| Dravidosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

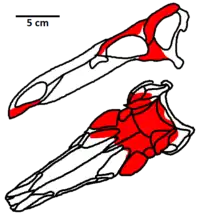

| The holotype skull of Dravidosaurus (GSI SR Pal 1) reconstructed as a stegosaurian skull per its original description, with elements identified in 1979 marked in red | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia (?) |

| Genus: | †Dravidosaurus Yadagiri & Ayyasami, 1979 |

| Species: | †D. blanfordi |

| Binomial name | |

| †Dravidosaurus blanfordi Yadagiri & Ayyasami, 1979 | |

Dravidosaurus is a controversial taxon of Late Cretaceous reptiles, variously interpreted as either a ornithischian, possibly stegosaurian, dinosaur or a plesiosaur. The genus contains a single species, D. blanfordi, known from mostly poorly preserved fossils from the Coniacian (Late Cretaceous) of southern India.

Dravidosaurus was originally described as a late-surviving stegosaur in 1979, younger in age than other known stegosaurs by tens of millions of years. This classification was questioned by Sankar Chatterjee in 1991, who suggested that the fossils were actually plesiosaurian. Chatterjee did however not formally reclassify any of the fossil specimens and did not examine all of them. Since 1991, researchers have variously followed Chatterjee's assessment, maintained Dravidosaurus as a stegosaur, or considered it an indeterminate ornithischian dinosaur.

Researchers in favor of a stegosaurian identity point to the presence of plates and spikes among the fossils, as well as certain morphological features. In 2017, Peter Galton and Krishnan Ayyasami reaffirmed that Dravidosaurus was a stegosaur and announced that further likely stegosaurian fossils from the same original site were currently being studied.

Discovery and naming

Dravidosaurus blanfordi was described in 1979 by P. M. Yadagiri and Krishnan Ayyasami,[1][2] based on fossils recovered from the Coniacian[3][4] Anaipadi Formation of the Trichinopoly Group in southern India during the 1970s.[5] The fossils were discovered at a site west of the village of Siranattam.[1] The Dravidosaurus fossils were the first fossils assigned to a ornithischian dinosaur to be reported from India.[6]

The fossils attributed to Dravidosaurus included the holotype GSI SR Pal 1, a partial skull, as well as fossils identified as an isolated tooth, a sacrum, an ilium, an ischium, an armor plate, and a tail spike, designated (in order) as GSI SR Pal 2–7.[7] Yadigiri and Ayyasami identified several of the skull bones in GSI SR Pal 1, of which the most well-preserved were the parietals, frontals, supraorbitals, squamosal, and quadrate.[1] In addition to the armor plate GSI SR Pal 6, nine other fossils identified as armor plates were found associated with the referred specimens.[1] These fossils have since their discovery been housed in the Palaeontological Laboratory of the Geological Survey of India.[7] The fossils attributed to Dravidosaurus were at the time of its description determined to not be worn and to indicate that there had not been much transportation before burial. The hard limestone matrix around the fossil made extraction and preparation, done using a dental drill and chiselling, difficult.[1]

The generic name Dravidosaurus comes from Dravidanadu, a term often used for the southern part of India in which the Trichinopoly Group is situated.[7] Dravidosaurus thus literally means "Dravidanadu lizard",[8][9] though the name is sometimes interpreted as "lizard from south India".[9] The specific name blanfordi honours William Thomas Blanford, responsible for the pioneering research on the Cretaceous in southern India.[7]

Classification and description

Original description

Yadagiri and Ayyasami identified Dravidosaurus as a stegosaur mainly based on features of the skull (GSI SR Pal 1) and the isolated tooth found associated with it (GSI SR Pal 2). Although differing in some characteristics, they determined that the skull was similar to that of Stegosaurus and that the tooth, merely 3 millimetres (0.1 in) long, closely resembled the teeth referred to other stegosaurian genera such as Kentrosaurus. The presence of fossil elements identified as armor plates and spikes were also interpreted as suggesting a stegosaurian identity. Yadagiri and Ayyasami placed Dravidosaurus in the subfamily Stegosaurinae.[1][lower-alpha 1]

Since they also identified what they considered to be diagnostic traits among the fossils, differentiating them from other stegosaurs known at the time, Yadagiri and Ayyasami erected the new genus Dravidosaurus.[1] In terms of the proportions of the skull itself, Dravidosaurus was determined to be similar to Stegosaurus.[11] Among the features that distinguished GSI SR Pal 1 were the postfrontal being absent, the beak being slightly different from that of Stegosaurus, the postorbital being thin and straight, and the pterygoid being thick and rectangular. GSI SR Pal 2 was distinguishable from the similar teeth of Kentrosaurus through possessing three rather than six crenulations. In addition to these features, Yadagiri and Ayyasami also distinguished Dravidosaurus by features of its sacrum, which indicated that it possessed ribs that were more slender than those of Kentrosaurus.[1]

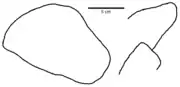

If Dravidosaurus blanfordi was a stegosaur, it would have been one of small size.[7] In fact, at an estimated length of just three metres (10 ft),[9][11] Dravidosaurus would be the smallest known stegosaur.[11] Its narrow skull was reconstructed by Yadagiri and Ayyasami to have measured 20 centimetres (7.9 in) long and 7 centimetres (2.8 in) wide,[1] making it proportionally smaller relative to the rest of the body when compared to stegosaurs known at the time.[11] One part of the skull, identified as the anterior portion of the premaxilla, preserved parts of a stout, curved up, and pointed beak, 3.5 centimetres (1.4 in) long.[1] Among the fossils of Dravidosaurus, Yadagiri and Ayyasami identified ten armor plates and a spike. The plates were largely triangular in shape, with stout bases. They were otherwise relatively thin, about 1 centimetre (0.4 in) in thickness. The referred plates ranged in height from 5 to 25 centimetres (2–9.8 in) and in length from 3 to 15 centimetres (1.2–5.9 in).[1] The spike, identified as a tail spike,[11] measured 15 centimetres (5.9 in) in length and was slightly curved.[1] Assuming a stegosaurian identity, this spike possessed a notable unique trait in that it had an expanded middle region;[11] it bulged at the center with a diameter of 3 centimetres (1.2 in) before tapering towards the base, where it had a diameter of 2.2 centimetres (0.9 in).[1] If Dravidosaurus was a stegosaur, it would like other stegosaurs have been herbivorous.[8]

Classification debate

.png.webp)

Examinations of the poorly preserved[11] fossils referred to Dravidosaurus have since their discovery caused some researchers to either doubt their identity as stegosaurian or consider the taxon a nomen dubium.[5][6][12] Most notably, the American palaeontologist Sankar Chatterjee visited the site in 1991 and expressed doubt that the fossils were dinosaurian at all. Chatterjee instead interpreted the Dravidosaurus fossil material he examined as the "highly weathered" pelvic and hindlimb elements of a plesiosaur, though presented no concrete morphological evidence.[3][13] Chatterjee and Dhiraj Kumar Rudra also described fossil plesiosaur material from the same site as the Dravidosaurus fossils in 1996.[3] Neither publication formally reidentified or reclassified any of the fossils.[4] In 1996, Chaterjee and Dhiraj K. Rudra still formally classified Dravidosaurus as "Stegosauria nomen dubium", though they once again stated that they during their 1991 visit "could not see anything related to the stegosaurian plates and skull claimed by these authors" and maintained that the bones they had seen might be plesiosaurian.[13]

Opinions on Dravidosaurus have varied within the palaeontological community following Chatterjee's reclassification. Dravidosaurus was still considered a stegosaur, without comment, by Carpenter & Currie (1992)[7] and Loyal, Khosla & Sahni (1998).[2] Several more recent works have either supported Chatterjee's opinion that the fossils are plesiosaurian, such as Verma (2015),[14] Verma et al. (2016),[15] and Rozadilla et al. (2021),[16] or maintained that independent redescription and assessment of it is needed, such as Maidment (2010).[3] Wilson, Barrett & Carrano (2011) listed Dravidosaurus as an ornithischian, though did not view this as "demonstrable".[17] Tidwell & Carpenter (2005) considered Dravidosaurus to be a "questionably identified ornithischian dinosaur".[18] Khosla & Lucas (2020) likewise referred to Dravidosaurus as an ornithischian dinosaur, though noted that its taxonomic validity was "under discussion".[19]

Chatterjee's suggestion that Dravidosaurus was a plesiosaur was first explicitly questioned by Peredo Superbiola et al. (2003). This study pointed out that the skull and armor plates figured in the original description, specimens Chatterjee had admittedly not examined, were "certainly not plesiosaurian" but also stated that the fossils were in need of redescription.[4] Similar criticism was offered by Galton & Upchurch (2004), who also noted that the skull and armor plate described in 1979 could not be from a plesiosaur and consequently maintained Dravidosaurus as a stegosaur.[11] Fastovsky & Weishampel (2005) followed Galton & Upchurch's opinion, noting that features of the skull as well as the presence of plates and spikes suggested that Dravidosaurus was a stegosaur.[20] In 2012, Galton again affirmed his belief that Dravidosaurus was a stegosaur due to the presence of plates and a stegosaur-like tooth among the material. Galton also encouraged new examinations of the specimens.[21] The 'Dino Directory' of the London Natural History Museum, written by Paul Barrett, considers Dravidosaurus to be a stegosaurian dinosaur, noting that its fossils were "once thought" to have been plesiosaurian but also that its taxonomical classification is not yet agreed.[8]

In 2017, Galton and Ayyasami together reaffirmed the stegosaurian classification of Dravidosaurus, stating that they saw no similarities between the photographs of the fossils of Dravidosaurus in its original description and the pelvic and hindlimb elements of plesiosaurs. They noted that the small tooth referred to Dravidosaurus was especially unlikely to be plesiosaurian. Furthermore, Ayyasami announced that he was in the process of working on new undescribed and likely stegosaurian bones from the original site of the Dravidosaurus fossils.[22]

Implications

No certain and undisputed stegosaurian fossil remains have been recovered in deposits from the Late Cretaceous. If Dravidosaurus was a stegosaur, it would consequently represent the last known member of the group by a timeframe of tens of millions of years. This would suggest either that the stegosaurian fossil record is poorly sampled throughout the world or that the stegosaurs persisted in what today is India for a long time after they had gone extinct elsewhere.[12]

Palaeoenvironment

The Anaipadi Formation preserves fossils from a neritic environment (the relatively shallow part of the ocean above the drop-off of the continental shelf).[14] The Dravidosaurus fossils come from the upper portion of the unit, which is marked by the presence of the ammonite Kossmaticeras theobaldianum.[1] The Anaipadi Formation preserves a rich mollusc fauna,[14] including common fossils of ammonites and inoceramids,[23] as well as brachiopods. Fossils of marine reptiles have also been found, although they are rare.[14] It has been suggested that the abundant brachiopods and inoceramids in the upper Anaipadi Formation indicates a transgressive environment.[23]

In addition to the marine life found in the upper Anaipadi Formation, terrestrial matter was in the area evidently prone to being carried out to sea. Among other finds recovered in the unit are for instance a large amount of petrified wood.[23] The presence of large quantities of wood indicates that land with dense vegetation was located relatively close to the marine environment in which the Dravidosaurus fossils were buried, meaning that it is not impossible that it (if a terrestrial animal) could have been carried out to sea.[1]

Other than Dravidosaurus, no prospective dinosaur fossils have been reported from the Anaipadi Formation or the Trichinopoly Group as a whole. The overlying Ariyalur Group, which dates to the Campanian and Maastrichtian, has however preserved scant theropod and sauropod fossil material and, according to Yadagiri and Ayyasami in 1979, possibly further stegosaurian fossils.[1] These supposed even later stegosaurian fossils have however never been figured or formally described.[21] In 2017, Galton and Ayyasami reinterpreted some previously assigned Maastrichtian "stegosaur" fossils as sauropod bones but noted that stegosaurs may still have survived to the Maastrichtian in India due to the presence of the ichnogenus Deltapodus, commonly identified as stegosaurian footprints, in the Maastrichtian-age Lameta Formation.[22]

Notes

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Yadagiri, P., and Ayyasami, K., (1979). "A new stegosaurian dinosaur from Upper Cretaceous sediments of south India." Journal of the Geological Society of India, 20(11): 521–530.

- 1 2 Loyal, Raminder S.; Khosla, Ashu; Sahni, Ashok (1998). "Gondwanan dinosaurs of India: Affinities and palaeobiogeography". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 26 (2): 630. doi:10.1016/S0899-5362(97)83516-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Maidment, Susannah C. R. (2010). "Stegosauria: a historical review of the body fossil record and phylogenetic relationships". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 103 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0023-3. ISSN 1661-8734. S2CID 84415016.

- 1 2 3 Pereda Superbiola, Xabier; Galton, Peter M.; Torcida, Fidel; Huerta, Pedro; Izquierdo, Luis Ángel; Montero, Diego; Pérez, Gustavo; Urién, Victor (2003). "First Stegosaurian Dinosaur remains from the Early Cretaceous of Burgos (Spain), with a review of Cretaceous stegosaurs". Estudios Geológicos. 55 (2): 148. doi:10.7203/sjp.18.2.21640.

- 1 2 Parmar, Varun; Prasad, G. V. R. (2020). "Vertebrate evolution on the Indian raft - Biogeographic conundrums". Episodes Journal of International Geoscience. 43 (1): 461–475. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2020/020029.

- 1 2 Prasad, Guntupalli V. R. (2020). "First Ornithischian and Theropod Dinosaur Teeth from the Middle Jurassic Kota Formation of India: Paleobiogeographic Relationships". Biological Consequences of Plate Tectonics. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer. p. 22. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-49753-8_1. ISBN 978-3-030-49752-1. S2CID 229665927.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carpenter, Kenneth; Currie, Philip J. (1992). Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-521-43810-0.

- 1 2 3 "Dravidosaurus". Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 Lambert, David (1983). A Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Diagram Group. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-380-83519-5.

- ↑ Rauhut, O.W.M.; Carballido, J.L.; Pol, D. (2021). "First Osteological Record of a Stegosaur (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Upper Jurassic of South America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (6): e1862133. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1862133. S2CID 234161169.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Peter M. Galton; Paul Upchurch (2004). "Stegosauria". In David B. Weishampel; Peter Dodson; Halszka Osmólska (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 343–362. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- 1 2 Raven, Thomas J. (2021). The Taxonomic, Phylogenetic, Biogeographic and Macroevolutionary History of the Armoured Dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Brighton.

- 1 2 Chatterjee, S., and Rudra, D. K. (1996). "KT events in India: impact, rifting, volcanism and dinosaur extinction," in Novas & Molnar, eds., Proceedings of the Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium, Brisbane, Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 39(3): iv + 489–731 : 489-532

- 1 2 3 4 Verma, Omkar (2015). "Cretaceous vertebrate fauna of the Cauvery Basin, southern India: Palaeodiversity and palaeobiogeographic implications". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 431: 53–67. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.04.021. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ↑ Verma, Omkar; Khosla, Ashu; Goin, Francisco J.; Kaur, Jasdeep (2016). "Historical biogeography of the Late Cretaceous vertebrates of India: Comparisons of geophysical and paleontological data". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 71: 320.

- ↑ Rozadilla, Sebastián; Agnolín, Federico; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (2021). "Ornithischian remains from the Chorrillo Formation (Upper Cretaceous), southern Patagonia, Argentina, and their implications on ornithischian paleobiogeography in the Southern Hemisphere". Cretaceous Research. 125: 104881. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104881. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ↑ Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Barrett, Paul M.; Carrano, Matthew T. (2011). "An associated partial skeleton of Jainosaurus cf. septentrionalis (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Chhota Simla, Central India". Palaeontology. 54 (5): 981–998. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01087.x. hdl:2027.42/86940. S2CID 55975792.

- ↑ Tidwell, Virginia; Carpenter, Kenneth (2005). Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.

- ↑ Khosla, Ashu; Lucas, Spencer G. (2020), Khosla, Ashu; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.), "Historical Background of Late Cretaceous Dinosaur Studies and Associated Biota in India", Late Cretaceous Dinosaur Eggs and Eggshells of Peninsular India: Oospecies Diversity and Taphonomical, Palaeoenvironmental, Biostratigraphical and Palaeobiogeographical Inferences, Topics in Geobiology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, vol. 51, pp. 31–56, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56454-4_2, ISBN 978-3-030-56454-4, S2CID 226750092

- ↑ Fastovsky, David E.; Weishampel, David B. (2005). The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-0-521-81172-9.

- 1 2 Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; Díaz-Martínez, Ignacio; Salgado, Leonardo; Valais, Silvina de (2015-12-27). "SÍNTESIS DEL REGISTRO FÓSIL DE DINOSAURIOS TIREÓFOROS EN GONDWANA". Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina (in Spanish). 15 (1): 90–107. doi:10.5710/PEAPA.21.07.2015.101. hdl:11336/57610. ISSN 2469-0228.

- 1 2 Peter M. Galton; Krishnan Ayyasami (2017). "Purported latest bone of a plated dinosaur (Ornithischia: Stegosauria), a "dermal plate" from the Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) of southern India". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 285 (1): 91–96. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2017/0671.

- 1 2 3 Ayyasami, Krishnan (2006). "Role of oysters in biostratigraphy: A case study from the Cretaceous of the Ariyalur area, southern India". Geosciences Journal. 10 (3): 237–247. doi:10.1007/BF02910367. ISSN 1598-7477. S2CID 140680046.