Herbert Barbee (October 8, 1848 – March 22, 1936[1]) was an American sculptor from Luray, Virginia. He was the son of William Randolph Barbee (1818–1868), also a renowned sculptor, with whom he studied in Florence, Italy for some time.[2] He lived for much of his life in his home county, where he had something of a reputation as an eccentric, and where he was not respected by many of the locals due to his propensity for carving nude figures.[3] At one time he also kept a studio in New York,[2] and in 1887 and 1888 he was active in Cincinnati.[4] During his career he also worked in Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and St. Louis.[5] Eventually he opened a studio in Hamburg, Virginia, not far from his birthplace.[6]

In addition to his own work, Barbee completed several pieces which had been left unfinished by his father at the time of his death,[7] and also carved marble pieces after a number of his father's clay models; one of these, The Star of the West, received a gold medal at the Southern Exposition of 1883.[6] He erected a bust of William, looking up at Mary's Rock, at the old family cemetery in Thornton Gap; placed there in 1930, after the elder Barbee's remains had been moved to a cemetery in Luray, this was removed sometime after the construction of Skyline Drive through the area. It was intended that it should be paired with a bust of Herbert's mother, looking down on her husband from the Rock, but that piece was never completed.[2]

Barbee married, on February 20, 1895, Blanche E. Stover of Luray. With her he had four children: Herbert Randolph, Aurelia Loreta, Mary Frances, and William Clifford.[6] Barbee lived at a house called "Calendine", which had been erected in the 1850s to serve as a general store and stage stop along the Sperryville-New Market turnpike; he used the former store area as his studio.[8] He is buried at the Stover Cemetery in Luray.[1] "Calendine" still stands; it is denoted by a historic marker erected by the Page County Historical Society, which purchased the building in 1968[8] and which today operates the house as a museum.[9]

Work

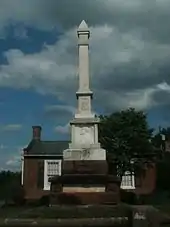

Barbee's most notable work is a memorial to the Confederacy in Luray, erected in 1898; called the "Confederate Heroes Monument", or sometimes "Barbee's Monument", its erection is said to have been inspired by a visit to the battlefield at Gettysburg,[10] although the more immediate reason for its creation was as the focal point of a proposed park, called Henkel Woods Park, whose construction was never completed.[11] Its design is said to have been based on the memory of a sentry Barbee saw standing on the mountain above Thornton Gap one winter's day during the Civil War.[10] The statue is the earlier of two Confederate memorials in Luray, the newer one being erected in 1912. A variety of reasons have been given for the creation of the new statue, including suggestions that the original was disgraceful to the memory of the dead, depicting as it did a soldier in tattered clothing; that the original statue did not face "defiantly north" and so was unacceptable; that the first statue was too far beyond the town's limits to be acceptable; and that Barbee's reputation tainted his work, and so a "purer" representation was needed as a memorial.[3] Even so, one author said of him, "Herbert Barbee made stone speak as life. He left us a marble monument that endures today, an honor to Luray, Page County and Virginia."[12]

Barbee also crafted monuments to the Confederacy in Warrenton and Washington, Virginia.[13][14] The latter was commissioned in 1900, although the date at which it was actually constructed is unknown;[13] the former, a red obelisk which sits on the green just north of the old jail, was unveiled in 1920,[15] and includes as part of its design a bas relief portrait of John Singleton Mosby.[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Herbert Barbee". Find a Grave. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Darwin Lambert (January 1989). The Undying Past of Shenandoah National Park. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-0-911797-57-2.

- 1 2 Ann Denkler (28 February 2010). Sustaining Identity, Recapturing Heritage: Exploring Issues of Public History, Tourism, and Race in a Southern Town. Lexington Books. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-7391-1992-1.

- ↑ Mary Sayre Haverstock; Jeannette Mahoney Vance; Brian L. Meggitt; Jeffrey Weidman (2000). Artists in Ohio, 1787-1900: A Biographical Dictionary. Kent State University Press. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-87338-616-6.

- ↑ Andrea Sutcliffe (1 January 2010). Touring the Shenandoah Valley Backroads. John F. Blair, Publisher. pp. 169–. ISBN 978-0-89587-393-4.

- 1 2 3 4 John Walter Wayland (1969). A History of Shenandoah County, Virginia. Genealogical Publishing Com. pp. 525–. ISBN 978-0-8063-8011-7.

- ↑ Chris Epting (4 June 2009). The Birthplace Book: A Guide to Birth Sites of Famous People, Places, & Things. Stackpole Books. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-8117-4018-0.

- 1 2 "Calendine Historical Marker". Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ "Calendine". Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Confederate Heroes Monument Historical Marker". Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Dan Vaughn (5 May 2008). Luray and Page County Revisited. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-1-4396-3367-0.

- ↑ United Daughters of the Confederacy (1999). The United Daughters of the Confederacy magazine. United Daughters of the Confederacy. p. 19. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- 1 2 "The View from Squirrel Ridge". 11 November 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ "Civil War in Rappahannock County, Virginia". Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (August 1983). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Warrenton Historic District" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.