| Henry Clay Frick House | |

|---|---|

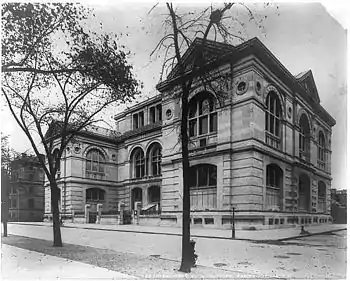

.jpg.webp) The main facade on Fifth Avenue | |

| General information | |

| Type | Mansion |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| Address | 1 East 70th Street |

| Town or city | New York, NY 10021 |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 40°46′17″N 73°58′02″W / 40.7713°N 73.9673°W |

| Current tenants | Frick Collection |

| Construction started | 1912 |

| Completed | 1914 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Thomas Hastings |

Henry Clay Frick House | |

Location in New York City  Henry Clay Frick House (New York)  Henry Clay Frick House (the United States) | |

| Coordinates | 40°46′17″N 73°58′02″W / 40.7713°N 73.9673°W |

| Area | 1.26 acres (0.51 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 08001091 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 6, 2008[1] |

| Designated NHL | October 6, 2008[2] |

| Designated NYCL | March 20, 1973[3] |

| References | |

| [4] | |

The Henry Clay Frick House was the residence of the industrialist and art patron Henry Clay Frick in New York City. The mansion is located between 70th and 71st Street and Fifth Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. It was constructed in 1912–1914 by Thomas Hastings of Carrère and Hastings. It was transformed into a museum in the mid-1930s and houses the Frick Collection and the Frick Art Reference Library. The house and library were designated a National Historic Landmark in 2008 for their significance in the arts and architecture as a major repository of a Gilded Age art collection.[5]

History

After Frick's business partnership with Andrew Carnegie started breaking apart, he began spending less time in Pittsburgh, and soon established additional residences in New York and Massachusetts. In 1905, Frick leased the William H. Vanderbilt House at 640 Fifth Avenue. He and his family stayed there for the next nine years.[6] At that time almost every building on Fifth Avenue above 59th Street was a private mansion, with a few private clubs and a hotel. The Andrew Carnegie Mansion was also located on Fifth Avenue at 91st Street. Whether Frick decided to establish himself on the same avenue because of Carnegie is not definitely established.[7][8] He started looking for a permanent place to set up residence and became interested in the plot on Fifth Avenue between 70th and 71st Street, that was the site of the Lenox Library. The building housed the private collection of philanthropist James Lenox and was designed by the New York architect Richard Morris Hunt in the neo-Greek style.[9]

The library was suffering financially, which enabled Frick to acquire the plot in the summer of 1906 for $2.47 million.[10] Four months later, he added an additional parcel of land running some fifty feet east through the block. Due to restrictions placed on the use of the library site, Frick could not take title of the land until 1912, when the Lenox collections were incorporated and moved into the New York Public Library's new Main Branch at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. The library building was subsequently torn down that year.[6]

Initially Frick sought designs from Daniel Burnham, who was the architect of the Frick Building in downtown Pittsburgh. Burnham submitted a design for an 18th-century Italian palazzo.[10] Ultimately he commissioned architect Thomas Hastings of the firm Carrère and Hastings to design and build his residence.[6] Hastings designed a three-story mansion in the Beaux-Arts architecture. Construction took place between 1912 and 1914. The material used for the exterior and parts of the interior of the mansion is Indiana limestone.[11]

Frick, along with his wife Adelaide Howard Childs (1859–1931) and daughter Helen Clay Frick (1888–1984), moved in during November 1914. The interior was not completed until 1916 and the large art collection moved in. His son Childs Frick (1883–1965) had married Frances Shoemaker Dixon in late 1913, and consequently never resided in the house.[6]

At Frick's death in 1919, he left his house and all of its contents, including art, furniture, and decorative objects, as a museum to the public. His family continued to live in the house until his wife died. Some of the earliest photographic documentation of the interior was taken in 1927 by Frick Art Reference Library photographer Ira W. Martin. Four years after these photographs were taken, on the death of Adelaide Frick, the trustees of the collection began the transformation of the house into a museum. The collection opened to the public in 1935.[12]

Around one-third of the pictures of the collection have been acquired since Frick's death. The building itself has been enlarged three times, in 1931–35, 1977 and 2011, which has altered the original appearance of the house.[13] John Russell Pope converted the former courtyard into the enclosed garden court[14] and demolished the porte-cochère to make way for a public entryway, now known as the entrance hall.[15] Frick's office on the ground floor was also demolished to make way for the oval room. The east gallery and the music room are also later additions.

Architecture

The house is set apart from Fifth Avenue by an elevated garden on the Fifth Avenue side that has three magnolia trees.[13] The house featured an interior courtyard.

The entrance for visitors is located on 70th Street. The entrance hall has stone walls which are marble-lined and a ceiling carved by the Piccirilli Brothers. The marble staircase with an intricate wrought metal balustrade leads to the second floor, which was private. The first room on the ground floor is the Fragonard room, named for Jean-Honoré Fragonard's large wall paintings. The room is furnished with 18th-century French furniture and Sèvres porcelain. The following room is the living room with the adjacent panelled Georgian architecture library. The west gallery, where some of the most important paintings were hung, is 100 feet long. Next to it is the enamels room.[13] Adjacent to the west gallery was Frick's office, which faced the courtyard. The British decorator Charles Allom of White, Allom & Co. was selected to furnish the rooms on the ground floor.[6][16] The manufacturer A. H. Davenport and Company provided furniture and interior woodwork, fabrics, wall coverings and decorative paintings.[17]

With the exception of the Fragonard room, the house remained essentially unchanged from the time of its construction until 1931, the year Adelaide Frick died.[6]

The second floor were the private apartments of the family, such as the bedrooms, the women's boudoir, sitting rooms, the breakfast room and guest rooms.[18][19] Charles Allom also furnished some rooms on the second floor, including the breakfast room and Frick's personal sitting room. The remaining rooms on the second were decorated by Elsie de Wolfe, who was also commissioned to furnish the ladies' reception room on the first floor, which is now the Boucher room of the museum.[6]

The rooms of the third floor were the servants quarters, which were occupied by around 27 servants.[18] These were also decorated by Elsie de Wolfe.[6] The second and third floors are now used by the museum staff and are not normally accessible to the general public.[19]

The large basement was where the kitchen and service areas were located. A wing contained the billiard room and bowling alley.[19][20] These spaces were decorated in the Jacobean style with ornate strapwork ceilings. During the 1920s and early 1930s, the Frick Art Reference Library was housed here until they moved to a new structure next door at 10 East 71st Street.[21]

In popular culture

According to Stan Lee, who co-created the superhero team Avengers, the house was the model for the Avengers Mansion.[22][23]

See also

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ↑ "The Frick Collection and Frick Art Reference Library Building". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Henry Clay and Adelaide Childs Frick House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 20, 1973. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ↑ "Emporis building ID 397992". Emporis.

- ↑ "NHL nomination for Frick Collection and Frick Art Reference Library Building". National Park Service. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Finding Aid for the Henry Clay Frick Furnishings Files, 1913-1920 TFC.0100.020". The Frick Collection. November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ↑ Kathrens, Michael C. (2005). Great Houses of New York, 1880-1930. New York: Acanthus Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-926494-34-3.

- ↑ Hoyt, Austin (August 15, 2004). "Andrew Carnegie: Program transcript". American Experience. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ↑ Harry Miller Lydenberg (September 1916). "History of the New York Public Library: Part III". Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 20 (9): 685–689.

- 1 2 Kathrens, Michael C. (2005). Great Houses of New York, 1880-1930. New York: Acanthus Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-926494-34-3.

- ↑ "Building the House". The Frick Collection. November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Henry Clay Frick: The New York Residence". The Frick Collection. November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "History". The Frick Collection. November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Garden Court". The Frick Collection. November 10, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Entrance Hall". The Frick Collection. December 16, 1935. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ↑ Morrone, Francis (December 8, 2006). "The House That Frick Built". The New York Sun. New York. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series IV: Receipts, File 1.18". The Frick Collection. November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- 1 2 "Building the House". The Frick Collection. November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "The Frick". New York Social Diary. November 30, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ↑ Bindelglass, Evan (February 14, 2013). "The Frick Collection Bowling Alley". Inaccessible New York. New York. Event occurs at 8:30. CBS. CBS New York. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ↑ Kathrens, Michael C. (2005). Great Houses of New York, 1880-1930. New York: Acanthus Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-926494-34-3.

- ↑ Hermann, Molly (August 15, 2004). Marvel Superheroes Guide To New York City (Television production). Discovery Channel. Event occurs at 11:48-13:12. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

There was a mansion called the Frick Museum that I used to walk past. I sort of modeled it after that. Beautiful, big, so impressive building, right on Fifth Avenue.

- ↑ Sanderson, Peter (2007). The Marvel Comics Guide to New York City. New York: Gallery Books. ISBN 978-1416531418.

Further reading

- Bailey, Colin B. (2006). Building the Frick Collection: An Introduction to the House and its Collections (PDF). New York: Frick Collection, in association with Scala Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 1-85759-381-2. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Frick Symington Sanger, Martha; Garrett, Wendell (2011). The Henry Clay Frick Houses: Architecture, Interiors, Landscapes in the Golden Era. The Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1580931045.

- Kathrens, Michael C. (2005). Great Houses of New York, 1880-1930. New York: Acanthus Press. pp. 269–276. ISBN 978-0-926494-34-3.

- Ossman, Laurie; Ewing, Heather (2011). Carrère and Hastings, The Masterworks. Rizzoli USA. ISBN 9780847835645.

External links

- "The Frick Collection museum view". Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved November 11, 2013.