Health in Peru has changed drastically from pre-colonial times to the modern era. When European conquistadors invaded Peru, they brought with them diseases against which the Inca population had no acquired immunity. Much of the population died, and this marked an important turning point in the nature of Peruvian healthcare. Since Peru gained independence, the country's major healthcare concern has shifted to the disparity in care between the poor and non-poor, as well as between rural and urban populations. Another unique factor is the presence of indigenous health beliefs, which continue to be widespread in modern society.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[1] finds that Peru is fulfilling 85.6% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to health based on its level of income.[2] When looking at the right to health with respect to children, Peru achieves 97.0% of what is expected based on its current income.[2] In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves only 91.9% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income.[2] Peru falls into the "very bad" category when evaluating the right to reproductive health because the nation is fulfilling only 67.9% of what the nation is expected to achieve based on the resources (income) it has available.[2]

History

Before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the early 1500s, the population of the Inca Empire which covered five countries - Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, northern and central Chile, northwest Argentina - is estimated at between 9 million and 16 million people. The Andean people had been isolated for millennia and therefore had no reason to build up any sort of immunity against foreign diseases. This meant that the introduction of a non-native population had the potential to spell disaster for the Andeans. Even before Francisco Pizarro arrived on the coast of Peru, the Spaniards had spread diseases such as smallpox, malaria, typhus, influenza, and the common cold to the people of South America. Forty years after the arrival of European explorers and conquistadors, Peru's native population had decreased by about 80%. Population recovery was made almost impossible by the killer pandemics that occurred approximately every ten years. Additionally, the stress caused by war, exploitation, socioeconomic change, and psychological trauma caused by the conquests was enough to further weaken the indigenous people and render recovery impossible.[3]

Health in Peru today

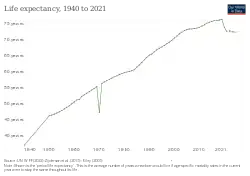

In many ways, health in Peru has been improving. In 2010, the World Health Organization collected data about the life expectancy of people living in Peru. It found that, on average, life expectancy for men at birth is 74 years, while for women it is 77. These values are higher than the global averages of 66 and 71 years, respectively.[4] The mortality rate of this population has been decreasing steadily since 1990 and now stands at 19 deaths per 1000 live births.[4] Regardless of this improvement, health in Peru still faces some challenges today. Marginalized groups, such as individuals living in rural areas and indigenous populations, are especially at risk for health related issues.

Healthcare system

Peru has a decentralized healthcare system that consists of a combination of governmental and non-governmental coverage. Health care is covered by the Ministry of Health, EsSalud, the Armed Forces (FFAA), and National Police (PNP), as well as private insurance companies. The Ministry of Health insures 60% of the population and EsSalud covers another 30%. The remaining population in Peru is insured by a combination of the FFAA, PNP, and private insurance companies.[5]

Current issues

- The risk of infectious disease in Peru is considered to be very high. Common ailments include waterborne bacterial diseases, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, dengue fever, malaria, yellow fever, and leptospirosis.[6]

- In the population under five years of age, common causes of death are congenital anomalies, prematurity, injuries, pneumonia, birth asphyxia, neonatal sepsis, diarrhea, and HIV/AIDS. The mortality rate of this population has been decreasing steadily since 1990 and now stands at 19 deaths per 1000 live births.[4]

- Demand for health workers in Peru has increased over time. The number of health workers per area is not evenly distributed, and many rural areas lack the amount of health workers they need. The country has been working to solve this problem by incentivizing health care providers to remain in rural areas, however this has yet to solve the issue[4]

- Climate change also has a significant impact on the quality of health in Peru today. Small changes in climate allow for the vectors that spread diseases like dengue and yellow fever to thrive.[7] Deforestation that contributes to climate change may also be a factor,[7] as it allows more carriers of pathogens to move between previously unaffected areas.

Indigenous health

Indigenous populations in Peru generally face worse health risks than other populations in the country. One source of this issue is access to health facilities. Health facilities are often a large distance away from indigenous communities and are difficult to access. Many indigenous communities within Peru are located in areas that have little land transportation. This hinders the indigenous population's ability to access care facilities. Distance along with financial constraints act as deterrents from seeking medical help. Furthermore, the Peruvian government has yet to devote significant amounts of resources to improving the quality and access to care in rural areas.[8]

Traditional medicine is widely used in indigenous populations and it is debated whether this is a factor in the quality of health in these communities. The indigenous groups of the Peruvian Amazon practice traditional medicine and healing at an especially high rate; Traditional medicine is more affordable and accessible than other alternatives[9] and has cultural significance. It has been argued that the use of traditional medicine may keep indigenous populations from seeking help for diseases such as tuberculosis,[8] however this has been disproven. While some indigenous individuals choose to practice traditional medicine before seeking help from a medical professional, this number is negligible and the use of traditional medicine does not seem to prevent indigenous groups seeking medical attention.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- 1 2 3 4 "Peru - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ↑ "History of Peru, The Colonial Period, 1550-1824". Motherearthtravel.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- 1 2 3 4 "WHO | Peru". Who.int. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "WHO | Peru". WHO. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- 1 2 Campbell-Lendrum, Diarmid; Manga, Lucien; Bagayoko, Magaran; Sommerfeld, Johannes (2015-04-05). "Climate change and vector-borne diseases: what are the implications for public health research and policy?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 370 (1665): 20130552. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0552. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4342958. PMID 25688013.

- 1 2 Brierley, Charlotte (2014). "Healthcare Access and Health Beliefs of the Indigenous Peoples in Remote Amazonian Peru" (PDF). The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 90 (1): 180–103. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0547. PMC 3886418. PMID 24277789 – via PubMed.

- ↑ Bussmann, Rainer (28 December 2013). "The Globalization of Traditional Medicine in Northern Peru: From Shamanism to Molecules". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 291903. doi:10.1155/2013/291903. PMC 3888705. PMID 24454490.

- ↑ Oeser, Clarissa (September 2005). "Does traditional medicine use hamper efforts at tuberculosis control in urban Peru?". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 73 (3): 571–575. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.571. PMID 16172483.