Sasanian Hind | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 262–484 CE | |||||||||||||||

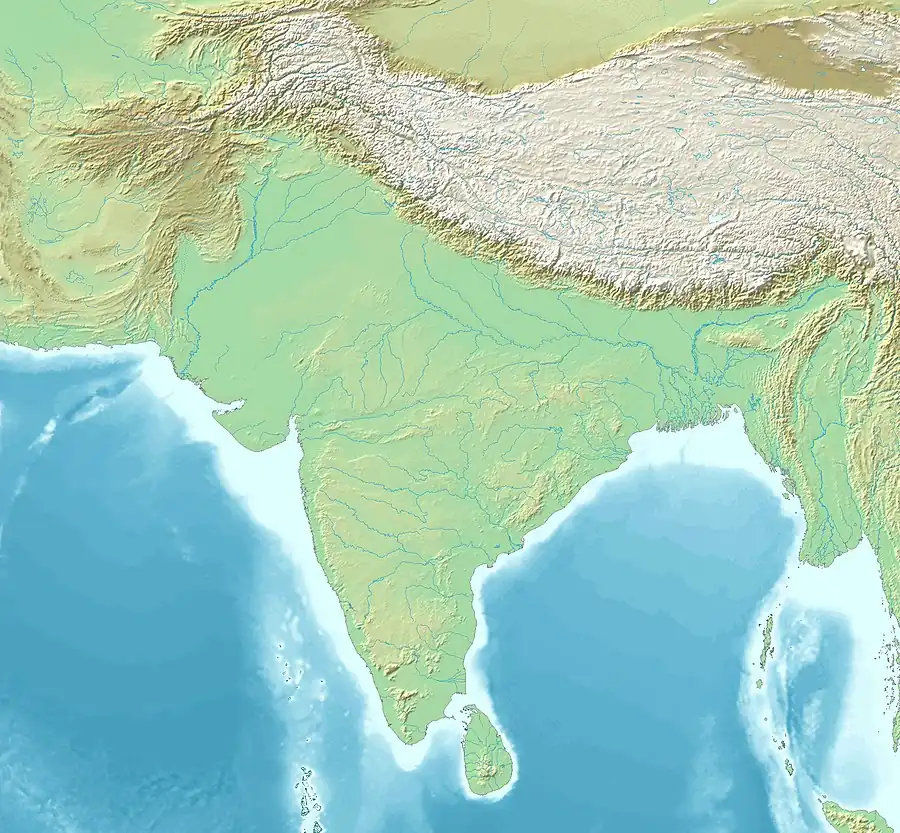

Approximate location of Sasanian Hind and neighbouring polities in South Asia, circa 350 CE.[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 262 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 484 CE | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India Pakistan | ||||||||||||||

Hind (also spelled Hindestan) was the name of a southeastern Sasanian province lying near the Indus River. The boundaries of the province are obscure. The Austrian historian and numismatist Nikolaus Schindel has suggested that the province may have corresponded to the Sindh region, where the Sasanians notably minted unique gold coins of themselves.[2] According to the modern historian C. J. Brunner, the province possibly included—whenever jurisdiction was established—the areas of the Indus River, including the southern part of Punjab.[3]

Territorial claims

The Sasanians toppled the Parthian Empire in 224 CE, and eastern Parthian territories were probably captured under Ardashir I (224-240 CE) and his son Shapur I (240-272 CE).[4] Sakastan was seized around 233 CE by Ardashir in his Great Eastern Campaign, who then captures Herat, Nishapur and Merv.[4] These territories became the basis for further expansion into Central Asia and India.[4]

Sasanian rulers claimed control of vast areas of northwestern India in their inscriptions, starting with the reign of Shapur I and his inscription at Ka'ba-ye Zartosht:[4]

[I] am ruler of [...] Hind [India], and the Kushanshahr up to Peshawar/Pashkibur"

— Shapur I's inscription at the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht (c. 262 CE)

Shapur I installed his son Narseh as "King of the Sakas" in the areas of Eastern Iran as far as Sindh.[5] Narseh is named "King of Sind" in the Naqsh-e Rostam inscription as well as in the Paikuli testament of his father Shapur I:[6]

"husrav-nersah nām ēr mazdesn nersah šāh hind sagestān ud tūrestān dā (ō) drayā"

"Our son the Aryan, the Mazdayasnian Narsē, king of India, Sakestān and Turān to the seashore."

Two inscriptions during the reign of Shapur II (ruled 309–379 CE) mention his control of the regions of Sindh, Sakastan and Turan.[8] Still, the exact term used by the Sasanian rulers in their inscription is Hndy, similar to Hindustan, which cannot be said for sure to mean "Sindh".[9]

Al-Tabari mentioned that Shapur II built many cities in Sind and Sakastan.[10][11] Several governors of the Sasanian Province of Sakastan are known, such as Shapur Sakanshah during the reign of Shapur II (r. 309–379), and as late as Aparviz in the 7th century.

Expansion into Gandhara and Punjab (c. 350–358 CE)

Around 350 CE, Shapur II gained the upper hand in his conflict against the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom and took control of large territories in areas now known as Afghanistan and Pakistan, possibly as a consequence of the destruction of the Kushano-Sasanians by the Chionites.[12] The Kushano-Sasanians still ruled in the north.

Important finds of Sasanian coinage beyond the Indus river in the city of Taxila only start with the reigns of Shapur II (r. 309-379) and Shapur III (r. 383-388), suggesting that the expansion of Sasanian control beyond the Indus was the result of the wars of Shapur II "with the Chionites and Kushans" from 350 to 358 CE as described by Ammianus Marcellinus.[13]

The Sasanians are known to have minted coinage south of the Hindu-Kush, particularly in the area of Kabulistan.[14] Local Sasanian coins were minted in this area during the last part of the reign of Shapur II, around 364-379 CE, with the probable intent of paying for local Sasanian troops fighting against the Kidarites.[14] The Sasanians probably maintained control until Bactria fell to the Kidarites under their ruler Kidara around 360 CE,[15] and Kabulistan fell to the Alchon Huns circa 385 CE.[13][14]

Sasanian-type coinage of Sindh (325-480 CE)

According to R.C. Senior, "the Province of Sind, the floodplain of the Indus river from its mouth to the city of Multan, was the furthest extent of Sassanian dominion in the south-east."[18] A series of Sasanian-style issues is known, minted from 325 to 480 CE in Sindh, from Multan to the mouth of the Indus river in the southern part of modern Pakistan, with the coin type of successive Sasanian Empire rulers, from Shapur II to Peroz I.[9][5] Together with the coinage of the Kushano-Sasanians, these coins are often described as "Indo-Sasanian", and are part of Indo-Sasanian coinage.[19] They form an important part of Sasanian coinage.

Besides Sindh, these coins have also been recovered from the areas of Baluchistan and Kutch.[9] The coins are made of gold only, have a weight of around 7.20 grams, making them similar to the traditional "heavy" Sasanian dinars.[9] The number of coins so far discovered suggests a significant volume of coinage, equivalent to about half of the more famous Kushano-Sassanian coinage.[9] However, the time span of 150 years covered by the Sindh coins is much longer than the roughly 50 years time span of the Kushano-Sasanians, suggested about 1/6th of the Kushano-Sasanian output per time unit.[9]

The coins are not the usual Sasanian imperial type, and the legend around the portrait tends to be degraded Middle Persian in the Pahlavi script, but they have the Brahmi script character Śrī (![]() "Lord") in front of the portrait of the King.[9][20] The coins suggest some sort of Sasanian control of Sind during the 5th century, a recognition of Sasanian overlordship,[9] but the precise extent of the Sasanian presence or influence is unknown.[21][20] The facts that these coins do not use the traditional Sasanian imperial titulature, that they do not use the Sasanian weight standards, and that the standard Sasanian silver monetary standard was not in circulation in the region, all suggest that the Sasanians were actually not ruling directly in Sindh.[9] Still, such vast influence from the Arabic peninsula to the Sindh and the Kushan realm probably provided the Sasanians with a remarkable position in terms of maritime trade, giving them a sort of trade monopoly.[22]

"Lord") in front of the portrait of the King.[9][20] The coins suggest some sort of Sasanian control of Sind during the 5th century, a recognition of Sasanian overlordship,[9] but the precise extent of the Sasanian presence or influence is unknown.[21][20] The facts that these coins do not use the traditional Sasanian imperial titulature, that they do not use the Sasanian weight standards, and that the standard Sasanian silver monetary standard was not in circulation in the region, all suggest that the Sasanians were actually not ruling directly in Sindh.[9] Still, such vast influence from the Arabic peninsula to the Sindh and the Kushan realm probably provided the Sasanians with a remarkable position in terms of maritime trade, giving them a sort of trade monopoly.[22]

The expansion of the Sasanians in northwestern India, which put an end to the remnants of Kushan rule, may also have been done at the expense of the Western Satraps and the Satavahanas.[23]

Sindh coinage of Sasanian Empire rulers from Shapur II down to Peroz I are known, covering approximately the period from 325 to 480 CE.[5] The last coins of the series, those copied on Peroz I (r. 459–484), deviate from the series as they introduce a Brahmi legend, often with the title "Rana Datasatya".[9] Paradoxically, several of the Sasanians kings have more dinar gold coins known from the Sindh mints than from the regular Sasanian mints: this is the case of Shapur III and Bahram V, both of whom only have about five regular Sasanian dinar gold coins known, compared to nine and thirteen respectively for the Sindh mints as of 2016.[9] To explain this, R.C. Senior has suggested that Shapur III, who had a very troubled reign and suffered defeats at the hand of the Kushans, had been unable to issue gold coinage and had to take refuge in Sindh where he was able to strike his beautiful coins, some with the Sri symbol, and some without.[17]

Sasanians at Ajanta

The Buddhist caves of Ajanta have several frescos with characters with foreigners' faces or dresses, dating to circa 480 CE. While scholars generally agree that these murals confirm trade and cultural connections between India and Sassanian west, their specific significance and interpretation varies.[24][26]

Such murals suggest a prosperous and multicultural society in 5th-century India active in international trade.[24] These also suggest that this trade was economically important enough to the Deccan region that the artists chose to include it with precision.[24]

Additional evidence of international trade includes the use of the blue lapis lazuli pigment to depict foreigners in the Ajanta paintings, which must have been imported from Afghanistan or Iran. It also suggests, states Branacaccio, that the Buddhist monastic world was closely connected with trading guilds and the court culture in this period.[24] A small number of scenes show foreigners drinking wine in Caves 1 and 2. In Cave 1, there are also four "foreign" bacchanalian groups (one now missing) at the middle of each quadrant of the elaborate ceiling painting.[26]

Defeat against the Hephthalites (484 CE)

In 484 CE, the Sasanian Emperor Peroz I was defeated by the Hephthalites, and had to ceede the area to Bactria to them.[27] Around the same time, the Sasanian Empire probably also had to ceede the territory of Zabulistan to the Nezak Huns.[27]

Later coinage of Sindh

Later issues of the Peroz design abandon the degraded Palhavi legend altogether as well as the Sri mark, and instead used a Brahmi legend Rana Datasatya.[9][29][30][28] These later imitations of Sasanian coins after 480 CE may have been made by the Hephthalites/ Alchon Huns, who added a Hunnic tamgha to the design, after they took over the northwestern Indian provinces.[5] The quality of the coins also becomes very much degraded by that time, and the actual gold content becomes quite low.[9]

References

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 21, 25. ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ Schindel 2016, p. 127.

- ↑ Brunner 2004, pp. 326–336.

- 1 2 3 4 Alram, Michael (1 February 2021). The Numismatic legacy of the Sasanians in the East (Sasanian Iran in the Context of Late Antiquity: The Bahari Lecture Series at the University of Oxford). BRILL. p. 5. ISBN 978-90-04-46066-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Senior, R.C. (1991). "The Coinage of Sind from 250 AD up to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter. 129 (June–July 1991): 3–4.

- 1 2 Sauer, Eberhard (5 June 2017). Sasanian Persia: Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. Edinburgh University Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-4744-2068-6.

- ↑ "The trilingual inscription of Šābuhr at “Kaaba i Zardušt” (ŠKZ)" (transcription of full text with English translation)

- ↑ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 17. ISBN 9780857716668.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Schindel, Nikolaus; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj; Pendleton, Elizabeth (2016). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: adaptation and expansion. Oxbow Books. pp. 126–129. ISBN 9781785702105.

- ↑ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 18. ISBN 9780857716668.

- ↑ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9781474400305.

- ↑ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9781474400305.

- 1 2 Ghosh 1965, pp. 790–791.

- 1 2 3 Alram, Michael (1 February 2021). The Numismatic legacy of the Sasanians in the East (Sasanian Iran in the Context of Late Antiquity: The Bahari Lecture Series at the University of Oxford). BRILL. p. 5. ISBN 978-90-04-46066-9.

- ↑ The Huns, Hyun Jin Kim, Routledge, 2015 p.50 sq

- ↑ Senior, R.C. (1991). "The Coinage of Sind from 250 AD up to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society. 129 (June–July 1991): 3–4.

- 1 2 Senior, R.C. (2012). "Some unpublished ancient coins" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter. 170 (Winter): 17.

- ↑ Senior, R.C. (2012). "The Coinage of Sind from 250 AD up to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter. 129 (Winter): 17.

- ↑ Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2019). Negotiating Cultural Identity: Landscapes in Early Medieval South Asian History. Taylor & Francis. pp. 177–178. ISBN 9781000227932.

- 1 2 ALRAM, MICHAEL (2014). "From the Sasanians to the Huns New Numismatic Evidence from the Hindu Kush". The Numismatic Chronicle. 174: 267. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 44710198.

- ↑ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 137. ISBN 9780857716668.

- ↑ Banaji, Jairus (2016). Exploring the Economy of Late Antiquity: Selected Essays. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9781107101944.

- ↑ Mahajan, Vidya Dhar (2016). Ancient India. S. Chand Publishing. p. 335. ISBN 9789352531325.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brancaccio, Pia (2010). The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion. BRILL. pp. 80–82, 305–307 with footnotes. ISBN 978-9004185258.

- ↑ DK Eyewitness Travel Guide India. Dorling Kindersley Limited. 2017. p. 126. ISBN 9780241326244.

- 1 2 Spink 2007, p. 27.

- 1 2 Alram, Michael (1 February 2021). The Numismatic legacy of the Sasanians in the East (Sasanian Iran in the Context of Late Antiquity: The Bahari Lecture Series at the University of Oxford). BRILL. p. 9. ISBN 978-90-04-46066-9.

- 1 2 Senior, R.C. (1991). "The Coinage of Sind from 250 AD up to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society (129): 4.

- ↑ Senior, R.C. (1991). "The Coinage of Sind from 250 AD up to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter. 129: 3–4.

- ↑ Senior, R.C. (1996). "Some new coins from Sind" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter. 149: 6.

Sources

- Brunner, C. J. (2004). "Iran v. Peoples of Iran (2) Pre-Islamic". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, Vol. XIII, Fasc. 3. New York. pp. 326–336.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schindel, Nikolaus (2016). "The Coinages of Paradan and Sind in the Context of Kushan and Kushano-Sasanian Numismatics". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785702082.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8. (registration required)

- Ghosh, Amalananda (1965). Taxila. CUP Archive. pp. 790–791.

- Spink, Walter M. (2007). Ajanta: History and Development, Volume 5: Cave by Cave. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15644-9.

.svg.png.webp)

._AD_293-303._AR_Drachm_(26mm%252C_3.80_g%252C_3h)._Style_J%252C_Phase_3._Sakastan_mint.jpg.webp)

_Struck_circa_320-379_CE.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)