time shifting further towards geometry. The surfaces were never simple. By the 1980s, he returned to the rectangular and square canvas, and eventually to the cruciform (cross) shape, which would become a focus for the next decade. "Harvey Quaytman's shaped canvases are among the most impressive;"[10] and "Some of the best shaped canvases of the last two decades have come from Harvey Quaytman. But in this selection of new work, the painter has, so to speak, drawn in his horns, confining himself to the right angle and in most cases to a cruciform image." -Vivien Raynor, New York Times, 1986[11]

By the 1990s, he had abandoned the curve, and remained fixed to the cross, often in the shape of the canvas or upon it.[12] He frequently blended rust (which he first used in 1969) and acrylic, as well as glass - creating a spectrum of textures.[8] After 1998, he was unable to work.[13]

After his death in 2002, McKee Gallery, his longtime representative, organized a lauded retrospective titled "Harvey Quaytman: A Survey of Paintings and Drawings 1969-1998".[8][14]

Later retrospectives were organized by McKee in 2005, "Harvey Quaytman’s current show, Flying the Colors, is strong, deep, and soaring. A celebration of the artist’s bold color work, it features twelve outstanding paintings drawn from the past twenty-five years." -Michael Brennan, Brooklyn Rail;[15] and 2011, "Harvey Quaytman: A Sensuous Geometry, Works from 1986-1997"[9][16] "Quaytman’s paintings are extremely cerebral, yet full of sensual grace. He moved abstract painting beyond the mundane into the realm of cognitive understanding through a heightened sensory involvement with materials and an ultimate clarity of space." -Robert C. Morgan, Brooklyn Rail[17] Photos of the exhibit were posted by Contemporary Art Daily.[18]

In 2018 the Berkeley Art Museum mounted a retrospective and symposium, "Harvey Quaytman: Against the Static."[19]

Today, his works are in the collections of several public museums:

- Museum of Modern Art[20]

- Whitney Museum of American Art[7]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston[21]

- Minneapolis Institute of Art[22]

- Corcoran Gallery of Art[23]

- Carnegie Museum of Art[24]

- Neuberger Museum of Art[7]

- See Talk:Harvey Quaytman for a list of 40 additional public collections

Quaytman's remaining work is represented by McKee Gallery in New York,[25] Blum & Poe[26] in Los Angeles, and Nielson Gallery in Boston.[27]

References

- ↑ "Social Security Death Index".

- 1 2 "Margaret Moorman, Writer, Is a Bride". The New York Times. November 26, 1989.

- ↑ "Art in America Magazine". June 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Johnson, Ken (April 15, 2002). "Harvey Quaytman Obituary". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Cate McQuaid. "Signs and Sensibility". Boston Globe. November 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Guggenheim Foundation Announcement of Fellows". Archived from the original on 2013-01-03.

- 1 2 3 "Harvey Quaytman Bio at mcKee Gallery".

- 1 2 3 Curt Barnes. "Harvey Quaytman: A Tribute". Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- 1 2 Donald Goddard. "Harvey Quaytman: A Survey of Paintings and Drawings 1969-1998". Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ↑ Vivien Raynor. "Two arts shows are merged, with little in common". The New York Times. November 10, 1985.

- ↑ Vivien Raynor."ART: The Outsiders". The New York Times. January 17, 1986.

- ↑ "Currently Hanging, by Mario Naves". The New York Observer. 13 October 2003. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Art Critical, Oct. 2, 2003 - Harvey Quaytman at McKee Gallery, by David Cohen". Archived from the original on 2012-10-01. Retrieved 2013-01-17.

- ↑ "McKee Gallery, Sep. 2003 - Harvey Quaytman: A Survey of Paintings and Drawings 1969-1998".

- ↑ "Brooklyn Rail April 2005 - Harvey Quaytman, by Michael Brennan". April 2005.

- ↑ "McKee Gallery, Nov. 3, 2011".

- ↑ "Brooklyn Rail, Mar. 2011 - Hard-Edgeness in American Abstract Painting, by Robert C. Morgan". 4 March 2011.

- ↑ "Contemporary Art Daily, Jul. 22, 2011 - Harvey Quaytman".

- ↑ BAMPFA.org: Harvey Quaytman: Against the Static

- ↑ "MoMA Online Collection - Harvey Quaytman".

- ↑ "Museum of Fine Art Boston Online Collection - Harvey Quaytman".

- ↑ "Minneapolis Institute of Art Online Collection".

- ↑ "Corcoran Gallery - Harvey Quaytman Exhibition". Archived from the original on 2013-01-07.

- ↑ "Carnegie Museum of Art Online Collection".

- ↑ "Harvey Quaytman - McKee Gallery". mckeegallery.com. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ↑ "Artists « Blum & Poe". www.blumandpoe.com. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- ↑ "Nielsen Gallery". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2013-01-17.