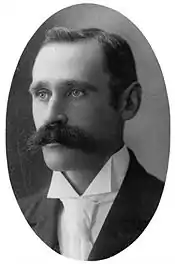

Henry Daglish | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th Premier of Western Australia | |

| In office 10 August 1904 – 25 August 1905 | |

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Governor | Sir Frederick Bedford |

| Preceded by | Sir Walter James |

| Succeeded by | Hector Rason |

| Colonial Treasurer | |

| In office 10 August 1904 – 25 August 1905 | |

| Premier | Himself |

| Preceded by | Hector Rason |

| Succeeded by | Hector Rason |

| Minister for Education | |

| In office 10 August 1904 – 7 June 1905 | |

| Premier | Himself |

| Preceded by | Walter Kingsmill |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Bath |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 25 August 1905 – 27 September 1905 | |

| Premier | Hector Rason |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | William Johnson |

| Leader of the Labor Party in Western Australia | |

| In office 8 July 1904 – 27 September 1905 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Hastie |

| Succeeded by | William Johnson |

| Minister for Works | |

| In office 16 September 1910 – 3 October 1911 | |

| Premier | Frank Wilson |

| Preceded by | Frank Wilson |

| Succeeded by | William Johnson |

| Member of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly for Subiaco | |

| In office 24 April 1901 – 3 October 1911 | |

| Preceded by | New seat |

| Succeeded by | Bartholomew James Stubbs |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 November 1866 Ballarat, Victoria, British Empire |

| Died | 16 August 1920 (aged 53) Subiaco, Western Australia, Australia |

| Resting place | Karrakatta Cemetery |

| Nationality | British subject |

| Political party | Labor (1901–1905)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Other political affiliations | Independent Labour (1905–1908) Liberal (1908–1911)[lower-alpha 2] |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent(s) | William Daglish Mary Ann (née James) |

| Alma mater | University of Melbourne |

| Occupation | Mechanical engineer, public servant, trade union official, real estate agent[1] |

Henry Daglish (18 November 1866 – 16 August 1920) was an Australian politician who was the sixth premier of Western Australia and the first from the Labor Party,[lower-alpha 1] serving from 10 August 1904 to 25 August 1905. Daglish was born in Ballarat, Victoria, and studied at the University of Melbourne. In 1882, he worked as a mechanical engineer but soon switched to working in the Victorian public service. He first stood for election in 1896 but failed to win the Victorian Legislative Assembly seat of Melbourne South. He then moved to Subiaco, Western Australia, where he found work as a chief clerk in the Western Australian Police Department. In 1900, Daglish was elected to the Subiaco Municipal Council and in April the following year, he was elected to the Western Australian Legislative Assembly as the member for the newly created seat of Subiaco, becoming one of six Labor members in the Western Australian Legislative Assembly. The party elected him as its whip, and he resigned from the Subiaco council on 1 May 1901. On 1 December 1902, Daglish was sworn in as mayor of Subiaco, having been elected the previous month.

In the 1904 state election, Labor won 22 of the Legislative Assembly's 50 seats, making it the party with the most seats. On 8 July 1904, the Labor Party caucus elected Daglish as the party's leader, and on 10 August, he successfully moved a motion of no confidence in the government of Walter James, who resigned as premier. Governor Frederick Bedford then swore in Daglish as premier of Western Australia, colonial treasurer and minister for education. His keynote speech on 23 August was poorly received; militant Labor supporters saw him as giving up on Labor policies. In parliament, Daglish struggled to achieve anything due to a hostile Legislative Council; his one major success was the passing of a new Public Service Act. In June 1905, a cabinet reshuffle decreased Daglish's popularity within the Labor Party but he defeated a motion of no confidence at a caucus meeting later that month. Daglish resigned as premier on 22 August 1905 when his plan to buy the Midland Railway Company for £1.5 million (equivalent to AU$126,500,000 in 2022) failed to pass through parliament. Hector Rason succeeded him as premier on 25 August.

On 27 September 1905, Daglish resigned as leader of the Labor Party. He then left the party and styled himself as an Independent Labor politician. He was again elected Mayor of Subiaco on 5 June 1907 and served until 1908. From August 1907 to September 1910, Daglish held the position of Chairman of Committees, and from September 1910 to October 1911, he was the minister for works in Frank Wilson's Liberal[lower-alpha 2] government. At the October 1911 state election, Daglish lost his seat in parliament to Labor candidate Bartholomew James Stubbs and failed to regain the seat at the 1914 state election. Daglish died at his home in Subiaco on 16 August 1920. Daglish railway station and the suburb of Daglish, Western Australia, are named after him.

Early life

Henry Daglish was born in Ballarat, Victoria, on 18 November 1866, to Mary Ann (née James) and William Daglish, an engine driver. He was educated in Geelong and in 1881 he attended the University of Melbourne. He gained a mechanical engineering apprenticeship at a foundry in 1882[5][1][6] but a year later, he left engineering to join the public service as a clerk in the Victorian Police Department.[5][1][7]

On 20 August 1894, in Carlton, Victoria, Daglish married Edith May Bishop, with whom he had one son and one daughter.[5][1] With an increasing interest in the labour movement, by June 1895, Daglish was the secretary of the United Public Service Association. In September 1895, he went into business[5][1] as an auctioneer, accountant and legal manager.[8]

In 1895 and 1896, Daglish was a member of the National Anti-Sweating League, a group campaigning against the poor conditions endured by low-paid workers.[9][10] In 1896, Daglish stood in a by-election for the seat of Melbourne South in the Victorian Legislative Assembly, receiving 34 out of 2,192 total votes.[7][11] Later the same year, Daglish moved to Western Australia (WA) after taking an offer of £200 (equivalent to AU$17,900 in 2022) to resign from the recession-hit Victorian public service; he settled in the working-class suburb Subiaco, 4 km (2.5 mi) west of Perth, the state capital.[12]: 116 Daglish wrote a letter to Premier John Forrest requesting work in the WA public service in 1897; he was offered and accepted a position as assistant to the chief clerk in the WA Police Department.[5][1][7] He later resigned and entered business as an auctioneer, accountant and legal manager.[5][7]

Political career

In November 1899, Daglish unsuccessfully stood for election to the Central Ward of the Subiaco Municipal Council.[13] The following year, he was elected unopposed to the council's South Ward,[14] his term starting on 1 December 1900.[5]

Daglish resigned from the public service in 1901 to stand as a Labor Party[lower-alpha 1] candidate in the newly created seat of Subiaco in the Western Australian Legislative Assembly.[1][6] In the 1901 Western Australian state election on 24 April, Daglish was elected to that seat with the largest majority in the state, and became the whip of the Labor Party. The party had only seven members, all of whom, aside from Daglish, represented seats in the mining regions of Murchison and the Goldfields.[15] He tendered his resignation from the Subiaco Municipal Council on 1 May 1901.[16]

One of Daglish's successes in his first term is the carrying of his motion in favour of an eight-hour working day for the Railway Department.[9][10] He was also successful in stopping the spending of money to help public servants immigrate from England, instead spending the money on assisting Western Australian workers migrate their families from the eastern states. He also advocated for the non-alienation of crown lands and the introduction of a comprehensive system of old age pensions.[9]

In November 1902, Daglish was elected unopposed as mayor of Subiaco.[17] He was sworn in on 1 December 1902 by Walter James, the premier of Western Australia. The premier had earlier made a speech heaping much praise on Daglish.[18] He was again elected mayor unopposed the following year.[19]

Daglish was appointed to the Kings Park Board in his capacity as the member for Subiaco in October 1902.[20] In January 1903, Daglish joined the Perth Hospital Board, which managed Perth Public Hospital (now known as Royal Perth Hospital).[21] On the board, he "earned a reputation for shouldering the real or fancied troubles of dissatisfied ex-patients".[9] He was also a member of the Lake Monger Board and the Karrakatta Cemetery Board.[9]

In February 1904, the Labor Party held a conference at which they decided on the issues of their campaigning and platforms they would take to the next election. The issues were:[22][23]

- Referendum on abolishing the Legislative Council

- A tax on unimproved land values and no further alienation of crown lands

- Old age pensions

- Maximum working day of eight hours

- Local control and state management of the liquor trade

- Departmental construction of public works

- Nationalisation of monopolies and the establishment of a Department of Labour

- State banking and insurance

- Limitation on state borrowing except for the purpose of reproductive works

- The establishment of a sinking fund for the redemption of all future loans

In the general campaign were policies of electoral, taxation, land, industrial and mining reform.[22][23]

Premier of Western Australia

The Labor Party supported all but two pieces of the government's legislation during the fourth parliament.[24] Despite this, they withdrew support for the James Ministry in August 1903.[1] At the July 1904 state election, Daglish was re-elected with 80% of Subiaco's vote.[25] The Labor Party won 22 seats, James's Ministerialist faction won 18 seats, and independents won 10 seats.[26] The number of seats Labor won surprised most people, many of whom expected only a modest increase over the seven seats won in 1901.[27] Two bills that passed in the previous session of parliament helped Labor; the Redistribution of Seats Act 1904 created new electorates in areas where Labor did well,[28] and the Electoral Act 1904 abolished plural voting for property owners and made it easier for newcomers to Western Australia to qualify for the electoral roll.[29][30]

Labor leader Robert Hastie said James should not resign until parliament met,[31] and so James continued as premier following the election.[1] On 8 July 1904, the Labor Party caucus elected Daglish as the party's leader. Labor leader Hastie was universally hated and the leadership ballot was initially going to be between Hastie, Daglish, George Taylor, Patrick Lynch, Wallace Nelson and Henry Ellis. Hastie pulled out of the contest, and only Daglish and Taylor were left. Newspapers reported the vote was almost unanimously for Daglish.[32][33] The party decided to sit in opposition and not try and seek government because the caucus had been divided on whether to align with independents sympathetic for the party's cause.[34][35] When Daglish was elected Labor leader, the Sunday Figaro, a newspaper in Kalgoorlie, said he was "certainly one of the best debaters in the Legislative Assembly. He is a quiet, deliberate speaker, given more to argument than declamation, bearing in this respect a likeness to [Prime Minister Chris Watson]".[10]

On 10 August, Daglish successfully moved a motion of no confidence and James resigned as premier. Governor Frederick Bedford then swore in Daglish as premier of Western Australia, colonial treasurer and minister for education.[36] He was the first Labor Party premier of WA,[7] the sixth overall, and at 37 years of age, the youngest premier of the state at the time and the fourth-youngest as of 2022.[37] Daglish's Cabinet were sworn in the same day; his party granted him the freedom to choose his own cabinet.[36] Due to constitutional requirements that at least one minister be from the Legislative Council, Daglish invited John Drew, an unaligned politician, into the ministry, resulting in criticism from within his own party.[38] Despite becoming premier, Daglish did not move from Subiaco to a more affluent area as many other premiers had.[12]: 116 Immediate problems for Daglish were the state's poor financial situation and an inexperienced cabinet made up of unions that were hostile to each other.[1]

At Kings Hall, Subiaco, on 23 August, Daglish delivered a speech that was poorly received; militant Labor supporters saw him as giving up on Labor policies. He said the state's finances were in a poor position and expenditure was to be reduced. Newspapers mocked his use of the phrase "mark time policy" and so his government became known as the "mark time government".[1][39] In the same speech, Daglish proposed a referendum on abolishing the Legislative Council, a bill to introduce pensions for those over 60 years and who had lived in the state for 10 years, the introduction of land tax with exemptions for properties valued below £1,000 (equivalent to $88,000 in 2022) with the land value determined by the owner), the granting of greater job security for public servants, the establishment of a Department of Labor for the administration of workplace relations legislation, the amendment of the Truck Act, and companies and mining legislation to prevent monopolies and ensure all companies conducting business in Western Australia would have at least two local directors. Concerns with Daglish's speech included his lack of a clear policy for unemployment and that the tax exemption for land worth below £1,000 was a "violation of the Labor platform".[39][40] A few days later, Daglish said; "we have never, as a Labor Party advocated the abolition of the Legislative Council".[41]

The Legislative Council prevented much of Daglish's agenda; his government's one major change was the passing of a new Public Service Act.[1] He twice introduced a bill for a referendum to abolish the Legislative Council; the first bill was discharged at the end of the session[42] and the second failed to pass before the Daglish government resigned.[43] Daglish did not contest the November 1904 Subiaco municipal election; he was succeeded as mayor by John Henry Prowse.[44]

Daglish reshuffled his cabinet on 7 June 1905, making Thomas Bath the minister for education, leaving himself as premier and colonial treasurer. Patrick Lynch was added to cabinet, and George Taylor and John Holman were clumsily demoted. The cabinet reshuffle caused a split in the Labor Party; Daglish's opponents said he acted towards his colleagues in a high-handed and humiliating manner.[45][46] On 18 June, The Sunday Times wrote; "it has taken the Labor Party in politics – and in Parliament – nearly a year to find out that its leader is not in every particular, fully qualified to hold responsible office".[47] At a meeting of the Labor caucus on 26 June, Daglish defeated a motion of no confidence 14–3.[48]

After this, the government created a plan to buy the Midland Railway Company for £1.5 million (equivalent to $126,500,000 in 2022). The company owned the Midland railway line, which ran from Midland Junction near Perth to Walkaway near Geraldton. Opponents criticised the price for being too high, and Daglish failed to get approval from parliament on 17 August.[1] On Monday 22 August, the Daglish Ministry resigned; the state's governor gave the Liberal[lower-alpha 2]-aligned Hector Rason until the end of the week to form a cabinet.[49] On 25 August, the governor accepted the resignations of Daglish and his ministry, and appointed Hector Rason and the Rason Ministry to replace them.[50]

After premier

On 27 September 1905, Daglish resigned as leader of the Labor Party[51] and on 4 October, William Johnson was elected leader of the party.[52] Daglish later left the party[53] and began styling himself as an Independent Labor politician.[5][1] On 4 October, Rason moved for the discharge of the referendum bill; the motion was defeated 18 votes to 16 and the following day, the premier met with the governor to dissolve the Legislative Assembly.[43][54] The resulting election was called for 27 October. Labor Party lost eight seats at the election but Daglish narrowly retained his seat.[1] The failure of Daglish's government caused the Labor Party to be more careful in selecting candidates and to use more discipline.[55]

On 5 June 1907, Daglish was again elected Mayor of Subiaco,[56] following the resignation of the previous mayor Austin Bastow.[57] Daglish was sworn in on 12 June 1907.[58] He was re-elected unopposed in November 1907[59] and did not re-contest the post in 1908.[60]

From 20 August 1907 to 16 September 1910, Daglish held the position of Chairman of Committees. From 16 September 1910 to 3 October 1911, he was the minister for works in Frank Wilson's Liberal[lower-alpha 2] government.[5][6] At the October 1911 state election, Daglish lost his seat in parliament to Labor candidate Bartholomew James Stubbs. At the following election in 1914, Daglish unsuccessfully stood for the seat of Subiaco.[5]

Outside politics

From c. 1902 to 1906, Daglish was president of Subiaco Football Club.[61][62] During 1906, he helped hold off a campaign by North Fremantle Football Club for Subiaco's expulsion from the Western Australian Football Association after several years of poor performance. The club had been playing next to Shenton Park Lake, and the club's ground was wet and muddy. Daglish helped secure money from the Municipality of Subiaco for the construction of a playing ground at Mueller Park, which later became known as Subiaco Oval.[63][64][65][66] The club relocated there in 1908.[62] In 1911, Daglish again served as president of Subiaco Football Club.[61][62] From 1912, Daglish worked as an estate agent and from March that year, he was appointed the employers' representative in the Court of Arbitration, a post in which served until his death.[5][1][6]

Death and legacy

In 1920, Daglish, who had been ill for several months, travelled to Melbourne for medical treatment. In Melbourne, he had an operation and was diagnosed with cancer.[67] Daglish returned to Perth, arriving on 12 August 1920, and died at his home in Subiaco four days later.[1][6] He was buried at Karrakatta Cemetery.[1] He was survived by his wife Edith, who died aged 71 on 28 May 1946, and his two children.[68][69]

Although the Daglish government was little-remembered decades later, the Labor Party's coming to power marked the start of two-party politics in Western Australia. Labor came to be seen as the alternative to the Ministerialists, also known as Liberals.[70][4] When Daglish resigned, he became Western Australia's first leader of the opposition.[37]

Daglish railway station, which opened in 1924 on the western edge of Subiaco, was named after Henry Daglish.[71][72]: 32 The Perth suburb Daglish, adjacent to the railway station, was also named after him. The Subiaco house in which Daglish lived in from 1908 is heritage listed.[73]

See also

- Daglish Ministry

- Imprisonment of John Drayton, which occurred while Daglish was premier

- Electoral results for the district of Subiaco

Notes

- 1 2 3 Spelled as either "Labor" or "Labour" in the early 20th century. Originally called the Australian Labor Federation (WA), it was renamed to the Australian Labor Party in 1918.[2][3]

- 1 2 3 4 Also known as the Ministerialists, the Liberals were only a grouping within Parliament and were not a party until 1911[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Gibbney, H. J. (1981). "Daglish, Henry (1866–1920)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ↑ Oliver 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ "Political Unity". Daily Standard. 6 December 1918. p. 6. Retrieved 22 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "Royal Commission Into Parliamentary Deadlocks – Volume 2 Background Papers" (PDF). Parliament of Western Australia. 1985. p. 20. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Henry Daglish". Parliament of Western Australia. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Death Of Mr. H. Daglish". Western Mail. 19 August 1920. p. 16. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Premiers – Constitutional Centre of Western Australia exhibition". Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The New Labour Leader". The West Australian. 12 July 1904. p. 3. Retrieved 7 March 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 3 "Labor Ministers". Sunday Figaro. 14 August 1904. p. 5. Retrieved 7 March 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Intercolonial News". The Daily News. 8 June 1896. p. 6. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 Spillman, Ken (1985). Identity Prized : A History of Subiaco. University of Western Australia Press. ISBN 0-85564-239-4.

- ↑ "Subiaco". The Inquirer And Commercial News. 24 November 1899. p. 13. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Municipal: The Annual Elections". The Daily News. 20 November 1900. p. 2. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 1–2.

- ↑ "Subiaco Municipal Council". The West Australian. 3 May 1901. p. 6. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Subiaco". Western Mail. 15 November 1902. p. 18. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Subiaco". Western Mail. 6 December 1902. p. 10. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Municipal Elections". The West Australian. 11 November 1903. p. 5. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Personal". The West Australian. 13 October 1902. p. 5. Retrieved 7 March 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "News And Notes". The West Australian. 16 January 1903. p. 4. Retrieved 7 March 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 Buttfield 1979, p. 281.

- 1 2 "State Politics". The West Australian. 8 February 1904. p. 3. Retrieved 10 August 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 52.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 289.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 37.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 37, 66.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 37–38.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 39.

- ↑ "The Forthcoming Election". The Albany Advertiser. 11 May 1904. p. 4. Retrieved 12 August 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 76.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 79–80.

- ↑ "The Political Situation". The West Australian. 9 July 1904. p. 7. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Buttfield 1979, p. 81.

- ↑ "Interview With Mr Daglish". Western Mail. 16 July 1904. p. 15. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "The Political Situation". The West Australian. 11 August 1904. p. 5. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 Black, David (2021). The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook (PDF) (25th ed.). pp. 260–261, 330. ISBN 978-1-925580-43-3 – via Parliament of Western Australia.

- ↑ Oliver 2003.

- 1 2 Oliver 2003, p. 18.

- ↑ "Policy Speech Points". Western Mail. 27 August 1904. p. 32. Retrieved 21 April 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Policy Points". The North Coolgardie Herald. 31 August 1904. p. 10. Retrieved 21 April 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Western Australia Parliamentary Debates: Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly: Fifth Parliament–First Session" (PDF). Parliament of Western Australia. 1904. p. 10. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- 1 2 "Western Australia Parliamentary Debates: Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly: Fifth Parliament–Second Session" (PDF). Parliament of Western Australia. 1905. p. 8. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ↑ "Subiaco". The Guardian : Suburban And Municipal Recorder. 19 November 1904. p. 2. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Reid, G. S.; Oliver, M. R. (1982). The premiers of Western Australia, 1890–1982. Nedlands, W.A.: University of Western Australia Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 0855642149.

- ↑ "The Daglish Ministry Reconstructed". The Southern Cross Times. 10 June 1905. p. 3. Retrieved 6 March 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The Discovery Of Daglish". The Sunday Times. 18 June 1905. p. 4. Retrieved 7 March 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "A Labour Crisis". The Register. 28 June 1905. p. 6. Retrieved 7 March 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Political". Bunbury Herald. 23 August 1905. p. 2. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The Political Outlook". The West Australian. 26 August 1905. p. 7. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Labor Caucus". The Southern Cross Times. 30 September 1905. p. 2. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The Labour Party". Western Mail. 7 October 1905. p. 33. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Mr. Daglish". Coolgardie Miner. 10 October 1905. p. 3. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Defeat Of The Government". The West Australian. 5 October 1905. p. 7. Retrieved 22 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Gregory, Jenny; Gothard, Jan (2009). Historical Encyclopedia of Western Australia. University of Western Australia Press. p. 111. ISBN 9781921401152.

- ↑ "Personal". Coolgardie Miner. 8 June 1907. p. 3. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Mayor Bastow and Councillor Vickers". The Guardian : Suburban And Municipal Recorder. 18 May 1907. p. 3. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Personal". The Evening Mail. 13 June 1907. p. 2. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Municipal Elections". The Sunday Times. 1 December 1907. p. 5. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Subiaco Sanitary Site". The West Australian. 3 December 1908. p. 3. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "Past Club Staff – Subiaco FC". Subiaco Football Club. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Subiaco Oval". inHerit. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ↑ "At age 100, do you deserve a facelift?". Western Suburbs Weekly. 11 November 2008. p. 2.

- ↑ McClelland, Peter (22 June 2008). "Icons". Sunday Times Magazine. p. 12.

- ↑ "Football: The Australian Game: Special Meeting of the Association". The West Australian. 12 April 1906. p. 6. Retrieved 2 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Football: The Set Against Subiaco". The Sunday Times. 30 September 1906. p. 3. Retrieved 2 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Personal". Daily Telegraph And North Murchison And Pilbarra Gazette. 29 July 1920. p. 2. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Mrs. Daglish Dies". The Daily News. 29 May 1946. p. 12. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Woman's Realm". The West Australian. 29 May 1946. p. 3. Retrieved 21 February 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Oliver 2003, p. 22.

- ↑ "Photo F. W. Flood". Western Mail. 3 July 1924. p. 29. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Bizzaca, Kristy (February 2014). "City of Subiaco Thematic History and Framework" (PDF). City of Subiaco. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ↑ "House". inHerit. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

Bibliography

- Buttfield, E. S. (1979). The Daglish Ministry 1904-5 : Western Australia's first Labor Government (MA thesis). University of Western Australia.

- Oliver, Bobbie (2003). Unity is strength: A history of the Australian Labor Party and the Trades and Labor Council in Western Australia, 1899–1999. API Network, Australia Research Institute, Curtin University. ISBN 1920845011. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

Further reading

- Daglish, Henry (1904), Papers relating to his time as Premier of Western Australia – via J S Battye Library

External links

- Inaugural speech

Media related to Henry Daglish at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Henry Daglish at Wikimedia Commons