| Hesperosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

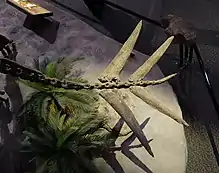

| Mounted skeleton, North American Museum of Ancient Life | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Suborder: | †Stegosauria |

| Family: | †Stegosauridae |

| Genus: | †Hesperosaurus Carpenter, Miles & Cloward, 2001 |

| Species: | †H. mjosi |

| Binomial name | |

| †Hesperosaurus mjosi Carpenter, Miles & Cloward, 2001 | |

Hesperosaurus (meaning "western lizard", from Classical Greek ἕσπερος (hesperos) "western" and σαυρος (sauros) "lizard") is a herbivorous stegosaurian dinosaur from the Kimmeridgian age of the Jurassic period, approximately 156 million years ago.

Fossils of Hesperosaurus have been found in the state of Wyoming and Montana in the United States of America since 1985. The type species Hesperosaurus mjosi was named in 2001. It is from an older part of the Morrison Formation, and so a little older than other Morrison stegosaurs. Several relatively complete skeletons of Hesperosaurus are known. One specimen preserves the first known impression of the horn sheath of a stegosaurian back plate.

Hesperosaurus was a member of the Stegosauridae, quadrupedal plant-eaters protected by vertical bony plates and spikes. It was closely related to Stegosaurus and was similar to it in having two rows of, possibly alternating, plates on its back and four spikes on its tail end. The plates on its back were perhaps not as tall, but were longer. It possibly had a deeper skull than Stegosaurus.

Discovery and species

In 1985, fossil hunter Patrick McSherry, at the ranch of S.B. Smith in Johnson County, Wyoming, found the remains of a stegosaur. As he had difficulty securing the specimen due to the hard rock matrix, he sought help from Ronald G. Mjos and Jeff Parker of Western Paleontological Laboratories, Inc. They, in turn, cooperated with paleontologist Dee Hall of Brigham Young University. At first, it was assumed it represented an exemplar of Stegosaurus. However, Clifford Miles, while preparing the remains, recognised that they belonged to a species new to science.

The type species Hesperosaurus mjosi was named and described in 2001 by Kenneth Carpenter, Clifford Miles, and Karen Cloward. The generic name is derived from the Greek ἕσπερος, hesperos, "western", in reference to its location in the western United States. The specific name honours Mjos who, apart from his involvement in the process of collecting and preparing the holotype, also had a cast of it made, exhibited with the inventory number DMNH 29431 in the Denver Museum of Natural History.[1]

The holotype, HMNH 001 (later HMNS 14), was found in the Windy Hill Member, stratigraphic zone 1 of the lower Morrison Formation,[2] dating from the early Kimmeridgian, about 156 million years old. In 2001, it represented the oldest known American stegosaur. It consists of a nearly complete skull and much of the skeleton. It includes the disarticulated elements of the skull, the rear lower jaws, a hyoid, thirteen neck vertebrae, thirteen back vertebrae, three sacrals, forty-four tail vertebrae, neck ribs, dorsal ribs, chevrons, a left shoulderblade, a complete pelvis, ossified tendons and ten neck and back plates. The skeleton was partly articulated and, in view of healed fractures, belongs to an old individual.[1] It was obtained by the Japanese Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences at Okayama. In 2015, the HMNS permanently closed and the holotype was transferred to the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, where it was renumbered FPDM-V9674[3]

From 1995 onward at the Howe-Stephens Quarry in Big Horn County, Wyoming, named after the historic location of the Howe Ranch, once explored by Barnum Brown, and the new owner Press Stephens, Swiss palaeontologist Hans Jacob Siber excavated stegosaur specimens. The first was SMA 3074-FV01 (also SMA M04), a partial skeleton dubbed "Moritz" after Max und Moritz as an earlier Galeamopus sauropod skeleton from the site had been nicknamed "Max". In 1996/97, specimen SMA 0018 (also mistakenly referred to as SMA V03) was uncovered, dubbed "Victoria" after the feeling of victory the exploring team felt when they discovered Allosaurus "Big Al Two" after the original "Big Al" had been confiscated as federal property. It represents a rather complete skeleton with skull, also preserving skin and horn sheath impressions. A third specimen was found in 2002: SMA L02, dubbed "Lilly" after the sisters Nicola and Rabea Lillich assisting the excavations as volunteers. The specimens are part of the collection of the Aathal Dinosaur Museum in Switzerland. At first they were considered Stegosaurus exemplars. In 2009, initially only "Moritz" and "Lilly" were reclassified as cf. Hesperosaurus mjosi.[4] In 2010, "Victoria" was referred to Hesperosaurus mjosi by Nicolai Christiansen and Emanuel Tschopp.[5]

Carpenter had originally concluded that Hesperosaurus was a rather basal stegosaur. However, Susannah Maidment and colleagues in 2008 published a more extensive phylogenetic study in which it was recovered as a derived form, closely related to Stegosaurus and Wuerhosaurus. They proposed that Hesperosaurus should be considered a species of Stegosaurus, with Hesperosaurus mjosi becoming Stegosaurus mjosi; at the same time Wuerhosaurus was renamed into a Stegosaurus homheni.[6] Carpenter, considering the problem more of a philosophical than a scientific nature, in 2010 rejected the synonymy of Hesperosaurus with Stegosaurus stating that in his opinion Hesperosaurus was sufficiently different from Stegosaurus to be named a separate genus.[7] Christiansen in 2010 judged likewise.[5] In 2017, Raven and Maidment recognized both Miragaia and Hesperosaurus as genera distinct from Stegosaurus.[8]

In 2015, additional specimens were reported: a concentration of at least five individuals discovered at the JRDI 5ES Quarry near Grass Range, Montana, and two individuals found in the Meilyn Quarry at Como Bluff.[9] In 2018, new specimen of H. mjosi was described from Montana.[10]

Description

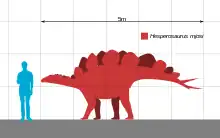

Hesperosaurus was a large stegosaur, reaching 6.5 metres (21 ft) in length and 3.5 metric tons (3.9 short tons) in body mass.[11] Some large individuals may have reached 5 metric tons (5.5 short tons) in body mass.[12]

In 2001 Carpenter provided a diagnosis. Due to his conclusion that Hesperosaurus were rather basal, in it many comparisons were made with the basalmost known stegosaurian Huayangosaurus,[1] that lost their relevance once it became clear that the phylogenetic position was in fact quite derived. In 2008 Maidment indicated three autapomorphies: the possession of eleven back vertebrae; the fourth sacral not being fused to the sacrum; back plates that are longer (from front to rear) than tall. Maidment also provided some traits in which Hesperosaurus was more basal than Stegosaurus armatus. In the atlas, even in adult specimens the neural arches are not fused to the intercentrum. The postzygapophyses, the rear joint processes, of the rear neck vertebrae do not prominently protrude upwards. In the back vertebrae, the neural arches, above the level of the neural canal, are not especially lengthened to above. At the hip region ossified tendons are present. The ribs are expanded at their lower ends. The neural spines of the tail vertebrae are not bifurcated. The lower end of the pubic bone is expanded (spoon-shaped in side view).[6] To Carpenter this differential diagnosis was problematic because he considered Stegosaurus armatus, the type species of Stegosaurus, a nomen dubium and rejected Maidment's lumping of all North-American Stegosaurus material into a single species, the great variability of which making it difficult to establish any differences with Hesperosaurus. He considered Stegosaurus stenops, the name historically given to several well-preserved specimens, a separate species and provided a new differential diagnosis of Hesperosaurus compared to S. stenops. The antorbital fenestra is large instead of very small. The maxilla is short and deep, half as tall as long, instead of having a height a third of the length. The basisphenoid of the lower braincase is short instead of long. Thirteen neck vertebrae are present instead of ten. Thirteen dorsal (back) vertebrae are present instead of seventeen. The middle dorsals have a basal form in possessing a low neural arch rather than a high one. The cervical ribs have expanded lower ends. In the front tail vertebrae, the tops of the neural spines are rounded instead of bifurcated. The front edge of the shoulderblade is indented instead of running parallel to the rear edge. The front blade of the ilium diverges strongly sideways instead of weakly. The rear blade of the ilium has a knob-shaped expansion at the rear end. The front end of the prepubic process has an upward expansion. The plates of the hip and tail base are oval and low instead of high and triangular.[7]

The various published descriptions of Hesperosaurus contradict each other because of changes and differences in interpretation. Originally, Carpenter reconstructed the disarticulated skull elements into a very convex head, modelling it on the shape of Huayangosaurus.[1] The discrepancies in the vertebral count are caused by applying different criteria to the problem whether (and which) cervicodorsal vertebrae should be considered part of the neck or the back. The exact shape of the plates is hard to determine due to erosion. Paul considered the neck plates to be low, but the back plates as taller.[11] Also the Aathal specimens are as yet undescribed. A complete description of the entire material is in preparation by Octávio Mateus.[5]

The number of maxillary teeth were twenty per side, lower than the number with Stegosaurus. Carpenter described them as similar to the teeth of Stegosaurus, though somewhat larger.[1] Peter Malcolm Galton in 2007 established some differences: there are rough vertical ridges present on the upper part of the crown, one per denticle; the fine grooves on the tooth surface are weakly developed.[13]

Osteoderms and skin impressions

Carpenter in 2001 identified ten plates as part of the holotype. He described them as long and low. Asymmetrical bases would indicate that they ran in two rows. The end of the tail bore a "thagomizer" of two pairs of spikes, the front pair being thicker, the rear pair thinner and more horizontally directed to behind.[1]

In 2012, an histological study concluded that these osteoderms, skin ossifications, of Hesperosaurus are essentially identical in structure to those of Stegosaurus. CAT-scans showed that the plates have thin but dense outer walls, filled with thick spongy bone. The bone shows signs of having been remodelled during a metaplastic growth process. Extensive long and wide arterial canals were visible. The spikes have thicker walls and the hollows in the spongy interior are smaller. A single large blood vessel ran along the longitudinal axis of the spike.[14]

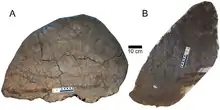

In 2010, a study was published on the soft parts visible with the "Victoria" specimen. It preserves both true impressions of the skin into the surrounding sediment, and natural casts, where the spaces left behind by the rotting of the soft body parts have been filled in with sediment. Additionally on some areas a black layer is present, possibly consisting of organic remains or bacterial mats. A part of the lower trunk flank shows rows of small hexagonal, non-overlapping, convex scales, two to seven millimetres in diameter. Higher on the flank two rosette structures are visible with larger central scales, one being twenty by ten millimetres in size, the other ten by eight millimetres. Apart from the scales, an impression of the lower side of a back plate has been found, covering about two hundred square centimetres. This shows no scales but a smooth surface with low parallel vertical ridges. As it is a true impression, with the life animal grooves would have been present. These grooves would have been about half a millimetre deep and stood about two millimetres apart. The impression probably represented the horn sheath of the plate, as would be confirmed by vertical traces of veins. It is the first direct proof of such sheaths with any stegosaurian. The study considered the presence of a sheath to be a strong indication that the plate had primarily a defensive function, as a horn layer would have strengthened the plate as a whole and provided it with sharp cutting edges. Also the display function would have been reinforced, because the sheath would have increased the visible surface and such horn structures are often brightly coloured. Thermoregulation, on the other hand — another often assumed role of the plates — would have been hampered by an extra insulating layer and the smoothness of the surface, but cannot be entirely ruled out as extant cattle and ducks use horns and beaks to dump excess heat despite the horn covering.[5]

Phylogeny

In 2001 Carpenter performed a cladistic analysis showing that Hesperosaurus was rather basal and related to Dacentrurus:[1]

| Stegosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carpenter was aware that his analysis was limited in scope.[1]

More extensive phylogenetic studies by Maidment recovered Hesperosaurus as a very derived stegosaurid, and the sister species of Wuerhosaurus. The position of Hesperosaurus in the stegosaurid evolutionary tree according to a study from 2009 is shown by this cladogram:[15]

| Stegosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In a 2019 re-evaluation of dacentrurine stegosaurids, Costa and Mateus suggested that, based on their revised diagnosis for the clade Dacentrurinae, Hesperosaurus appears to heave been closely related to Dacentrurus after all, though they refrained from formally reassigning it to that group pending the completion of an expanded phylogenetic analysis.[16]

Paleobiology

In 2015, a study by Evan Thomas Saitta based on the finds in the JRDI 5ES Quarry concluded that Hesperosaurus showed sexual dimorphism. Plates found in the quarry came in two types: a taller one, and a low broad one. Though the back plates of the various individuals were not articulated, Saitta managed to order them into cervical, dorsal and caudal series for each type. This seemed to show that some individuals had tall plates exclusively while others bore broad plates only, which was confirmed by earlier specimens also possessing plates of one kind. Saitta suggested that the tall plates typified the females, while the males were equipped with low plates.[9] The findings of the study were questioned by palaeontologists Kevin Padian and Kenneth Carpenter although no formal scientific studies were published as a rebuttal.[17]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Carpenter, K.; Miles, C.A.; Cloward, K. (2001). "New Primitive Stegosaur from the Morrison Formation, Wyoming". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 55–75. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- ↑ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix". Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329.

- ↑ Sonoda, T.; Noda, Y. (2016). "Transfer of museum collection from the Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences to the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum" (PDF). Memoir of the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum. 15: 93–98.

- ↑ Siber, H.J.; Möckli, U. (2009). The Stegosaurs of the Sauriermuseum Aathal. Aathal: Sauriermuseum Aathal. p. 56.

- 1 2 3 4 Christiansen, N.A.; Tschopp, E. (2010). "Exceptional stegosaur integument impressions from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Wyoming". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 103 (2): 163–171. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0026-0. S2CID 129246092.

- 1 2 Maidment, Susannah C.R.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Upchurch, Paul (2008). "Systematics and phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (4): 367–407. doi:10.1017/S1477201908002459. S2CID 85673680.

- 1 2 Carpenter, K. (2010). "Species concept in North American stegosaurs". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 103 (2): 155–162. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0020-6. S2CID 85068121.

- ↑ Raven, T.J.; Maidment, S.C. (2017). "A new phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria, Ornithischia)" (PDF). Palaeontology. 60 (3): 401–408. doi:10.1111/pala.12291. hdl:10044/1/45349. S2CID 55613546.

- 1 2 Saitta, E.T. (2015). "Evidence for Sexual Dimorphism in the Plated Dinosaur Stegosaurus mjosi (Ornithischia, Stegosauria) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western USA". PLOS ONE. 10 (4). e0123503. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1023503S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123503. PMC 4406738. PMID 25901727.

- ↑ Maidment, Susannah C.R.; Woodruff, D. Cary; Horner, John R. (2018). "A new specimen of the ornithischian dinosaur Hesperosaurus mjosi from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Montana, U.S.A., and implications for growth and size in Morrison stegosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38. e1406366. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1406366. hdl:10141/622747. S2CID 90752660.

- 1 2 Paul, G.S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 224.

- ↑ Farlow, J. O.; Coroian, D.; Currie, P.J.; Foster, J.R.; Mallon, J.C.; Therrien, F. (2022). ""Dragons" on the landscape: Modeling the abundance of large carnivorous dinosaurs of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation (USA) and the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation (Canada)". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25024. PMID 35815600.

- ↑ Galton, P.M. (2007). "Teeth of ornithischian dinosaurs (mostly Ornithopoda) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of the western United States". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 17–47.

- ↑ Hayashi, S.; Carpenter K.; Watabe M.; McWhinney L. (2012). "Ontogenetic histology of Stegosaurus plates and spikes". Palaeontology. 55: 145–161. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01122.x.

- ↑ Mateus, Octávio; Maidment, Susannah C.R.; Christiansen, Nicolai A. (2009). "A new long-necked 'sauropod-mimic' stegosaur and the evolution of the plated dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1663): 1815–1821. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1909. PMC 2674496. PMID 19324778.

- ↑ Costa, Francisco; Mateus, Octávio (13 November 2019). "Dacentrurine stegosaurs (Dinosauria): A new specimen of Miragaia longicollum from the Late Jurassic of Portugal resolves taxonomical validity and shows the occurrence of the clade in North America". PLOS ONE. 14 (11): e0224263. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1424263C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224263. PMC 6853308. PMID 31721771.

- ↑ Chen, Angus (Apr 22, 2015). "Dino 'sexing' study slammed by critics". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aab2534