| History of Kazakhstan |

|---|

|

Kazakhstan, the largest country fully within the Eurasian Steppe, has been a historical crossroads and home to numerous different peoples, states and empires throughout history. Throughout history, peoples on the territory of modern Kazakhstan had nomadic lifestyle, which developed and influenced Kazakh culture.

Human activity in the region began with the extinct Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus one million–800,000 years ago in the Karatau Mountains and the Caspian and Balkhash areas. Neanderthals were present from 140,000 to 40,000 years ago in the Karatau Mountains and central Kazakhstan. Modern Homo sapiens appeared from 40,000 to 12,000 years ago in southern, central and eastern Kazakhstan. After the end of the last glacial period (12,500 to 5,000 years ago) human settlement spread across the country and led to the extinction of the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros. Hunter-gatherer communes invented bows and boats and used domesticated wolves and traps for hunting.

The Neolithic Revolution was marked by the appearance of animal husbandry and agriculture, giving rise to the Atbasar,[1] Kelteminar,[1] Botai,[1] and Ust-Narym cultures.[1] The Botai culture (3600–3100 BC) is credited with the first domestication of horses, and ceramics and polished-stone tools also appeared during this period. The fourth and third millennia witnessed the beginning of metal production, the manufacture of copper tools and the use of casting molds. In the second millennium BC ore mining developed in central Kazakhstan.

The change in climate forced the massive relocation of populations in and out of the steppe belt. The dry period that lasted from the end of the second millennium to the beginning of the 1st millennium BC caused the depopulation of the arid belts and river-valley oasis areas, the populations moving north to the forest steppe.

.png.webp)

After the end of the arid period at the beginning of the first millennium BC nomadic populations migrated into Kazakhstan from the west and the east, repopulating abandoned areas. They included several Indo-Iranians, often known collectively as the Saka.[2][3]

In the 13th century, Kazakhstan was conquered by the Mongol Empire and controlled by the Golden Horde. After the Golden Horde declined, the Uzbek Khanate broke away from it. In 1465, Kazakh Khanate gained its independence from Uzbeks. Portions of the country began to be annexed by the Russian Empire in the 18th century, the remainder gradually being absorbed into Russian Turkestan beginning in 1867. The modern Republic of Kazakhstan became a political entity during the 1930s Soviet subdivision of Russian Turkestan.

Prehistory

Humans have inhabited Kazakhstan since the Lower Paleolithic, generally pursuing the nomadic pastoralism for which the region's climate and terrain are suitable.[4] Prehistoric Bronze Age cultures that extended into the region include the Srubna, the Afanasevo and the Andronovo. Between 500 BC and 500 AD Kazakhstan was home to the Saka and the Huns, early nomadic warrior cultures.

According to the Journal of Archaeological Science, in July 2020 scientists from South Ural State University studied two Late Bronze Age horses with the aid of radiocarbon dating from Kurgan 5 of the Novoilinovsky 2 cemetery in the Lisakovsk city in the Kostanay region. Researcher Igor Chechushkov indicated that the Andronovites were riding horses several centuries earlier than many researchers had previously assumed. Among the horses investigated, the stallion was nearly 20 years old and the mare was 18 years old. According to scientists, animals were buried with the person they accompanied throughout their lives, and they were used not only for food but also for harnessing vehicles and riding.[5][6][7]

Turkic people migrated into Kazakhstan

At the beginning of the first millennium the steppes east of the Caspian were inhabited and settled by a variety of peoples, mainly nomads speaking Indo-European and Uralic languages, including the Alans, Aorsi, Budini, Issedones/Wusun, Madjars, Massagetae and Sakas. The names, relations between and constituents of these peoples were sometimes fluid and interchangeable. Some of them formed states, including Yancai (northwest of the Aral Sea) and Kangju in the east. Over the course of several centuries the area became dominated by Turkic and other exogenous languages, which arrived with nomad invaders and settlers from the east.

Following the entry of the Huns many of the previous inhabitants migrated westward into Europe or were absorbed by the Huns. The focus of the Hun Empire gradually moved westward from the steppes into Eastern Europe.

For a few centuries events in the future Kazakhstan are unclear and frequently the subject of speculation based on mythic or apocryphal folk tales popular among various peoples that migrated westward through the steppes.

From the middle of the 2nd century the Yueban – an offshoot of the Xiongnu and therefore possibly connected to the Huns – established a state in far-eastern Kazakhstan.

Over the next few centuries peoples such as the Akatziri, Avars (known later as the Pannonian Avars; not to be confused with the Avars of the Caucasus), Sabirs and Bulgars migrated through the area and into the Caucasus and Eastern Europe.

By the beginning of the 6th century the proto-Mongolian Rouran Khaganate had annexed areas that were later part of east Kazakhstan.

.PNG.webp)

The Göktürks, a Turkic people formerly subject to the Rouran, migrated westward, pushing the remnants of the Huns west and southward. By the mid-6th Century, the First Turkic Khaganate was established.A few decades later, a civil war resulted in the khaganate being split, and establishment of the Eastern Turkic Khaganate and Western Turkic Khaganate. In 630 and 659, the Eastern and Western Turkic Khaganate were invaded and conquered by the Tang China. Towards the end of the 7th century, the two states were reunited in the Second Turkic Khaganate. However, the khaganate began to fragment only a few generations later.

In 766 the Oghuz Yabgu State (Oguz il) was founded, with its capital in Jankent, and came to occupy most of the later Kazakhstan. It was founded by the Oghuz Turks refugees from the neighbouring Turgesh Kaganate. The Oghuz lost a struggle with the Karluks for control of Turgesh, other Oguz clans migrated from the Turgesh-controlled Zhetysu to the Karatau Mountains and the Chu valley, in the Issyk Kul basin.

Cuman-Kipchak period

_eng.png.webp)

In the eighth and ninth centuries, portions of southern Kazakhstan were conquered by Arabs who introduced Islam. The Oghuz Turks controlled western Kazakhstan from the ninth through the 11th centuries; and Turkic peoples of Kipchaks and Kimaks, controlled the east at roughly the same time. In turn the Cumans controlled western Kazakhstan from around the 12th century until the 1220s. Since then, those vast lands are came to be known as Dashti-Kipchak, or the Kipchak Steppe.[4]

During the ninth century the Qarluq confederation formed the Qarakhanid state, which conquered Transoxiana (the area north and east of the Oxus River, the present-day Amu Darya). Beginning in the early 11th century, the Qarakhanids fought constantly among themselves and with the Seljuk Turks to the south. The Qarakhanids, who had converted to Islam, were conquered in the 1130s by the Kara-Khitan (a Mongol people who moved west from North China). In the mid-12th century an independent state of Khorazm along the Oxus River broke away from the weakening Karakitai, but the bulk of the Kara-Khitan lasted until the Mongol invasion of Genghis Khan from 1219 to 1221.[4]

Mongol Empire

During Mongol advancement into Desht-i-Kipchak lands, some Cuman-Kipchak leaders fought the advancing Mongols, but most joined them and came to constitute most of the military force of the Mongol Empire.

After the partitioning of the empire in the latter 13th century, the western Mongol state called Golden Horde broke away from the unified empire. Kazakhstan was controlled by Golden Horde for more than 200 years.

During Uzbeg Khan's rule (1312–41), Islam was adopted as a state religion.

According to the latest research of population genetics, mainly of autosomal markers and Y-chromosome polymorphism, it is believed that during the 13th to 15th centuries that the Kazakh ethnicity emerged.[8]

Kazakh Khanate (1465–1847)

After the dissolution of Golden Horde, on most of the territory of modern Kazakhstan, the Uzbek Khanate was formed. Country under Abu'l-Khayr Khan, was weak and the government was corrupt. Two children of Barak Khan, Janibek and Kerei Khan gathered Kazakh people to Jetysu, where they founded Independent Kazakh Khanate.

During the reign of Kasym Khan (1511–1523), the khanate expanded considerably. Numerous victories in wars against neighbouring countries made the Khanate's reputation and country well known even in Western Europe. The first Kazakh code of laws, Qasym Khannyn Qasqa Zholy (Bright Road of Kasym Khan), was also established in 1520.

Between 1522 and 1538, the Khanate experienced its first civil war.

The khanate is described in historical texts such as the Tarikh-i-Rashidi (1541–1545) by Muhammad Haidar Dughlat[9] and Zhamigi-at-Tavarikh (1598–1599) by Kadyrgali Kosynuli Zhalayir.

In 1643, the Kazakh-Dzungar wars unfolded and became a disaster for the Kazakhs. The Khanate's population was divided into three tribes, called juzes: senior, middle and junior. During the reign of Ablai Khan (1771–1781), he united all Kazakhs to fight the Dzungars.

In the 19th century, Russian Empire showed interest in Afghanistan and to reach it, Russia invades Kazakh lands. To confront Russian invasion, the last Khan - Kenesary Khan organized riots, starting from 1837 and ending in 1847 due to the execution of Kenesary.

Russian Empire (1731–1917)

Russian traders and soldiers began to appear on the northwestern edge of Kazakh territory in the 17th century, when Cossacks established forts which later became the cities of Yaitsk (modern Oral) and Guryev (modern Atyrau). The Russians were able to seize Kazakh territory because the khanates were preoccupied by the Zunghar Oirats, who began to move into the region from the east in the late 16th century. Forced westward, the Kazakhs were caught between the Kalmyks and the Russians.

First half of the 1700s, was marked by the surge of conflicts and wars with Dzungars. In 1730 Abul Khayr, a khan of the Lesser Horde, sought Russian assistance. Although Khayr's intent was to form a temporary alliance against the stronger Kalmyks, the Russians gained control of the Lesser Horde. They conquered the Middle Horde by 1798, but the Great Horde remained independent until the 1820s (when the expanding Kokand khanate to the south forced the Great Horde khans to accept Russian protection, which seemed to them the lesser of two evils).

The Russian Empire started to integrate the Kazakh steppe. Between 1822 and 1848, the three main Kazakh Khans of the Lesser, Middle and Great Horde were suspended. Russians built many forts to control the conquered territories. Moreover, Russian settlers were provided with land, whereas nomadic tribes had less area available to drive their herds and flocks. Many of the nomadic tribes were forced to adopt poor and sedentary lifestyles. Because of the Russian Empire policy, between 5 and 15 per cent of the population of Kazakh Steppe were immigrants.[11]

Nineteenth-century colonization of Kazakhstan by Russia was slowed by rebellions and wars, such as uprisings led by Isatay Taymanuly and Makhambet Utemisuly from 1836 to 1838 and the war led by Eset Kotibaruli from 1847 to 1858. In 1863, the Russian Empire announced a new policy asserting the right to annex troublesome areas on its borders. This led immediately to the conquest of the remainder of Central Asia and the creation of two administrative districts: the General-Gubernatorstvo (Governor-Generalships) of Russian Turkestan and the Steppes. Most of present-day Kazakhstan, including Almaty (Verny), was in the latter district.[12]

During the nineteenth century, Kazakhs had remarkable numeracy level, which increased from approximately 72% in 1820 to approximately 88% in 1880. In the first part of the century, Kazakhs were even more numerate than Russians were. However, in that century, Russia conquered many countries and experienced a human capital revolution, which led to a higher numeracy afterwards. Nevertheless, the numeracy of Kazakhs was still higher than other Central Asian nations, which are nowadays referred to as Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. There could be several reasons for this striking early numeracy level. First and foremost, the settler share could explain part of this, albeit Russians were a minority in the Kazakh steppe. Secondly, the relatively good nutritional situation in Kazakhstan. Protein malnutrition that plagued many other populations of Central Asian nations was absent in Kazakhstan. Moreover, Russian settlers of the 1870s and 1880s might have simulated so-called contact learning. Kazakhs started to invest more in human capital because they observed that Russians were successful in that area.[13]

During the early 19th century, the Russian forts began to limit the area over which the nomadic tribes could drive their herds and flocks. The final disruption of nomadism began in the 1890s, when many Russian settlers were introduced into the fertile lands of northern and eastern Kazakhstan.[12]

In 1906 the Trans-Aral Railway between Orenburg and Tashkent was completed, facilitating Russian colonisation of the fertile lands of Zhetysu. Between 1906 and 1912, more than a half-million Russian farms were established as part of reforms by Russian Minister of the Interior Petr Stolypin; the farms pressured the traditional Kazakh way of life, occupying grazing land and using scarce water resources. The administrator for Turkestan (current Kazakhstan), Vasile Balabanov, was responsible for Russian resettlement at this time.

Starving and displaced, many Kazakhs joined in the Basmachi movement against conscription into the Russian imperial army ordered by the tsar in July 1916 as part of the war effort against Germany in World War I. In late 1916, Russian forces suppressed the widespread armed resistance to the taking of land and conscription of Central Asians. Thousands of Kazakhs were killed, and thousands more fled to China and Mongolia.[12] Many Kazakhs and Russians fought the Communist takeover, and resisted its control until 1920.

Alash and Turkestan Autonomy

_Autonomy.svg.png.webp)

Alash orda 1917–1920

In the second half of the 20th century,second half of the 20th century Russia started building schools in Kazakhstan. It led to the formation of elite in Kazakh society. Most educated Kazakhs were members of Constitutional Democratic Party, but after it fractioned, Kazakh elite formed new party named after a legendary founder of the Kazakh people—Alash. The party's goal was to found an independent democratic Kazakh state. The party managed to form same-named Orda, which lasted until 1920, when Bolsheviks banned the party.[14]

The territory of Alash orda covered most of modern territories of Kazakhstan excluding southern regions.

Turkestan orda

The Turkestan orda or Kokand Autonomy, was an unrecognized state in Central Asia that existed at the beginning of the Russian Civil War. It was formed on 27 November 1917[lower-alpha 1] and existed until 22 February 1918. It was a secular republic, headed by a president.

Soviet Union (1920–1991)

The Kirghiz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, established in 1920, was renamed the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic in 1925 when the Kazakhs were officially distinguished from the Kyrgyz by the Soviet government. Although the Russian Empire recognized the ethnic difference between the groups, it called them both "Kirghiz" to avoid confusion between the terms "Kazakhs" and Cossacks (both names originating from the Turkic "free man").[15][16]

In 1925 the republic's original capital, Orenburg, was reincorporated into Russian territory and Kyzylorda became the capital until 1929. Almaty (known as Alma-Ata during the Soviet period), a provincial city in the far southeast, became the new capital in 1929. In 1936, the territory was officially separated from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and made a Soviet republic: the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. With an area of 2,717,300 km2 (1,049,200 sq mi), the Kazakh SSR was the second-largest republic in the Soviet Union.

Two famines

First Kazakh famine started in 1919 during Russian Civil War. Amount of livestock in Kazakhstan decreased from 30 million to 16 million, which left almost million people starving due to the civil war. Apart from a famine, Kazakhstan suffered from stopping of all factories.

From 1929 to 1934, when Joseph Stalin was trying to collectivize agriculture, Kazakhstan endured repeated famine called Asharshylyk similar to the Holodomor[17] in Ukraine; in both republics and the Russian SFSR,[18] peasants slaughtered their livestock in protest against Soviet agricultural policy.[19] During that period, over one million residents[20] and 80 percent of the republic's livestock died. Thousands more tried to escape to China, although most starved in the attempt. According to Robert Conquest, "The application of party theory to the Kazakhs, and to a lesser extent to the other nomad peoples, amounted economically to the imposition by force of an untried stereotype on a functioning social order, with disastrous results. And in human terms it meant death and suffering proportionally even greater than in the Ukraine".[21]

Repressions

During the 1930s, the Soviet government built Gulags across the Union. There were 11 concentration camps built in Kazakhstan, the most well known being ALZhIR.

NKVD Order 00486 of 15 August 1937 marked the beginning of mass repression against ChSIR: members of the families of traitors to the Motherland (Russian: ЧСИР: члены семьи изменника Родины). The order gave the right to arrest without evidence of guilt, and sent women political-prisoners to the camps for the first time. In a few months, female "traitors" were arrested and sentenced to from five to eight years in prison.[22] More than 18,000 women were arrested, and about 8,000 served time in ALZhIR – the Akmolinsk Camp of Wives of Traitors to the Motherland (Russian: Акмолинский лагерь жён изменников Родины (А. Л. Ж. И. Р.)). They included the wives of statesmen, politicians and public figures in the then Soviet Union, including the wives of the former members of the Alash movement.[23] After the closure of the prisons in 1953, it was reported that 1,507 of the women gave birth as a result of being raped by the guards.[24]

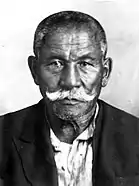

During Soviet rule most of former members of Alash started working on translating textbooks for newly building schools, since most Kazakhs still weren't educated. Some of former members joined Communist Party, but still elite protested several politics of Soviet government, like collectivization which led to the artificial famine of 1930–33. The Soviet Government attempted to oppress and imprison many of the Kazakh elites. Due to the harsh treatment and conditions in the Kazakh gulags, imprisoned former Alash members experienced accelerated aging over the span of just a few years. This can be observed via photos taken of them before their imprisonment, and gulag mugshots taken before their executions.

World War II

Through the lens of the front lines and the home front, Roberto Carmack argues that World War II spurred Kazakhstan’s larger integration into the Soviet Union. However the war experience simultaneously worsened and reinforced ethnic tensions and social disparities. Even in the Soviet Union’s darkest hours ethnic chauvinism could overrule matters of national security. The Kremlin's propaganda efforts dirfected at soldiers and civilians, combined with military service and exposure to other parts of the USSR, Sovietized the Kazakh populace and the Kazakh SSR. The war made Kazakhstan more Soviet, but also strengthened its colonial status as a supplier of raw materials and manpower for the war effort, and solidified the hierarchy led by Russia in the USSR.[25]

Internal Soviet migration

Many Soviet citizens from the western regions of the USSR and a great deal of Soviet industry relocated to the Kazakh SSR during World War II, when Axis armies captured or threatened to capture western Soviet industrial centres. Groups of Soviet citizens including Crimean Tatars, German, and Muslims from the North Caucasus were deported to the Kazakh SSR during the war. The Kremlin feared that they would collaborate with the Nazi invaders. Many Poles from eastern Poland were also deported to the Kazakh SSR, and local people shared their food with the new arrivals.[14]

Many more non-Kazakhs arrived between 1953 and 1965, during the Virgin Lands Campaign of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (in office 1958–1964). That program saw huge tracts of Kazakh SSR grazing land cultivated for wheat and other cereal grains. More settlement occurred in the late 1960s and 1970s, when the Soviet government paid bonuses to workers participating in a program to relocate Soviet industry closer to Central Asia's coal, gas, and oil deposits. By the 1970s the Kazakh SSR was the only Soviet republic in which those of eponymous nationality was a minority, due to immigration and the decimation of the nomadic Kazakh population.[14]

The Kazakh SSR played industrial and agricultural roles in the centrally-controlled Soviet economic system, with coal deposits discovered during the 20th century promising to replace depleted fuel-reserves in the European territories of the USSR. The distance between the European industrial centres and the Kazakh coal-fields posed a formidable problem – only partially solved by Soviet efforts to industrialize Central Asia. This left the Republic of Kazakhstan a mixed legacy after 1991: a population of nearly as many Russians as Kazakhs; a class of Russian technocrats necessary to economic progress but ethnically unassimilated, and a coal- and oil-based energy industry whose efficiency is limited by inadequate infrastructure.[26]

Republic of Kazakhstan (1991–present)

On 16 December 1986, the Soviet Politburo dismissed longtime General Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan Dinmukhamed Konayev. His successor was the non-Kazakh Gennady Kolbin from Ulyanovsk, Russia, which triggered demonstrations protesting the move. The protests were violently suppressed by the authorities, and "between two and twenty people lost their lives, and between 763 and 1137 received injuries. Between 2,212 and 2,336 demonstrators were arrested".[27] When Kolbin prepared to purge the Communist Youth League he was halted by Moscow, and in September 1989 he was replaced with the Kazakh Nursultan Nazarbayev.

In June 1990 Moscow declared the sovereignty of the central government over Kazakhstan, forcing Kazakhstan to make its own statement of sovereignty. The exchange exacerbated tensions between the republic's two largest ethnic groups, who at that point were numerically about equal. In mid-August, Kazakh and Russian nationalists began to demonstrate around Kazakhstan's parliament building in an attempt to influence the final statement of sovereignty being drafted; the statement was adopted in October.

Nazarbayev Era

Like other Soviet republics at that time, Parliament named Nazarbayev its chairman and converted his chairmanship to the presidency of the republic. Unlike the leaders of the other Soviet republics (especially the independence-minded Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), Nazarbayev remained committed to the Soviet Union during the spring and summer of 1991 largely because he considered parts of USSR too interdependent economically to be able to survive independently. However, he also fought to control Kazakhstan's mineral wealth and industrial potential.

This objective became particularly important after 1990, when it was learned that Mikhail Gorbachev had negotiated an agreement with the American Chevron Corporation to develop Kazakhstan's Tengiz oil field; Gorbachev did not consult Nazarbayev until the talks were nearly completed. At Nazarbayev's insistence, Moscow surrendered control of the republic's mineral resources in June 1991 and Gorbachev's authority crumbled rapidly throughout the year. Nazarbayev continued to support him, urging other republic leaders to sign a treaty creating the Union of Sovereign States which Gorbachev had drafted in a last attempt to hold the Soviet Union together.

Because of the August 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt against Gorbachev, the union treaty was never implemented. Ambivalent about Gorbachev's removal, Nazarbayev did not condemn the coup attempt until its second day. However, he continued to support Gorbachev and some form of union largely because of his conviction that independence would be economic suicide.

At the same time, Nazarbayev began preparing Kazakhstan for greater freedom or outright independence. He appointed professional economists and managers to high positions, and sought advice from foreign development and business experts. The outlawing of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan (CPK) which followed the attempted coup permitted Nazarbayev to take nearly complete control of the republic's economy, more than 90 percent of which had been under the partial (or complete) direction of the Soviet government until late 1991. He solidified his position by winning an uncontested election for president in December 1991.

A week after the election, Nazarbayev became the president of an independent state when the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus signed documents dissolving the Soviet Union. He quickly convened a meeting of the leaders of the five Central Asian states (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan), raising the possibility of a Turkic confederation of former republics as a counterweight to the Slavic states of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus in whatever federation might succeed the Soviet Union. This move persuaded the three Slavic presidents to include Kazakhstan among the signatories of a recast document of dissolution. Kazakhstan's capital lent its name to the Alma-Ata Protocol, the declaration of principles of the Commonwealth of Independent States. On 16 December 1991, five days before the declaration, Kazakhstan became the last of the republics to proclaim its independence.

The republic has followed the same general political pattern as the other four Central Asian states. After declaring its independence from a political structure dominated by Moscow and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) until 1991, Kazakhstan retained the governmental structure and most of the leadership which had held power in 1990. Nazarbayev, elected president of the republic in 1991, remained in undisputed power five years later.

He took several steps to ensure his position. The constitution of 1993 made the prime minister and the Council of Ministers responsible solely to the president, and a new constitution two years later reinforced that relationship. Opposition parties were limited by legal restrictions on their activities. Within that framework, Nazarbayev gained substantial popularity by limiting the economic shock of separation from the Soviet Union and maintaining ethnic harmony in a diverse country with more than 100 different nationalities.

In December 1994 Nazarbayev signed the Budapest Memorandum along with Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States acting as guarantors and thereby denuclearized the nation. The leaders of Ukraine and Belarus also signed similar documents in a joint ceremonial event in Patria Hall at the Budapest Convention Center.[28][29][30]

In 1997 Kazakhstan's capital was moved from Almaty to Astana, and homosexuality was decriminalized the following year.[31]

After Nazarbayev

In March 2019, President Nursultan Nazarbayev resigned 29 years after taking office. However, he continued to lead the influential security council and held the formal title Leader of the Nation.[32] Kassym-Jomart Tokayev succeeded Nazarbayev as the President of Kazakhstan. His first official act was to rename the capital from Astana to Nur-Sultan after his predecessor.[33] In June 2019, the new president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, won Kazakhstan's presidential election.[34]

In January 2022, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev took over as head of the powerful Security Council, removing Nazarbayev from the post, after violent protests triggered by fuel price.[35] President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev later proposed constitutional amendments aimed at limiting his power and stripping Nazarbayev of his formal title Leader of the Nation.[36][37][38] Kazakhs later voted in the 2022 Kazakh constitutional referendum approving of the constitutional amendments.[39][40] In September 2022, the name of the country's capital was changed back to Astana from Nur-sultan.[41]

Relationship with Russia

During the mid-1990s, although Russia remained the most important sponsor of Kazakhstan in economic and national security matters Nazarbayev supported the strengthening of the CIS. As sensitive ethnic, national-security and economic issues cooled relations with Russia during the decade, Nazarbayev cultivated relations with China, the other Central Asian nations, and the West; however, Kazakhstan remains principally dependent on Russia. The Baikonur Cosmodrome, built during the 1950s for the Soviet space program, is near Tyuratam and the city of Baikonur was built to accommodate the spaceport.

Relationship with the US

Kazakhstan also maintains good relations with the United States. The country is the US's 78th-largest trading partner, incurring $2.5 billion in two-way trade, and it was the first country to recognize Kazakhstan after independence. In 1994 and 1995, the US worked with Kazakhstan to remove all nuclear warheads after the latter renounced its nuclear program and closed the Semipalatinsk Test Sites; the last nuclear sites and tunnels were closed by 1995. In 2010, US President Barack Obama met with Nazarbayev at the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington, DC and discussed intensifying their strategic relationship and bilateral cooperation to increase nuclear safety, regional stability, and economic prosperity.

See also

Notes

- ↑ November 28 in Kazakh-language sources.

References

- 1 2 3 4 The Cambridge World Prehistory. University of Cambridge. June 2014. ISBN 9780521119931.

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road : a history of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2. OCLC 229467524. "Modern scholars have mostly used the name Saka to refer to Iranians of the Eastern Steppe and Tarim Basin"

- ↑ Dandamayev, M. A. (1994). "Media and Achaemenid Iran". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. UNESCO. pp. 35–59. ISBN 9231028464. Retrieved 29 May 2015. "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. Those tribes spoke Iranian languages and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."(p. 37)

- 1 2 3 Curtis, Glenn E. "Early Tribal Movements". Kazakstan: A Country Study. United States Government Publishing Office for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Chechushkov, Igor V.; Usmanova, Emma R.; Kosintsev, Pavel A. (1 August 2020). "Early evidence for horse utilization in the Eurasian steppes and the case of the Novoil'inovskiy 2 Cemetery in Kazakhstan". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 32: 102420. Bibcode:2020JArSR..32j2420C. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102420. ISSN 2352-409X. S2CID 225452095.

- ↑ "Russian Scientists Have Discovered the Most Ancient Evidence of Horsemanship in the Bronze Age - South Ural State University". www.susu.ru. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ↑ "The most ancient evidence of horsemanship in the bronze age". phys.org. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ↑ Sabitov Zh. M., Zhabagin M. K. Population genetics of Kazakh ethnogenesis Archived 23 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "2017. Vol. 5, no. 4. Nurlan Kenzheakhmet". Золотоордынское обозрение. 19 December 2017. doi:10.22378/2313-6197.2017-5-4.770-785. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ↑ Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press, pp. 45–47, ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 9781107507180.

- 1 2 3 Curtis, Glenn E. "Russian Control". Kazakstan: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 9781107507180.

- 1 2 3 Curtis, Glenn E. "In the Soviet Union". Kazakstan: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Olcott, Martha Brill (1995). The Kazakhs (2nd ed.). p. 4.: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8179-9351-7. OCLC 32547109.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (1995). Histoire des Cosaques [History of the Cossacks] (in French). Lyon, FR: Terre Noire. p. 38.

- ↑ Kazakhstan: The Forgotten Famine Archived 29 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe, 28 December 2007

- ↑ Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet collectivization and the terror-famine, Oxford University Press US, 1987 p.196.

- ↑ Robert Conquest, The harvest of sorrow, p.193

- ↑ Timothy Snyder, 'Holocaust:The Ignored Reality,’ in New York Review of Books 16 July 2009 pp.14–16, p.15

- ↑ Conquest, Robert, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine; Chapter 9 p.198, Central Asia and the Kazakh Tragedy (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press in Association with the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies & London: Century Hutchison, 1986) ISBN 0-09-163750-3

- ↑ "alzhir camp". www.alzhir.kz. 2014. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Қазақ энциклопедиясы. Glavnai︠a︡ redakt︠s︡ii︠a︡ "Qazaq ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡sy". 2004. ISBN 9965-9389-9-7.

- ↑ Lills, Joanna; Trilling, David (6 August 2009). "The forgotten women of the Gulag". Eurasianet. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ Roberto J. Carmack, Kazakhstan in World War II: Mobilization and Ethnicity in the Soviet Empire (University Press of Kansas, 2019) online review

- ↑ "History of Kazakhstan". Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Hiro, Dilip, Between Marx and Muhammad: The Changing Face of Central Asia, Harper Collins, London, 1994,

- ↑ Potter, William C. (April 1995). "The Politics of Nuclear Renunciation: The Cases of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine" (PDF). Occasional Papers. The Henry L. Stimson Center (22).

- ↑ "1994 Public Papers 2146 - Remarks at the Denuclearization Agreements Signing Ceremony in Budapest". Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: William J. Clinton (1994, Book II). 5 December 1994.

- ↑ "Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with the Republic of Kazakhstan's Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons". UNTERM portal.

- ↑ "Where is it illegal to be gay?". BBC News. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Kazakh leader Nazarbayev resigns after three decades". BBC News. 19 March 2019.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan renames capital as new president takes office". France 24. 20 March 2019.

- ↑ "Nazarbayev protégé wins Kazakhstan elections marred by protests". France 24. 10 June 2019.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan's Nazarbayev handed over security council job on his own will: Spokesman". www.aa.com.tr.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan president proposes reforms to limit his powers". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ "What's in Kazakhstan's Constitutional Referendum?". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan: Nazarbayev to lose his place in constitution | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ "Kazakh President Tokayev promises reform after referendum win". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan holds referendum to amend constitution". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ agencies, Staff and (14 September 2022). "Kazakhstan to change name of capital from Nur-sultan back to Astana". the Guardian.

Further reading

- Abylkhozhin, Zhulduzbek, et al. eds. Stalinism in Kazakhstan: History, Memory, and Representation (2021). excerpt

- Adams, Margarethe. Steppe Dreams: Time, Mediation, and Postsocialist Celebrations in Kazakhstan (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020).

- Cameron, Sarah. The hungry steppe: Famine, violence, and the making of Soviet Kazakhstan (Cornell University Press, 2018). online review

- Carmack, Roberto J. Kazakhstan in World War II: Mobilization and Ethnicity in the Soviet Empire (University Press of Kansas, 2019) online review

- Hiro, Dilip. Inside Central Asia : a political and cultural history of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Iran (2009) online

- Kaşıkçı, Mekhmet Volkan. "Living under Stalin's Rule in Kazakhstan." Kritika 23.4 (2022): 905-923. excerpt

- Kassenova, Togzhan. Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb (Stanford University Press, 2022).

- Pianciola, Niccolò. "Nomads and the State in Soviet Kazakhstan." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History (2019), online.

- Pianciola, Niccolò. "Sacrificing the Qazaqs: The Stalinist Hierarchy of Consumption and the Great Famine of 1931–33 in Kazakhstan." Journal of Central Asian History 1.2 (2022): 225-272. online

- Ramsay, Rebekah. "Nomadic Hearths of Soviet Culture: ‘Women’s Red Yurt’ Campaigns in Kazakhstan, 1925–1935." Europe-Asia Studies 73.10 (2021): 1937-1961.

- Toimbek, Diana. "Problems and perspectives of transition to the knowledge-based economy in Kazakhstan." Journal of the Knowledge Economy 13.2 (2022): 1088-1125.

- Tredinnick, Jeremy. An illustrated history of Kazakhstan : Asia's heartland in context (2014), popular history. online

External links

- History of Kazakhstan at expat.nursat.kz

- at britannica.com

- Origins of Kazakhs and Ozbeks

- History of Kazakhstan