| History of Corsica |

|---|

|

|

|

.svg.png.webp)

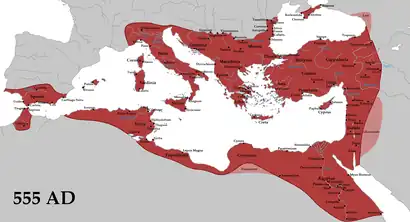

The history of Corsica goes back to antiquity, and was known to Herodotus, who described Phoenician habitation in the 6th century BCE. Etruscans and Carthaginians expelled the Phoenicians, and remained until the Romans arrived during the Punic Wars in 237 BCE. Vandals occupied it in 430 CE, followed by the Byzantine Empire a century later.

Raided by various Germanic and other groups for two centuries, it was conquered in 774 by Charlemagne under the Holy Roman Empire, which fought for control against the Saracens. After a period of feudal anarchy, the island was transferred to the papacy, then to city states Pisa and Genoa, which retained control over it for five centuries, until the establishment of the Corsican Republic in 1755. The French gained control in the 1768 Treaty of Versailles. Corsica was briefly independent as a Kingdom in union with Great Britain after the French Revolution in 1789, with a viceroy and elected Parliament, but returned to French rule in 1796.

Corsica strongly supported the allies in World War I, caring for wounded, and housing POWs. The poilus fought loyally and suffered great casualties. A recession after the war prompted a mass exodus to southern France. Wealthy Corsicans became colonizers in Algeria and Indochina.

After the Fall of France in 1940, Corsica was part of the southern zone libre of the Vichy regime. Fascist leader Benito Mussolini agitated for Italian control, supported by Corsican irredentists. In 1942, Italy occupied Corsica with a huge force. German forces took over in 1943 after the Allied armistice with Italy. The Germans faced opposition from the French Resistance, retreating and evacuating the island by October 1943. Corsica then became an Allied air base, supporting the Mediterranean Theater in 1944, and the invasion of southern France in August 1944. Since the war, Corsica has developed a thriving tourism industry, and has been known for its independence movements, sometimes violent.

Prehistory

The prehistory of Corsica covers the long period from the Upper Paleolithic to the first historical event, the founding of Aléria by the ancient Greeks in 566 BCE.

Geography

The history of Corsica has been influenced by its strategic position at the heart of the western Mediterranean and its maritime routes, only 12 kilometres (7 mi) from Sardinia, 50 kilometres (30 mi) from the Isle of Elba, 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the coast of Tuscany and 200 kilometres (120 mi) from the French port of Nice. At 8,778 square kilometres (3,389 sq mi), Corsica is the fourth largest island in the Mediterranean, after Sicily, Sardinia and Cyprus.

Classical antiquity

Name

The ancient Greeks, notably Herodotus, called the island Kurnos or Kyrnos (from kur or kyr meaning cape);[2] the name Corsica is Latin and was in use in the Roman Republic.[3]

Why Herodotus used Kyrnos and not some other name remains a mystery, and the phrases of the authors give no clue. The Roman historians, however, believed Corsa or Corsica (rightly or wrongly they interpreted -ica as an adjectival formative ending) was the native name of the island, but they could not give an explanation of its meaning. They did think that the natives were originally Ligures.[4]

Phoenician and Greek footholds

According to Herodotus, the Phoenicians became the first to colonize the island. Ionian Greeks established a brief foothold in Corsica with the foundation of Aléria in 566 BCE. They were expelled by an alliance of the Etruscans and the Carthaginians following the Battle of Alalia (c. 540-535 BCE). The Etruscans, then Carthage, dominated the island until the Roman Republic annexed it in 237 BCE during the period of the Punic Wars.

Roman era

The island was under Etruscan and Carthaginian influence until 237 BCE, when it was taken over by the Roman Republic. The Etruscans were confined to a few coastal settlements, such as Aléria, and the Carthaginians were strong on neighboring Sardinia. The Romans, however, had a profound influence, colonizing the entire coast, permeating inland and changing the unknown indigenous language to Latin. Corsica remained under Roman rule until its conquest by the Vandals in 430 CE. It was recovered by the Byzantine Empire in 534, adding a late-ancient Greek influence.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Corsica was frequented by migrant peoples and corsairs, notably Vandals, who plundered and ravaged at will until the coastal settlements fell into decline and the population occupied the slopes of the mountains. Rampant malaria in the coastal marshes reinforced this decision. Due largely to competition for the island from Ostrogothic Foederati who had settled on the Riviera, the Vandals never penetrated much beyond the coast, and their stay in Corsica was relatively short-lived, just long enough to prejudice the Corsicans against foreign adventurers on Corsican soil.

In 534, the armies of Justinian I recovered the island for the empire, but the Byzantines were not able to effectively defend the island from continuing raids by the Ostrogoths, the Lombards, and the Saracens. The Lombards, who had made themselves masters of the war- and famine-shattered Italian Peninsula, conquered the island in c. 725.

The Lombard supremacy on the island was short lived. In 774, the Frankish king Charlemagne conquered Corsica as he moved to subdue the Lombards and restore the Western Empire. For the next century and a half, the thus established Holy Roman Empire continually warred with the Saracens for control of the island. In 807, Charlemagne's constable Burchard defeated an invading force from Al Andalus.[5] In c. 930, Berengar II, King of Italy, invaded and subdued the imperial forces. Otto I vanquished Berengar and restored Corsica to imperial control in 965.

Its external threats mostly vanquished, a period of feudal anarchy followed as local Corsican-based nobles warred on each other and struggled for control, culminating in the transfer of the island – at the request of its population – to the papacy in 1077. The Pope yielded civic administration to Pisa in 1090, but contention between the Pisans and their rival Genoese soon engulfed Corsica. Repeated truces proved fleeting as the two naval and trading powers clashed for supremacy in the Western Mediterranean. The various Italian republics that arose began to assume responsibility for the security and prosperity of Corsica, starting with Tuscany, the closest. Corsica was finally removed from the fighting by annexation to the Papal States in 1217.

Renaissance

Pisa retained control of the island during most of the Middle Ages but at the start of the Renaissance it fell to Genoa in 1284, following the battle of Meloria against Pisa.

Corsica successively was part of the Republic of Genoa for five centuries. Despite take-overs by Aragon between 1296–1434 and France between 1553 and 1559, Corsica would remain under Genoese control until the Corsican Republic of 1755 and under partial control until its purchase by France in 1768.

Bank of Saint George

However, the dissension and political conflict at home did not always permit Doges of Genoa to govern Corsica well or at all. During such periods the island was subject to destructive conflict between coalitions of signorial families. The Bank of Saint George became involved as a major creditor of the Republic of Genoa. As security for their public loans they had obtained a franchise to collect public money; i.e., taxes.

In 1453 the people of Corsica held a general assembly, or Diet, at Lago Benedetto at which they voted to request the protection of the Bank of Saint George as a credible third-party. In return the bank would get the right to exercise their franchise in Corsica. This third-party solution became immediately popular. The government of Genoa placed Corsica in the bank's hands and the major contenders on Corsica agreed to a peace, some accepting cash payments for their cooperation.[6]

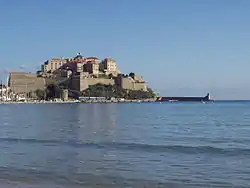

Throughout the next century the bank undertook enterprises in the major coastal cities, sending in troops to secure the strong points, building or rebuilding the citadels, recruiting several hundred colonists per city, mainly Genoese, and constructing quarters for them within a city wall. Most of these "old cities" survive and are populated today, having served as the nucleus of modern Corsican coastal cities.

The natives were at first kept at bay. Typically more or less immediately but certainly by a few generations they were allowed to conurbate with the Genoese, especially as the latter were decimated by malaria and required the assistance of the natives. Some conflict continued but within a few decades peace and order were restored to the island. Genoese watchtowers populated the entire coastline (and are there yet) where the forces of Genoese signori ruling from coastal castles kept a watchful eye for raiders, pirates, bandits and smugglers.

Sampiero Corso

.jpg.webp)

Having begun its dominion in Corsica by building walled cities from which the Corsicans were to be excluded, the Bank of Saint George in the exercise of its taxation franchise finally became as unpopular in some quarters as the Republic of Genoa. It too generated a population of Corsican exiles, one of whom, Sampiero Corso, immigrated to France and became ultimately a high-ranking officer in the French army. He was thus on hand in Italy during the Italian War of 1551–1559 when the question came up in a conference of the general staff of what to do with Corsica, which was between France and Italy. At the insistence of Corso and other well-placed exiles the Marshal Paul de Termes gave orders, without the knowledge or assent of his commander, Henry II of France, to take Corsica.[7]

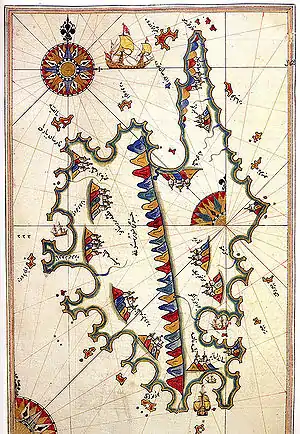

In August 1553, the Turkish fleet under Dragut, an ally of the French under a Franco-Ottoman alliance, set sail transporting French troops to Cap Corse in the Invasion of Corsica (1553). Bastia fell on the 24th, Saint-Florent on the 26th, Corte shortly after and Bonifacio in September. Before they could take Calvi the Turks went home in October for unknown reasons. Sampiero Corso proceeded to raise civil war in central Corsica, pitting signor against signor, wasting the villages of his opponents.

That November, Henry II opened negotiations with Genoa but too late. While parlaying the Genoese sent their best commander, Admiral Andrea Doria, with 15,000 men to Cap Corse, recapturing Saint-Florent in February 1554. By 1555, the French had been cleared from most of the coastal cities and Doria left. A Turkish fleet sent to help was decimated by the plague and went home towing empty ships, assisted by Genoese gold. Sampiero fought on in the hinterland.

Peace was finally brokered by Elizabeth I of England. By the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559, the French returned Corsica to Genoa. Left without support, Corso went again into exile. Peace was restored, but not before the Genoese had dealt severely with the traitorous Signori.

Enlightenment

Corsican society had always been relatively egalitarian, and writer Dorothy Carrington claims, "Alone among the peoples of Europe the Corsicans avoided feudal and capitalist oppression."[8]

The Age of Enlightenment overthrew signorial and colonial rule and brought some measure of self-rule to the island. As the Corsican constitution was drawn up in 1755, Corsica is distinguished by having staged the first enlightenment revolution, being upstaged only by the English Revolution of the preceding century. It was the first of a trio: Corsican, American, French, and as such had some influence on the American Revolution. Corsica never did obtain total sovereignty but it shared in the French Revolution, became part of France, and acquired the local autonomy and civil rights established by that revolution.

Genoese rule in the 18th century was less than satisfactory to Corsicans, who considered it corrupt and ineffective. The Genoese on their part used their citadels and watch towers in an attempt to control a population that without its assent could not be controlled. The Corsicans had a bastion of their own, the mountains, but steadily the number of exiles abroad grew and those began to look for ways and means to free Corsica from all foreign powers. At no point in the Corsican history had the island ever been a nation of its own, nor did it ever achieve that goal. In the 18th century, however, Corsicans were able to establish a partial republic in which the Genoese were penned up in the citadels but ruled nowhere else. The republic began with a search by the exiles for a savior, a man of great ability who could step in and lead them to victory and self-rule.

Revolution of 1729–36

In 1729, a full-scale revolt broke out in Corsica. In April 1731, having been unable to contain the outbreak, the Genoese appealed to the Emperor Charles VI, as feudal suzerain of the island, for military assistance.[9] The moment was propitious, since the emperor was on good terms with the Duke of Savoy and the King of Spain, and had just signed agreement with the Maritime Powers. In July, 4,000 men of the garrison of Milan were sent to Corsica at the expense of Genoa. The Genoese desired to keep the expedition small and the cost low, but the military expert Eugene of Savoy convinced the emperor to increase the number of troops to 12,000 by 1732. The war degenerated into a guerrilla campaign in the mountains, which the professional forces of the emperor could not win.[9]

After negotiations were opened, the Corsicans offered their island's sovereignty to Charles or, if he refused, Eugene. A final agreement was signed at Corte on 13 May 1732, whereby the Genoese would return to power and implement reforms. An amnesty was granted to all rebels and the emperor guaranteed the accord.[9] The emperor was unable to prevent Genoa returning to its former mismanagement, and island rose up again in 1734.[9]

In the second phase of the revolt, the Corsican leader, Giacinto Paoli, requested Spanish assistance. None arrived before the German adventurer Theodor von Neuhoff, who convinced the people to elect him King Theodore of Corsica in March 1736.[10] He left in October 1736 to seek support abroad, and was arrested in Amsterdam and thrown in debtors' prison.[9]

Corsican Republic

A capable advocate of Corsican independence at last stepped forward from the ranks of Corsicans in exile in Italy, Pasquale Paoli, a general and patriot who struggled against Genoa and then France, and became Il Babbu di a Patria (Father of the Nation). In 1755 he proclaimed the Corsican Republic. Paoli founded the first University of Corsica (with instruction in Italian). He chose the Moor's head ("Testa Mora"), previously used by Theodore of Corsica, as Corsica's emblem in 1760. Paoli considered the Corsicans to be an Italian people.

Sale and annexation to France

Seeing that attempts to dislodge Paoli were futile, in 1764 by secret treaty Genoa sold Corsica to the Duke of Choiseul, then minister of the French Navy, who bought it on behalf of the crown. On the quiet, French troops gradually replaced Genoese in the citadels. In 1768, after preparations had been made, an open treaty with Genoa ceded Corsica to France in perpetuity with no possibility of retraction and the Duke appointed a Corsican supporter, Buttafuoco, as administrator. The island rose in revolt. Paoli fought a guerrilla war against fresh French troops under their commander, Comte de Marbeuf, but was defeated in the Battle of Ponte Novu and had to go into exile in Vienna and then London. The French move into Corsica triggered the Corsican Crisis in Britain, where debate raged over the question of British intervention. In 1770, Marbeuf publicly announced the annexation of Corsica and appointed a governor.

Anglo-Corsican Kingdom

After the French revolution, Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli, who had been exiled under the monarchy, became something of an idol of liberty and democracy. In 1789 he was invited to Paris by the National Constituent Assembly and was celebrated as a hero in front of the assembly. He was afterwards sent back to Corsica having been given the rank of lieutenant-general.

In 1795, after proclaiming the independence of Corsica, a constitution was adopted that made Corsica a kingdom in personal union with Great Britain, represented by a viceroy. The constitution was considered quite democratic for its time, with an elected Parliament and a Council. Sir Gilbert Elliot served as viceroy whereas Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo served as head of government (effectively a prime minister). The island returned to French rule in 1796.

French First Empire

Modern era

19th century

From 1854 to 1857 the Société du Télégraphe Électrique or "The Mediterranean Electric Telegraph", a company started by John Watkins Brett, connected La Spezia, Italy with Corsica by submarine cable, being the first to do so. The line ran south along the east coast, partly on land, partly on sea, from Cap Corse to Ajaccio, where a second cable crossed the Strait of Bonifacio. Brett's intended links across Sardinia and through the deeps to Bona, Algeria, failed because of decimation of the crews by malaria and the technical difficulties of laying cable in deep waters. By 1870 Paris could communicate with Algeria by telegraph through Corsica.[11]

First World War and after

In World War I Corsica responded to the call to arms more intensely than any other allied region. Out of a population estimated by a diplomat of the times to have been about 300,000, some 50,000 Corsican men were under arms: a ratio greater than one of every six Corsican citizens.[12]

The civilian population was correspondingly pro-allied. Prisoners of war were sent to Corsica. There they occupied every available space from rooms in monasteries to cells in citadels. Stone sheds were converted for their use. When all else failed, wooden barracks were constructed on the mountainsides. The prisoners were put to work in agriculture and forestry. Corsica was also turned into a hospital for the wounded. Most of the allies sent medical units or volunteers. The island was so useful as a base that the sea lanes leading to it were under constant surveillance and attack by U-boats.[13]

Corsican poilus fought loyally and with valor. Estimates of casualties vary but most are over 50%. As a result, the survivors became established in the upper echelons of the French military and police.[14] However, the loss of manpower contributed to a recession and mass exodus from Corsica in favor of southern France in the post-war period. Corsicans of means became colonizers during this period, the descendants of the former signori starting agricultural enterprises in Vietnam, Algeria and Puerto Rico.[14] It was on them that the blow of subsequent wars of independence fell most heavily.

Second World War

After the Allied defeat of 1940, Corsica became part of the Southern zone of Vichy France, and was thus not directly occupied by Axis forces, but fell under ultimate military control of Nazi Germany. A campaign of rhetoric by Benito Mussolini asserting that Corsica belonged to Italy was reinforced by the irredentist movement of Italian-speaking Corsicans (such as Petru Giovacchini) who advocated the unification of the island with Italy.

In November 1942, as part of its invasion of the southern zone, Germany arranged for fascist Italy to occupy Corsica as well as some parts of France up to the Rhône river. The Italian occupation force in Corsica grew to over 85,000 troops, later reinforced by 12,000 German troops – a huge occupation force relative to the size of the local population of 220,000.[15] The French had no troops with which to prevent the occupation. Irredentist propaganda intensified, but the préfet representing the French government restated French sovereignty over the island and stated that the Italian troops were occupiers.[16]

The French Resistance soon began developing under the impetus of loyal local inhabitants (the Maquis named after the 18th-century partisans of Pasquale Paoli),[17] and of Free French leaders starting in December 1942, with Charles de Gaulle eventually sending Paulin Colonna d'Istria from Algeria to unite the movements. Boosted via six visits by the Free French submarine Casabianca, and further armed by Allied airdrops, the strengthened Resistance was met with fierce repression by the OVRA (Italian fascist police) and the fascist Black Shirts paramilitary groups but gained strength, especially in the countryside.[18][19]

In July 1943, following the Fall of the Fascist regime in Italy, 12,000 German troops came to Corsica. They formally took over the occupation on 9 September 1943, the day after the Armistice of Cassibile. Following the Allied landings in Sicily and the Italian surrender, these German troops were joined by the remnants of the Africa Division of the German army, reconstituted as the 90th Panzergrenadier Division with about 40,000 men,[20] which crossed over from Sardinia. They were accompanied by some Italian Social Republic forces. They faced Resistance forces which had been asked to occupy the mountains to prevent Axis troop movements between the Corsican coasts, as well as a subset of Royal Italian Army troops that allied with them but whose contribution was hampered as their leadership was ambivalent.[21] The German forces retreated from Bonifacio towards the Northern harbor of Bastia. Elements of the reconstituted French I Corps, from the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, landed in Ajaccio to counter the German movement and the Germans evacuated Bastia by 4 October 1943, leaving behind 700 dead and 350 POWs.

After Corsica was thus liberated from the forces of the Third Reich, the island started functioning as an Allied air base in support of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations in 1944; in particular, groups of the 57th Bomb Wing were stationed along the east coast from Bastia in the north to Solenzara in the south. Corsica was also one of the bases from which Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France in August 1944, was launched.

While on the island, U.S. Army engineers successfully eradicated the malaria that had been endemic to the coastal areas of Corsica,[22] including half the island's arable land that had been previously uninhabitable.[23]

Modern era

In recent decades, Corsica has developed a thriving tourism industry, which has attracted a sizeable number of immigrants to the island in search of employment. Various movements, calling for either greater autonomy or complete independence from France, have been launched, some of whom have at times used violent means, like the National Front for the Liberation of Corsica (FLNC). In May 2001, the French government granted the island of Corsica limited autonomy, launching a process of devolution in an attempt to end the push for nationalism.

Corsica served as the start of the 2013 Tour de France, the first time that the event was staged on the island.[24]

References

- ↑ Antonetti, Pierre. "The Moor's Head ... A Symbol". Trois Etudes sur Paoli. corseweb. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- ↑ Lavezzi, Ghjiseppu (2018). Corse : Vertiges de l'honneur: L'Âme des Peuples (in French). Nevicata. p. 10. ISBN 978-2-512-01011-1. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ Knight, Charles (1853). The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge. p. 994. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ Smith, William (1872). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: J. Murray. pp. 689–692. Downloadable Google Books.

- ↑ Annali d'Italia: Dall'anno 601 dell'era volare fino all'anno 840, by Lodovico Antonio Muratori, Giuseppe Catalani, Monaco (1742); page 466.

- ↑ Gregorovius, Ferdinand Adolf (1855). Wanderings in Corsica; its history and its heroes. Translated by Muir, A. Oxford University Press. p. 31.

- ↑ Braudel, Fernand (1996). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Translated by Reynolds, Sian. University of California Press. pp. 926–933. ISBN 0-520-20330-5.

- ↑ Carrington, Dorothy (1974). Corsica: portrait of a granite island. New York: John Day Co. p. 11. ISBN 0-381-98260-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Peter Hamish Wilson, German Armies: War and German Society, 1648–1806 (Routledge 1998), 208.

- ↑ For his career, see Julia Gasper, Theodore von Neuhoff, King of Corsica: The Man Behind the Legend (University of Delaware Press, 2013). Gasper considers the entire period of intermittent revolt between 1729 and the French annexation of 1768 to be a forty-year "Corsican War of Independence".

- ↑ Glover, Bill (2008). "History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications from the first submarine cable of 1850 to the worldwide fiber optic network". FTL Design. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ↑ Meriwether, Lee (1919). The War Diary of a Diplomat. Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 56.

- ↑ Meriwether page 17.

- 1 2 Bikales, Gerda (Winter 2003–2004). "Corsican Capers – Island Separatists Highlight France's Malaise". 14 (2). Retrieved 20 July 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Dillon, Paddy (2006). Gr20 – Corsica: The High-level Route. Cicerone Press Limited. p. 14. ISBN 1-85284-477-9.

- ↑ Davide Rodogno (2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-521-84515-1.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C.; Priscilla Mary Roberts; Jack Greene (2004). World War II: A Student Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 808. ISBN 1-85109-857-7.

- ↑ Hélène Chaubin, Sylvain Gregory, Antoine Poletti (2003). La résistance en Corse (CD-ROM). Paris: Association pour des Études sur la Résistance Intérieure.

- ↑ Général Gambiez. Liberation de la Corse. Hachette, Paris 1973, p. 128.

- ↑ Hoyt, Edwin Palmer (2006). Backwater War: The Allied Campaign in Italy, 1943–45. Stackpole Books. p. 74. ISBN 0-8117-3382-3.

- ↑ Lamb, Richard (1996). War in Italy: A Brutal Story. New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 178–181. ISBN 0-306-80688-6.

- ↑ Toty, Céline; Barré, Hélène; Le Goff, Gilbert; Larget-Thiéry, Isabelle; Rahola, Nil; Couret, Daniel; Fontenille, Didier (12 August 2010). "Malaria risk in Corsica, former hot spot of malaria in France". Malaria Journal. 9 (1): 231. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-9-231. ISSN 1475-2875. PMC 2927611. PMID 20704707.

- ↑ "World: The Corsican Curse". Time. 29 October 1965. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ↑ "Grand Départ 2013 - Corsica - Tour de France 2013". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Aldrich. Robert. "France's Colonial Island: Corsica and the Empire" French History & Civilization (2009), Vol. 3, p112-125.

- "Corsica", Italy (2nd ed.), Coblenz: Karl Baedeker, 1870, OL 24140254M

- Candea, Matei. Corsican fragments: difference, knowledge, and fieldwork (Indiana UP, 2010).

- Carrington, Dorothy. Granite Island: A Portrait of Corsica (London, 1971).

- Gregory, Desmond. Ungovernable Rock: A History of the Anglo-Corsican Kingdom & Its Role in Britain's Mediterranean Strategy during the Revolutionary War (1793-1797) (1986) 211pp.

- Hall, Thadd E. "Thought and practice of enlightened government in French Corsica." American Historical Review 74.3 (1969): 880–905. online

- McLaren, Moray. "Pasquale Paoli: Hero of Corsica." History Today (Nov 1965) 15#11 pp 756–761.

- Meeks, Joshua. "Revolutionary Corsica, 1789–1793." in France, Britain, and the Struggle for the Revolutionary Western Mediterranean (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2017) pp. 41–73.

- Nicholas, Nick. "A history of the Greek colony of corsica." Journal of the Greek Diaspora 31 (2005): 33–78. covers 1600 to 1799. online

- Playfair, R. Lambert (1892), "Corsica", Handbook to the Mediterranean (3rd ed.), London: J. Murray, OL 16538259M

- Savigear, Peter. "Intervention and the Balance of Power: An Eighteenth Century War of Liberation" Studies in History & Politics (1981) 2#2 pp 113–126, on Pasquale Paoli in 1768

- Varley, Karine. "Between Vichy France and fascist Italy: Redefining identity and the enemy in Corsica during the Second World War." Journal of Contemporary History 47.3 (2012): 505-527 online.

- Willis, F. Roy. "Development planning in eighteenth-century France: Corsica's Plan Terrier." French Historical Studies 11.3 (1980): 328–351. online

- Wilson, Stephen. Feuding, Conflict and Banditry in Nineteenth-Century Corsica (1988). 565pp.

French works

- Antonetti, Pierre (1973). Histoire de la Corse. Paris: R. Laffont..

- Costa, Laurent-Jacques (2004). Corse préhistorique: peuplement d'une île et modes de vie des sociétés insulaires, IXe-IIe millénaires av. J.-C. Paris: Errance. ISBN 2-87772-273-2..

- Costa, Laurent-Jacques (2006). Questions d'économie préhistorique. Modes de vie et échange en corse et en Sardaigne. Ajaccio: Éditions du CRDP..

- De Cursay, Marc (2008). Corse : la fin des mythes. Paris: Éditions Lharmattan..

- Mérimée, Prosper. Colomba: histoire d'une jeune corse qui pousse son frère à venger la mort de son père..

- Renucci, Janine (2001). La Corse. Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-037169-8..

- Vergé-Franceschi, Michel (1996). Histoire de la Corse. Paris: Éditions du Félin. ISBN 2-86645-221-6. 2 volumes..

External links

- "Map of Corsica". UNRV.com. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

French links

- deCursay, Marc (ed.). "Histoires Corse ne nous racontons pas d'Histoires". les Plumes du Paon. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- "LA LIBÉRATION DE LA CORSE. 9 septembre – 4 octobre 1943". La Préfecture et les services de l'État en Corse. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

English links

- Negroni, Héctor Andrés (April 1996). "Historical Summary of the Negroni Family". Boletin de la Sociedad Puertorriqueña de Genealogía. 8 (1–2). Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- Ptolemy, Claudius. Thayer, William (ed.). "Corsica Island: Sixth Map of Europe". The Geography. Retrieved 30 April 2008..