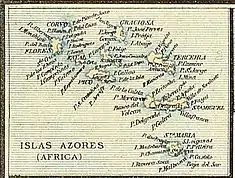

The following article describes the history of the Azores, an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atlantic Ocean, about 1,400 km (870 mi) west of Lisbon, about 1,500 km (930 mi) northwest of Morocco, and about 1,930 km (1,200 mi) southeast of Newfoundland, Canada.

Myth and legend

Stories of islands in the Atlantic Ocean, legendary and otherwise, had been reported since classical antiquity.[1] Utopian tales of the Fortunate Isles (or Isles of the Blest) were sung by poets like Homer and Horace. Plato articulated the legend of Atlantis. Ancient writers like Plutarch, Strabo and, more explicitly, Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy, testified to the real existence of the Canary Islands.

The Middle Ages saw the emergence of a new set of legends about islands deep in the Atlantic Ocean. These were sourced in various places, e.g. the Irish immrama, or missionary sailing voyages (such as the tales of Ui Corra and Saint Brendan[2]) and the sagas of Norse adventurers (such as the Grœnlendinga saga and the saga of Erik the Red). The peoples of the Iberian peninsula, who were closest to the real Atlantic islands, and whose seafarers and fisherman may have seen and even visited them,[3] articulated their own tales. Medieval Andalusian Arabs related stories of Atlantic island encounters in the legend of the 9th-century navigator Khashkhash of Cordoba (told by al-Masudi)[4] and the 12th-century story of the eight Maghurin (Wanderers) of Lisbon (told by Muhammad al-Idrisi).[5]

From these Greek, Irish, Norse, Arab and Iberian seafaring tales – often cross-fertilizing each other – emerged a myriad of mythical islands in the Atlantic Ocean – Atlantis, the Fortunate Islands, Saint Brendan's Island, Brasil Island, Antillia (or Sete Cidades, the island of the Seven Cities), Satanazes, the Ilhas Azuis (Blue Islands), the Terra dos Bacalhaus (Land of Codfish), and so on, which however uncertain, became so ubiquitous that they were considered fact.

According to Bartolomé de las Casas, two dead bodies that looked like those of Amerindians were found on Flores. He said he found that fact in Christopher Columbus' notes, and it was one reason why Columbus presumed that India was on the other side of the ocean.[6]

In A History of the Azores (1813), by Thomas Ashe, the author talks of the discovery of the islands by Joshua Vander Berg of Bruges,[7] who landed there during a storm on his way to Lisbon. This claim is generally discredited among academics today. As were local stories of a mysterious equestrian statue and coins with Carthaginian writing that were purportedly discovered on island of Corvo, or the strange inscriptions found along the coast of Quatro Ribeiras (on Terceira): all unsubstantiated stories that supported the claims of human visitation to the islands before the official record.

But there was some basis in fact, since the Medici maps of 1351 contained seven islands off the Portuguese coast which were arranged in groups of three; there were the southern group, or the Goat Islands (Cabreras), the middle group, or the Wind or Dove Islands (De Ventura Sive de Columbis), and the western islands, or the Brazil Island (De Brazil). The Catalan Atlas (1375) also identifies three islands with the names of Corvo, Flores, and São Jorge, and it was thought that maybe the Genovese had discovered the Azores, and given them those names. But, generally, these stories highlighted that sightings were being made at the end of the 14th century, or at least, the peoples of Europe had a passing knowledge of islands in the Atlantic. Owing to the disorganized politics of the continent there were few nations able to organize an exploration of the Western Sea.

Hypogea

There have been recent discoveries (2010–2011) of hypogea (structures carved into embankments, that may have been used for burials) on the islands of Corvo, Santa Maria and Terceira, that might allude to a human presence on the islands before the Portuguese.[8][9][10] Until recently there was no clear evidence that there were, in fact, other inhabitants on the islands, and archaeological investigations are only now commencing as to the age and relevance of these structures.[10]

Megalithic Structures

New findings were registered at Grota do Medo site, in 2015, regarding large stones that have been used to construct structures or monuments similar to ancient megalithic constructions in Europe. In the same year, a radiocarbon dating was made at Grota do Medo, in a stone carved basin that also had a petroglyph. The authors dated organic matter that deposited in the basin through time. The obtained results by Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Method, was 910 ± 30 years before the present (BP) and the Conventional Radiocarbon Age was 950 ± 30 years BP.

Vikings

Although it was traditionally believed that Portuguese explorers were the first humans to arrive on the Azores, there is evidence to suggest otherwise. In particular, researchers have discovered that 5-beta-stigmasterol is present in sediment samples from between 700 and 850 CE. This compound is found in the feces of livestock such as sheep and cattle, neither of which are native to the islands. The researchers also found evidence of fires from this period being used to clear land for livestock. They also discovered non-native ryegrass in the Azores.[11] On the other hand, mice on the Azores were discovered to have mitochondrial DNA suggesting they first arrived from Northern Europe, suggesting that they were brought to the islands by Norwegian Vikings.[12]

However, geographer Simon Connor comments that a Viking settlement is not certain: “Thanks to widespread trade routes, a mouse from Scandinavia could easily have boarded a ship in what today is Portugal and sailed over to the Azores.”[13]

Exploration

Early appearance on charts

.jpg.webp)

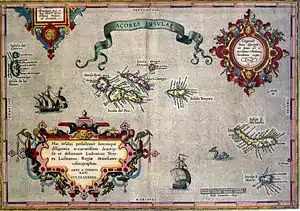

The Azores archipelago began to appear on portolan charts during the 14th century, well before its official discovery date. The first map to depict the Azores was the Medici Atlas (1351). Its depiction was subsequently replicated in the Pizzigani brothers' map of 1367, the Catalan Atlas (1375), the Pinelli–Walckenaer Atlas (1384), the Corbitis Atlas (c. 1385–1410), the charts of Guillem Soler (1380, 1385), Mecia de Viladestes (1413) and others.[14] They are also listed in the Libro del Conoscimiento (c. 1380).[15]

In these maps, the Azores are usually depicted vertically aligned, on a north–south axis, nine islands in three clusters. The island names, in order (from south to north) are usually (with their tentative translation):

bottom cluster:

- lovo or lobo ("island of wolves" (seals?), Santa Maria)

- caprara or cabrera ("island of goats", São Miguel),

middle cluster:

- y de brazil ("island of embers/fire", Terceira)

- li columbi ("island of pigeons", Pico)

- y de la ventura ("island of venture/winds", Faial)

- san zorzo ("island of St. George", São Jorge)

top cluster:

It is notable that two of the names – San Zorzo and Corvis Marinis – would be transferred to the modern Azorean islands. Only Graciosa seems to be routinely missing on these maps. The Madeira archipelago also appears on most of these same maps, with their modern names: legname (Ligurian for "wood", Madeira), porto sancto (Porto Santo), desertas (Desertas) and salvazes (Savage Island).

The source of this information is a mystery. It could simply be derived from pure legend, possibly of Andalusian Arab origin e.g. al-Idrisi speaks of an Atlantic island of wild goats (the Caprera?) and another of "cormorants", a scavenger bird (the "sea crows" of Corvis Marinis?)[16] But outside their erroneous axial tilt, the Azores do seem clustered with reasonable accuracy. From this cartographic record, there seems little doubt that both Madeira and the Azores were discovered, or at least sighted, during the 14th century, well before their official discovery dates.[17]

One hypothesis is that the Azores were discovered in the course of a mapping expedition in 1341 to the Canary Islands, sponsored by King Afonso IV of Portugal, and commanded by the Florentine Angiolino del Tegghia de Corbizzi and the Genoese Nicoloso da Recco.[18] Although not quite described in the 1341 report, Madeira and the Azores might nonetheless have been seen from a distance on the expedition's return via a long sailing arc (volta do mar) from the Canary islands.[19]

Even if they were not discovered by the mapping expedition of 1341 itself, the islands may have been found by any of the numerous Majorcan expeditions that were launched into the Atlantic Ocean in the aftermath, destined for slaving runs on the newly mapped Canary islands.[20] Regardless of whether they were sighted during the 14th century, there seems to have been no follow-ons until the 15th century.

Portuguese exploration

In the late 14th century, many maps appeared showing fictitious islands in the Atlantic. In this period, expanding commercial contacts linked the Mediterranean with communities along the Atlantic coast. In particular, Genoese, Florentine, and Venetian traders were active, and also religious groups seeking converts to Christianity. This expansion placed the Kingdom of Portugal in a strategic position. The seafaring Portuguese were eager to expand their realm and their influence.

In this context, Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) had an important role. He added his own financial support to the efforts of the Portuguese crown and financed the construction of new ships, establishing naval schools to harness seafaring knowledge and promoting new technologies and their use. Prince Henry is generally credited with motivating modern navigation and directing discoveries during the age of exploration.

Prince Henry hoped to establish communication by sea with India and the legendary realm of Prester John, thereby outflanking the hostile Muslim states in northern Africa and the Holy Land. He was Grand Master of the Military Order of Christ, whose program of exploration, discovery, and settlement was tailored for this dual purpose.

Prince Henry experimented with ships, navigational instruments, and maps, developing techniques that made oceanic travel possible. The Portuguese Atlantic islands were not unknown; a growing body of documents had shown that sailors were aware of the islands. But most important, in the words of Prince Henry's personal chronicler, is that the Prince "ordered [Portuguese navigators and captains] to find the islands", rather than just sending his fleets into the unknown to discover what they could.

The re-discovery

The exact date of this re-discovery of the Atlantic islands is not clear, though historical accounts indicate that the islands of Santa Maria and São Miguel were the first to be discovered by navigator Diogo de Silves around 1427.

One fact often debated is the origin of the name "Azores" used to identify the archipelago. By 1492, in the globe of Martin Behaim, the eastern and central group of islands were referred to as Insulae Azore ("Islands of the Azores"), while the islands of western group were called the Insulae Flores ("Islands of Flowers"). Similarly, older nautical charts had identified them as the Ilhas Afortunadas ("The Fortunate Islands") or Ilhas de São Brandão ("The Islands of Saint Brendan"). The use of mythical names in local naming became a theme; in São Miguel and Pico there are communities called Sete Cidades, on Terceira, a peninsula along the southern coast is referred to as Monte Brasil, and the name Mosteiros is used on both islands of São Miguel and Flores. There are also many examples of re-using names from island to island (for example, Cedros, São Pedro, Feteiras, or Calheta). Three theories have developed about the naming of the archipelago.

- The classical theory attributes the naming to the presence of diurnal birds of prey (some say goshawks, while others species of eagles), identified by Portuguese sailors at the time of discovery. But this theory has been discredited. The only bird of prey that nests in the archipelago is the common buzzard (Buteo buteo rothschildi), which was introduced during the period of colonization and settlement. Sailors may have confused existing migratory birds for such birds of prey, or used colloquial names and attributed them to these species, or some bird of prey species was present that became extinct since colonization;

- The naming of the islands may have been an homage by the discoverer Gonçalo Velho Cabral to Santa Maria of Açores, patron saint of the parish of Açores, in the municipality of Celorico da Beira, District of Guarda.

- "Açores" may have been a Portuguese variant of the Genovese or Florentine word azzurre or azzorre ("blue") and may refer to sailors' stories of the mythical "Ilhas Azuis". In fact, the blue-green vegetation on the islands of the Azores appears blue, even at a short distance. The Portuguese word for "blue" is similarly azul.

It is clear that after 1420, regular expeditions captained by Gonçalo Velho Cabral, Diogo de Silves, and other mariners began exploring to the west and south of continental Portugal. On 15 August 1432, men from a small sailing vessel with a dozen crew landed on the island that would bear the name Santa Maria (owing to its supposed day of its "rediscovery", the Assumption Day of the Virgin Mary).[21] With their beginnings in the eastern group of islands, the explorers advanced quickly into the rest of the archipelago, finally reaching the more westerly islands (Flores and Corvo) by about 1450 at a time when populations were already relatively large.[22] The first expeditions, apart from coastal observations and an occasional landing were limited, and in most cases involved the deliberate disembarking of herd animals (sheep, goats and/or cattle), pigs and chickens on the discovered islands, as a way of providing future settlers with some means of subsistence. There is also a reference to the purposeful settling of a group of slaves at the end of the 1430s, in the area of Povoação on the island of São Miguel.

Settlement

The "official" settlement of the archipelago began in Santa Maria, where the first settlement was constructed in the area of Baía dos Anjos (in the north of the island), and quickly moved to the southern coast (to the area that is now the modern town of Vila do Porto). Settlers quickly arrived from the provinces of Algarve and Alentejo as Gonçalo Velho's nephew and heir, João Soares de Albergaria, advertised and promoted settlement on the island. In the following centuries settlers from other European countries would arrive, most notably from Northern France and Flanders.

By 1440, other settlements had developed along the river-valleys and coastal inlets of São Miguel, Terceira, Faial, and Pico, supported by game animals and fishing. An abundance of potable water sources, along with fertile volcanic soils, made the islands attractive and easy to colonize, and the growing wheat market supported an export economy (along with various plant species that allowed the development of the dye industry in the colonies).

Christopher Columbus made an unplanned stop on Santa Maria while returning to Spain after his first voyage to America. His ship Niña was forced there by a storm. During the storm, all hands had vowed, if they were spared, to make a pilgrimage to the nearest church of Our Lady wherever they first made land. Anchoring at Santa Maria, the travelers were told by people onshore that a small shrine dedicated to Our Lady was nearby. Columbus sent half the crew ashore to fulfill their vow; he and the rest would go when the first group returned. But while the first crew members were saying their prayers at the shrine, they were taken prisoner by the island's captain, João de Castanheira, ostensibly out of fear that they were pirates. Castanheira commandeered their boat and rowed to Niña with several armed men, in an attempt to arrest Columbus. Columbus did not allow Castanheira to come aboard, and Castanheira announced that he did not believe or care who Columbus said he was, especially if he was indeed from Spain. After two days, Castanheira released the prisoners, having been unable to get confessions from them, and having been unable to capture his real target, Columbus. There are later claims that Columbus was also captured, but this is not backed up by Columbus's log book.[23]

The island of São Miguel was apparently populated by 1444. The population came mostly from the regions of Estremadura, Alentejo, and Algarve. The colonists spread themselves along the coastline in areas where conditions of accessibility and farming were best. The fertility of the Azores contributed to its population expansion, as the islands were soon exporting wheat to the Portuguese garrison in North Africa and of sugar cane and dyes to Flanders. Later oranges were grown and exported to the British Isles. The area was also frequently subjected to pirate attacks.

During these times Ponta Delgada became the capital. The first capital was Vila Franca do Campo, but when it was destroyed in a massive landslide caused by a powerful earthquake in 1522, Ponta Delgada assumed the position. It became the first city on the island in 1546.

Terceira Island was the third island to be discovered, its name literally meaning "Third Island". It was originally called the Island of Jesus Christ and was first settled in 1450. Graciosa Island was settled shortly afterward from settlers from Terceira.

Flores Island was discovered in the late summer of 1452 by the navigator Diogo de Teive and his son João de Teive. The island's charter passed to Fernão Telles de Meneses, who only populated the island with sheep in 1475. His widow, Dona Maria Vilhena, contracted the Flemish Willem van der Haegen to settle Flores. After some negotiation, D. Maria would cede the rights to the exploration of the islands to Van der Haegen, in exchange for monthly payments. Around 1478, Willem van der Haegen settled in Ribeira da Cruz, where he built homes, developed agriculture (primarily wheat), collected more woad species for export, and explored for tin, silver or other minerals (under the assumption that the islands were part of the mythic Ilhas Cassterides, the islands of silver and tin). Owing to the island's isolation and difficulties in communication his crops became difficult to export and van der Haegen left Flores in the late 1480s.

By 1504 the island's charter had passed to João Fonseca and settlers streamed through the port of Armoeira to the small hamlets. The island became permanently populated during the reign of King Manuel I, in 1510, by people from various regions of continental Portugal, but mainly from the northern provinces. The island became arable, and grain and vegetables were cultivated. According to the 2003 maternal DNA study of the Azores by Santos et al., people from Flores exhibit high genetic ancestry (~90%) with the Portuguese mainland. The 2006 paternal DNA study by Pacheco et al. confirms that around 60% of all Azorean paternal lines are correlated to those common in mainland Portugal.

Iberian Union

The residents of Terceira, who mostly settled in Porto Judeu and Praia da Vitória and along the coastline, took a brave stand against King Philip II of Spain upon his ascension to the Portuguese throne in 1580. They, along with most of the rest of the Azores, believed that António, Prior of Crato was the rightful successor, and defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Salga in 1581.

In 1583, Philip tried again at defeating the Azoreans. He sent his combined Iberian fleet to clear the French traders from the Azores, decisively hanging his prisoners-of-war from the yardarms and contributing to the "Black Legend". The Azores were the second-to-last part of the Portuguese empire to resist Philip's reign over Portugal (Macau being the last). The Azores were returned to Portuguese control with the end of the Iberian Union, not by the military efforts, as these were already in Restoration War efforts in the mainland, but by the people attacking the well-fortified Castilian garrison of Fortaleza de São João Baptista.

The Azores served as a port of call for the Spanish galleons during their occupation. In December 1640 the Portuguese monarchy was restored and the islands again became a Portuguese possession.

Liberal wars

The 1820 civil war in Portugal had strong repercussions in the Azores. In 1829, in Vila da Praia, the liberals won over the absolutists, making Terceira the main headquarters of the new Portuguese regime and also where the Council of Regency (Conselho de Regência) of Mary II of Portugal was established. In the second half of the 19th century, Azores played an important role in the rebirth of Portuguese cod fisheries in Terra Nova (Newfoundland). In fact, it was Azorean emigrants from the East coast returned to their homeland that taught the American dory fishing technique to Portuguese that started to catch again cod in the Grand Bank after the middle of the 19th century. Beginning in 1868, Portugal issued its stamps overprinted with "AÇORES" for use in the islands. Between 1892 and 1906, it also issued separate stamps for the three administrative districts of the time.

From 1836 to 1976, the archipelago was divided into three districts, equivalent (except in area) to those on the Portuguese mainland. The division was arbitrary, and did not follow the natural island groups, rather reflecting the location of each district capital on the three main cities (neither of each on the western group).

- Angra consisted of Terceira, São Jorge, and Graciosa, with the capital at Angra do Heroísmo on Terceira.

- Horta consisted of Pico, Faial, Flores, and Corvo, with the capital at Horta on Faial.

- Ponta Delgada consisted of São Miguel and Santa Maria, with the capital at Ponta Delgada on São Miguel.

20th century

During the Second World War, in 1943, representing a change in policy, the Portuguese dictator Salazar leased bases in the Azores to the British. Previously the Portuguese government had only allowed German U-boats and navy ships to refuel there.[24] This was a key turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic; by allowing the Allies to provide aerial coverage in the middle of the Atlantic (i.e. it closed the Mid-Atlantic Gap), it helped them hunt U-boats and protect convoys.

In 1944, American forces constructed a small and short-lived air base on the island of Santa Maria. In 1945, a new base was founded on the island of Terceira and is currently known as Lajes Field. It was founded in an area called Lajes, a broad, flat sea terrace that had been a farm. Lajes Field is a plateau rising out of the sea on the northeast corner of the island. This air force base is a joint American and Portuguese venture. Lajes Field has, and continues to support US and Portuguese military operations. During the Cold War, the US Navy P-3 Orion anti-submarine squadrons patrolled the North Atlantic for Soviet submarines and surface spy vessels. Since its inception, Lajes Field has been used for refuelling aircraft bound for Europe, and more recently, the Middle East. The US Army operates a small fleet of military ships in the harbor of Praia da Vitória, three kilometers southeast of Lajes Field. The airfield also has a small commercial terminal handling scheduled and chartered passenger flights from other islands in the archipelago, Europe, and North America.

Carnation Revolution

In 1976, following the Carnation Revolution of 1974, the Azores became an Autonomous Region within Portugal (Portuguese: Região Autónoma dos Açores), along with Madeira, when the new regional constitution was implemented and the Azorean districts were suppressed.

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Beazley (1897–1906, 1899:p. lxxii.)

- ↑ Babcock (1922: Ch. 3).

- ↑ Already both Plutarch (Life of Sertorius) and Pliny the Elder report that fishermen from Gades (Cadiz) routinely visited Atlantic islands to the southwest.

- ↑ Beazley (1897: vol.1, p. 465.)

- ↑ Beazley (1906: vol. 3, p. 532). Cortesão (1954 (1975))-

- ↑ De Las Casas, Bartolomé; Pagden, Anthony (8 September 1999). A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indias. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044562-5.

- ↑ Ashe, Thomas (1813). History of the Azores, or Western islands. Oxford University.

- ↑ These archaeological sites were first identified by Nuno Ribeiro (in 2010) during archeological visits to Corvo and Terceira, but further examination and dating were required to authenticate their validity.

- ↑ Lusa (5 March 2011), J.M.A. (ed.), Estruturas podem ter mais de dois mil anos: Monumentos funerários descobertos nos Açores (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: Correio da Manhã, retrieved 18 June 2011

- 1 2 Lusa (27 June 2011), A.O. Online (ed.), Estudos arqueológicos podem indicar presença prévia ao povoamento das ilhas (in Portuguese), Ponta Delgada (Azores), Portugal: Açoreana Oriental, retrieved 27 June 2011

- ↑ Yirka, Bob; Phys.org. "Evidence of people on the Azores archipelago 700 years earlier than thought". phys.org. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ↑ "Viking mice: Norse discovered Azores 700 years before Portuguese". CALS. 10 November 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ↑ "Vikings in paradise: Were the Norse the first to settle the Azores?". www.science.org. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ Amat di S. Filippo (1892: p. 534.); Mees (1901: p. 140.) Marcel (1887: p. 31.) suggests it may have already been hinted at in the Angelino Dulcert (1339) map, under the names St. Brendan, Primaria sive puellarum, Capraria and Canaria.

- ↑ Libro de Conoscimiento (1877 ed.: p. 50.)

- ↑ Babcock, p. 166.

- ↑ Cortesão (1954 (1975): p. 82.); Cortesão (1969: p. 67.)

- ↑ The 1341 expedition is related by Giovanni Boccaccio "De Canaria et insula reliquis, ultra Ispaniam, in occeano noviter repertis" (repr. in Monumenta Henricina, vol. I, pp. 202–06.)

- ↑ De la Roncière (1925: p. 4ff.); Magalhães Godinho (1962: p. 30); Cortesão (1954 (1975):pp. 90–91.)

- ↑ Fernández-Armesto (2007).

- ↑ Martin Behaim noted that two ships discovered the lands in 1431, and that a fleet of sixteen ships were sent to colonize the islands in 1432.

- ↑ The islands of Flores and Corvo were discovered by Pedro Vasquez de la Frontera and Diogo de Teive in 1452, during their return from voyages to the west, usually attributed to other discoveries or from fishing in the Terra dos Bacalhaus (the name attributed to the eastern coast of Newfoundland in Canada.

- ↑ Catz, Rebecca (1990). "Columbus in the Azores". Portuguese Studies. 6: 17–23. JSTOR 41104900.

- ↑ Petropoulos, Jonathan (1997). "The Role of Portugal – co-opting Nazi Gold", Dimensions, Vol 11, No 1.

- Sources

- Fructuoso, G. (1966). Saudades da Terra (Vol. 1–6), 1873. Instituto Cultural de Ponta Delgada, Ponta Delgada. ISBN 972-9216-70-3.

- Diffie, B. W.; Boyd C. Shafer; George Davison Winius (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580 – Europe and the World in the Age of Expansion (2nd Ed.). University of Minnesota. ISBN 0-8166-0782-6.

- Ashe, Thomas (1813). History of the Azores, or Western islands; containing an account of the government, laws, and religion, the manners, ceremonies, and character of the inhabitants: and demonstrating the importance of these valuable islands to the British Empire. London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones. online

- Babcock, W. H. (1922). Legendary islands of the Atlantic: a study in medieval geography. New York: American Geographical Society. online

- Beazley, C. R. (1897–1906). The Dawn of Modern Geography. London. vol. 1 (–900), vol. 2 (900–1260) vol. 3 (1260–1420)

- Beazley, C. Raymond (1899). "Introduction" in C. R. Beazley and E. Prestage, 1898–99, The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea, London: Halyut. v.2

- Cortesão, Armando (1954). The Nautical Chart of 1424 and the Early Discovery and Cartographical Representation of America. Coimbra and Minneapolis. (Portuguese trans. "A Carta Nautica de 1424", published in 1975, Esparsos, Coimbra. vol. 3)

- Cortesão, Armando (1969). History of Portuguese Cartography. Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar

- Fernández-Armesto, F. (2007). Before Columbus: exploration and colonisation from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic 1229–1492. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Magalhães Godinho, V. (1962). A Economia dos descobrimentos henriquinos. Lisbon: Sá da Costa

- Mees, J. (1901). Histoire de la découverte des Îles Açores et de l'origine de leur dénomination d'Îles Flamandes Ghent: Vuylsteke online

- Petrus Amat di S. Filippo (1892). "I veri Scopritori delle Isole Azore", Bollettino della Società geografica italiana, Vol. 29, pp. 529–41.

- Roncière, C. de la (1925). La découverte de l'Afrique au Moyen Âge: Le Périple du continent, Vol. II. Cairo: Société Royale de Géographie d'Égypte