History of Czech civilian firearms possession extends over 600 years back when the Czech lands became the center of firearms development, both as regards their technical aspects as well as tactical use.

In 1419, the Hussite revolt against Catholic church and Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor started. The ensuing Hussite wars over religious freedom and political independence represented a clash between professional Crusader armies from all around Europe, relying mostly on standard medieval tactics and cold weapons, and primarily commoners' militia-based Czech forces which relied on use of firearms. First serving as auxiliary weapons, firearms gradually became indispensable for the Czech militia.

The year 1421 marks a symbolical beginning of the Czech civilian firearms possession due to two developments: enactment of formal duty of all inhabitants to obey call to arms by provisional Government in order to defend the country and first battle in which Hussite Taborite militia employed firearms as the main weapons of attack.[4]

A universal right to keep arms was affirmed in the 1517 Wenceslaus Agreement. In 1524 the Enactment on Firearms was passed, establishing rules and permits for carrying of firearms. Firearms legislation remained permissive until the 1939-1945 German occupation. The 1948-1989 period of Communist dictatorship marked another period of severe gun restrictions.[5]

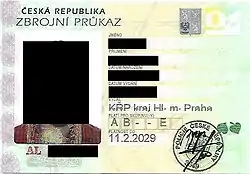

Permissive legislation returned in the 1990s. Citizens’ ability to be armed has been considered an important aspect of liberty. Today, the vast majority of Czech gun owners possess their firearms for protection, with hunting and sport shooting being less common.[6] 250,342 out of 307,372 legal gun owners possess licenses for the reason of protection of life, health and property (31 Dec 2020), which allows them to carry concealed firearms anywhere in the country.[7]

The "right to acquire, keep and bear firearms" is explicitly recognized in the first Article of the Firearms Act. On a constitutional level, the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms includes the "right to defend one’s own life or the life of another person also with arms".

Historical development

Origins of civilian firearms possession

Late 14th and early 15th century saw gradually increasing use of firearms in siege operations both by defenders and attackers. Weight, lack of accuracy and cumbersome use of early types limited their employment to static operations and prevented wider use in open battlefield or by civilian individuals. Nevertheless, lack of guild monopolies and low training requirements lead to their relatively low price. This together with high effectiveness against armour led to their popularity for castle and town defenses.[4]

When the Hussite revolt started in 1419, the Hussite militias heavily depended on converted farm equipment and weapons looted from castle and town armories, including early firearms. Hussite militia consisted mostly of commoners without prior military experience and included both men and women. Use of crossbows and firearms became crucial as those weapons didn't require extensive training, nor did their effectiveness rely on operator's physical strength.[4]

Firearms were first used in the field as provisional last resort together with wagon fort. Significantly outnumbered Hussite militia led by Jan Žižka repulsed surprise assaults by heavy cavalry during Battle of Nekmíř in December 1419 and Battle of Sudoměř in March 1420. In these battles, Žižka employed transport carriages as wagon fort to stop enemy's cavalry charge. Main weight of fighting rested on militiamen armed with cold weapons, however firearms shooting from behind the safety of the wagon fort proved to be very effective. Following this experience, Žižka ordered mass manufacturing of war wagons according to a universal template as well as manufacturing of new types of firearms that would be more suitable for use in the open battlefield.[4]

Throughout 1420 and most of 1421 the Hussite tactical use of wagonfort and firearms was defensive. The wagons wall was stationary and firearms were used to break initial charge of the enemy. After this, firearms played auxiliary role supporting mainly cold weapons based defense at the level of the wagon wall. Counterattacks were done by cold weapons armed infantry and cavalry charges outside of the wagon fort.[4]

The first dynamic use of war wagons and firearms took place during Hussite breakthrough of Catholic encirclement at Vladař Hill in November 1421 Žlutice Battle. The wagons and firearms were used on move, at this point still only defensively. Žižka avoided main camp of the enemy and employed the moving wagon fort in order to cover his retreating troops.[4]

Firearms becoming primary weapons

The first true engagement where firearms played primary role happened a month later during the Battle of Kutná Hora. Žižka positioned his severely outnumbered forces between the town of Kutná Hora that pledged allegiance to the Hussite cause and the main camp of the enemy, leaving supplies in the well defended town. However, as the Crusaders conducted unsuccessful cavalry charge against the Hussite forces on 21 December, uprising of ethnic minority German townsmen led the town into Catholic control. This left Hussite wagon fort squeezed between the fortified town and the main enemy camp consisted of the best professional warriors from 30 countries that the Crusader force could assemble.[4][8][9]

In late night between 21 and 22 December 1421, Žižka ordered break out charge directly through the enemy's main camp. Czech Hussite militia conducted the attack against the multinational professional army by gradually moving wagon wall. Instead of usual infantry raids beyond the wagons, the attack relied mainly on use of ranged weapons from the moving war wagons. Nighttime use of firearms proved extremely effective not only practically but also psychologically.[4]

1421 marked not only change in importance of firearms from auxiliary to primary weapons of Hussite militia, but also establishment by Čáslav diet of formal legal duty of all inhabitants to obey call to arms of elected provisional Government. For the first time in medieval European history, this was not put in place in order to fulfill duties to a feudal lord or to the church, but in order to participate in defense of the country.[9]

Firearms design underwent fast development during the hussite wars and their civilian possession became a matter of course throughout the war as well as after its end in 1434.[5] The word used for one type of hand held firearm used by the Hussites, Czech: píšťala, later found its way through German and French into English as the term pistol.[10] Name of a cannon used by the Hussites, the Czech: houfnice, gave rise to the English term, "howitzer" (houf meaning crowd for its intended use of shooting stone and iron shots against massed enemy forces).[11][12][13] Other types of firearms commonly used by the Hussites included hákovnice, an infantry weapon heavier than píšťala, and yet heavier tarasnice (fauconneau). As regards artillery, apart from houfnice Hussites employed bombarda (mortar) and dělo (cannon).

16th century legislation and statutory recognition of right to be armed

The right to keep arms was formally recognized through the 1517 St. Wenceslaus Agreement. The agreement was signed between the Czech nobility and burghers after lengthy disputes over the extent of each other's privileges, as both began to fear possible widespread farmer and commoners uprising. While most of the agreement dealt with different issues, it stated that "all people of all standing have the right to keep firearms at home" for purpose of protection in case of war. At the same time, it set a universal ban on carrying of firearms. This, in effect, made conventions of armed farmers and commoners illegal while preserving semblance of legal equality as the ban affected also the nobles and burghers.[5]

General ban on carrying was lifted mere several years later. In 1524 a comprehensive "Enactment on Firearms" (zřízení o ručnicích) was adopted. This lengthy act also focused on ban on carrying of firearms and set details for its enforcement and penalties. While almost entirely setting details of the carry ban, in its closing paragraph the act set a process of issuing carry permits. As permits could be granted either by nobility or by town officials, this put nobles and burghers in clear advantage over the farmer and commoner gun owners.[5]

The 1524 Enactment on Firearms also explicitly stated the right of the nobles and burghers to keep firearms at home for personal protection. While not stating such right explicitly for the rest of the inhabitants, the fact that the enactment sets details of universal carry ban (unless a person has a firearm carry permit) with details of enforcement and penalties aimed at nobles, burgers and rest of the people respectively, makes it clear that they continued to have the right to keep firearms at their homes in line with the 1517 St. Wenceslaus Agreement.[5]

18th and 19th century firearm laws

Gun control laws enacted during the early 18th century dealt with illegal use of firearms for poaching. At the time, hunting was an exclusive noble privilege with little to no legal option for participation of common folk. Despite tough sentences of 12 years of hard labor or death introduced by a 1727 enactment, poaching with use of firearms remained widespread to the point that a 1732 Royal Gamekeeping Rules noted that gamekeepers were in constant danger of being shot by poachers.[14]

A 1754 enactment introduced up to one-year imprisonment for carrying of daggers and pocket pistols ("tercerols") as well as tough sentencing for cases of attacking or resisting law enforcement with use of these weapons. Mere brandishing of a weapon against a state official was to be punished by life imprisonment. Wounding a state official would be punished by decapitation, killing of state official by cutting of hand followed by decapitation. Another 1754 enactment limited possibility of shooting within limits of certain cities to licensed shooting ranges, showing early development of sport shooting in the country.[14]

A 1789 decree on hunting also included firearms related measures. Any person merely passing through someone's hunting grounds was obliged to either strip trigger off or wrap their firearm in cloth under penalty of confiscation as well as complete ban on firearms possession.[14] Other enactments limited use of firearms in cities "close to buildings" and on state roads (especially shooting to air during religious celebrations), citing fire hazard as a main concern. In general, however, people were free to possess and carry firearms as they wished, with another 1797 enactment specifying that loaded firearms at home must be kept in a way preventing their use by children.[14]

Gun control enactments adopted in the following three decades focused on banning of insidious weapons such as daggers or rifles hidden in walking sticks. Despite having been already banned under the 1727 law, foreword to 1820 enactment lamented their widespread presence among population both within cities as well as in the countryside.[14]

Imperial Regulation No. 223

Following power reconciliation after failed 1848 revolution, emperor Franz Joseph I enacted the Imperial Regulation No. 223 in 1852. According to the regulation, citizens had the right to possess firearms in a number "needed for personal use"; possession of unusually high number of firearms required a special permit. Pistols shorter than 18 centimeters (entire length) were banned altogether as well as rifles disguised as walking sticks. Firearms and ammunition manufacturing was subject to licence acquisition.[14]

The law also introduced firearm carry permits. A carry permit was available to person with clean criminal record subject to paying a fee. It needed to be renewed after three years. Certain civilians did not need a permit: hunters, shooting range members, those wearing traditional clothing that had firearm as customary accessory. During emergency state, carrying of firearms could have been provisionally prohibited.[14]

Another regulation of 1857 explicitly banned private ownership of artillery, while 1898 regulation lifted the ban on small pistols (shorter than 18 cm).[14]

Independent Czechoslovakia

After the establishment of independent Czechoslovakia in 1918, the country kept the gun law of 1852 (see above), i.e. the citizens had the right to possess firearms and needed to obtain a permit in order to be able to carry them.[15] Possession and carrying of concealed pistols became a commonplace in the country.

After Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany in 1933, local ethnic German party established its own armed "security force." In 1938, Hitler brought his demand for succession of part of Czechoslovak borderland that was inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans. The party's security force was transformed into a paramilitary organization called "Sudetendeutsches Freikorps" which started conducting terror operations against Czechoslovak state, Jews and ethnic Czechs. Especially snipers using scoped hunting rifles became particular concern. This led to adoption of Act No. 81/1938, on Firearms and Ammunition, which for the first time introduced licensing system not only for carrying of firearms, but also for firearms possession. Ministry of Interior was supposed to enact a regulation that would set rules for obtaining the licenses, however, this never happened. Freikorps was receiving illegal shipments of firearms from Germany, making the envisioned licensing scheme useless. Thus, despite the new law, the rules of 1852 still remained in force.

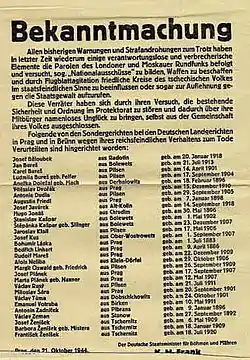

Nazi gun ban

Germany, Poland and Hungary seized Czech borderland following the Munich agreement with UK, France and Italy, in October 1938, immediately putting into force their own restrictive gun laws within the occupied territory.

On 15 March 1939, Germany invaded the remainder of the Czech Lands. On the very first day, Chief Commander of German forces ordered surrender of all firearms present within the occupied territory. This pertained not only to civilian-owned firearms, but also to those held by the police force. In August 1939, this order was replaced by Regulation of Reich Protector No. 20/39. The regulation again ordered the surrender of all firearms and introduced personal responsibility of land plot owners for all firearms that would be found within their property. Reich and Protectorate officials (including police) and SS Members were exempt from the gun ban. Licensed hunters could own up to 5 hunting guns and up to 50 pieces of ammunition. Long rimfire rifles, sport pistols up to 6 mm calibre, air rifles and museum guns were allowed, however they needed to be registered. Simple failure to surrender a firearm carried up to 5 years imprisonment, while hiding of cache of firearms carried the death penalty. Offenders were tried in front of German courts.[15]

Another Regulation of October 1939 ordered surrender of all books on firearms and explosives, as well as all air rifles "that look like military rifles", which was obviously aimed at vz.35 training air rifle that had appearance of vz.24 Czechoslovak main battle rifle.[15]

From May 1940 onwards, illegal possession of a firearm was punishable by death.[15]

Communist gun ban

The 1852 Imperial Regulation became again effective following the defeat of Germany in May 1945 and remained in force until 1950.[15]

In 1948, Communists conducted a successful coup in Czechoslovakia and started drafting a number of laws that would secure their grip on power, including the Firearms Act No. 162/1949 that became effective in February 1950. The new law introduced licensing for both possession and carrying. License to possess could be obtained from the District National (communist) Committee in case that "there is no concern of possible misuse". The same applied for license to carry, for which there was also a specific reason needed. Since 1961, the authority to issue license was given to local police chiefs, subject to the same requirements. Given that state apparatus constantly feared counterrevolution, only those deemed loyal to the party had any chance of getting a license.[15]

Ministry of Interior issued in June 1962 a secret guidance no. 34/1962 which specified conditions under which the police chiefs may have issued a license in accordance with the 1949 enactment. License to possess and carry short firearms may have been issued to named categories of persons (members of government, deputies, party functionaries, communist people's militia members, procurators, judges, etc.). Permit to possess and carry a long hunting rifle may have been issued only to "certified and reliable persons devoted to the socialist system". Referencing the secret guidance while issuing or denying the license was strictly forbidden.[15]

A new Firearms Act was adopted in 1983 as No. 147/1983. License remained may issue subject to consideration whether "public interest" doesn't prevent firearms possession by the given person. Apart from other formalities, the applicant needed to present also a declaration from their employer. Licenses were now available for sport shooting purposes, whereby the applicant needed to present recommendation of a local sport shooting society (which was run by the party). For the first time, the applicant also needed to be cleared by his general practitioner. Licenses were issued for a period of 3 years subject to renewal. Similarly as before, the enactment was accompanied by secret guidance of the Ministry of Interior No. 5/1984. The guidance again limited access to firearms to selected classes, mainly Communist Party members. Newly, sport shooters that achieved required performance bracket could also obtain license. Possession of hunting shotguns was less restrictive.[15]

Modern era

1990–1995

Following the Velvet Revolution, an amendment act No. 49/1990 Coll. was adopted. Under the new law, any person older than 18, with clean criminal record, physically and mentally sound that did not pose threat of misuse of the firearm could have license issued. License may have been issued for purpose of hunting, sport shooting, exercise of profession and in special cases also for protection (concealed carry). Newly, denial of license could be challenged in court.[15]

Even though the law remained may issue, practice of issuing licenses became permissive due to abolishment of communist secret police directive that previously included detailed gun restriction rules.

1995–2002

A general overhaul of firearms legislation took place through act No. 288/1995 Coll.

The new legislation completely left the may issue system previously introduced during communist rule. Gun licenses became shall issue, including for purposes of concealed carry for protection.[15]

Since 2002

Accession to EU required a new law compliant with the European Firearms Directive, which was passed in 2002. New law, which is effective to this day, on one hand introduced more EU mandated bureaucracy into the process of issuing of licenses and purchasing firearms, but at the same time streamlined some previous restrictions (e.g. newly not only pistols and revolvers could be possessed for purpose of self-defense, but any type of firearm).[15]

Recent developments

Minor changes to the 2002 Firearms Act

The 2002 Firearms Act was amended multiple times, however most of the changes were minor. The main basics of the law were unchanged.

- 2004 – inclusion of pyrotechnical survey under the act (new type F license)

- 2005 – change of definition of historical firearms (i.e. D Cat not requiring license) from "developed or manufactured prior to 1890" to "manufactured prior to 1890" (i.e. functional replica possession requires license)

- 2008

- inclusion of citizens of European Economic Area and Switzerland under the same set rules pertaining to citizens of EU countries

- tighter sanctions for use of firearms (concealed carry, hunting, shooting at ranges) while intoxicated (loss of license)

- 2009 – exemption for A category firearms may now be given only A type license holder (e.g. exemptions for fully automatic firearms would newly be given only for firearms collection purposes, not for self-defense), A category firearms may not be conceal carried any more,

- 2014

- new licenses issued for 10 years instead of 5

- in case that police has a well founded suspicion that the gun owner's state of health has changed so as to lead to loss of his health clearance, they may ask him to present a new health clearance, failure to do so within 30 days may lead to revocation of license

- new possibility of license owner to surrender the license, if he wishes to do so

- possibility of B and C type license holders to obtain exemption for A category accessories (e.g. night vision scope for hunters)

- E type license holder allowed to reload ammunition for their own purposes (before, only B and C type license holders)

- 2016

- in case that police have a well founded suspicion that the gun owner's state of health has changed so as to lead to loss of his health clearance so that he may present danger to self or others, they may provisionally seize his firearms and ammo; in case that the given person fails to comply, police may also enter his home without judicial warrant to do so; however, firearms must be returned to the owner immediately after reasons for seizure expire (e.g. owner presents new health clearance) – adopted in reaction to Uherský Brod shooting

- police allowed to enter home and other premises without judicial warrant in case that other reason for seizure of firearms exists and the owner has failed to surrender them (e.g. indictment for intentional felony)

- police use new registry of misdemeanors for determination of personal reliability – adopted in reaction to Uherský Brod shooting

- 2017 (effective since August 2017, delayed part of 2016 amendment)

- laser sights are not A category accessory any more

- government loses authority to order surrender of firearms during state of emergency or war

- F type license no longer issued, transferred to armament license

2014 European parliamentary elections

Generally, firearms possession is not a politicized issue that would be debated during Czech elections. The 2014 European Parliament election became an exception in connection with the Swedish European Commissioner Cecilia Malmström's initiative to introduce new common EU rules that would significantly restrict the possibilities of legally owning firearms.[16]

In connection with that, a Czech gun owners association asked the parties running in the elections in the Czech Republic whether they agree (1) that the citizens should have the right to own and carry firearms, (2) that the competence on deciding firearms issues should lie in the hands of the nation states and not be decided on the EU level, and (3) whether they support Malmström's activity leading to the curbing of the right of upstanding citizens to own and carry firearms. Out of 39 parties running, 22 answered. The answers were almost unanimously positive to the first two questions and negative to the third one. Exceptions were only two fringe parties, the Greens – which, while supporting the right for gun ownership in its current form, also support further unification of rules on the European level and labeled the opposing reaction to Malmström's proposal as premature, and the Pirates which support unification of the rules leading to less restrictions elsewhere, commenting that one may not cross the borders out of the Czech Republic legally even with a pepper spray. Other fringe parties at the same time voiced their intent to introduce American style castle doctrine or to arm the general population following the example of the Swiss militia.[17]

2015 European Union "Gun Ban" Directive

A sticker promoting petition against EU Gun Ban on a lamp post at the National Monument in Vitkov, Prague.

The European Commission proposed a package of measures aimed to "make it more difficult to acquire firearms in the European Union" on 18 November 2015.[18] President Juncker introduced the aim of amending the European Firearms Directive as a Commission's reaction to a previous wave of Islamist terror attacks in several EU cities. The main aim of the Commission proposal rested in banning B7 firearms (and objects that look alike), even though no such firearm has previously been used during commitment of a terror attack in EU (of 31 terror attacks, 9 were committed with guns, the other 22 with explosives or other means. Of these 9, 8 cases made use of either illegally smuggled or illegally refurbished deactivated firearms while during the 2015 Copenhagen shootings a military rifle stolen from the army was used.)[19]

The proposal, which became widely known as the "EU Gun Ban",[20][21][22][23] would in effect ban most legally owned firearms in the Czech Republic, was met with rejection:

- Government Resolution No. 428/2016 of 11 May 2016[24]

- The Government tasks the Prime Minister, the First Vice-Prime Minister for Economy and Minister of Finance, Minister of Interior, Minister of Defense, Minister of Industry and Trade, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Labor and Social Affairs to (1) conduct any and all procedural, political and diplomatic measures necessary to prevent adoption of such a proposal of European Directive, that would amend the Directive No. 91/477/EEC in a way which would excessively affect the rights of the citizens of the Czech Republic and which would have negative effect on internal order, defense capabilities and economical or labor situation in the Czech Republic and (2) enforce such changes to the proposal of directive that would amend the directive no. 91/477/EEC that will allow preservation of the current level of civil rights of citizens of the Czech Republic and which will prevent negative impact on internal order, defense capabilities and economical and labor situation in the Czech Republic.

- Resolution of Chamber of Deputies No. 668/2016 of 20 April 2016[25]

- The Chamber of Deputies (1) expresses disapproval with the European Commission proposal to limit the possibility of acquisition and possession of firearms that are held legally in line with national laws of EU Member States, (2) refuses European Commission's infringement into a well established system of control, evidence, acquisition and possession of firearms and ammunition laid down by the Czech law, (3) expresses support for establishment of any and all functional measures to combat illegal trade, acquisition, possession and other illegal manipulation with firearms, ammunition and explosives, (4) refuses European Commission's persecution of Member States and their citizens through unjustified tightening of legal firearms possession as a reaction to terror attacks in Paris and (5) recommends the Prime Minister to conduct any and all legal and diplomatic steps to prevent enactment of a directive that would disrupt the Czech legal order in the area of trade, control, acquisition and possession of firearms and thus inappropriately infringe into the rights of the citizens of the Czech Republic.

- Senate Resolution No. 401/2016 of 20 April 2016 [26]

- Senate (…) (2) points out that the Commission’s directive proposal should be primarily aimed at illegal acquisition and possession of firearms, their proper deactivation and illegal firearms trade, as it is illegal firearms that are used during terror attacks, not firearms possessed in line with law of Member States and thus (3) disagrees with measures proposed in the directive that would lead to limitation of legal firearms owners and to disruption of internal security of the Czech Republic without having any clear preventive or repressive impact on persons possessing firearms illegally; such measures are contrary to the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality (...)

- Joint Declaration of Ministers of the Interior of Visegrád Group of 19 January 2016[27]

- The Ministers are fully aware of the need to fight actively against terrorism. As regards the regulation of the possession of firearms, it is necessary to focus the adopted measures primarily on illegal firearms, not legally-held firearms. Illegal firearms represent a serious threat. Within the European Union, it is necessary to prevent infiltration of illegal firearms from the risk areas. It should be taken into account that bans on possession of certain types of firearms that are not, in fact, abused for terrorist acts can lead to negative consequences, especially to a transition of these firearms into the illegal sphere. The V4 states have profound historical experience with such implications.

Ministry of Interior published in May 2016 its Impact Assessment Analysis on the proposed revision of directive No. 91/477/EEC. According to the Ministry, the main impacts of the proposal, if passed, would be:[28]

- Risks to internal security: According to Czech Ministry of Interior, the main danger of the proposal rested in massive transfer of now legal firearms into illegality, with up to hundreds of thousands of legal firearms entering black market. While the original Commission proposal would affect 40,000 – 50,000 firearms legally possessed by Czech citizens, Dutch EU Council Presidency proposal of 4 April 2016 would affect some 400,000 legally owned firearms, i.e. making half of all Czech legally owned firearms illegal with large proportion of gun owners likely refusing to surrender their firearms. The proposal as such is in direct contradiction with Ministry's long-term objective of lowering of number of illegal firearms and of conducting effective supervision of firearm owners.

- Risk to defensive capabilities: Security forces are not changing armaments annually, and thus small arms manufacturers need civilians as key customers. Crippling of civilian firearms market would likely lead to end of firearms manufacturing in the Czech Republic. At the same time, familiarity with semi-automatic versions of army rifles by civilians is a clear defensive advantage in case these people need to be drafted to defend the country.

- Threat to national culture: The proposal would lead to permanent deactivation of firearms owned by collectors and museums, including army museums, even though there is no empirical data supporting need for such a measure.

- Rise of unemployment: The proposal would lead to cancellation of tens of thousands of work places in the Czech Republic alone.

- Impact on hunting: Semiautomatic rifles have been purposefully used for hunting in the Czech Republic since at least 1946 and they are especially effective and popular in curbing wild boar overpopulation that is responsible for large number of car accidents as well as damage to agriculture. Banning of these firearms would likely lead to increase of car accidents due to collisions with wild animals and consequent increase in number of injuries and fatalities.

- Impact on state budget: As Czech constitution does not allow confiscation without remuneration, the government would have to pay up to tens of billions Czech crowns (billions of Euros) as compensation for banned firearms. Meanwhile, rise in unemployment would further impact budget income.

Despite reservations of the Czech Republic and Poland, the Directive was adopted by majority vote of the European Council and by first reading vote with no public debate in the European Parliament. It was published in the Official Journal under No. (EU) 2017/853 on 17 May 2017. Member States will have 15 months to implement the Directive into its national legal systems. The Czech Government announced that it will lodge a suit against the directive in front of the European Court of Justice, seeking postponement of its effectiveness as well as complete invalidation,[29] and did so on 9 August 2017.[30]

2016 Constitutional Amendment Proposal (rejected)

1. The security of the Czech Republic is provided by the armed forces, armed security corps, rescue corps and emergency services.

2. The state authorities, territorial governments and legal and natural persons are obliged to participate in the provision of security of the Czech Republic. The scope of duties and other details are set by law.

3. Citizens of the Czech Republic have the right to acquire, possess and carry arms and ammunition in order to fulfill the tasks set in subsection 2. This right may be limited by law and law may set further conditions for its exercise in case that it is necessary for protection of rights and freedoms of others, of public order and safety, lives and health or in order to prevent criminality.[31]

Failed proposal to amend Article 3 of Constitutional Act no. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic lodged by 36 MPs on 6 February 2017 (Subsection 1 & 2 are preexisting, subsection No. 3 was newly proposed in the Amendment.)]]

Ministry of Interior proposed a constitutional amendment on 15 December 2016 aimed at providing constitutional right to acquire, possess and carry firearms. The proposed law would, if passed, add a new section to Constitutional Act No. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic, expressly providing the right to be armed as part of citizen's duty of participation in provision of internal order, security and democratic order.[32]

According to explanatory note to the proposal, it aims at utilisation of already existing specific conditions as regards firearms ownership in the Czech Republic (2.75% of adult population having concealed carry license) for security purposes as a reaction to current threats – especially isolated attacks against soft targets. While there is constitutional right to self-defense, its practical utilization without any weapon is only illusory.[32]

The note further elaborates that unlike the rest of the EU, where most guns are owned for hunting, the vast majority of Czech gun owners possess firearms suitable for protection of life, health and property, explicitly mentioning, inter alia, semi-automatic rifles (which are subject to the proposed EU Gun Ban, see above).[32]

As regards adherence to EU law, the explanatory note states:[32]

- The proposal falls outside of jurisdiction of EU law, as

- Article 4(2) of TEU respects basic functions of state, including maintenance of public order and provision of national security.

- Article 72 of TFEU states that "This Title shall not affect the exercise of the responsibilities incumbent upon Member States with regard to the maintenance of law and order and the safeguarding of internal security."

- Article 276 of TFEU: "In exercising its powers regarding the provisions of Chapters 4 and 5 of Title V of Part Three relating to the area of freedom, security and justice, the Court of Justice of the European Union shall have no jurisdiction to review (...) the exercise of the responsibilities incumbent upon Member States with regard to the maintenance of law and order and the safeguarding of internal security."

- The proposal falls outside of scope of the Firearms Directive, as

- territorial authority of the proposal falls strictly within the Czech Republic

- personal authority of the proposal falls strictly on citizens of the Czech Republic and does not extend even to EU foreigners living in the country

- the proposal does not deal with acquisition of firearms for the purposes of hunting and sport shooting, which are the main areas that the Firearms Directive is concerned with

The Minister of Interior Milan Chovanec stated that he aims, due to pressing security threats, at having the proposal enacted before the autumn 2017 Czech Parliamentary Elections.[33] The right to be armed further became a major political issue with explicit impact as regards possible future Czech-EU relationship and membership, when the Civic Democratic Party took a pledge to "defend the right of law abiding citizens to be armed even if it would mean facing EU sanctions."[34]

On 6 February 2017, Minister Chovanec and 35 other Members of Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Parliament officially lodged proposal of the constitutional amendment with modified wording. In order to pass, the proposal must gain support of 3/5 of all Members of Chamber of Deputies (120 out of 200) and 3/5 of Senators present. Explanatory note to the proposal states that it aims at preventing significant negative impacts of proposed EU Firearms Directive amendment that would lead to transition of now legal firearms to black market. It aims to utilize to the maximum possible extent both exemptions of the Directive proposal as well as the sole authority of national law provided in the EU's primary law for issues of national security [31] The legislative process continued as follows:

- 27 February 2017: the proposal was discussed by the Government of the Czech Republic, showing a clear split between coalition parties as all 7 ČSSD Ministers supported the proposal, while ANO and KDU-ČSL Ministers either rejected it or abstained. Lacking majority in either way, the Government didn't take any official position on the proposal.[35] Legally, under the Article 44(2) of the Czech Constitution, failure to declare any opinion on a proposed act by Government means that the Government supports the proposal.[36] Government's position is only advisory.

- 12 April 2017: The proposal entered first reading in the Chamber of Deputies. There were altogether 57 entries of MPs and Ministers into the debate. None proposed vote for dismissal. The proposal was assigned to Constitutional Committee (143 votes out of 146 present) and to Security Committee (136 votes out of 147 present) to make an advisory recommendation. The Committees' time for deliberation was shortened to 54 days (98 to 25 outcome out of 147 present).[37]

- 19 April 2017: Following discussion, the Security Committee endorsed the proposal by a vote of 10 to 1.[38]

- 31 March 2017: The Constitutional Committee endorsed the proposal. Out of 12 present deputies, 11 supported it and 1 abstained from voting.[39]

- 7 June 2017: The proposal entered second reading in the Chamber of Deputies. With no motions for dismissal or for changes of the lodged text, the proposal moved to third reading in line with recommendation of the two Committees representatives, whose were the only entries into the debate concerning the proposal.[40]

- 28 June 2017: The proposal entered third and final reading in the Chamber of Deputies. After nearly 3 hours of debate, the proposal passed with 139 votes. Only 9 deputies voted against it. The proposal was supported by Social democrats (40 voted in favour, 3 abstained or didn't log in), ANO (39 voted in favour, 1 against, 3 abstained or didn't log in), Communist party (24 voted in favour, 1 against, 7 abstained or didn't log in), Civic Democrats (All 15 present deputies voted for) and the original Dawn of Direct Democracy deputies (9 voted in favour and 3 abstained or didn't log in).The support was much lower in TOP 09 (9 voted in favour, 2 against and 11 abstained or didn't log in) and especially KDU-ČSL (3 voted in favour, 5 against and 4 abstained).[41]

- 24 July 2017: The proposal was officially handed over from the Chamber of Deputies to the Senate. Before this happened, the Permanent Senate Committee for Constitution and Parliamentary Procedures adopted on 11 July 2017 Resolution No. 5 which labels the proposal as "useless and potentially harmful".[42] Out of 8 Senators and non-senate members of the committee present, 6 supported the Resolution proposed by Committee's chair and former Constitutional Court Justice Eliška Wagnerová. Two senators abstained.[43]

- 5 October 2017: A petition against the EU Gun Ban signed by over 100.000 citizens was debated during a public hearing in the Senate. Apart from the EU Directive, the debate largely centered on the proposed amendment.[44]

- The plenary session of the Senate postponed a vote on the proposal planned on 11 October 2017 to a later date.

- The Senate voted on the proposal on 6 December 2017. Only 28 out of 59 Senators present supported the proposal, failing to reach the 36 votes necessary. The proposal was thus sacked.[45] On the same day, the Senate adopted a resolution calling upon the Government not to implement parts of the EU Gun Ban that are not related to fighting terrorism, i.e. restrictions legal firearms that had not been used during commitment of any of terror attacks.[46]

The proposal was generally expected to be submitted again in Parliament after the 2018 autumn Senate elections, which ended with a decisive victory for ODS, a conservative party in favor of the amendment.[47] However, late President of the Senate, Jaroslav Kubera (ODS), claimed that it would had "no chance to pass", simply due to the general Senate tendency to avoid any changes to the Constitution and Constitutional, which was in place as opposition to the PM Andrej Babiš, who had expressed his plans to introduce significant constitutional changes).[48]

2021 Constitutional Amendment (approved)

(1) Everyone has the right to life. Human life is worthy of protection even before birth.

(2) Nobody may be deprived of her life.

(3) The death penalty is prohibited.

(4) Deprivation of life is not inflicted in contravention of this Article if it occurs in connection with conduct which is not criminal under the law. The right to defend own life or life of another person also with arms is guaranteed under conditions set out in the law.[49]

2021 Amendment of Article 6 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms, which was lodged by 35 Senators on 24 September 2019 (Text in italics was preexisting, the last sentence in subsection 4 was newly added in 2021.)

On 24 September 2019 a group of 35 Senators lodged formal proposal to amend the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms to include right to defend life with arms. The proposal was drafted by senator Martin Červíček (ODS), retired police brigadier general and 2012 - 2014 Police of the Czech Republic president.[49] The proposal was originally planned for debate during a Senate meeting in October 2019. The Senate may formally propose adoption of the amendment through a simple majority of votes. In order to pass, the proposal must then gain support of 3/5 of all Members of Chamber of Deputies (120 out of 200) and then be voted through the Senate again, this time with majority of at least 3/5 of Senators present.

Media dubbed the proposal "Czech Republic's second amendment" both in connection with the protection of the right to keep and bear arms in the US constitution and due to the fact that the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms had only been amended once since adoption in 1992.[50] The first amendment to the Charter had been adopted in 1998 and extended the maximum length of police custody without charges from original 24 hours to 48 hours.[51]

According to the Czech gun laws expert and attorney Tomáš Gawron the proposal bears no resemblance to the American second amendment. Unlike its US counterpart, the Czech proposal doesn't stipulate a restraint on Government's power, but only symbolically sets out significance of the mentioned right and otherwise leaves the Government a free hand in setting detailed conditions in law. By being mostly symbolic, the proposal is more similar to the article 10 of Mexican constitution. Also while the American second amendment centers on the right to keep and bear arms, the Czech proposal deals primarily with right of personal defense, including with arms.[52][53]

Senate voted to formally propose adoption of the Constitutional Amendment on 11 June 2020. 41 out of 61 senators voted for the measure. That was sufficient to start the legislative process, i.e. to submit the proposal for the vote at the Chamber of Deputies, for which a simple majority is needed. However the number fell one vote short of reaching constitutional majority. Constitutional majority must be reached once the amendment is accepted by the Chamber of Deputies and bill moved back to Senate for final approval.[54] The legislative process continued as follows:

- 13 July 2020: The Government formally recommended adoption of the proposal, which indicated support of Chamber majority. According to Government's formal opinion, the proposal does not bring material change into the legal system, only constitutionally confirms already existing legal state. The Government further pointed out that while Senate clearly aimed at firearms, due to proposal's wording it will cover all weapons, including knives, axes and other arms.[55]

- October 2020: During the 2020 Czech Senate election, the most vocal opponents of the proposal lost their bids for re-election. This significantly raised chances of reaching constitutional majority in the Senate.[56]

- 9 March 2021: Chamber of Deputies started formal debate on the proposal. It was assigned for consideration to the Constitutional Committee (83 votes out of 90 present, none against) and to the Security Committee (69 votes out of 91 present, none against). Proposal by a deputy from the Czech Pirate Party to assign the proposal also to the Permanent Committee on Constitution was rejected (35 votes out of 95 present, 9 against).[57]

- 18 March 2021: Security Committee of the Chamber of Deputies endorsed the proposal and recommended its adoption.[58]

- 28 April 2021: Constitutional Committee of the Chamber of Deputies endorsed the proposal and recommended its adoption.[59]

- 2 June 2021: The proposal entered second reading in the Chamber of Deputies. Pirate Party member Vojtěch Pikal entered a proposal for a change, whereby instead of adding the aforementioned sentence into Article 6(4) of the Charter, a new Article 41(3) would be added into the Charter: "The right to defend basic rights and freedoms also with arms is guaranteed under conditions set out in the law."[60][61] The proposal for a change was labeled as better than original amendment proposal, however with lower chances of passing through the Senate.[62]

- 9 June 2021: Constitutional Committee recommended adoption of the original amendment proposal and rejection of Pirate Party Vojtěch Pikal's proposal for a change.[63]

- 18 June 2021: The proposal entered third (final) reading in the Chamber of Deputies. Out of 159 deputies present, 141 deputies supported the proposal, only 3 deputies voted against it; the remaining 14 abstained. The proposal thus reached the constitutional majority of 120 votes.[64]

- 14 July 2021: Senate's Constitutional Committee endorsed the proposal and recommended its adoption.[65]

- 14 July 2021: Senate's Committee for Foreign Affairs, Defense and Security endorsed the proposal and recommended its adoption.[66] Seven members voted for adoption (Patrik Kunčar (KDU-ČSL), Jaroslav Zeman (SLK), Marek Ošťádal (STAN), Tomáš Czernin (TOP 09), Tomáš Jirsa (ODS), Ladislav Faktor (independent) a Jan Sobotka (independent for STAN)), two against (Pavel Fischer (independent) a Miroslav Balatka (independent for STAN))[67]

On 21 July 2021, the Senate approved the amendment by the majority of 54 of 74 present, i.e. significantly more than the 45 votes necessary. 13 Senators voted against, 7 abstained.[68] The bill was signed by the President on 3 August 2021[69] and published in the collection of laws on 13 August 2021 under No. 295/2021. It became effective on 1 October 2021.[70]

2021 Firearms Act amendment

The right to acquire, keep and bear firearm is guaranteed under conditions set by this law.

Article 1 Subsection 1 of the Czech Firearms Act added in 2021.

The Czech Republic was bound to implement the 2017 EU Firearms Directive. Originally, it was considered unworkable with the existing Czech firearms act. The government took a decision to adopt a completely new firearms law, which would fulfill the EU requirements while preserving rights of the Czech citizens. As the works on an entirely new enactment stalled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Parliament then amended the existing 2002 Firearms Act, using many of the concepts developed for the intended new law in the mere amendment instead.[71]

The 2021 amendment brought sweeping changes, which include a new permitting process for magazines with capacity of more than 10 (long guns) or 20 rounds (short guns), change in firearms classification, or duty to register new types of guns (e.g. gas pistols, flobert guns, etc.). Interpretation of the new changes is subject to a new introductory sentence in Article 1 Subsection 1 of the Firearms Act.[72]

At the same time rules were eased in a number of ways. Mechanical weapons (crossbows, bows) and night vision scopes became completely unregulated. Silencers, hollow point and simunition ammo became available to gun license holders. Tasers, which were previously restricted, became available without gun license. A change in open carry rules positively affected biathlon and reenactment societies.[72]

A new provision allowed Government to arrange concealed carry reciprocity with other EU Member States.[72]

References and sources

- ↑ Šimek, Jiří (18 December 2012). "Statistika držitelů zbrojních průkazů a počtu registrovaných zbraní 1990-2010" (in Czech). Gunlex. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ "Gun license statistics between 2003–2012" (in Czech). Gunlex. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "V ČR loni mělo zbrojní průkaz 292.000 lidí, jejich počet klesl" (in Czech). ČTK. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gawron, Tomáš (January 2021). "Unikátní české výročí: 600 let civilního držení palných zbraní [Unique Czech anniversary: 600 years of civilian firearms possession]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gawron, Tomáš (November 2019). "Historie civilního držení zbraní: Zřízení o ručnicích – česká zbraňová legislativa v roce 1524 [History of civilian firearms possession: Enactment on Firearms - Czech firarms legislation in 1524]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ↑ Eurobarometer, Directorate General for Communication (2013), Flash Barometer 383: Firearms in the European Union – Report (PDF), Brusselss, retrieved 26 March 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Gawron, Tomáš (10 January 2021). "Zbraňové statistiky 2020: Počet legálních držitelů se zvýšil o 0,63%, palnou zbraň pro osobní ochranu smí nosit čtvrt milionu lidí [Firearms statistics 2020: The number of legal gun owners grew by 0,63%, quarter million people can carry a gun for personal protection]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ↑ Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1975), A History of the Crusades: The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Univ of Wisconsin Press, p. 604, ISBN 9780299066703

- 1 2 Verney, Victor (2009), Warrior of God: Jan Zizka and the Hussite Revolution, Frontline Books

- ↑ Titz, Karel (1922). Ohlasy husitského válečnictví v Evropě. Československý vědecký ústav vojenský.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "howitzer". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ The Concise Oxford English Dictionary (4 ed.). 1956. pp. Howitzer.

- ↑ Hermann, Paul (1960). Deutsches Wörterbuch (in German). pp. Haubitze.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kalousek, Štěpán (2009). Právní úprava držení zbraní v 18. a 19. století [Regulations concerning firearms possession in 18th and 19th century] (in Czech).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sedláček, Petr (2010). Právní úprava držení a nošení zbraní v letech 1945–1989 [Laws concerning firearms possession and carry between 1945 and 1989] (Thesis) (in Czech). Masarykova univerzita, Právnická fakulta.

- ↑ "Firearms and the internal security of the EU: protecting citizens and disrupting illegal trafficking" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "Volby do Evropského parlamentu 2014 [2014 Elections to the European parliament]" (in Czech). gunlex.cz. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "European Commission strengthens control of firearms across the EU". European Commission. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ↑ "Le B7? Mai usate!". armietiro.it. 27 November 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ↑ "Finland seeks exception from EU gun ban". Reuters. 16 December 2015.

- ↑ "EU Gun Ban : Intervention Suisse à Bruxelles". ASEAA. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ "Trilog schließt die Verhandlungen zum "EU-Gun ban"". Firearms United. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ "Gun lobby stirs to life in Europe". Politico. 5 April 2016.

- ↑ "USNESENÍ VLÁDY ČESKÉ REPUBLIKY ze dne 11.května 2016 č. 428 k Analýze možných dopadů revize směrnice 91/477/EHS o kontrole nabývání a držení střelných zbraní". Czech Government. Retrieved 4 December 2016. "Vláda (...) II. ukládá předsedovi vlády, 1. místopředsedovi vlády pro ekonomiku a ministru financí, ministrům vnitra, obrany, průmyslu a obchodu, zahraničních věcí, zemědělství a ministryni práce a sociálních věcí 1. podniknout veškeré procesní, politické a diplomatické kroky k zabránění přijetí takového návrhu směrnice, kterou se mění směrnice 91/477/EHS, který by nepřiměřeně zasahoval do práv občanů České republiky a měl negativní dopady na vnitřní pořádek, obranyschopnost, hospodářskou situaci nebo zaměstnanost v České republice, 2. zasadit se o prosazení takových změn návrhu směrnice, kterou se mění směrnice 91/477/EHS, které umožní zachování současné úrovně práv občanů České republiky a umožní předejít negativním dopadům na vnitřní pořádek, obranyschopnost, hospodářskou situaci nebo zaměstnanost v České republice."

- ↑ "usnesení Poslanecké sněmovny". Czech Parliament. Retrieved 4 December 2016. "Poslanecká sněmovna 1. v y j a d ř u j e n e s o u h l a s se záměrem Evropské komise omezit možnost nabývání a držení zbraní, které jsou drženy a užívány legálně v souladu s vnitrostátním právem členských zemí Evropské unie; 2. o d m í t á , aby Evropská komise zasahovala do funkčního systému kontroly, evidence, nabývání a držení zbraní a střeliva nastaveného právním řádem České republiky; 3. v y j a d ř u j e p o d p o r u vytvoření všech funkčních opatření, které povedou k potírání nelegálního obchodu, nabývání, držení a jiné nelegální manipulace se zbraněmi, střelivem a výbušninami; 4. o d m í t á , aby Evropská komise v reakci na tragické události spojené s teroristickými činy v Paříži perzekvovala členské státy a jejich občany neodůvodněným zpřísněním legálního držení zbraní; 5. d o p o r u č u j e p ř e d s e d o v i v l á d y Č e s k é r e p u b l i k y , aby podnikl všechny právní a diplomatické kroky k zabránění přijetí takové směrnice, která by narušovala český právní řád v oblasti obchodu, kontroly, nabývání a držení zbraní a tím nevhodně zasahovala do práv občanů České republiky."

- ↑ "401.USNESENÍ SENÁTU z 22. schůze, konané dne 20. dubna 2016". Czech Senate. Retrieved 4 December 2016. " 2. upozorňuje však, že v návrhu směrnice se Komise měla zaměřit primárně na nelegální nabývání a držení střelných zbraní, jejich řádné znehodnocování a na nedovolený obchod s nimi, neboť k teroristickým útokům jsou využívány právě nelegální zbraně, nikoli zbraně držené v souladu s právními předpisy členských států; 3. nesouhlasí proto s opatřeními obsaženými v návrhu směrnice, která by vedla k omezení legálních držitelů střelných zbraní a narušení vnitřní bezpečnosti České republiky, aniž by to mělo zjevný preventivní či represivní účinek na osoby držící zbraně nelegálně; taková opatření by byla v rozporu se zásadami subsidiarity a proporcionality"

- ↑ "Joint Declaration of Ministers of the Interior Meeting of Interior Ministers of the Visegrad Group and Slovenia, Serbia and Macedonia". Visegrad Group. 19 January 2016.

- ↑ "Analýza možných dopadů revize směrnice 91/477/EHS o kontrole nabývání a držení střelných zbraní". Czech Ministry of Interior. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ↑ "ČR podá žalobu proti směrnici EU o zbraních [CR will file suit against he European Firearms Directive]". Ministry of Interior. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ↑ "Czechs take legal action over EU rules on gun control". Reuters. 9 August 2017.

- 1 2 36 Members of Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic (2017), Proposal of amendment of constitutional act no. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic (in Czech), Prague, retrieved 12 February 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 Ministry of Interior (2016), Proposal of amendment of constitutional act no. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic (in Czech), Prague, retrieved 16 December 2016

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Adamičková, Naďa (15 December 2016). "Lidé mají dostat právo sáhnout při ohrožení státu po zbrani [People shall have the right to use firearms for protection of state]" (in Czech). novinky.cz. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "Budeme bránit držení zbraní, i kdyby od EU hrozily sankce, slibuje ODS [ODS pledged to defend right to be armed even if it would lead to EU sanctions]". Mladá fronta DNES (in Czech). 17 January 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ "Vláda se na zákonu ke zbraním neshodla, rozhodne Parlament [Government didn't reach consensus on the firearms law, Parliament shall decide]" (in Czech). ceskenoviny.cz. 27 February 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (1993), Act No. 1/1993 Coll., The Constitution of the Czech Republic (in Czech), Prague

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Art 44(2) - ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (2017), Stenografický záznam z jednání poslanecké sněmovny dne 12. dubna 2017 [Stenographic recording of debate of the Chamber of Deputies on 12 April 2017] (in Czech), Prague

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Poslanci se pohádali o právo občanů na použití zbraně [MPs argued about the citizens' right to use firearms]" (in Czech). ceskenoviny.cz. 19 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ "Sněmovní výbory: Majitelé legálně držených zbraní by měli dostat právo zasáhnout [Chamber of Deputies Committees: Gun owners shall gain the right to take action]" (in Czech). forum24.cz. 2 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (2017), Stenografický záznam z jednání poslanecké sněmovny dne 12. dubna 2017 [Stenographic recording of debate of the Chamber of Deputies on 12 April 2017] (in Czech), Prague

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ http://www.psp.cz/sqw/hlasy.sqw?G=66611 (Final vote on Czech constitutional act on security amendment, 28 June 2017)

- ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (2017), 5.USNESENÍ, k návrhu novely ústavního zákona č. 110/1198 Sb., o bezpečnosti České republiky, ve znění pozdějších předpisů [Resolution No. 5, concerning the proposal for amendment of the Constitutional Act on Security of the Czech Republic] (in Czech), Prague

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (2017), Stálá komise Senátu pro Ústavu ČR a parlamentní procedury – Zápis z 5. schůze, konané dne 11. července 2017 od 11 hod. [Permanent Senate Committee for Constitution and Parliamentary Procedures – Minutes of 11 July 2017 Meeting] (in Czech), Prague

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Petice odmítá regulaci zbraní, označuje ji za diktát ze zahraničí [A petition against gun regulation calls it a foreign dictat] (in Czech), 2017, retrieved 5 October 2017

- ↑ Právo nosit zbraň pro zajištění bezpečnosti Česka Senát neschválil [The Senate didn't adopt the right to carry a firearm for the purpose of protection of the Czech Republic] (in Czech), 2017, retrieved 6 December 2017

- ↑ Senát odmítl některé části směrnice EU o regulaci zbraní. Žádá výjimky [The Senate refused some parts of the EU Firearms Directive, asks for exemptions] (in Czech), 2017, retrieved 6 December 2017

- ↑ "Rozhovor – senátorka Syková: implementace by se měla řešit až po rozsudku Evropského soudního dvora [Senator Syková: Implementation should be postponed after the decision of the CJEU]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). 28 June 2018.

- ↑ "Rozhovor – předseda Senátu J. Kubera: Změna Ústavy zakotvující civilní držení zbraní v současnosti nemá šanci projít". 14 February 2019.

- 1 2 35 Members of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic (2019), Proposal of amendment of Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (in Czech), Prague, retrieved 29 September 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Harsanyi, David (2020-07-23). "It Looks Like the Czech Republic Might Get a Second Amendment". National Review. Retrieved 2021-05-09.

- ↑ Constitutional Act No. 162/1998 Coll.

- ↑ Gawron, Tomáš (13 October 2019). "Ústavní změna: Co (ne)čekat od mexického doplnění Listiny o právo na obranu se zbraní "za podmínek, které stanoví zákon" [Constitutional change: What (not) to expect from Mexican addition of the Charter with right to defend self with arms "under conditions set out by the law"]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ↑ Gawron, Tomáš (19 July 2020). "Předložená "zbraňová" novela Listiny je potřebná, vhodná a přichází v pravý čas [Proposed "firearms" amendment of the Charter is needed, appropriate and comes at the right time]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ Senate meeting No. 24, vote No. 31 held on 11. June 2020.

- ↑ Government opinion to the Proposal No. 895

- ↑ Voters' revenge, Parlamentní Listy, 7 October 2020

- ↑ Minutes of Chamber of Deputies Session on 9 March 2021, 7 PM onwards

- ↑ Resolution No. 205 of the 51st meeting of the Security Committee held on 18 March 2021

- ↑ Resolution No. 272 of the 87th meeting of the Constitutional Committee held on 28 April 2021

- ↑ Minutes of the Meeting of the Chamber of Deputies on 2 June 2021, Article 21

- ↑ Proposal for change No. 8564 by Vojtěch Pikal

- ↑ Gawron, Tomáš (9 June 2021). "Analýza "pirátského" pozměňovacího návrhu k "zbraňové" novele Listiny předloženého posl. Vojtěchem Pikalem [Analysis of "pirate" proposal for a change of the "arms" amendment of the Charter authored by MP Vojtěch Pikal]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ [Resolution No. 289 of the 92nd meeting of the Constitutional Committee held on 9 June 2021]

- ↑ "Poslanci podpořili sebeobranu se zbraní v ruce jako základní lidské právo. Novelu musí potvrdit Senát | Domov". 18 June 2021.

- ↑ Senate's Constitutional Committee Resolution No. 74 of 14 July 2021

- ↑ Senate's Committee for Foreign Affairs, Defense and Security Resolution No. 76 of 14 July 2021

- ↑ "Fischer nechtěl, ale smůla. Kolegy přehlasován. Majitelé zbraní o krok blíže".

- ↑ "Senát schválil ústavní právo bránit sebe i jiné se zbraní | ČeskéNoviny.cz".

- ↑ "Prezident republiky podepsal šest zákonů".

- ↑ https://aplikace.mvcr.cz/sbirka-zakonu/ViewFile.aspx?type=c&id=39197

- ↑ Gawron, Tomáš (23 October 2020). "Od směrnice k implementaci: co přináší a co znamená Poslaneckou sněmovnou PČR schválená novela zákona o zbraních [From directive to implementation: what is the meaning of the Firearms Act amendment adopted by the Chamber of Deputies]". Advokátní deník (in Czech). Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 Gawron, Tomáš (22 December 2020). "Přehledně: Jaké změny přináší novela zákona o zbraních [What changes are coming with the Firearms Act Amendment]". zbrojnice.com (in Czech). Retrieved 22 December 2020.