Heinz Strüning | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 January 1912 Neviges, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 24 December 1944 (aged 32) near Bergisch Gladbach, Free State of Prussia, Nazi Germany |

| Buried | cemetery Westönnen |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1935–44 |

| Rank | Hauptmann (captain) |

| Unit | ZG 26, KG 30, NJG 2, NJG 1 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves |

Heinz Strüning (13 January 1912 – 24 December 1944) was a German Luftwaffe military aviator during World War II, a night fighter ace credited with 56 nocturnal aerial victories claimed in 280 combat missions.[Note 1]

All of his victories were claimed over the Western Front in Defense of the Reich missions against the Royal Air Force's Bomber Command. He was shot down and killed in action on Christmas Eve, 24 December 1944.

Early life and career

Strüning was born on 13 January 1912 in Neviges, at the time in the Rhine Province of the German Empire. He was the son of electrician Karl Strüning. Following graduation from the Realgymnasium—a secondary school built on the mid-level Realschule—in Langenberg he began his vocational education as a merchant. In March 1935, he joined the Luftwaffe and was trained as a pilot.[1][Note 2]

Holding the rank of Unteroffizier, he was posted to 5. Staffel (5th squadron) of Zerstörergeschwader 26 "Horst Wessel" (ZG 26—26th Destroyer Wing), named after the Nazi martyr Horst Wessel, on 2 August 1939.[3][Note 3]

World War II

World War II in Europe began on Friday, 1 September 1939, when German forces invaded Poland. Flying with ZG 26, he flew several patrol missions on the Western Front during the Phoney War period. On 9 April 1940, the Wehrmacht launched Operation Weserübung, the German assault on Denmark and Norway. Two days later, Strüning was reassigned to the Zerstörrerstaffel of Kampfgeschwader 30 (KG 30—30th Bomber Wing). Until 9 June, he flew escort missions in support of the German troops at Narvik. For his service in Norway, he was awarded the Iron Cross second Class (Eisernes Kreuz zweiter Klasse) on 15 July 1940. On 1 August 1940, Strüning was promoted to Feldwebel (sergeant).[1]

Night fighter career

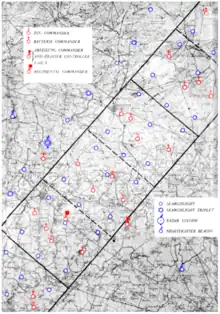

Following the 1939 aerial Battle of the Heligoland Bight, Royal Air Force (RAF) attacks shifted to the cover of darkness, initiating the Defence of the Reich campaign.[4] By mid-1940, Generalmajor (Brigadier General) Josef Kammhuber had established a night air defense system dubbed the Kammhuber Line. It consisted of a series of control sectors equipped with radars and searchlights and an associated night fighter. Each sector named a Himmelbett (canopy bed) would direct the night fighter into visual range with target bombers. In 1941, the Luftwaffe started equipping night fighters with airborne radar such as the Lichtenstein radar. This airborne radar did not come into general use until early 1942.[5]

In July 1940, elements of (Z)KG 30 were trained and converted to flying night fighter missions. These elements then became the 4. Staffel in the II. Gruppe (2nd group) of the newly created Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 (NJG 1—1st Night Fighter Wing). On 11 September, II. Gruppe of NJG 1 was reassigned and became the I. Gruppe of Nachtjagdgeschwader 2 (NJG 2—2nd Night Fighter Wing), subsequently Strünning became a pilot of 1./NJG 2.[1] Kammhuber had created I./NJG 2 with the idea of utilizing the Junkers Ju 88 C-2 and Dornier Do 17 Z as an offensive weapon, flying long range intruder (Fernnachtjagd) missions into British airspace, attacking RAF airfields. Until October 1941, I. Gruppe operated from the Gilze-Rijen Air Base.[6]

With this unit, Strüning flew 66 intruder missions over England at night,[7] and claimed his first aerial victory on the night of 23 November 1940 over a Vickers Wellington bomber 50 kilometres (31 miles) west of Scheveningen.[8][9] Two days later, he received the Iron Cross first Class (Eisernes Kreuz erster Klasse). For his service in Norway, he was presented the Narvik Shield on 30 January 1941.[1] On the evening of 15 February 1941, Strüning claimed a Lockheed Hudson 75 km (47 mi) east of Great Yarmouth and a Wellington 65 km (40 mi) east-northeast of Southend-on-Sea.[10] Following his fifth aerial victory, he received the Honour Goblet of the Luftwaffe (Ehrenpokal der Luftwaffe) on 12 June 1941. On 1 July 1941, Strüning was promoted to Oberfeldwebel (Master Sergeant).[1] He claimed his ninth and last intruder aerial victory on 13 October 1941 over a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress in the vicinity of Upwood over England.[11]

In the timeframe 24 October 1940, the date of I. Gruppe's first aerial victory, to 12 October 1941, the intruder Gruppe claimed approximately 100 RAF aircraft destroyed, additionally further aircraft were damaged as well as RAF ground targets attacked. This came at the expense of 26 aircraft lost. In October 1941, Hitler ordered the intruder operations stopped as he was skeptical of the results. The unit was then ordered to Catania, Sicily in the Mediterranean theater of operations.[12] Strüning however stayed at Gilze-Rijen and was transferred to the Ergänzungsjagdgruppe, a supplementary unit of NJG 2.[1]

In November 1941, he was transferred to 7./NJG 2. With this unit, Strüning gained 15 victories until mid-September 1942. He received the German Cross in Gold (Deutsches Kreuz in Gold) in July 1942, after his 19th claim. In mid September 1942 he was promoted to Leutnant and awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes) in October 1942. Strüning is then transferred to 2./NJG 1 in May 1943.

Staffelkapitän and death

Strüning was promoted to Oberleutnant (first lieutenant) on 1 August 1943.[13] On 15 August, he was then appointed Staffelkapitän of 3. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 (NJG 1—1st Night Fighter Wing). On 23 August 1943, Strüning claimed a Lancaster shot down 20 km (12 mi) east of Eindhoven.[14]

Strüning coordinated the introduction of the new Heinkel He 219 "Uhu". With this aircraft, Strüning downed three bombers on the night of 31 August 1943, a Halifax 20 kilometers (12 miles) west of Mönchengladbach.[15] On 22 June 1944, he shot down three RAF bombers. Strüning was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub) on 20 July 1944.

On 7 October, Helmut Lent, the Geschwaderkommodore of NJG 3, died of wounds sustained in a flying accident the day before. Lent's state funeral was held in the Reich Chancellery, Berlin, on Wednesday 11 October 1944. Strüning, together with Oberstleutnant Hans-Joachim Jabs, Major Rudolf Schoenert, Oberstleutnant Günther Radusch, Hauptmann Karl Hadeball and Hauptmann Paul Zorner, formed the guard of honor.[16] On 15 November, Strüning again participated in a guard of honor. He and Leutnant Karl Schnörrer, Oberst Gordon Gollob, Major Georg Christl, Major Rudolf Schoenert, Major Josef Fözö formed the guard of honor at Walter Nowotny funeral at the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna. Nowotny had been killed in action on 8 November 1944. The eulogy was delivered by Generaloberst Otto Deßloch.[17]

At about 6 pm on 24 December 1944 his Messerschmitt Bf 110 G-4 (Werknummer 740 162—factory number) G9+CT was shot down by 10-kill ace F/L R.D. Doleman and F/L D.C. Bunch of No. 157 Squadron RAF in a de Havilland Mosquito Intruder while he tried to attack a Lancaster bomber over Cologne.[18] He bailed out but struck the tail of his plane and fell to his death. His body was found two months after his death.[19] Strüning was buried at the Ostfriedhof (eastern cemetery) in Westönnen in field X, grave 14.[20]

Summary of career

Aerial victory claims

During his career, Hauptmann Heinz Strüning had made 280 combat missions (250 at night), and claimed 56 victories at night (including two Mosquitoes).

Foreman, Parry and Mathews, authors of Luftwaffe Night Fighter Claims 1939 – 1945, researched the German Federal Archives and found records for 56 nocturnal victory claims.[21] Mathews and Foreman also published Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims, listing Strüning with 56 aerial victories claimed in 280 combat missions.[22]

| Chronicle of aerial victories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claim | Date | Time | Type | Location | Serial No./Squadron No. |

| – 1. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 2 –[8] | |||||

| 1 | 23 November 1940 | 18:40 | Wellington | 50 km (31 mi) west of Scheveningen[23] | |

| 2 | 15 February 1941 | 09:15 | Hudson | 75 km (47 mi) east of Great Yarmouth[10] | |

| 3 | 15 February 1941 | 19:58 | Wellington | 65 km (40 mi) east-northeast of Southend-on-Sea[10] | |

| 4 | 7 May 1941 | 02:08 | Wellington | Peterborough[24] | Wellington R3227/No. 11 Operational Training Unit RAF[25] |

| 5 | 9 May 1941 | 23:30 | Wellington | over the North Sea[24] | |

| 6 | 5 July 1941 | 01:57 | Wellington | vicinity of Bircham Newton[26] | |

| 7 | 19 August 1941 | 01:20 | Blenheim | vicinity of Grantham[27] | |

| 8 | 19 August 1941 | 02:00 | Blenheim | vicinity of Grantham[27] | |

| 9 | 13 October 1941 | 22:20 | B-17 | vicinity of Upwood[11] | |

| – Ergänzungsjagdgruppe of Nachtjagdgeschwader 2 –[22] | |||||

| 10 | 26 January 1942 | 22:35 | Whitley[28] | ||

| 11 | 29 April 1942 | 01:15 | Boston | 5 km (3.1 mi) southeast of Noordschans[29] | |

| 12 | 9 May 1942 | 01:02 | Stirling[30] | ||

| 13 | 20 May 1942 | 00:56 | Stirling[30] | Stirling DJ977/No. 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron RAF[31] | |

| 14 | 31 May 1942 | 00:27 | Boston[32] | Manchester L7429/No.49 Conversion Flight RAF[33] | |

| 15 | 2 June 1942 | 03:10 | B-24[34] | ||

| 16 | 2 June 1942 | 03:25 | Wellington[34] | Stirling R9318/No. 15 Squadron RAF[35] | |

| 17 | 6 June 1942 | 03:35 | Stirling[36] | ||

| 18 | 20 June 1942 | 03:27 | Wellington[37] | ||

| 19 | 26 June 1942 | 01:13 | B-24[38] | ||

| – 8. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 2 –[39] | |||||

| 20 | 22 July 1942 | 01:45 | Halifax | 14 km (8.7 mi) south of Utrecht[40] | |

| 21 | 26 July 1942 | 02:30 | Wellington | northeast of Amersfoort[41] | |

| 22 | 30 July 1942 | 03:55 | Wellington[42] | ||

| 23 | 10 September 1942 | 22:50 | Wellington | 12 km (7.5 mi) northeast of Helmond[43] | |

| 24 | 16 September 1942 | 23:34 | Wellington[44] | Stirling DF550/No. 142 Squadron RAF[45] | |

| – 2. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 –[39] | |||||

| 25 | 14 May 1943 | 01:49 | Halifax | 10 km (6.2 mi) north of Breskens[46] | |

| 26 | 14 May 1943 | 02:26 | Halifax | 60 km (37 mi) west of Walcheren[46] | Halifax W7935/No. 102 Squadron RAF[47] |

| 27 | 24 May 1943 | 02:14 | Stirling | 18 km (11 mi) south of Utrecht[48] | Stirling BK783/No. 75 Squadron RAF[49] |

| 28 | 26 May 1943 | 02:33 | Wellington | Loosduinen[48] | Wellington HE228/No. 192 Squadron RAF[50] |

| 29 | 28 May 1943 | 01:54 | Mosquito | 15 km (9.3 mi) southeast of Gouda[51] | |

| 30 | 17 June 1943 | 02:06 | Halifax | 10 km (6.2 mi) northwest of Euddorp[52] | |

| 31 | 22 June 1943 | 02:02 | Lancaster[53] | Lancaster ED885/No. 156 Squadron RAF[54] | |

| 32 | 23 June 1943 | 02:39 | Halifax | 16 km (9.9 mi) east of Utrecht[53] | Halifax DT700/No. 77 Squadron RAF[55] |

| 33 | 25 June 1943 | 02:49 | Lancaster | 30 km (19 mi) west of Schouwen[56] | Lancaster LM327/No. 97 Squadron RAF[57] |

| 34 | 25 June 1943 | 02:56 | Halifax | 20 km (12 mi) west-northwest of Schouwen[56] | Halifax JD250/No. 51 Squadron RAF[58] |

| 35 | 25 June 1943 | 03:02 | Stirling | 25 km (16 mi) west of Schouwen[56] | Stirling BK628/No. 90 Squadron RAF[59] |

| – 3. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 –[39] | |||||

| 36 | 14 July 1943 | 01:40 | Halifax | Venlo railway station[60] | Halifax BB323/No. 419 Squadron RCAF[61] |

| 37 | 23 August 1943 | 01:43 | Lancaster | 20 km (12 mi) east of Eindhoven[14] | Lancaster ED701/No. 103 Squadron[62] |

| 38 | 31 August 1943 | 03:20 | Halifax | 20 km (12 mi) west of Mönchengladbach[15] | Halifax LK894/No. 434 (Bluenose) Squadron RCAF[63] |

| 39 | 31 August 1943 | 03:45 | Halifax | west of Mönchengladbach[15] | Stirling EH938/No. 75 Squadron RAF[64] |

| 40 | 31 August 1943 | 03:45 | Halifax | 60 km (37 mi) west-southwest of Mönchengladbach[15] | Halifax HR739/No. 158 Squadron RAF[65] |

| 41 | 1 September 1943 | 01:05 | Halifax | Brandenburg[66] | |

| 42 | 25 March 1944 | 00:30 | four-engined bomber | 230° from Dortmund[67] | Lancaster LM471/No. 576 Squadron RAF[68] |

| 43 | 11 May 1944 | 00:15 | Lancaster | 18 km (11 mi) northeast of Bruges[69] | Halifax LV985/No. 427 Squadron RCAF[70] |

| 44 | 13 May 1944 | 00:48 | Halifax | 15 km (9.3 mi) south-southeast of Brussels[69] | Halifax MZ629/No. 431 (Iroquois) Squadron RCAF[71] |

| 45 | 22 May 1944 | 01:32 | Lancaster | north of Fessenhout[72] | Lancaster LL951/No. 460 Squadron RAAF[73] |

| 46 | 23 May 1944 | 01:14 | Lancaster | vicinity of Giessen[74] | |

| 47 | 25 May 1944 | 00:47 | Halifax | vicinity of Leopoldsburg[75] | Halifax HX352/No. 429 Squadron RCAF[76] |

| 48 | 25 May 1944 | 01:15 | Viermot | Off Ostend[75] | |

| 49 | 3 June 1944 | 00:36 | Halifax | Schouwen Island[77] | |

| 50 | 6 June 1944 | 02:30 | Mosquito | Noord Brabant[77] | Mosquito NS950/No. 515 Squadron[78] |

| 51 | 17 June 1944 | 01:07 | four-engined bomber | beacon "Gorilla"[79][Note 4] | |

| 52 | 17 June 1944 | 01:13 | four-engined bomber | beacon "Gorilla"[79][Note 4] | |

| 53 | 22 June 1944 | 01:13 | Lancaster | Venlo[80] | |

| 54 | 22 June 1944 | 01:17 | B-17 | vicinity of Maastricht[80] | B-17 SR382/No. 214 Squadron RAF[81] |

| 55 | 22 June 1944 | 02:30 | four-engined bomber | beacon "Hamster"[82][Note 5] | |

| 56 | 19 July 1944 | 01:55 | Mosquito | 50 km (31 mi) west of Berlin[83] | Mosquito MM136/No. 571 Squadron RAF[84] |

Awards

- Iron Cross (1939)

- Narvik Shield (30 January 1941)[1]

- Honour Goblet of the Luftwaffe (Ehrenpokal der Luftwaffe) on 12 June 1941 as Feldwebel in a Nachtjagdgeschwader[86]

- German Cross in Gold on 10 July 1942 as Oberfeldwebel in the Ergänzungsstaffel/Nachtjagdgeschwader 2[87]

- Wound Badge in Black (10 September 1943)[13]

- Front Flying Clasp of the Luftwaffe for Night Fighter in Gold with Pennant (31 May 1944)[13]

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves

Dates of rank

| 1 August 1940: | Feldwebel (Technical Sergeant)[1] |

| 1 July 1941: | Oberfeldwebel (Master Sergeant)[1] |

| 1 August 1942: | Leutnant (Second Lieutenant)[1] |

| 1 August 1943: | Oberleutnant (First Lieutenant)[13] |

| 1 April 1944: | Hauptmann (Captain)[13] |

Notes

- ↑ For a list of Luftwaffe night fighter aces see List of German World War II night fighter aces.

- ↑ Flight training in the Luftwaffe progressed through the levels A1, A2 and B1, B2, referred to as A/B flight training. A training included theoretical and practical training in aerobatics, navigation, long-distance flights and dead-stick landings. The B courses included high-altitude flights, instrument flights, night landings and training to handle the aircraft in difficult situations. For pilots destined to fly multi-engine aircraft, the training was completed with the Luftwaffe Advanced Pilot's Certificate (Erweiterter Luftwaffen-Flugzeugführerschein), also known as the C-Certificate.[2]

- ↑ For an explanation of the meaning of Luftwaffe unit designation see Organisation of the Luftwaffe during World War II.

- 1 2 Beacon "Gorilla"—At Schoonrewoerd in 51°55′N 5°6′E / 51.917°N 5.100°E

- ↑ Beacon "Hamster"—At Oostkapelle/Domburg in 51°35′N 3°32′E / 51.583°N 3.533°E

- ↑ According to Scherzer as Leutnant (war officer) and pilot in the 8./Nachtjagdgeschwader 2.[89]

- ↑ According to Scherzer as Hauptmann (war officer).[89]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Stockert 2012, p. 105.

- ↑ Bergström, Antipov & Sundin 2003, p. 17.

- ↑ MacLean 2007, p. 441.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 9.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ Hinchliffe 1998, p. 39.

- ↑ Obermaier 1989, p. 67.

- 1 2 Mathews & Foreman 2015, p. 1289.

- ↑ Forsyth 2019, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 16.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 32.

- ↑ Hinchliffe 1998, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stockert 2012, p. 106.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 4 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 108.

- ↑ Hinchliffe 2003, pp. 266–267.

- ↑ Held 1998, p. 157.

- ↑ Thomas & Davey 2005, p. 72.

- ↑ Bowman 2020, p. 352.

- ↑ Stockert 2012, p. 107.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, pp. 12–202.

- 1 2 Mathews & Foreman 2015, pp. 1289–1290.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 12.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Wellington R3227.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 24.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 29.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 39.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 40.

- ↑ Stirling DJ977.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ Manchester L7429.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 43.

- ↑ Stirling R9318.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 46.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Mathews & Foreman 2015, p. 1290.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 50.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 58.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 59.

- ↑ Stirling DF550.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 80.

- ↑ Halifax W7935.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ Stirling BK783.

- ↑ Wellington HE228.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 83.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 87.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 88.

- ↑ Lancaster ED885.

- ↑ Halifax DT700.

- 1 2 3 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 90.

- ↑ Lancaster LM327.

- ↑ Halifax JD250.

- ↑ Stirling BK628.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 93.

- ↑ Halifax BB323.

- ↑ Lancaster ED701.

- ↑ Halifax LK894.

- ↑ Stirling EH938.

- ↑ Halifax HR739.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 110.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 159.

- ↑ Lancaster LM471.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 176.

- ↑ Halifax LV985.

- ↑ Halifax MZ629.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 177.

- ↑ Lancaster LL951.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 178.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 179.

- ↑ Halifax HX352.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 181.

- ↑ Mosquito NS950.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 188.

- 1 2 Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 190.

- ↑ Bowman 2016, p. 104.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 191.

- ↑ Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 202.

- ↑ Mosquito MM136.

- 1 2 Thomas 1998, p. 365.

- ↑ Patzwall 2008, p. 201.

- ↑ Patzwall & Scherzer 2001, p. 466.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 415.

- 1 2 Scherzer 2007, p. 732.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 85.

Bibliography

- Bergström, Christer [in Swedish]; Antipov, Vlad; Sundin, Claes (2003). Graf & Grislawski – A Pair of Aces. Hamilton MT: Eagle Editions. ISBN 978-0-9721060-4-7.

- Bowman, Martin (2016). German Night Fighters Versus Bomber Command 1943–1945. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-1-4738-4979-2.

- Bowman, Martin (2020). Battle of Berlin: Bomber Command over the Third Reich, 1943–1945. Air Worlds. ISBN 978-1-5267-8638-8.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer [in German] (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Forsyth, Robert (2019). Ju 88 Aces of World War 2. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-2922-1.

- Foreman, John; Parry, Simon; Mathews, Johannes (2004). Luftwaffe Night Fighter Claims 1939–1945. Walton on Thames: Red Kite. ISBN 978-0-9538061-4-0.

- Held, Werner (1998). Der Jagdflieger Walter Nowotny Bilder und Dokumente [The Fighter Pilot Walter Nowotny Images and Documents] (in German). Stuttgart, Germany: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-87943-979-9.

- Hinchliffe, Peter (1998). Luftkrieg bei Nacht 1939–1945 [Air War at Night 1939–1945] (in German). Stuttgart, Germany: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-613-01861-7.

- Hinchliffe, Peter (2003). "The Lent Papers" Helmut Lent. Bristol, UK: Cerberus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84145-105-3.

- MacLean, French L (2007). Luftwaffe Efficiency & Promotion Reports: For the Knight's Cross Winners. Vol. Two. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History. ISBN 978-0-7643-2658-5.

- Mathews, Andrew Johannes; Foreman, John (2015). Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims — Volume 4 S–Z. Walton on Thames: Red Kite. ISBN 978-1-906592-21-9.

- Obermaier, Ernst (1989). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Luftwaffe Jagdflieger 1939 – 1945 [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the Luftwaffe Fighter Force 1939 – 1945] (in German). Mainz, Germany: Verlag Dieter Hoffmann. ISBN 978-3-87341-065-7.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941 – 1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941 – 1945 History and Recipients Volume 2] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Patzwall, Klaus D. (2008). Der Ehrenpokal für besondere Leistung im Luftkrieg [The Honor Goblet for Outstanding Achievement in the Air War] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-08-3.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Militaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Stockert, Peter (2012). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 6 [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 6] (in German) (3rd ed.). Bad Friedrichshall, Germany: Friedrichshaller Rundblick. OCLC 76072662.

- Thomas, Andrew; Davey, Chris (2005). Mosquito Aces of World War 2. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-878-2.

- Thomas, Franz (1998). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 2: L–Z [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 2: L–Z] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2300-9.

- Accident description for Halifax BB323 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax DT700 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax HR739 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax HX352 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax JD250 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax LK894 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax LV985 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax MZ629 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Halifax W7935 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Lancaster ED701 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Lancaster ED885 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Lancaster LL951 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Lancaster LM327 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Lancaster LM471 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Manchester L7429 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Mosquito MM136 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Mosquito NS950 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Stirling BK628 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Stirling BK783 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Stirling DF550 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Stirling DJ977 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Stirling EH938 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 26 September 2022.

- Accident description for Stirling R9318 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Wellington HE228 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- Accident description for Wellington R3227 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.