| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism |

|---|

Chinese: "Buddha" |

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

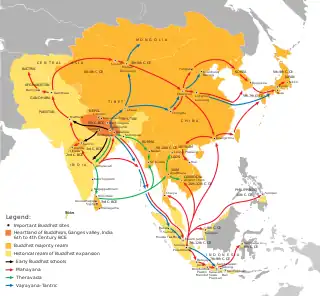

The history of Chinese Buddhism begins in the Han dynasty, when Buddhism first began to arrive via the Silk Road networks (via overland and maritime routes). The early period of Chinese Buddhist history saw efforts to propagate Buddhism, establish institutions and translate Buddhist texts into Chinese. The effort was led by non-Chinese missionaries from India and Central Asia like Kumarajiva and Paramartha well as by great Chinese pilgrims and translators like Xuanzang.

After the Han era, there was a period in which Buddhism became more Sinicized and new unique Chinese traditions of Buddhism arose, like Pure Land, Chan, Tiantai and Huayan. These traditions would also be exported to Korea, Japan and Vietnam and they influenced all of East Asian Buddhism.

Though Buddhism suffered numerous setbacks during the modern era (such as the widespread destruction of temples during the Taiping Rebellion and Cultural Revolution), it also experienced periods of reform and revival. Buddhism is currently the largest institutionalized religion in mainland China.[1]

Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE)

Various legends tell of the presence of Buddhism on Chinese soil in very ancient times. While the scholarly consensus is that Buddhism first came to China in the first century CE during the Han dynasty, through missionaries from India,[3] it is not known precisely when Buddhism entered China.

Generations of scholars have debated whether Buddhist missionaries first reached Han China via the maritime or overland routes of the Silk Road. The maritime route hypothesis, favored by Liang Qichao and Paul Pelliot, proposed that Buddhism was originally practiced in southern China, the Yangtze River, and Huai River region. On the other hand, it must have entered from the northwest via the Gansu corridor to the Yellow River basin and the North China Plain in the course of the first century CE. The scene becomes clearer from the middle of the second century onward, when the first known missionaries started their translation activities in the capital, Luoyang. The Book of the Later Han records that in 65 CE, the prince Liu Ying of Chu (present-day Jiangsu) "delighted in the practices of Huang-Lao Daoism" and had both Buddhist monks and laypeople at his court who presided over Buddhist ceremonies.[4] The overland route hypothesis, favored by Tang Yongtong, proposed that Buddhism disseminated through Central Asia – in particular, the Kushan Empire, which was often known in ancient Chinese sources as Da Yuezhi ("Great Yuezhi"), after the founding tribe. According to this hypothesis, Buddhism was first practiced in China in the Western Regions and the Han capital Luoyang (present-day Henan), where Emperor Ming of Han established the White Horse Temple in 68 CE.

In 2004, Rong Xinjiang, a history professor at Peking University, reexamined the overland and maritime hypotheses through a multi-disciplinary review of recent discoveries and research, including the Gandhāran Buddhist Texts, and concluded:

The view that Buddhism was transmitted to China by the sea route comparatively lacks convincing and supporting materials, and some arguments are not sufficiently rigorous. Based on the existing historical texts and the archaeological iconographic materials discovered since the 1980s, particularly the first-century Buddhist manuscripts recently found in Afghanistan, the commentator believes that the most plausible theory is that Buddhism reached China from the Greater Yuezhi of northwest India and took the land route to reach Han China. After entering China, Buddhism blended with early Daoism and Chinese traditional esoteric arts, and its iconography received blind worship.[5]

The French sinologist Henri Maspero says it is a "very curious fact" that, throughout the entire Han dynasty, Daoism and Buddhism were "constantly confused and appeared as single religion".[6] A century after prince Liu Ying's court supported both Daoists and Buddhists, in 166 Emperor Huan of Han made offerings to the Buddha and sacrifices to the Huang-Lao gods Yellow Emperor and Laozi.[7] The first Chinese apologist for Buddhism, a late second-century layman named Mouzi, said it was through Daoism that he was led to Buddhism—which he calls dàdào (大道, the "Great Dao").

I too, when I had not yet understood the Great Way (Buddhism), had studied Taoist practises. Hundreds and thousands of recipes are there for longevity through abstention from cereals. I practised them, but without success; I saw them put to use, but without result. That is why I abandoned them.[7]

Early Chinese Buddhism was conflated and mixed with Daoism, and it was within Daoist circles that it found its first adepts. Traces are evident in Han period Chinese translations of Buddhist scriptures, which hardly differentiated between Buddhist nirvana and Daoist immortality. Wuwei, the Daoist concept of non-interference, was the normal term for translating Sanskrit nirvana, which is transcribed as nièpán (涅槃) in modern Chinese usage.[8]

Traditional accounts

A number of popular accounts in historical Chinese literature have led to the popularity of certain legends regarding the introduction of Buddhism into China. According to the most popular one, Emperor Ming of Han (28–75 CE) precipitated the introduction of Buddhist teachings into China. The (early third to early fifth century) Mouzi Lihuolun first records this legend:

In olden days Emperor Ming saw in a dream a god whose body had the brilliance of the sun and who flew before his palace; and he rejoiced exceedingly at this. The next day he asked his officials: "What god is this?" the scholar Fu Yi said: "Your subject has heard it said that in India there is somebody who has attained the Dao and who is called Buddha; he flies in the air, his body had the brilliance of the sun; this must be that god."[9]

The emperor then sent an envoy to Tianzhu (Southern India) to inquire about the teachings of the Buddha.[10] Buddhist scriptures were said to have been returned to China on the backs of white horses, after which White Horse Temple was named. Two Indian monks also returned with them, named Dharmaratna and Kaśyapa Mātaṅga.

An eighth-century Chinese fresco at Mogao Caves near Dunhuang in Gansu portrays Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE) worshiping statues of a golden man; "golden men brought in 121 BCE by a great Han general in his campaigns against the nomads". However, neither the Shiji nor Book of Han histories of Emperor Wu mention a golden Buddhist statue (compare Emperor Ming).

The first translations

The first documented translation of Buddhist scriptures from various Indian languages into Chinese occurs in 148 CE with the arrival of the Parthian prince-turned-monk An Shigao (Ch. 安世高). He worked to establish Buddhist temples in Luoyang and organized the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese, testifying to the beginning of a wave of Central Asian Buddhist proselytism that was to last several centuries. An Shigao translated Buddhist texts on basic doctrines, meditation, and abhidharma. An Xuan (Ch. 安玄), a Parthian layman who worked alongside An Shigao, also translated an early Mahāyāna Buddhist text on the bodhisattva path.

Mahāyāna Buddhism was first widely propagated in China by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema (Ch. 支婁迦讖, active c. 164–186 CE), who came from the ancient Buddhist kingdom of Gandhāra. Lokakṣema translated important Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, as well as rare, early Mahāyāna sūtras on topics such as samādhi, and meditation on the buddha Akṣobhya. These translations from Lokakṣema continue to give insight into the early period of Mahāyāna Buddhism. This corpus of texts often includes emphasizes ascetic practices and forest dwelling, and absorption in states of meditative concentration:[11]

Paul Harrison has worked on some of the texts that are arguably the earliest versions we have of the Mahāyāna sūtras, those translated into Chinese in the last half of the second century CE by the Indo-Scythian translator Lokakṣema. Harrison points to the enthusiasm in the Lokakṣema sūtra corpus for the extra ascetic practices, for dwelling in the forest, and above all for states of meditative absorption (samādhi). Meditation and meditative states seem to have occupied a central place in early Mahāyāna, certainly because of their spiritual efficacy but also because they may have given access to fresh revelations and inspiration.

Early Buddhist schools

During the early period of Chinese Buddhism, the Indian early Buddhist schools recognized as important, and whose texts were studied, were the Dharmaguptakas, Mahīśāsakas, Kāśyapīyas, Sarvāstivādins, and the Mahāsāṃghikas.[13]

The Dharmaguptakas made more efforts than any other sect to spread Buddhism outside India, to areas such as Afghanistan, Central Asia, and China, and they had great success in doing so.[14] Therefore, most countries which adopted Buddhism from China, also adopted the Dharmaguptaka vinaya and ordination lineage for bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs. According to A.K. Warder, in some ways in those East Asian countries, the Dharmaguptaka sect can be considered to have survived to the present.[15] Warder further writes that the Dharmaguptakas can be credited with effectively establishing Chinese Buddhism during the early period:[16]

It was the Dharmaguptakas who were the first Buddhists to establish themselves in Central Asia. They appear to have carried out a vast circling movement along the trade routes from Aparānta north-west into Iran and at the same time into Oḍḍiyāna (the Suvastu valley, north of Gandhāra, which became one of their main centres). After establishing themselves as far west as Parthia they followed the "silk route", the east-west axis of Asia, eastwards across Central Asia and on into China, where they effectively established Buddhism in the second and third centuries A.D. The Mahīśāsakas and Kāśyapīyas appear to have followed them across Asia into China. ... For the earlier period of Chinese Buddhism it was the Dharmaguptakas who constituted the main and most influential school, and even later their Vinaya remained the basis of the discipline there.

Six Dynasties and Southern and Northern period (220–589)

Early translation methods

Initially, Buddhism in China faced a number of difficulties in becoming established. The concept of monasticism and the aversion to social affairs seemed to contradict the long-established norms and standards established in Chinese society. Some even declared that Buddhism was harmful to the authority of the state, that Buddhist monasteries contributed nothing to the economic prosperity of China, and that Buddhism was barbaric and undeserving of Chinese cultural traditions.[17] However, Buddhism was often associated with Taoism in its ascetic meditative tradition, and for this reason a concept-matching system was used by some early Indian translators, to adapt native Buddhist ideas onto Daoist ideas and terminology.[18][19]

Buddhism appealed to Chinese intellectuals and elites, and the development of gentry Buddhism was sought as an alternative to Confucianism and Daoism, since Buddhism's emphasis on morality and ritual appealed to Confucianists and the desire to cultivate inner wisdom appealed to Daoists. Gentry Buddhism was a medium of introduction for the beginning of Buddhism in China, it gained imperial and courtly support. By the early fifth century, Buddhism was established in south China.[20] During this time, Indian monks continued to travel along the Silk Road to teach Buddhism, and translation work was primarily done by foreign monks rather than Chinese.

The arrival of Kumārajīva (334–413 CE)

When the famous monk Kumārajīva was captured during the Chinese conquest of the Buddhist kingdom of Kucha, he was imprisoned for many years. When he was released in AD 401, he immediately took a high place in Chinese Buddhism and was appraised as a great master from the West. He was especially valued by Emperor Yao Xing of the state of Later Qin, who gave him an honorific title and treated him like a god. Kumārajīva revolutionized Chinese Buddhism with his high-quality translations (from AD 402–413), which are still praised for their flowing smoothness, clarity of meaning, subtlety, and literary skill. Due to the efforts of Kumārajīva, Buddhism in China became not only recognized for its practice methods, but also as high philosophy and religion. The arrival of Kumārajīva also set a standard for Chinese translations of Buddhist texts, effectively doing away with previous concept-matching systems.

The translations of Kumārajīva have often remained more popular than those of other translators. Among the most well-known are his translations of the Diamond Sutra, the Amitabha Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, the Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra, the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, and the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra.

A completed Sūtra Piṭaka

Around the time of Kumārajīva, the four major Sanskrit āgamas were also translated into Chinese. Each of the āgamas was translated independently by a different Indian monk. These āgamas comprise the only other complete surviving Sūtra Piṭaka, which is generally comparable to the Pali Sutta Pitaka of Theravada Buddhism. The teachings of the Sūtra Piṭaka are usually considered to be one of the earliest teachings on Buddhism and a core text of the Early Buddhist Schools in China. It is noteworthy that before the modern period, these āgama were seldom if ever used by Buddhist communities, due to their Hīnayāna attribution, as Chinese Buddhism was already avowedly Mahāyāna in persuasion.

Early Chinese Buddhist traditions

Due to the wide proliferation of Buddhist texts available in Chinese and the large number of foreign monks who came to teach Buddhism in China, much like new branches growing from the main tree trunk, various specific focus traditions emerged. Among the most influential of these was the practice of Pure Land Buddhism established by Hui Yuan, which focused on Amitābha Buddha and his western pure land of Sukhāvatī. Other early traditions were the Tiantai, Huayan and the Vinaya school.[21] Such schools were based upon the primacy of the Lotus Sūtra, the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, and the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, respectively, along with supplementary sūtras and commentaries. The Tiantai founder Zhiyi wrote several works that became important and widely read meditation manuals in China such as the "Concise samatha-vipasyana", and the "Great samatha-vipasyana".

Daily life of nuns

An important aspect of a nun was the practice of vegetarianism as it was heavily emphasized in the Buddhist religion to not harm any living creature for the purpose of them to consume. There were also some nuns who did not eat regularly, in an attempt to fast. Another dietary practice of nuns was their practice of consuming fragrant oil or incense as a "preparation for self-immolation by fire".[22]

Some daily activities of nuns include reading, memorizing, and reciting of Buddhist scriptures and religious texts. Another was meditation, as it is seen as the "heart of Buddhist monastic life". There are biographers explaining when nuns meditate they enter a state where their body of becomes hard, rigid, and stone-like where they are often mistaken as lifeless.[23]

Chan: pointing directly to the mind

In the fifth century, the Chan (Zen) teachings began in China, traditionally attributed to the Buddhist monk Bodhidharma, a legendary figure.[note 1] The school heavily utilized the principles found in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, a sūtra utilizing the teachings of Yogācāra and those of Tathāgatagarbha, and which teaches the One Vehicle (Skt. Ekayāna) to buddhahood. In the early years, the teachings of Chan were therefore referred to as the "One Vehicle School".[35] The earliest masters of the Chan school were called "Laṅkāvatāra Masters", for their mastery of practice according to the principles of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.

The principal teachings of Chan were later often known for the use of so-called encounter stories and koans, and the teaching methods used in them. Nan Huai-Chin identifies the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra and the Diamond Sūtra (Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra) as the principle texts of the Chan school, and summarizes the principles succinctly:

The Zen teaching was a separate transmission outside the scriptural teachings that did not posit any written texts as sacred. Zen pointed directly to the human mind to enable people to see their real nature and become buddhas.[36]

Sui and Tang dynasty (589–907 CE)

Xuanzang's journey to the west

During the early Tang dynasty, between 629 and 645, the monk Xuanzang journeyed to India and visited over one hundred kingdoms, and wrote extensive and detailed reports of his findings, which have subsequently become important for the study of India during this period. During his travels he visited holy sites, learned the lore of his faith, and studied with many famous Buddhist masters, especially at the famous center of Buddhist learning at Nālanda University. When he returned, he brought with him some 657 Sanskrit texts. Xuanzang also returned with relics, statues, and Buddhist paraphernalia loaded onto twenty-two horses.[37] With the emperor's support, he set up a large translation bureau in Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), drawing students and collaborators from all over East Asia. He is credited with the translation of some 1,330 fascicles of scriptures into Chinese. His strongest personal interest in Buddhism was in the field of Yogācāra, or "Consciousness-only".

The force of his own study, translation and commentary of the texts of these traditions initiated the development of the Faxiang school in East Asia. Although the school itself did not thrive for a long time, its theories regarding perception, consciousness, karma, rebirth, etc. found their way into the doctrines of other more successful schools. Xuanzang's closest and most eminent student was Kuiji who became recognized as the first patriarch of the Faxiang school. Xuanzang's logic, as described by Kuiji, was often misunderstood by scholars of Chinese Buddhism because they lack the necessary background in Indian logic.[38] Another important disciple was the Korean monk Woncheuk.

Xuanzang's translations were especially important for the transmission of Indian texts related to the Yogācāra school. He translated central Yogācāra texts such as the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra and the Yogācārabhūmi Śāstra, as well as important texts such as the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra and the Bhaiṣajyaguruvaidūryaprabharāja Sūtra (Medicine Buddha Sūtra). He is credited with writing or compiling the Cheng Weishi Lun (Vijñaptimātratāsiddhi Śāstra) as composed from multiple commentaries on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā-vijñaptimātratā. His translation of the Heart Sūtra became and remains the standard in all East Asian Buddhist sects. The proliferation of these texts expanded the Chinese Buddhist canon significantly with high-quality translations of some of the most important Indian Buddhist texts.

Caves, art, and technology

The popularization of Buddhism in this period is evident in the many scripture-filled caves and structures surviving from this period. The Mogao Caves near Dunhuang in Gansu province, the Longmen Grottoes near Luoyang in Henan and the Yungang Grottoes near Datong in Shanxi are the most renowned examples from the Northern Wei, Sui and Tang dynasties. The Leshan Giant Buddha, carved out of a hillside in the eighth century during the Tang dynasty and looking down on the confluence of three rivers, is still the largest stone Buddha statue in the world.

At the Longmen cave complex, Wu Zetian (r. 690–705) –– a notable proponent of Buddhism during the Tang dynasty (reigned as Zhou)–– directed mammoth stone sculptures of Vaircōcana Buddha with Bodhisattvas.[39][40] As the first self-seated woman emperor, these sculptures served multiple purposes, including the projection of Buddhist ideas that would validate her mandate of power.[39]

Monks and pious laymen spread Buddhist concepts through story-telling and preaching from sutra texts. These oral presentations were written down as bianwen (transformation stories) which influenced the writing of fiction by their new ways of telling stories combining prose and poetry. Popular legends in this style included Mulian Rescues His Mother, in which a monk descends into hell in a show of filial piety.

Making duplications of Buddhist texts was considered to bring meritorious karma. Printing from individually carved wooden blocks and from clay or metal movable type proved much more efficient than hand copying and eventually eclipsed it. The Diamond Sūtra (Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra) of 868 CE, a Buddhist scripture discovered in 1907 inside the Mogao Caves, is the first dated example of block printing.[41]

Ch'an Buddhism

After the arrival of Boddhidharma in the either 4th or 5th century in China, he founded the Chan Buddhism school becoming the first Patriarch (which is now known as Zen around the world due to the popularization of Japanese Zen ). The school of teaching became a major force during the Tang Dyansty with the Fifth Patriarch Hongren, his student Shenxiu who became the national teacher under the rule of Wu Zhetian, and the Sixth Patriach Huineng. Shenxiu and Huineng seemingly divided style created the Northern and Southern School of Chan. The Platform Sutra written by Huineng is the only Chinese produced Buddhist work that is given the status of a sutra normally only given to those expounded by the Buddha himself in India.

Arrival of Esoteric Buddhism

The Kaiyuan's Three Great Enlightened Masters, Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra, established Esoteric Buddhism in China from AD 716 to 720 during the reign of emperor Xuanzong. They came to Daxing Shansi (大興善寺, Great Propagating Goodness Temple), which was the predecessor of Temple of the Great Enlightener Mahavairocana. Daxing Shansi was established in the ancient capital Chang'an, today's Xi'an, and became one of the four great centers of scripture translation supported by the imperial court. They had translated many Buddhist scriptures, sutra and tantra, from Sanskrit to Chinese. They had also assimilated the prevailing teachings of China: Taoism and Confucianism, with Buddhism, and had further evolved the practice of the Chinese Esoteric Buddhist tradition.

They brought to the Chinese a mysterious, dynamic, and magical teaching, which included mantra formula and detailed rituals to protect a person or an empire, to affect a person's fate after death, and, particularly popular, to bring rain in times of drought. It is not surprising, then, that all three masters were well received by the emperor Tang Xuanzong, and their teachings were quickly taken up at the Tang court and among the elite. Mantrayana altars were installed in temples in the capital, and by the time of emperor Tang Daizong (r. 762–779) its influence among the upper classes outstripped that of Daoism. However, relations between Amoghavajra and Daizong were especially good. In life the emperor favored Amoghavajra with titles and gifts, and when the master died in 774, he honored his memory with a stupa, or funeral monument. Master Huiguo, a disciple of Amoghavajra, imparted some esoteric Buddhist teachings to Kūkai, one of the many Japanese monks who came to Tang China to study Buddhism, including the Mandala of the Two Realms, the Womb Realm and the Diamond Realm. Master Kukai went back to Japan to establish the Japanese Esoteric school of Buddhism, later known as Shingon Buddhism. The Esoteric Buddhist lineages transmitted to Japan under the auspices of the monks Kūkai and Saicho, later formulated the teachings transmitted to them to create the Shingon sect and the Tendai sect.

Unlike in Japan, Esoteric Buddhism in China was not seen as a separate and distinct "school" of Buddhism but rather understood as a set of associated practices and teachings that could be integrated together with the other Chinese Buddhist traditions such as Chan.[42] Hence, the other schools of Chinese Buddhism such as Chan and Tiantai began to adopt esoteric practices such as deity visualization and dharani chanting.[43][44][45]

Tang state repression of 845

Opposition to Buddhism accumulated over time during the Tang dynasty, culminating in the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution under Emperor Tang Wuzong.

There were several components that led to opposition of Buddhism. One factor is the foreign origins of Buddhism, unlike Taoism and Confucianism. Han Yu wrote, "Buddha was a man of the barbarians who did not speak the language of China and wore clothes of a different fashion. His sayings did not concern the ways of our ancient kings, nor did his manner of dress conform to their laws. He understood neither the duties that bind sovereign and subject, nor the affections of father and son."

Other components included the Buddhists' withdrawal from society, since the Chinese believed that Chinese people should be involved with family life. Wealth, tax-exemption status and power of the Buddhist temples and monasteries also annoyed many critics.[49]

As mentioned earlier, persecution came during the reign of Emperor Wuzong in the Tang dynasty. Wuzong was said to hate the sight of Buddhist monks, who he thought were tax-evaders. In 845, he ordered the destruction of 4,600 Buddhist monasteries and 40,000 temples. More than 400,000 Buddhist monks and nuns then became peasants liable to the Two Taxes (grain and cloth).[50] Wuzong cited that Buddhism was an alien religion, which is the reason he also persecuted the Christians in China. David Graeber argues that Buddhist institutions had accumulated so much precious metals which the government needed to secure the money supply.[51]

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960/979)

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period was an era of political upheaval in China, between the fall of the Tang dynasty and the founding of the Song dynasty. During this period, five dynasties quickly succeeded one another in the north, and more than 12 independent states were established, mainly in the south. However, only ten are traditionally listed, hence the era's name, "Ten Kingdoms". Some historians, such as Bo Yang, count eleven, including Yan and Qi, but not Northern Han, viewing it as simply a continuation of Later Han. This era also led to the founding of the Liao dynasty.

After the fall of the Tang dynasty, China was without effective central control during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. China was divided into several autonomous regions. Support for Buddhism was limited to a few areas. The Huayan and Tiantai schools survived, but they still suffered from the changing circumstances, since they had depended on imperial support. The collapse of Tang society also deprived the aristocratic classes of wealth and influence, which meant a further drawback for Buddhism. Shenxiu's Northern Chan School and Henshui's Southern Chan School didn't survive the changing circumstances. Nevertheless, Chan emerged as the most popular tradition within Chinese Buddhism, but with various schools developing various emphasises in their teachings, due to the regional orientation of the period. The Fayan school, named after Fayan Wenyi (885–958), became the dominant school in the southern kingdoms of Nan-Tang (Jiangxi, Chiang-hsi) and Wuyue (Che-chiang).[52]

Song dynasty (960–1279)

The Song dynasty is divided into two distinct periods: the Northern Song and Southern Song. During the Northern Song (北宋, 960–1127), the Song capital was in the northern city of Bianjing (now Kaifeng) and the dynasty controlled most of inner China. The Southern Song (南宋, 1127–1279) refers to the period after the Song lost control of northern China to the Jin dynasty. During this time, the Song court retreated south of the Yangtze River and established their capital at Lin'an (now Hangzhou). Although the Song dynasty had lost control of the traditional birthplace of Chinese civilization along the Yellow River, the Song economy was not in ruins, as the Southern Song Empire contained 60 percent of China's population and a majority of the most productive agricultural land.[53]

During the Song dynasty, Chan (禪) was used by the government to strengthen its control over the country, and Chan grew to become the largest sect in Chinese Buddhism. An ideal picture of the Chan of the Tang period was produced, which served the legacy of this newly acquired status.[54]

During the early Song dynasty, Chan and Pure Land practices became especially popular.[55] Buddhist ideology began to merge with Confucianism and Daoism, due in part to the use of existing Chinese philosophical terms in the translation of Buddhist scriptures. Various Confucian scholars of the Song dynasty, including Zhu Xi (wg: Chu Hsi), sought to redefine Confucianism as Neo-Confucianism.

During the Song dynasty, in 1021 CE, it is recorded that there were 458,855 Buddhist monks and nuns actively living in monasteries.[50] The total number of monks was 397,615, while the total number of nuns was recorded as 61,240.[50]

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

During the Yuan dynasty, the emperors made Esoteric Buddhism an official religion of their empire, and Tibetan lamas were given patronage at the court.[56] A common perception was that this patronage of lamas caused corrupt forms of tantra to become widespread.[56] When the Yuan dynasty was overthrown and the Ming dynasty was established, the Tibetan lamas were expelled from the court, and this form of Buddhism was denounced as not being an orthodox path.[56]

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

During the Ming dynasty, there was a significant revival of Tiantai, Huayan and Yogacara traditions, as well as ordination ceremonies.[57][58] While there were sometimes disagreements between certain lineage holders of the various Buddhist schools on doctrines, mixed practice of rituals and traditions from all the different schools remained the norm among monastics and lay people as opposed to strict sectarian divides.[59][42][60][61] According to Weinstein, by the Ming dynasty, the Chan school became especially popular such that, at one point, most monks were affiliated with either the Linji school or the Caodong school.[62]

Eminent monks

During the Ming dynasty, Hanshan Deqing was one of the great reformers of Chinese Buddhism.[63] Like many of his contemporaries, he advocated the dual practice of the Chan and Pure Land methods, and advocated the use of the nianfo ("Mindfulness of the Buddha") technique to purify the mind for the attainment of self-realization.[63] He also directed practitioners in the use of mantras as well as scripture reading. He was also renowned as a lecturer and commentator and admired for his strict adherence to the precepts.[63] According to Jiang Wu, for Chan masters in this period such as Hanshan Deqing, training through self-cultivation was encouraged, and clichéd or formulaic instructions were despised.[64] Eminent monks who practiced meditation and asceticism without proper Dharma transmission were acclaimed for having acquiring "wisdom without a teacher".[64]

Another eminent monastic in this era was the monk Youxi Chuandeng (1554–1628), who spearheaded the revival of the Tiantai teachings and lineage. While revitalizing Tiantai, he made an effort to harmonize rather than criticize other Buddhist schools. For instance, he incorporated the important intellectual themes of the late Ming, especially those found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra, with traditional Tiantai thought; by drawing upon the notions of pure mind and the seven elements found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra, he reinterpreted nature-inclusion and the Dharma-gate of inherent evil emphasizing inherent evil as pure rather than defiled.[58]

Eminent nuns

During the Ming dynasty, women of different ages were able to enter the monastic life from as young as five or six years old to as old as seventy.[65] There were various reasons why a Ming woman entered the religious life of becoming a nun. Some women had fallen ill and believed that by entering the religious life they would be able to relieve their sufferings.[66] Women who had been widowed due to the death of her husband or betrothed sometimes chose to join a convent.[67] Many women who were left widowed were affected financially as they often had to support their in-laws and parents. Remarriage was frowned upon in Ming society, where women were expected to remain faithful to their husband. By devoting themselves to religion, they received less social criticism. An example of this is Xia Shuji. Xia's husband, Hou Xun, (1591–1645), had led a resistance in Jiading which arrested the Qing troops who later on beheaded him.[68] Xia Shuji chose to seclude herself from outside life to devote herself to religion, and took on the religious name of Shengyin.[69]

During the late Ming, a period of social upheaval, the monastery or convent provided shelter for these women who no longer had protection from a male in their family (a husband, son, or father) due to death, financial constraint, and other situations.[65] However, in most circumstances, women who joined a nunnery did so because they wanted to escape a marriage, or they felt isolated as her husband has died. Such women also had to overcome many difficulties that arose socially from this decision. For most of these women, a convent was seen as a haven to escape their family or an unwanted marriage. Such difficulties were due to the social expectation of the women as it was considered unfilial to leave their duty as a wife, daughter, mother, or daughter in law.[70] There were also cases where individuals were sold by their family to earn money in a convent by reciting sutras and performing Buddhist services because they weren't able to financially support them.[71] Jixing entered a religious life as a young girl because her family had no money to raise her.[72]

Lastly, there were some who joined the Buddhist convent because of a spiritual calling where they found comfort in the religious life, such as Zhang Ruyu.[73] Zhang took the religious name Miaohui, and just before she entered the religious life she wrote the poem below:

Drinking at Rain and Flowers Terrace,

I Compose a Description the Falling Leaves

For viewing the vista, a 1000-chi terrace.

For discussing the mind, a goblet of wine.

A pure frost laces the tips of the trees,

Bronze leaves flirt with the river village.

Following the wave, I float with the oars;

Glory and decay, why sigh over them?

This day, I've happily returned to the source.[74]

Through her poetry, Miaohui (Zhang Ruyu) conveyed the emotions of fully understanding and concluding the difference in the life outside without devotion to religion and the life in a monastery, known as the Buddhist terms between "form and emptiness".[75] Women like Miaohui found happiness and fulfillment in the convent that they could not seek in the outside world. Despite the many reasons for entering the religious life, most women had to obtain permission from a male in their life (father, husband, or son).[76] Most nuns secluded themselves from the outside life away from their family and relatives.

Most nuns participated in religious practices with devotions to many different bodhisattva and Buddha. Some examples of bodhisattvas are Guanyin, Amitabha Buddha, Maitreya, and Pindola. One of the most prominent bodhisattvas in Chinese Buddhism is Guanyin, known as Goddess of Compassion, Mercy, and Love, and a protector and savior for those who worship and needs her aid.[77]

Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

The Qing court endorsed the Gelukpa School of Tibetan Buddhism.[78]

During the devastating Taiping rebellion (December 1850 – August 1864), the Taiping rebels targeted Buddhism destroying temples, and burning Buddhist images and scriptures.[79] In the Battle of Nanjing (1853), the Taiping army butchered thousands of monks in Nanjing. But from the middle of the Taiping rebellion, Taiping leaders took a more moderate approach, demanding that monks should have licences.

Around 1900, Buddhists from other Asian countries showed a growing interest in Chinese Buddhism. Anagarika Dharmapala visited Shanghai in 1893,[80] intending "to make a tour of China, to arouse the Chinese Buddhists to send missionaries to India to restore Buddhism there, and then to start a propaganda throughout the whole world", but eventually limiting his stay to Shanghai.[80] Japanese Buddhist missionaries were active in China in the beginning of the twentieth century.[80]

Republic of China (established 1912)

Pre-Communist Revolution

The modernisation of China led to the end of the Chinese Empire, and the installation of the Republic of China, which lasted on the mainland until the Communist Revolution and the installation of the People's Republic of China in 1949 which also led to the ROC government's exodus to Taiwan.

Under influence of the western culture, attempts were being made to revitalize Chinese Buddhism.[81] Most notable were the Humanistic Buddhism of Taixu and Yin Shun, and the revival of Chinese Chan by Hsu Yun.[81] Hsu Yun is generally regarded as one of the most influential Buddhist teachers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Other Buddhist traditions were similarly revitalized as well. In 1914, Huayan University, the first modern Buddhist monastic school, was founded in Shanghai to further systemize Huayan teachings to monastics and helped to expand the Huayan tradition. The university managed to foster a network of educated monks who focused on Huayan Buddhism during the twentieth century. Through this network, the lineage of the Huayan tradition was transmitted to many monks, which helped to preserve the lineage down to the modern day via new Huayan-centred organizations that these monks would later found.[82] For Tiantai Buddhism, the tradition's lineage (specifically the Lingfeng lineage) was carried from the late Qing into the twentieth century by the monk Dixian. His student, the monk Tanxu (1875–1963), is known for having rebuilt various temples during the Republican era (such as Zhanshan temple in Qingdao) and for preserving the Tiantai lineage into the PRC era. Other influential teachers in the early twentieth century included Pure land Buddhist master Shi Yinguang[83] and Vinaya master Hong Yi. Upasaka Zhao Puchu had worked very hard on the revival.

Until 1949, monasteries were built in the Southeast Asian countries, for example by monks of Guanghua Monastery, to spread Chinese Buddhism. Presently, Guanghua Monastery has seven branch monasteries in the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia.[84] Several Chinese Buddhist teachers left mainland China during the Communist Revolution, and settled in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Post-Communist Revolution

After the communist takeover of mainland China, many monastics followed the ROC's exodus to Taiwan. In the latter half of the twentieth century, many new Buddhist temples and organizations were set up by these monastics, which would later come to become influential back in mainland China after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

Four Heavenly Kings

Master Hsing Yun (1927–present) is the founder of Fo Guang Shan monastic order and the Buddha's Light International Association lay organization. Born in Jiangsu Province in mainland China, he entered the Sangha at the age of 12, and came to Taiwan in 1949. He founded Fo Guang Shan monastery in 1967, and the Buddha's Light International Association in 1992. These are among the largest monastic and lay Buddhist organizations in Taiwan from the late twentieth to early twenty-first centuries. He advocates Humanistic Buddhism, which the broad modern Chinese Buddhist progressive attitude towards the religion.

Master Sheng Yen (1930–2009) was the founder of the Dharma Drum Mountain, a Buddhist organization based in Taiwan which mainly advocates for Chan and Pure Land Buddhism. During his time in Taiwan, Sheng Yen was well known as one of the progressive Buddhist teachers who sought to teach Buddhism in a modern and Western-influenced world.

Master Cheng Yen (born 14 May 1937) is a Taiwanese Buddhist nun (bhikkhuni), teacher, and philanthropist.[85][86][87][88] She was a direct student of Master Ying Shun,[85] a major figure in the early development of Humanistic Buddhism in Taiwan. She founded the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation, ordinarily referred to as Tzu Chi in 1966. The organization later became one of the largest humanitarian organizations in the world, and the largest Buddhist organization in Taiwan.

Master Wei Chueh was born in 1928 in Sichuan, mainland China, and ordained in Taiwan. In 1982, he founded Lin Quan Temple in Taipei County and became known for his teaching on Chan practices by conducting many lectures and seven-day Chan meditation retreats, and eventually founded the Chung Tai Shan Buddhist order. The order has established more than 90 meditation centers and branches in Taiwan and abroad, including branches in Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Philippines, and Thailand.

Huayan

Several new Huayan-centred Buddhist organizations have been established since the latter half of the twentieth century. In contemporary times, the largest and oldest of the Huayan-centered organizations in Taiwan is the Huayan Lotus Society (Huayan Lianshe 華嚴蓮社), which was founded in 1952 by the monk Zhiguang and his disciple Nanting, who were both part of the network fostered by the Huayan University. Since its founding, the Huayan Lotus Society has been centered on the study and practice of the Huayan Sutra. It hosts a full recitation of the sutra twice each year, during the third and tenth months of the lunar calendar. Each year during the eleventh lunar month, the society also hosts a seven-day Huayan Buddha retreat (Huayan foqi 華嚴佛七), during which participants chant the names of the buddhas and bodhisattvas in the text. The society emphasizes the study of the Huayan Sutra by hosting regular lectures on it. In recent decades, these lectures have occurred on a weekly basis.[82] Like other Taiwanese Buddhist organization's, the Society has also diversified its propagation and educational activities over the years. It produces its own periodical and runs its own press. It also now runs a variety of educational programs, including a kindergarten, a vocational college, and short-term courses in Buddhism for college and primary-school students, and offers scholarships. One example is their founding of the Huayan Buddhist College (Huayan Zhuanzong Xueyuan 華嚴專宗學院) in 1975. They have also established branch temples overseas, most notably in California's San Francisco Bay Area. In 1989, they expanded their outreach to the United States of America by formally establishing the Huayan Lotus Society of the United States (Meiguo Huayan Lianshe 美國華嚴蓮社). Like the parent organization in Taiwan, this branch holds weekly lectures on the Huayan Sutra and several annual Huayan Dharma Assemblies where it is chanted. It also holds monthly memorial services for the society's spiritual forebears.[82]

Another Huayan-focused organization is the Huayan Studies Association Archived 30 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine (Huayan Xuehui 華嚴學會) which was founded in Taipei in 1996 by the monk Jimeng (繼夢), also known as Haiyun (海雲). This was followed in 1999 by the founding of the larger Caotangshan Great Huayan Temple (Caotangshan Da Huayansi 草堂山大華嚴寺). This temple hosts many Huayan-related activities, including a weekly Huayan Assembly. Since 2000, the association has grown internationally, with branches in Australia, Canada, and the United States.[82]

Tangmi

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism is also subject to a revitalization in both Taiwan and China, largely through connections and support from Kongōbu-ji, the head temple of the Kōyasan Shingon-shū (the school of Shingon Buddhism of Mount Kōya) and its affiliate temples.

The revival is mainly propagated by Chinese Buddhist monks who travel to Mount Kōya to be initiated and receive dharma transmission as acharyas in the Shingon tradition and who bring the esoteric teachings and practices back to Taiwan after their training has ended. While some of these Chinese acharyas have chosen to officially remain under the oversight of Kōyasan Shingon-shū and minister as Chinese branches of Japanese Shingon, many other acharyas have chosen to distinguish themselves from Shingon by establishing their own Chinese lineages after their return from Japan. Members from the latter group, while deriving their orthodoxy and legitimacy from Shingon, view themselves as re-establishing a distinctly Chinese tradition of Esoteric Buddhism rather than merely acting as emissaries of Japanese Shingon, in the same way that Kūkai started his own Japanese sect of Esoteric Buddhism after learning it from Chinese teachers.[89][90] One pertinent example is Master Wuguang (悟光上師), who was initiated as a Shingon acharya in Japan in 1971. He established the Mantra School Bright Lineage the following year in Taiwan, which recognizes itself as a resurrection of the Chinese Esoteric Buddhist transmission rather than a branch of Shingon.[89] Some Tangmi organizations in Taiwan that have resulted from the revival are:

- Mantra School Bright Lineage (真言宗光明流), which has branches in Taiwan and Hong Kong.[89][90]

- Zhenyan Samantabhadra Lineage (真言宗普賢流), which is mainly located in Taiwan.[89][90]

- Malaysian Mahā Praṇidhāna Parvata Mantrayāna (马来西亚佛教 真言宗大願山), an offshoot organization of the Mantra School Bright Lineage which is located in Malaysia.[89][90]

- Mahavairocana Temple (大毘盧寺), which has branches in Taiwan and America.

- Mount Qinglong Acala Monastery (青龍山不動寺), located in Taiwan.[89][90]

People's Republic of China (1949—present)

Chinese Buddhist Association

Unlike Catholicism and other branches of Christianity, there was no organization in China that embraced all monastics in China, nor even all monastics within the same sect. Traditionally each monastery was autonomous, with authority resting on each respective abbot. In 1953, the Chinese Buddhist Association was established at a meeting with 121 delegates in Beijing. The meeting also elected a chairman, 4 honorary chairmen, 7 vice-chairmen, a secretary general, 3 deputy secretaries-general, 18 members of a standing committee, and 93 directors. The 4 elected honorary chairmen were the Dalai Lama, the Panchen Lama, the Grand Lama of Inner Mongolia, and Venerable Master Hsu Yun.[91]

Persecution during the Cultural Revolution

Chinese Buddhism suffered extensive repression, persecution and destruction during the Cultural Revolution (from 1966 until Mao Zedong's death in 1976). Maoist propaganda depicted Buddhism as one of the four olds, as a superstitious instrument of the ruling class and as counter-revolutionary.[92] Buddhist Clergy were attacked, disrobed, arrested and sent to camps. Buddhist writings were burned. Buddhist temples, monasteries and art were systematically destroyed and Buddhist lay believers ceased any public displays of their religion.[92][93]

Reform and opening up – Second Buddhist Revival

Since the implementation of Boluan Fanzheng by Deng Xiaoping, a new revival of Chinese Buddhism began to take place in 1982.[94][95][96][97] Some of the ancient Buddhist temples that were damaged during the Cultural Revolution were allowed to be restored, mainly with the monetary support from oversea Chinese Buddhist groups. Monastic ordination were finally approved but with certain requirements from the government and new Buddhist temples are being built. Monastics who had been imprisoned or driven underground during the revolution were freed and allowed to return to their temples to propagate Buddhist teachings. For example, the monks Zhenchan (真禪) and Mengcan (夢參), who were trained in the Chan and Huayan traditions, travelled widely throughout China as well as other countries such as the United States and lectured on both Chan and Huayan teachings. Haiyun, the monk who founded the Huayan Studies Association in Taiwan, was a tonsured disciple of Mengcan.[82]

Monks who had fled the mainland to Taiwan, Hong Kong or other overseas Chinese communities after the establishment of the People's Republic of China also began to be welcomed back onto the mainland. Buddhist organizations which had been founded by these monks thus began to gain influence, revitalizing the various Buddhist traditions on the mainland. Recently, some Buddhist temples, administered by local governments, became commercialized by sales of tickets, incense, or other religious items; soliciting donations. In response, the State Administration for Religious Affairs announced a crackdown on religious profiteering in October 2012.[98] Many sites have done enough repairs and have already cancelled ticket fares and are receiving voluntary donation instead.[99][100]

In April 2006 China organized the World Buddhist Forum, an event now held every two years, and in March 2007 the government banned mining on Buddhist sacred mountains.[101] In May of the same year, in Changzhou, the world's tallest pagoda was built and opened.[102][103][104] Currently, there are about 1.3 billion Chinese living in the People's Republic. Surveys have found that around 18.2% to 20% of this population adheres to Buddhism.[105] Furthermore, PEW found that another 21% of the Chinese population followed Chinese folk religions that incorporated elements of Buddhism.[106]

Revival of Buddhist traditions

One example of the revitalization of Buddhist traditions on the mainland is the expansion of Tiantai Buddhism. The monk Dixian was a lineage holder in Tiantai Buddhism during the early twentieth century. During the Chinese Civil War, various dharma heirs of Dixian moved to Hong Kong, including Tanxu and Baojing. They helped establish the Tiantai tradition in Hong Kong, where it remains a strong living tradition today, being preserved by their dharma heirs.[107] After the reforms in mainland China, Baojing's dharma heir, Jueguang, helped to transmit the lineage back to mainland China, as well as other countries including Korea, Indonesia, Singapore and Taiwan.[108] The monk Yixing (益行), a dharma heir of Dixian who was the forty-seventh generation lineage holder of Tiantai Buddhism, was appointed as the acting abbot of Guoqing Temple and helped to restore Guanzong Temple, both of which remain major centres of Tiantai Buddhism in China.

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism was also revived on the mainland, similar to the situation in Taiwan. Organizations and temples propagating this tradition in China include Daxingshan Temple in Xi'an, Qinglong Temple in Xi'an, Yuanrong Buddhist Academy (圓融佛學院) in Hong Kong as well as Xiu Ming Society (修明堂), which is located primarily in Hong Kong, but also has branches in mainland China and Taiwan.[89][90]

Over the years, more and more Buddhist organizations have been approved to operate in the mainland. One example is the Taiwan-based organizations Tzu Chi Foundation and Fo Guang Shan, which were approved to open a branch in mainland China in March 2008.[109][110]

Chinese Buddhism in Southeast Asia

Chinese Buddhism is mainly practiced by Overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.

Chinese Buddhism in the West

The first Chinese master to teach Westerners in North America was Hsuan Hua, who taught Chan and other traditions of Chinese Buddhism in San Francisco during the early 1960s. He went on to found the City Of Ten Thousand Buddhas, a monastery and retreat center located on a 237-acre (959,000 m2) property near Ukiah, California. Chuang Yen Monastery and Hsi Lai Temple are also large centers.

Sheng Yen also founded dharma centers in the US.

With the rapid increase of immigrants from mainland China to Western countries in the 1980s, the landscape of the Chinese Buddhism in local societies has also changed over time. Based on fieldwork research conducted in France, some scholars categorize three patterns in the collective Buddhism practice among Chinese Buddhists in France: An ethnolinguistic immigrant group, a transnational organizational system, and information technology. These distinctions are made according to the linkages of globalization.

In the first pattern, religious globalization is a product of immigrants' transplantation of local cultural traditions. For example, people of similar immigration experiences establish a Buddha hall (佛堂) within the framework of their associations for collective religious activities.

The second pattern features the transnational expansion of a large institutionalized organization centered on a charismatic leader, such as Fo Guang Shan (佛光山), Tzu Chi (慈濟) and Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山).

In the third pattern, religious globalization features the use of information technology such as websites, blogs, Emails and social media to ensure direct interaction between members in different places and between members and their leader. The Buddhist organization led by Jun Hong Lu is a typical example of this kind of group.[111]

Notes

- ↑ Little contemporary biographical information on Bodhidharma is extant, and subsequent accounts became layered with legend.[24] There are three principal sources for Bodhidharma's biography:[25] Yáng Xuànzhī's (Yang Hsüan-chih) The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (547), Tánlín's preface to the Two Entrances and Four Acts (sixth century CE), which is also preserved in Ching-chüeh's Chronicle of the Lankavatar Masters (713–716),[26] and Dàoxuān's (Tao-hsuan) Further Biographies of Eminent Monks (seventh century CE). These sources, given in various translations, vary on their account of Bodhidharma being either:

- "[A] monk of the Western Region named Bodhidharma, a Persian Central Asian"[27] c.q. "from Persia"[28] (Buddhist monasteries, 547);

- "[A] South Indian of the Western Region. He was the third son of a great Indian king."[29] (Tanlin, sixth century CE);

- "[W]ho came from South India in the Western Regions, the third son of a great Brahman king"[30] c.q. "the third son of a Brahman king of South India" [28] (Lankavatara Masters, 713–716[26]/c. 715[28]);

- "[O]f South Indian Brahman stock"[31] c.q. "a Brahman monk from South India"[28] (Further Biographies, 645).

References

Citations

- ↑ Cook, Sarah (2017). The Battle for China's Spirit: Religious Revival, Repression, and Resistance under Xi Jinping. Freedom House Report. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ↑ Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ 中国文化科目认证指南. 华语教学出版社. Sinolingua. 2010. p. 64. ISBN 978-7-80200-985-1.

公元1世纪———传入中国内地,与汉文化交融,形成汉传佛教。

- ↑ Maspero 1981, pp. 401, 405.

- ↑ Rong Xinjiang, 2004, Land Route or Sea Route? Commentary on the Study of the Paths of Transmission and Areas in which Buddhism Was Disseminated during the Han Period, tr. by Xiuqin Zhou, Sino-Platonic Papers 144, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Maspero 1981, p. 405.

- 1 2 Maspero 1981, p. 406.

- ↑ Maspero 1981, p. 409

- ↑ Tr. by Henri Maspero, 1981, Taoism and Chinese Religion, tr. by Frank A. Kierman Jr., University of Massachusetts Press, p. 402.

- ↑ Hill (2009), p. 31.

- ↑ Williams, Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. 2008. p. 30

- ↑ Label for item no. 1992.165.21 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 281

- ↑ Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 278

- ↑ Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 489

- ↑ Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. pp. 280–281

- ↑ Bentley, Jerry. Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times 1993. p. 82

- ↑ Oh, Kang-nam (2000). The Taoist Influence on Hua-yen Buddhism: A Case of the Sinicization of Buddhism in China. Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal, No. 13, (2000). Source: (accessed: 28 January 2008) p.286 Archived 23 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Further discussion of can be found in T'ang, Yung-t'ung, "On 'Ko-I'", in Inge et al. (eds.): Radhakrishnan: Comparative Studies in Philosophy Presented in Honour of His Sixtieth Birthday (London: Allen and Unwin, 1951) pp. 276–286 (cited in K. Ch'en, pp. 68 f.)

- ↑ Jerry Bentley Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 78.

- ↑ 法鼓山聖嚴法師數位典藏. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ Kathryn Ann Tsai, Lives Of The Nuns. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), pp. 10.

- ↑ Kathryn Ann Tsai, Lives Of The Nuns., pp. 11.

- ↑ McRae 2003.

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005, p. 85–90.

- 1 2 Dumoulin 2005, p. 88.

- ↑ Broughton 1999, p. 54–55.

- 1 2 3 4 McRae 2003, p. 26.

- ↑ Broughton 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005, p. 89.

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005, p. 87.

- ↑ Kambe n.d.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1987, p. 125–126.

- ↑ "Masato Tojo, Zen Buddhism and Persian Culture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ↑ The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, translated with notes by Philip B. Yampolsky, 1967, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-08361-0, page 29, note 87

- ↑ Basic Buddhism: exploring Buddhism and Zen, Nan Huai-Chin, 1997, Samuel Weiser, page 92.

- ↑ Jerry Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 81.

- ↑ See Eli Franco, "Xuanzang's proof of idealism". Horin 11 (2004): 199–212.

- 1 2 Sullivan, Michael (2008). The Arts of China. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-520-25569-2.

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia (2003). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- ↑ "Diamond Sutra". Landmarks in Printing. The British Library. Archived from the original on 6 March 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- 1 2 Esoteric Buddhism and the tantras in East Asia. Charles D. Orzech, Henrik Hjort Sorensen, Richard Karl Payne. Leiden: Brill. 2011. ISBN 978-90-04-20401-0. OCLC 731667667.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ D., Orzech, Charles (2011). Esoteric buddhism and the tantras in East Asia. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18491-6. OCLC 716806704.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Sharf, Robert (30 November 2005). Coming to Terms with Chinese Buddhism A Reading of the Treasure Store Treatise. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6194-0. OCLC 1199729266.

- ↑ Bernard., Faure (1997). The will to orthodoxy : a critical genealogy of Northern Chan Buddhism. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2865-8. OCLC 36423511.

- ↑ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan Archived 15 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19 Archived 15 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ↑ Ethnic Sogdians have been identified as the Caucasian figures seen in the same cave temple (No. 9). See the following source: Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin", in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134–163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ↑ For information on the Sogdians, an Eastern Iranian people, and their inhabitation of Turfan as an ethnic minority community during the phases of Tang Chinese (seventh–eighth century) and Uyghur rule (ninth–thirteenth century), see Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ↑ Palumbo, Antonello (2017). "Exemption Not Granted: The Confrontation between Buddhism and the Chinese State in Late Antiquity and the 'First Great Divergence' Between China and Western Eurasia". Medieval Worlds. medieval worlds (Volume 6. 2017): 118–155. doi:10.1553/medievalworlds_no6_2017s118. ISSN 2412-3196.

- 1 2 3 Gernet, Jacques. Verellen, Franciscus. Buddhism in Chinese Society. 1998. pp. 318–319

- ↑ Graeber, David (2011). Debt: The First 5000 Years. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House. pp. 265–6. ISBN 978-1-933633-86-2.

- ↑ Welter 2000, p. 86–87.

- ↑ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais 2006, p. 167.

- ↑ McRae 2003, p. 119–120.

- ↑ Heng-Ching Shih (1987). Yung-Ming's Syncretism of Pure Land and Chan, The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 10 (1), p. 117

- 1 2 3 Nan Huai-Chin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. York Beach: Samuel Weiser. 1997. p. 99.

- ↑ Wu, Jiang (1 April 2008). Enlightenment in Dispute. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195333572.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-533357-2.

- 1 2 Ma, Yung-fen (2011). The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng (1554-1628) (Thesis). Columbia University. doi:10.7916/d81g0t8p.

- ↑ Orzech, Charles D. (November 1989). "Seeing Chen-Yen Buddhism: Traditional Scholarship and the Vajrayāna in China". History of Religions. 29 (2): 87–114. doi:10.1086/463182. ISSN 0018-2710. S2CID 162235701.

- ↑ Sharf, Robert H. (2002). Coming to terms with Chinese Buddhism : a reading of the treasure store treatise. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-585-47161-4. OCLC 53119548.

- ↑ Faure, Bernard (1997). The will to orthodoxy : a critical genealogy of Northern Chan Buddhism. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2865-8. OCLC 36423511.

- ↑ Stanley Weinstein, "The Schools of Chinese Buddhism", in Kitagawa & Cummings (eds.), Buddhism and Asian History (New York: Macmillan 1987) pp. 257–265, 264.

- 1 2 3 Keown, Damien. A Dictionary of Buddhism. 2003. p. 104

- 1 2 Jiang Wu. Enlightenment in Dispute. 2008. p. 41

- 1 2 Kathryn Ann Tsai, Lives Of The Nuns. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), pp. 6.

- ↑ Yunu Chen, "Buddhism and the Medical Treatment of Women in the Ming Dynasty". Na Nu (2008):, pp. 290.

- ↑ Beata Grant (2008). "Setting the Stage: Seventeenth-Century Texts and Contexts". In Eminent Nuns: Women Chan Masters of Seventeenth-Century China (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.), pp. 4 JSTOR j.ctt6wqcxh.6

- ↑ Beata Grant, "Setting the Stage: Seventeenth-Century Texts and Contexts". In Eminent Nuns: Women Chan Masters of Seventeenth-Century China pp., 5.

- ↑ Beata Grant, "Setting the Stage: Seventeenth-Century Texts and Contexts". In Eminent Nuns: Women Chan Masters of Seventeenth-Century China., pp. 6.

- ↑ Beata Grant., and Wilt Idema, "Empresses, Nuns, and Actresses. In The Red Brush: Writing Women of Imperial China. (Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center), pp. 157. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1tg5kw2.

- ↑ Yunu Chen, "Buddhism and the Medical Treatment of Women in the Ming Dynasty". Na Nu (2008):, pp. 295.

- ↑ Beata Grant, Daughters of Emptiness Poems of Chinese Buddhist Nuns. (Boston: Wisdom Publication), pp. 56.

- ↑ Karma Lekshe Tsomo, Buddhist Women Across Cultures. (New York: State University of New York Press), pp. 98.

- ↑ Karma Lekshe Tsomo, Buddhist Women Across Cultures., pp. 99.

- ↑ Karma Lekshe Tsomo, Buddhist Women Across Cultures. (New York: State University of New York Press), pp. 100.

- ↑ Kathryn Ann Tsai, Lives Of The Nuns. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), pp. 7.

- ↑ Wilt Idema. Personal Salvation And Filial Piety: Two Precious Scroll Narratives of Guanyin and her Acolytes. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), pp. 6.

- ↑ Mullin 2001, p. 358

- ↑ Chün-fang Yü. Chinese Buddhism: A Thematic History, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 240. 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Buddhism and Buddhists in China – IX. Present-Day Buddhism (by Lewis Hodus)". www.authorama.com.

- 1 2 Huai-Chin, Nan (1999), Basic Buddhism. Exploring Buddhism and Zen, Mumbai: Jaico Publishing House

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hammerstrom, Erik J. (2020). The Huayan University Network: The Teaching and Practice of Avataṃsaka Buddhism in Twentieth-Century China. New York. ISBN 978-0-231-55075-8. OCLC 1154101063.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "重現一代高僧的盛德言教". Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ "Voice of Longquan, Guanghua Monastery". Archived from the original on 18 December 2012.

- 1 2 Foundation, Tzu Chi. "Biography of Dharma Master Cheng Yen". www.tzuchi.org.tw. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ↑ "Tricycle » Diane Wolkstein on Dharma Master Cheng Yen". 6 September 2010. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ↑ "Founder of Tzu Chi Receives Rotary International Hono". religion.vn. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ↑ "Cheng Yen – The 2011 Time 100 Poll". Time. 4 April 2011. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bahir, Cody (1 January 2018). "Replanting the Bodhi Tree: Buddhist Sectarianism and Zhenyan Revivalism". Pacific World. Third Series. 20: 95–129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bahir, Cody (31 December 2013). "Buddhist Master Wuguang's (1918–2000) Taiwanese Web of the Colonial, Exilic and Han". The e-Journal of East and Central Asian Religions. 1: 81–93. doi:10.2218/ejecar.2013.1.737. ISSN 2053-1079.

- ↑ Holmes, Welch (1961). "Buddhism Under the Communists", China Quarterly, No.6, Apr–June 1961, pp. 1–14.

- 1 2 Yu, Dan Smyer. "Delayed contention with the Chinese Marxist scapegoat complex: re-membering Tibetan Buddhism in the PRC". The Tibet Journal, 32.1 (2007)

- ↑ "murdoch edu". Archived from the original on 25 December 2005.

- ↑ Laliberte 2011.

- ↑ Lai 2003.

- ↑ "RELIGION-CHINA: Buddhism Enjoys A Revival". Inter Press Service. 30 November 2010.

- ↑ "Erica B. Mitchell (201), A Revival of Buddhism?". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ↑ "Commercialization of temples in China prompts ban on stock listings, crackdown on profiteering". Washington Post. Beijing. Associated Press. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ "湖南29家寺院取消门票免费开放-中新网". www.chinanews.com.cn.

- ↑ "净慧法师呼吁全国佛教名山大寺一律免费开放_佛教频道_凤凰网". fo.ifeng.com.

- ↑ "China bans mining on sacred Buddhist mountains". Reuters. 23 August 2007.

- ↑ "China temple opens tallest pagoda". BBC News. 1 May 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ "Photo in the News: Tallest Pagoda Opens in China". Archived from the original on 4 May 2007.

- ↑ "archive.ph". archive.ph. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Buddhists | Pew Research Center". 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Siqi, Yang (16 March 2016). "Life in Purgatory: Buddhism Is Growing in China, But Remains in Legal Limbo". Time.

- ↑ Ji Zhe, Gareth Fisher, André Laliberté (2020). Buddhism after Mao: Negotiations, Continuities, and Reinventions, pp. 136–138. University of Hawaii Press.

- ↑ Ji Zhe, Gareth Fisher, André Laliberté (2020). Buddhism after Mao: Negotiations, Continuities, and Reinventions, pp. 139–140. University of Hawaii Press.

- ↑ "Tzu Chi Foundation Approved To Open Branch In Mainland China – ChinaCSR.com – Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) News and Information for China". Archived from the original on 5 July 2008.

- ↑ 中國評論新聞網.

- ↑ Ji, Zhe (14 January 2014). "Buddhist Groups among Chinese Immigrants in France: Three Patterns of Religious Globalization". Review of Religion and Chinese Society. 1 (2): 212–235. doi:10.1163/22143955-04102006b. ISSN 2214-3947.

Sources

- Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999), The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-21972-4

- Chen, Kenneth Kuan Sheng. Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1964.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History, vol. 1: India and China, Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1

- Han Yu. Sources of Chinese Tradition. c. 800.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (paperback), Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66991-7

- Ebrey, Patricia; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 978-0-618-13384-0

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. John E. Hill. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hodus, Lewis (1923), Buddhism and Buddhists in China

- Kambe, Tstuomu (n.d.), Bodhidharma. A collection of stories from Chinese literature (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2015, retrieved 19 February 2013

- Lai, Hongyi Harry (2003), The Religious Revival in China. In: Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies 18

- Laliberte, Andre (2011), Buddhist Revival under State Watch, in: Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 40, 2,107–134

- Liebenthal, Walter. Chao Lun – The Treatises of Seng-Chao Hong Kong, China, Hong Kong University Press, 1968.

- Liebenthal, Walter. Was ist chinesischer Buddhismus Asiatische Studien: Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft, 1952 Was ist chinesischer Buddhismus

- McRae, John R. (2000), "The Antecedents of Encounter Dialogue in Chinese Ch'an Buddhism", in Heine, Steven; Wright, Dale S. (eds.), The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, Oxford University Press

- McRae, John (2003), Seeing Through Zen, The University Press Group Ltd.

- Mullin, Glenn H. The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnations (2001) Clear Light Publishers. ISBN 1-57416-092-3.

- Saunders, Kenneth J. (1923). "Buddhism in China: A Historical Sketch", The Journal of Religion, Vol. 3.2, pp. 157–169; Vol. 3.3, pp. 256–275.

- Welch, Holmes. The Practice of Chinese Buddhism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Welch, Holmes. The Buddhist Revival in China. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1968.

- Welch, Holmes. Buddhism under Mao. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1972.

- Welter, Albert (2000), Mahakasyapa's smile. Silent Transmission and the Kung-an (Koan) Tradition. In: Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright (eds.)(2000): "The Koan. Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press

- Yang, Fenggang; Wei, Dedong, THE BAILIN BUDDHIST TEMPLE: THRIVING UNDER COMMUNISM (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2010

- Zhu, Caifang (2003), Buddhism in China Today: The Example of the Bai Lin Chan Monastery. Perspectives, Volume 4, No.2, June 2003 (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2010

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1987), "The Sound of the One Hand", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 107 (1): 125–126, doi:10.2307/602960, JSTOR 602960