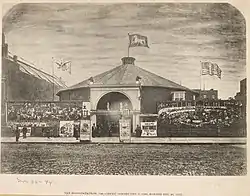

| Hippotheatron | |

|---|---|

The Hippotheatron in New York (1872) | |

| General information | |

| Location | Manhattan, New York City |

| Opened | 1864 |

| Demolished | 1872 |

The Hippotheatron was an entertainment venue in New York built for large-scale circus and equestrian performances although ballets, dramas and pantomimes were also held there. Opened in 1864, it was destroyed by fire in 1872 which resulted in the death of most of the animals in the menagerie.[1]

Design

_-_Circus_images%252C_Hippotheatron.jpg.webp)

It was built for Dick Platt in 1864 as the New York Circus on the same lot at 86/94 E. 14th Street in Manhattan previously occupied by James M. Nixon's Alhambra Circus in New York.[2] The theatre historIan T. Allston Brown (1836–1918) in his A History of the New York Stage (1903) wrote at length about the building and its history, stating that it was constructed of corrugated and ridged iron, was fireproof, and was built after the model of the Champs-Élysées in Paris.[3] The main building was 110 feet in diameter while the dome rose to the height of 75 feet, surmounted by a cupola. The iron roof was affixed to heavy timber posts. The main supports of the dome were a series of columns surmounted by richly ornamented caps. These columns were also cased with corrugated iron. There were three distinct areas for the audience: the orchestra seats, dress circle, and the pit, with a wide promenade in the rear, around the entire circle of seats. The 600 orchestra seats were composed of arm sofas, for which 75 cents was charged. In the rear was the dress circle, in which there was seating capacity for 500 persons. The pit could accommodate, comfortably seated, 600 people. In addition to this, there was standing room in the promenade and other parts of the house capable of accommodating 600 men, making standing room for 1,400 persons, and, when crowded, 2,000 could be packed away.[4]

The ring was the largest (with the exception of a travelling show) ever used in the United States, being 43 feet 6 inches, which is 1 foot 6 inches larger than Astley's Amphitheatre in London, and 6 inches bigger than the Cirque Napoléon at Paris. There were two ring entrances exactly opposite one another; this item alone was a great improvement, both for spectacular pieces and for battoute leaping. There were two entrances to the building, the chief one being a beautiful portico in the shape of an Italian arch 23 feet high and 22 feet in width; within was an interior vestibule 12 feet in depth, with wreathed columns and four niches, in which statues were placed. Over this entrance was the band, which was the dividing line between the 25 cent seats and those costing 50 cents. The structure was among the first in New York to be heated by steam.[4]

New York Circus (1864–1866)

It opened on 8 February 1864[2] with the equestrian company of Marie Macarte among those who appeared on the first night. Music for the performances, everything from equestrian display to ballet and incidental music for dramas and pantomimes, was provided by H. Wayrauch, the resident composer and musical director.[3] The venue immediately became popular with audiences.[5] Spalding & Rogers' Circus, which had just returned from a two years' tour in the seaports of Brazil, Buenos Ayres, Montevideo, and the West Indies, were in residence for four weeks from April 25 to May 21 1864,[6] during which period a new roof was built. In the same year the renowned tightrope dancer Marietta Zanfretta also performed here. Theatrical productions included the pantomimes Harlequin Bluebeard, or, the Good Fairy Preciosa and the Bad Demon Rusifusti (December 1864-February 1865) and Mother Goose! and the Fairy Legend of the Golden Egg (February 1865) as well as the drama Fairy Prince O'Donoughue, or, the White Horse of Killarney (April to May 1865).[1] From 3 October 1864 to 10 June 1865 the manager was James M. Nixon.[1][2]

L. B. Lent's New York Circus (1866–1869)

It was reopened for the winter season on 25 September 1865 with Lewis B. Lent (1813-1887) as the new manager, and the owner Dick Platt sold it to Lent in October 1865. He changed its name to 'Lent's New York Circus' on 6 November[2] and continued the season until 27 May 1866; it was reopened by Lent on 24 September 1866. It had been announced to open on 11 September, but the epizootic prevailed to such an extent among the horses that he was compelled to defer it. During the summer recess many improvements were made in the building. The earth was excavated, the ring and surrounding seats lowered, and a hanging gallery added, thereby materially increasing the seating capacity of the auditorium. Underneath the raised seats the dens of animals and museum curiosities were placed.[2] The front entrance was materially improved by alterations, and a large false front, entirely concealing the iron building from view, was erected and covered with large oil paintings, characteristic of the entertainments within, and the season ended on 4 May 1867.[4] On 15 September 1866 the champion billiards player Cyrille Dion participated in the Tournament of State and Provincial Champions in a round robin tournament at American four ball billiards, with races to 500 points.[7]

The Hippotheatron (1869–1872)

On 17 April 1869 the building was reopened as The Hippotheatron with a show by the circus troupe of Richard Risley Carlisle, who appeared as 'Professor' Risley. Lent remained as manager until 1872.[2] The name 'Hippotheatron' was taken from the Greek 'Hippo' (ἵππος - horse) and 'theatron' (θέατρον - a theatre/viewing place for spectators).[4]

In the summer of 1872 the Hippotheatron was sold to P. T. Barnum,[2] who opened it on 18 November 1872 with the pantomime Bluebeard.[2]

Destruction

The Hippotheatron was destroyed by fire on 24 December 1872. The blaze was first discovered at four o'clock in the morning having been caused by an escape of gas. Despite the gas main being turned off jets of flame were still seen shooting out from among the ruined structure. Fire engines were quickly on the scene.[8] The walls of the building, which were of thin corrugated iron, became quickly heated by the fierce flames at their base, and helped not only to spread flames, but engendered so great a heat that the firemen could not enter the building.[4]

During the winter months the Barnum circus came off the road and the animals were housed at the Hippotheatron.[9] When the fire broke out the animals in their cages began to show signs of fear, and their excitement increased with the noise and heat of the fire. Charles Wells, a keeper among those who slept on the premises near the animal cages, said that he and two others went to the giraffes' cage to break them out but the fire had reached the cage and the men only succeeded in getting a giraffe partly out when it was caught by the flames and sank to the ground.[8] Other animals dashed with terrific force against the sides of their cages, vainly endeavoring to regain their liberty. There were three elephants in the building, confined by chains fastened to the floor. As the fire grew hotter the bears, lions, and leopards were seen with their paws endeavoring to wrench the iron bars of their cages asunder, and, as the flames or heat prevented their keepers from rescuing them, they were abandoned to their fate. None of the keepers had the keys of any of the cages, otherwise some of the animals could have been saved. All the performers lost their wardrobes, and all the dresses which had been made for Bluebeard were likewise consumed. A number of valuable trained dogs belonging to Charles White were also burned.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 Hippotheatron - Broadway World website

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 New York Circuses - Circopedia database

- 1 2 John Franceschina, Incidental and Dance Music in the American Theatre from 1786 to 1923, Volume 3, BearManor Media (2018) - Google Books

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 T. Allston Brown, A History of the New York Stage, Vol. 2, New York: Benjamin Bloom, Inc., 1903, pp. 353-356

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ 'The Hippotheatron' - The New York Times, 24 November 1864, Page 5 (subscription required)

- ↑ William L. Slout, Clowns and Cannons: The American Circus During the Civil War, Emeritus Enterprise Book (2000) - Google Books p. 159

- ↑ Phelan, Michael (1870). The American billiard record: A compendium of important matches since 1854. New York: Phelan & Collender. pp. 38, 41–42, 51, 59, 71. OCLC 16904588. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- 1 2 'Barnum's Last Disaster' - The Sun, New York, December 26, 1872, p. 1

- ↑ Stuart Thayer and William L. Slout, Grand Entree: The Birth of the Greatest Show on Earth, 1870-1875, Emeritus Enterprise Book (1998) - Google Books p. 47