Hauser bases, also called magnesium amide bases, are magnesium compounds used in organic chemistry as bases for metalation reactions. These compounds were first described by Charles R. Hauser in 1947.[1] Compared with organolithium reagents, the magnesium compounds have more covalent, and therefore less reactive, metal-ligand bonds. Consequently, they display a higher degree of functional group tolerance and a much greater chemoselectivity.[2] Generally, Hauser bases are used at room temperature while reactions with organolithium reagents are performed at low temperatures, commonly at −78 °C.

Structure

Solid state structure

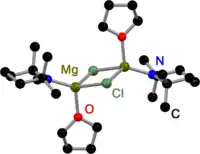

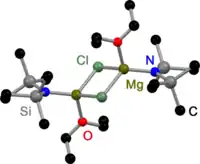

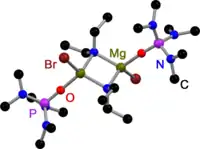

Like all Grignard dimers,[3] Hauser bases derived from 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (TMP)[4] and HMDS[5] are bridged by halides in the solid state. In contrast to Grignard reagents, dimeric amido bridged Hauser bases exist, too. All have one in common: they are bridged by less bulky amido ligands such as Et2N−,[4] Ph3P=N−[6] and iPr2N−.[7] The displacement to halide bridges may be a result of the bulky groups on the amide ligand.

TMP Hauser Base in the solid state |

HMDS Hauser Base in the solid state |

Diethylamido Hauser Base in the solid state |

Solution structure

Although there is a great deal of information on the utility of these reagents, very little is known regarding the nature of Hauser bases in solution. One reason for that lack of information is that Hauser bases show a complex behaviour in solution. It was proposed that it could be similar to the Schlenk equilibrium of Grignard reagents in ether solution, where more than one magnesium containing species exists.[8] In 2016, Neufeld et al. showed by diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY)[9] that the solution structure of iPr2NMgCl is best represented by the common Schlenk equilibrium:[10]

- iPr2NMgCl (A) ⇌ (iPr2N)2Mg (B) + MgCl2

This equilibrium is highly temperature dependent with heteroleptic (A) to be the main species at high temperatures and homoleptic (B) at low temperatures. Dimeric species with bridging chlorides and amides are also present in the THF solution, although alkyl magnesium chlorides do not dimerize in THF. At low temperatures, where an excess of MgCl2 is available MgCl2 co-coordinated species are present in solution, too.[10]

Preparation

The Hauser bases are prepared by mixing an amine and a Grignard reagent.

- R2NH + R′MgX → R2NMgX + R′H X = Cl, Br, I

Uses

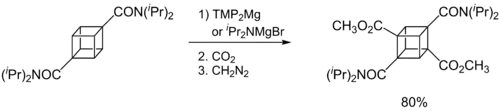

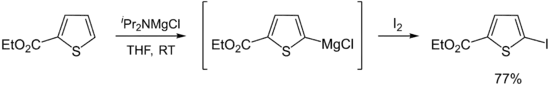

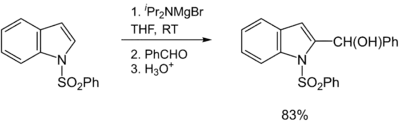

Hauser bases are generally used as metalation reagents, like organolithiums or metal amides. The breakthrough in synthetic protocols of Hauser bases culminates in the 1980s and 1990s. Eaton and coworkers showed that iPr2NMgBr selectively magnesiate carboxamides in ortho position.[11] Later, Kondo, Sakamo and co-workers reported the utility of iPr2NMgX (X = Cl, Br) as selective deprotonation reagents (exclusively at the 2-position) for heterocyclic thiophene [12] and phenylsulphonyl-substituted indoles.[13]

A major disadvantage of Hauser bases is their poor solubility in THF. In consequence, the metalation rates are slow and a large excess of base is required (mostly 10 equiv.). This circumstance complicates the functionalization of the metaled intermediate with an electrophile. Better solubility and reactivity can be achieved by adding stoichiometric amounts of LiCl to the Hauser base. These so-called Turbo-Hauser bases like e.g. TMPMgCl·LiCl and iPr2NMgCl·LiCl are commercially available[14] and show an enhanced kinetic basicity, excellent regioselectivity and high functional group tolerance for a large number of aromatic and heteroaromatic substrates. [15][16]

Commonly used Hauser bases

- iPr2NMgX

- TMPMgX (TMP = 2,2,6,6,tetramethylpiperidino, X= Cl, Br)

References

- ↑ Hauser C. R., Walker H (1947). "Condensation of Certain Esters by Means of Diethylaminomagnesium Bromide". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 69 (2): 295. doi:10.1021/ja01194a040.

- ↑ Li–Yuan Bao, R.; Zhao, R.; Shi, L. (2015). "Progress and developments in the turbo Grignard reagent i-PrMgCl·LiCl: a ten-year journey". Chem. Commun. 51 (32): 6884–6900. doi:10.1039/C4CC10194D. PMID 25714498.

- ↑ e.g.; Seven, Ö.; Bolte, M.; Lerner, H.-W. (2013). "Di-μ-bromido-bis[(diethyl ether-κO)(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)magnesium]: the mesityl Grignard reagent" (PDF). Acta Crystallogr. E. 69 (7): m424. doi:10.1107/S1600536813017108. PMC 3772445. PMID 24046588.

- 1 2 García–Álvarez, P.; Graham, D. V.; Hevia, E.; Kennedy, A. R.; Klett, J.; Mulvey, R. E.; O'Hara, C. T.; Weatherstone, S. (2008). "Unmasking Representative Structures of TMP-Active Hauser and Turbo-Hauser Bases". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (42): 8079–8081. doi:10.1002/anie.200802618. PMID 18677732.

- ↑ Yang, K.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Huang, J.-Y.; Lin, C.-C.; Lee, G.-H.; Wang, Y.; Chiang, M. Y. (2002). "Synthesis, characterization and crystal structures of alkyl-, alkynyl-, alkoxo- and halo-magnesium amides" (PDF). J. Organomet. Chem. 648 (1–2): 176–187. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(01)01468-1.

- ↑ Batsanov, A. S.; Bolton, P. D.; Copley, R. C. B.; Davidson, M. G.; Howard, J. A. K.; Lustig, C.; Price, R. D. (1998). "The metallation of imino(triphenyl)phosphorane by ethylmagnesium chloride: The synthesis, isolation and X-ray structure of [Ph3P=NMgCl·O=P(NMe2)3]2". J. Organomet. Chem. 550 (1–2): 445–448. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(97)00550-0.

- ↑ Armstrong D. R.; García–Álvarez, P.; Kennedy, A. R.; Mulvey, R. E.; Parkinson, J. A. (2010). "Diisopropylamide and TMP Turbo-Grignard Reagents: A Structural Rationale for their Contrasting Reactivities". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (18): 3185–3188. doi:10.1002/anie.201000539. PMID 20352641.

- ↑ Neufeld, Roman.: DOSY External Calibration Curve Molecular Weight Determination as a Valuable Methodology in Characterizing Reactive Intermediates in Solution. In: eDiss, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. 2016.

- ↑ Neufeld, R.; Stalke, D. (2015). "Accurate Molecular Weight Determination of Small Molecules via DOSY-NMR by Using External Calibration Curves with Normalized Diffusion Coefficients". Chem. Sci. 6 (6): 3354–3364. doi:10.1039/C5SC00670H. PMC 5656982. PMID 29142693.

- 1 2 Neufeld, R.; Teuteberg, T. L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Mata, R. A.; Stalke, D. (2016). "Solution Structures of Hauser Base iPr2NMgCl and Turbo-Hauser Base iPr2NMgCl·LiCl in THF and the Influence of LiCl on the Schlenk-Equilibrium". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (14): 4796–4806. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b00345. PMID 27011251.

- ↑ Eaton, P. E.; Lee, C. H.; Xiong, Y. (1989). "Magnesium amide bases and amido-Grignards. 1. Ortho magnesiation". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (20): 8016–8018. doi:10.1021/ja00202a054.

- ↑ Shilai, M.; Kondo, Y.; Sakamoto, T. (2001). "Selective metallation of thiophene and thiazole rings with magnesium amide base". J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 (4): 442–444. doi:10.1039/B007376H.

- ↑ Kondo, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Sakamoto, T. (1996). "Magnesiation of indoles with magnesium amide bases". J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 (19): 2331–2332. doi:10.1039/P19960002331.

- ↑ "New Reagents for Selective Metalation, Deprotonation, and Additions | Sigma-Aldrich". Archived from the original on 2017-02-23. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ Tilly, D.; Chevallier, F.; Mongin, F.; Gros, P. C. (1996). "Bimetallic Combinations for Dehalogenative Metalation Involving Organic Compounds". Chem. Rev. 114 (2): 1207–1257. doi:10.1021/cr400367p. PMID 24187937.

- ↑ Klatt, T.; Markiewicz, J. T.; Sämann, C.; Knochel, P. (2014). "Strategies To Prepare and Use Functionalized Organometallic Reagents". J. Org. Chem. 79 (10): 4253–4269. doi:10.1021/jo500297r. PMID 24697240.