The history of Sacavém is the history of a town that, due to its strategic location —at the crossroads of the roads leading to Lisbon from the north and east— has been present in almost all the key dates of Portuguese history. Sacavém is a freguesia belonging to the municipality of Loures, very close to the municipality of Lisbon, crossed by the Trancão river and bordered to the south by the Mar da Palha.

It is a very ancient population, existing in Roman times a bridge that survived, at least, until the 16th century (according to Francisco de Holanda). From the time of the Moorish occupation remained, apparently, the toponym of Arab origin (شقبان, Šaqabān); immediately after the siege and subsequent conquest of Lisbon by the Christians in 1147, it seems that a battle took place in this locality (the Battle of the River Sacavém), although today it is considered legendary.

During the Middle Ages, Sacavém was a royal manor, whose beneficiaries were the admiral Manuel Pessanha, the queen Dª Leonor Teles and later the constable Nuno Álvares Pereira. After the latter's death, the property passed to the House of Bragança, under whose rule it would remain until the Revolution of October 5, 1910 and the proclamation of the Portuguese Republic.

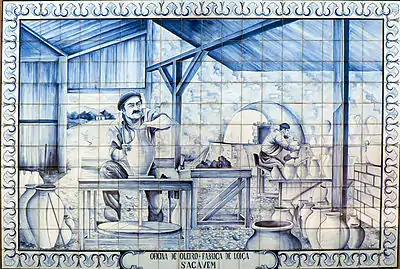

Severely damaged by the earthquake of 1755, Sacavém began a slow decline that lasted for about a century, until 1850, when its industrialisation began —with the creation of the famous Sacavém tile factory, which spread the name of the city throughout the country and abroad— as well as the construction of the railroad. This situation contributed to a population increase until the mid-70s of the 20th century, which also favored the development of several associations and sports clubs.

At the end of the 80's, the parish obtained its current geographical configuration, with the separation of Portela de Sacavém and Prior Velho. On June 4, 1997, Sacavém finally saw all its potential value recognized, being elevated to the category of town. Months later, the Vasco da Gama Bridge was inaugurated, connecting the city to Montijo, becoming a landmark in the city's urban landscape.

Prehistory, Roman and Germanic rule

Neolithic / Copper Age

Human presence in the Sacavém region has been proven for several centuries. About this, Pinho Leal wrote in his monumental work Portugal Antigo e Moderno (Ancient and Modern Portugal):

"Sacavém is undoubtedly a very ancient population, and already existed in Roman times."[1]

In fact, it seems to have been occupied already in prehistoric times (during the Neolithic period and, most probably, during the Copper Age, from when there seem to date three polished stone axes[2]); there is news of the existence of a cave under the Largo do Terreirinho, next to the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Health, which, when excavated during the 80's of the 20th century revealed the existence of prehistoric vestiges.[3]

Roman occupation

.jpg.webp)

At the end of the 3rd century B.C., the Romans arrived in the Iberian Peninsula. OLISSIPO (the ancient name of Lisbon), allied with the Roman legions, was quickly absorbed by the Empire, and rewarded with the attribution of the status of MVNICIPIVM (that is, full citizenship, being for that reason exempt from the payment of taxes to which other territories conquered by force of arms were subjected) and the name of FELICITAS IVLIA (in honor of Julius Caesar).

Administratively, the municipality was integrated in the CONVENTVS SCALLABITANVS. The latter was part of the province of HISPANIA VLTERIOR and, from 27 B.C. (by the division decreed by Augustus), of the LVSITANIA, with capital in AVGVSTA EMERITA (corresponding to the current Mérida, in Extremadura, Spain).

This MVNICIPIVM covered an extensive rural territory, covering a distance of approximately 50 kilometers around the urban area (which was destined to its self-sufficiency), so logically the place where the present Sacavém stands was integrated in it.

About Sacavém in particular, it can only be stated with certainty that in the 1st century a common section of two Roman roads passed through it:

- VIA XV, which linked OLISSIPO with the provincial capital of AVGVSTA EMERITA, passing through the city of SCALLABICASTRVM, the modern Santarém, at the time capital of the CONVENTVS SCALLABITANVS;

- VIA XVI, which linked OLISSIPO with BRACARA AVGVSTA, capital of the CONVENTVS BRACARENSIS, in the province of GALLÆCIA, corresponding to modern Braga.

Even today there are still traces of this road network under the pavement of the streets António Ricardo Rodrigues and José Luís de Morais (which later would constitute the fundamental factor that led to the urbanization of the town, linking Sacavém de Cima and Sacavém de Baixo).[4]

The importance of Sacavém and its river can already be appreciated at this time; in fact, the Romans would have built a bridge over the Trancão River, which would still exist in the 17th century, according to several stories —especially those of Francisco de Holanda (who alludes to it in his work Da Fábrica que Falece à Cidade de Lisboa, of 1571, in which he points out the need of the king —at the time D. Sebastian— to proceed with the reconstruction of the bridge, making a sketch of it in which it is represented by 15 arches, so historians assume that the flow of the river was greater in antiquity[5]) and Miguel Leitão de Andrada (in the "2nd Dialogue" of his Miscelânea, dated 1629). This bridge (currently the central element of the town's coat of arms) was the natural continuation of the route followed by the aforementioned roads, linking Sacavém to the north bank of its river.

If it is admitted that the famous Itinerary of Antoninus was based on routes taken by Antoninus Pius, and considering the fact that the aforementioned roads are mentioned in the work, it is natural that the emperor would have passed through the town and its bridge over the Trancão.

There are reports that in Sacavém there was a stone inscription (whose whereabouts are currently unknown) that read as follows:

SILVIVS

MAG • I • TER

F • DAR • MAG

P • E • LIIII • P • V

A plausible translation of this supposed inscription, which was probably found on a monument, has not been possible.[6]

Alans and Visigoths

The Romans were followed by the occupation of the barbarian peoples, during their migrations towards the west: first the Alans settled (occupying the entire southwest of the peninsula for five years, leaving no trace of their presence in the area), and then the Visigoths (who would have built a chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Pleasures in the current Sacavém, on whose ruins the current Church of Our Lady of Victory is built).[7]

Muslim domination

.jpg.webp)

Conquest and cohabitation

From 711, a new era in the history of the Iberian Peninsula began, the Muslim occupation. Lisbon (al-Ušbuna) was taken in 716 by Berber forces under the orders of Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa ibn Nusayr (who at the time was governor of Andalus on behalf of the Caliph of Damascus, being the son of the governor of the province of Ifriquia, Musa ibn Nusayr), falling during the same year the populations that integrated the term of Lisbon (among which is Sacavém), as well as other nearby locations such as aš-Šantara (Sintra).

As happened in the other regions of the Ġarb al- ndalus (the "West of Ándalus", a region that roughly corresponds to the ancient Roman Lusitania and therefore included most of modern Portugal), a significant number of Hispano-Romans and Visigoths in the region of al-Ušbuna, although they had become Arabized (becoming bilingual in Arabic —the new language of the administration— and in medieval Vulgar Latin, maintaining as a language of worship), they did not Islamize (or did so late) and maintained their Christian faith; among them would be some inhabitants of the Sacavém area who, according to tradition, were able to maintain their worship in the Church of Our Lady of the Pleasures, in exchange for the payment of the jizya,[7] thus becoming Mozarabs, that is, Christians living under Moorish rule and their highest authority being the Mozarabic bishop of Lisbon — something that was possible due to the religious tolerance that was preached in Classical Islam for the so-called "People of the Book" (Ahl al-Kitab), that is, Jews and Christians.

It is believed that the medieval tower of Sacavém de Cima, located in Largo do Terreirinho, in front of the Chapel of Our Lady of Health, in the historic center of the town, has Muslim origins and it would be there where, according to tradition, the Christians paid the yizia to the Moorish authorities. Although restoration work was carried out during the Middle Ages, it is currently in a semi-ruinous state.[8]

Sacavém in al-Andalus

According to the description of a Muslim source (the Syrian geographer Abu Abdallah Yaqut ibn-Abdallah al-Rumi al-Hamawi), Sacavém was "one of the towns of Lisbon, to the east of it", being the locality classified as a qarya (word that can be translated, precisely, as al-qarīa, small village, town, village).[9]

Like several other small towns around Lisbon, Sacavém was administratively integrated into the Kura of al-Ušbuna (the kura being a Muslim territorial administrative unit, which basically coincides with the same geographical delimitation of the ancient Roman CONVENTI, encompassing several localities although with differences in the powers attributed), leading it was a qadi, a governor with military functions appointed, first by the wali of Cordoba, the capital of al-Andalus, as representative of the caliph of Damascus, and later by the emirs (756-929) and then by the Umayyad caliphs (929-1031) who ruled al-Andalus from that city.

Throughout the Emirate and Caliphate domination, several seditions against the Umayyads took place in Ġarb al- ndalus (where it was included, as previously explained, Sacavém), highlighting the revolt promoted by the Banu Marwan of Mérida/Badajoz or that of Umar ibn Hafsun, of Bobastro, put down in the late 20s of the 10th century (in fact, during the second half of the 9th century and until January 929, date in which 'Abd al-Raḥman III proclaims himself Amir al-Mu'minin (Prince of the Believers), that is, Caliph —precisely after defeating the Banu Marwan—, passing into a period of greater weakness of the central power, the Gharb was only nominally part of the Umayyad emirate, having become a sort of autonomous principality with headquarters in Batalyaws, that is, Badajoz).

Some time later, during the final upheavals that led to the fall of the caliphate in 1031, and subsequently to the formation of the taifa kingdoms, Sacavém ended up being integrated into the kingdom of Badajoz (except for a small temporary lapse in the 1020s when there was a taifa based in Lisbon under 'Abd al-Aziz ibn Sabur and 'Abd al-Malik ibn Sabur, sons of Sabur al-Khatib, a former servant of Slavic origin, who served the caliph al-Hakam II and who launched the revolt call of the Ġarb al-Andalus against the caliphate in 1009, ruling the taifa of Badajoz until he was deposed by the Banu'l-Aftas), after which he returned sovereignty to the Aftasid king of Badajoz.

In 1093, in exchange for help against the Almoravid invaders from the Maghreb, the emir of Badajoz ceded to the Imperator totius Hispaniae, Alfonso VI of León and Castile, possession of the castles of al-Ušbuna and aš-Šantaryin (Santarém), with Santarém passing into Christian hands. The Leonese dominion was short-lived: in 1095, in the face of the inexorable advance of the Almoravid troops led by Yusuf ibn Tašfin, Count Raymond of Burgundy was defeated and the border passed from the Tagus to the Mondego River, returning Sacavém to Muslim hands.

In the end, the domain of the Almoravid rigorists, although strong during the first years, was already in deep decline shortly before the final conquest of Lisbon in October 1147 by Alfonso I of Portugal; from 1144, the entire Garb, led by Ibn Qasi, rose up against Almoravid rule, beginning the so-called period of the second taifas. The Tagus valley was united to form the taifa of Santarém — ephemeral, since its end came three years later, with the Christian reconquest of the two main border towns of the Tagus by the Portuguese.

Al-Šaqabāni, or el Sacavenense

According to the aforementioned Yaqut al-Hamawi, related to Sacavém is the poet and mystic Taytal ibn Isma'īl, called al-Šaqabāni (literally, e Sacavenense), of whom some fragments of poems are preserved.

Al-Šaqabāni, who had studied in Córdoba, capital of the homonymous Caliphate, became a mystic linked to Sufism (a contemplative current within Islam that seems to have had great diffusion among the inhabitants of Ġarb al-Ándalus — for example, Ibn Marwan, the fortifier of Marvão), instituting a ribat[10] in Šaqabān, intended for Jihad (a concept that is not related to the external struggle, considering the propagation of the Islamic faith, but with the struggle on a personal level, of the believer himself in order to achieve his total self-control),[11] leaving then to a barren place in the vicinity where he founded an az-zāwiya (which in Portuguese came to be called azóia and possibly this is the origin of the toponym of the neighboring Santa Iria de Azóia, then known as az-zāwiya at-Taytal, that is, Azóia de Taytal), where he would devote himself to mystical reflection.[12]

Technical and toponymic contributions

In addition to certain techniques to improve crops in the area (such as the use of the waterwheel), and the introduction of certain agricultural cultures (such as citrus fruits) throughout the peninsular territory, the main Muslim vestige in Sacavém is precisely its toponym (although another theory proposes that it is of French origin —obviously later theory, eventually from the time of the Reconquest— for the name of the freguesia).

Šaqabān, Sacabis

For a long time, philologists estimated that the term derived from the Arabic šaqabi (meaning "near" or "neighbor" — meaning from the city of Lisbon, which even then assumed considerable importance), Latinized in the third declension into sacabis, -is (which would form in the accusative sacabem, and from there would come the modern name "Sacavém"); However, they never managed to cite an Arabic source that corroborated such a theory.[13]

More recently, it was discovered, also in Yaqut's work (the Kitab Mu'jam al-Buldan or Book of Countries, c. 1228, a geographical description of the then known world), a more precise reference to the term used by the Arabs to designate the population — Šaqabān (in Arabic, شقبان), which closely resembles, no doubt, with the modern pronunciation.[12]

Çaca dé Uen

Also about the origin of the toponym Sacavén, the distinguished Portuguese linguist José Pedro Machado wrote, in his Diccionario Onomástico-Etimológico de la Lengua Portuguesa, that he had been thinking about the name of this town, saying that a Galician minstrel, Pedro Amigo de Sevilla (active in the court of Alfonso X of León and Castile, that is, in the second half of the XIII century), composed a Cantiga de escarnio (CBN n. No. 1687; CV no. 1199) in which he satirizes a fellow troubadour (Pedro García de Ambroa), scorning his pious intention of wanting to go to the Holy Places of Jerusalem on pilgrimage, but staying nonetheless for Sacavém... The Galician-Portuguese cantiga reads as follows:

Marinha Meiouchi, Pero d'Ambroa

diz el que tu o fuisti i pregoar

qué nunca foy na terra d'Ultra-mar;

mays non fezisti como molher boa,

ca, Marinha Meiouchi, sy hé sy,

Pero d'Anbroã sey eu ca foy lh'y,

mays queseste lh'y tu mal assacar.

Marinha Meiouchi, sen nulha falha

Pero d'Ambroã en 'Çaca dé Uen'

filhou a cruz pera Iherusalen

e, depois d'aquesto, sé Deus mi ualha,

Marinha Meiochi, com'é, romeu

que uen canssado é tal o ui end eu

tornar, é dizes que non tornou en.

Maria Meiouchi, muytas uegadas

Pero d'Anbroã ach end eu mal,

mays sé té colhé d el logar atal

com andas tu assy pelas pousadas,

Marinha Meiouchi, a mui gram sazon,

Pero d'Anbroã, se th achar enton,

gram med ey que ti querra fazer mal.

According to Machado, the locution Çaca dé Uen (read Saca dé Ven) would be a derivation of Sacavém, proposing the French origin of the term, a hypothesis generally preferred to the Arabic theory. In fact, during the Middle Ages there existed in Anjou (France) the wine brotherhood du Sacavin, a term derived precisely from saca (meaning wineskin to deposit wine, oil, or liquids in general), and vin (fr. for "wine"), a term that in certain French dialects (such as Angevin) is pronounced ven (/vẽ/), so that, if this thesis is accepted, Sacavém would mean "wine wineskin" — a hypothesis that, in spite of everything, is not at all far-fetched since the locality would become an important wine-producing place (like the rest of the circumcised region) throughout the Middle Ages.[14]

Reconquest

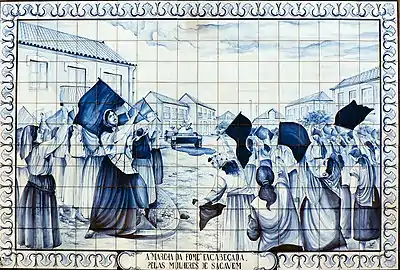

According to tradition, Sacavém was taken from the Moors by Alfonso I of Portugal in 1147, after the almost legendary Battle of Sacavém (whose first accounts date only from the 16th century, and which, although corrected in the 17th century, have been considered a myth since Alexandre Herculano[15]).

Middle Ages

XII century

After the conquest, Sacavém became a royal estate of the Portuguese Crown, undergoing a significant increase in agriculture; the main plantations of the population, as in the rest of Estremadura were Mediterranean, especially vineyards, olive trees and wheat. On the other hand, the exploitation of the salt mines, abundant in the territory until the 18th century, as well as the fluvial transport of several agricultural products from the interior of the territory of Lisbon to the future capital of the kingdom, would characterize the population of the coming centuries. In this context, a river port began to develop at the confluence of the Tagus and the Trancão, which was relatively important until the 18th century as an inland port. The history of Sacavém would revolve around its river, its Roman bridge and its harbor for many centuries.[16]

The first written historical reference to the locality is an ecclesiastical document dated May 1, 1191 (that is, forty-four years after the conquest of Lisbon); it refers to the division of property made by king Sancho I to resolve the frequent disputes between the Bishop of Lisbon, Soeiro Anes, and his chapter. Through this document, the bishop ceded the prebends of the church of São Pedro de Alfama to the chapter, and reserved for himself those of the churches of Sacavém, Frielas, Unhos and Vila Verde dos Francos.

It is known that the Mother Church of Santa Maria de Sacavém was one of the ecclesiastical collegiate churches of the Lisbon District (along with Nossa Senhora do Carvalho de Bucelas, São Julião de Frielas, São João Baptista do Lumiar and São Silvestre de Unhos).[17] For this reason, to this day the official title of the parish priest of Sacavém is prior and not presbyter (commonly known as father).

13th century

From the 13th century there are references to the existence of a sanctuary dedicated to Saint Andrew, associated with a chapel dedicated to the same patron saint, as well as a hospital/shelter, built by Gonçalo Vaz, for the poor (at the time, the several welfare functions were exercised by the same institutions — essentially religious corporations that were united under the same devotion — and thus not only took care of pilgrims, but also of the poor and lepers). Drinking water was supplied both through the Trancão and through a well — the Poço dos Trapos.[17]

The distributions carried out by Alfonso III during his reign show that the existing salt mines in the town belonged to the Order of Santiago.[18]

According to Pinho Leal, during this period, the freguesia would have 900 fires, a number that seems clearly exaggerated for a small town like Sacavém in the Middle Ages.[19]

Even so, the town must have already been an urban center of relative importance in the Lisbon area. A law of Dionisio I,[20] dated 1287, gives an evidence of a general tax applied to the notaries of a significant part of Portugal (excluding the region of Antre Tejo and Odiana and Além-d'Odiana — regulated by a later law —, of the Kingdom of Algarve, as well as other specific places — Braga, Oporto or Alcobaça). Among other towns in the Lisbon diocese (Lisbon, Alenquer, Arruda dos Vinhos, Óbidos, Porto de Mós, Povos, Santarém, Sintra, Torres Novas, Torres Vedras and Vila Nova de Ourém), the parish of Sacavém is mentioned, with a notary, but without knowing the value of the tax (a situation also verified in the case of Alenquer, Arruda, Sintra and Torres Vedras). As in Porto de Mós and Vila Nova de Ourém, where there were two notaries, they paid 45 pounds a year to the crown and it is assumed that the contribution of Sacavém was also the same — although, for example, the council of Povos, in the north of Vila Franca de Xira, with only one notary, paid a value of over 60 pounds; this number, however, was later reduced to 24 pounds a year.[21]

At the end of this century (1288), the prior of the Sacavense parish appears among the names of several religious who ask Pope Nicholas IV for the creation of a studium generale in the city of Lisbon: The names of the abbot of the Monastery of Alcobaça, the priors of the Monastery of Santa Cruz de Coímbra, the Church of São Vicente de Fora, Santa Maria de Guimarães and Santa Maria da Alcáçova de Santarém, as well as the rectors of the churches of São Leonardo de Atouguia (da Baleia), São Julião de Santarém, São Nicolau de Santarém, Santa Iría de Santarém, Santo Estêvão de Santarém, São Clemente de Loulé, Santa Maria de Faro, Santa Maria e São Miguel de Sintra, Santo Estêvão de Alenquer, Santa Maria e São Miguel de Torres Vedras, São Pedro de Torres Vedras, Santa Marinha de Gaia, Santa Maria da Lourinhã, Santa Maria de Vila Viçosa, Santa Maria da Azambuja, Santa Maria de Sacavém, Santa Maria de Estremoz, Santa Maria de Beja, Santa Maria de Mafra and Santa Maria de Mogadouro.

14th century

Sacavém in the patrimony of the Admiralty

After the beginning of the 14th century, by a contract signed on February 1, 1317, Dionysius I commissioned the Genoese Manuel Pessanha to reorganize the Portuguese Navy, giving him the title of Admiral of Portugal as a reward, as well as an annual pension of 3000 pounds "in money of the currency of Portugal", distributed in three payments of equal value to be accrued in the months of January, May and September and taken from the royal revenues of Sacavém (as well as from Unhos, Frielas, Camarate and, later, from September 24, 1319, from that of Algés and also of Odemira). This contract would be successively confirmed in the person of Manuel Pessanha through letters of grant dated February 10 and 23, 1317, April 14, 1321, April 21, 1327, and in that of his son and heir to the admiralty, Lançarote Pessanha, on September 20, 1356, and again in 1368, 1370, 1371 and 1372.[22]

It is understandable that Sacavém was one of the lands donated to Admiral Pessanha, since, at the ecclesiastical level, it had one of the largest prebends of the council and district of Lisbon; In fact, according to a document dated March 25, 1325 — of which we know the transfer made in 1747 by the engineer of the kingdom and keeper of the Torre do Pombo, Manuel da Maia (the rebuilder of the Baixa) and later transcribed by Fortunato de Almedia in his monumental work História da Igreja em Portugal (History of the Church in Portugal) —, the executing judges of the city and council of Lisbon appraised the church of Santa Maria de Sacavém for a value of 650 pounds and "the common of the rationers of it, with respective loans", in 180 pounds, being only appraised in higher value the episcopal table (18.000 pounds) and the capitular table (12,742 pounds) of the bishopric, as well as the Monastery of São Vicente de Fora (1,300 pounds), the convent of the same monastery (1,850) pounds and the Monastery of Odivelas, with the annexed churches of São Julião de Santarém, Santo Estêvão de Alenquer and São Julião de Frielas with the respective vegueria (2.000 pounds) — which proves the wealth of the freguesia of Santa Maria de Sacavém in the Middle Ages; as an example, the neighboring church of São João Baptista do Lumiar paid only 300 pounds, and its rationers 80; that of Loures, another 300; that of Tojal, only 100; that of Santa Maria de Bucelas, 250, and that of São Silvestre de Unhos, 300, with the respective rationers paying 80 pounds.[23]

Sacavém, royal land

Despite the donation to the Admiral, the King continued to maintain his privileges in Sacavém, since it was a realengo territory. On March 13, 1338, in a contract of aforamiento "de huũa courela de vinha na pelaçam, freguesia de freelas", king Alfonso IV alludes to a certain Gonçalo Martinz, "meu scriuam dos meus Regaengos de Sacauem e de ffreelas"; It follows that the realengo of Sacavém and Frielas must have continued to maintain its relative importance within the freguesias of the municipality of Lisbon, as can be deduced from the reference to the existence of two notaries, Afonso Braz (notary of Sacavém) and Gomes Peres (notary of Frielas), in the same document. In two other instruments of purchase and sale of a haystack in Frielas by the king, dated June 17 of the following year, reference is already made to the same Gomes Peres as the only "tabaliom de ffreelas e Sauauem [sic]".[24]

Later, in a letter of donation of the convent of Chelas dated 1347, the figure of the public notary is again alluded to ("Gómez Pérez Tabellíom de Sacauẽ", probably the notary previously cited as being in Frielas), with the latter appearing among the witnesses to said donation.[25] By this time, in addition, the Augustinian monks of the Monastery of Chelas must have owned several urban and rural properties; cultivating vines and olive trees in the latter.

In addition to the royal notary, the royal estate of Frielas-Sacavém also had a royal official responsible for the collection of taxes, which once again demonstrates the importance of this rich royal land: through a document dated August 15, 1312, Dionisio I, wishing to give grace and mercy to the Royal Monastery of Odivelas, founded by himself, grants the possession of a salt mine that belonged to a bailiff of his father (Vicente Pássaro), appointing Silvestre Garcia, his master in Frielas-Sacavém, and Estêvão Vicente, his notary in the same royal estate, to be responsible for this legal business, so that he could then proceed to transfer the property to his new grantee.[26]

From this period we also know the name of the Prior of the Sacavense Church, a certain Petrus Iohannis (vulgarly, perhaps he was known as Pedro Joanes or Pedro Eanes or more probably Pedro Anes), who accumulated the position with the functions of canon of the cathedrals of Braga and Coimbra, his name appears in the description of a pending seal present in a transfer in public form of a search, related to a question about the Lezíria (agricultural area) of Atalaia, in the municipality of Santarém, and included in book 5 of the chancellery of Dionisio I (known as the Libro de las Lezírias). The seal reads: "Sigillum Petri Iohannis Iohannis Bracarensis Colimbriensis canonicj et prioris sancte Marie de Sacauen", or Seal of Pedro Eanes, canon of Bracarensis and Coimbrense and prior of Santa Maria de Sacavém.[27]

At the beginning of the reign of Peter I (1357), the monarch proceeds to the confirmation of several of the privileges of the villas and towns of the kingdom, which dated from previous reigns, finding in this context two different references to the royalty of Sacavém and Frielas in his chancellery. Thus, on September 11 of that year, the monarch confirms and grants "todos seus priujlegios foros liberdades e boons custumes que sempre ouuerom, etc. " (all their privileges, fueros, liberties and good customs that they always possessed) to the councils (that is, to the assembly of good men of the towns or villages gathered in councils) of Besteiros, Covilhã, Guarda, Leiría, Mendiga, Monsaraz, Montalegre, Sacavém and Frielas, Santa Comba Dão, Serpa, Serró Ventoso and Soure, as well as the Monasteries of Alcobaça and Arouca, the Bishopric of Oporto, the Orders of the Hospital and Santiago, the Estudo Geral de Coimbra and the Jewish communities of Coimbra and Beja. In October of the same year, it confirms again the privileges to other localities, and this time it refers only to the "concelho do reguengo de Sacauém" (council of the royal estate of Sacauém), together with the village of Cuba, term of Beja, the councils of Asseiceira and Atalaia, and to the inhabitants of Azeitão.[28]

_-_Lissabon_Museu_Nacional_de_Arte_Antiga_19-10-2010_16-12-61.jpg.webp)

Sacavém in the chronicles of Fernão Lopes

... in the House of the Queens

Still at the end of the 14th century, D. Ferdinand I solemnly donated by means of a letter of arras, to his wife D. Leonor Téllez de Meneses, on the occasion of their marriage in Leça do Balio (1371), the royal estates of Sacavém, Camarate, Frielas, Melres de Riba Douro and Unhos, as well as the villages of Abrantes, Alenquer, Almada, Atouguia da Baleia, Aveiro, Óbidos, Sintra, Torres Vedras and Vila Viçosa, all of which became part of the House of the Queens (according to Fernão Lopes[29]).

... in the Fernandine Wars

Fernão Lopes himself, in the prologue to the same chronicle, alludes to the river of Sacavém, saying that many ships arrived in Lisbon from "(several places)," and that "estavam à carga no rio de Sacavém e à ponta do Montijo, da parte de Ribatejo, sessenta e setenta navios em cada logar, carregando de sal e de vinhos" (they were being loaded in the river of Sacavém and at the point of Montijo, on the part of Ribatejo, sixty-seven ships in each place, carrying salt and wine).[30] In this way, one can intuit the importance that the river port of Sacavém had at that time.

Also in the same chronicle, Fernão Lopes states that, during the third Fernandine war (1381-1382), an English squadron destined to help the Portuguese king in his pretensions to the throne of Castile, anchored in the Tagus along Lisbon; Despite this, its commander the Earl of Cambridge Edmund of Langley (future Duke of York, son of Edward III and brother of John of Gaunt), warned of the eminence of the arrival of a Castilian fleet coming from Seville and commanded by Admiral Fernando Sanchez de Tovar, decided to lead his navy to a safe harbor, having agreed with D. Fernando with him "que era bem que aquela frota e outros navios que hi jaziam, que se fossem todos a Sacavem, que som duas legoas da cidade, e ali se lançassem todos por jazerem seguros" (that it was best that that fleet and other ships that were there should go to Sacavém, which is two leagues from the city and there they should all join together to be safer).[31] The union of the Portuguese and English fleet at the mouth of the Trancão should generate a dissuasive effect on the Castilians, in such a way that effectively "quando chegaram ante a cidade, acharom o mar desembargado de navios, e souberom como todos jaziam em Sacavem; e quando allá forom e virom o rio guardado e as naos estar d'aquela guisa, tornarom-se, e nom acharom em que fazer damno segundo seu desejo, e forom-se pera Sevilha" (when they arrived at the city, they found the sea without ships and knew that all were in Sacavém; and when there they went and saw the river and the ships together, they returned and without finding the way to make an effective damage, they returned to Seville).[31] The English ships were anchored in Sacavém from the end of August until December 13, 1381, when they set course for England again.

... in the crisis of 1383-85

Fernão Lopes again mentions the locality in the Crónica del-rei D. João I, in the context of the crisis of 1383-1385 and the siege that the Castilians imposed on Lisbon in 1384:

"A boat in which Gonçalo Gonçalves Borjas was riding, decided to march towards Restelo, and the contrary wind carried it by force on the road to Sacavém."[32]

Donation to the Holy Constable

Despite belonging to the patrimony of Leonor Téllez, Sacavém was positioned in favor of John I, being as a reward subtracted (along with Unhos, Frielas and Camarate) from the Queen's House, and reintegrated into the civil and criminal jurisdiction of the Lisbon District, on May 4, 1384; on April 7, 1385, one day after his election as King in the Cortes of Coímbra, D. John I handed over the realengos of Sacavém, Camarate, Frielas and Unhos to the Constable of the Kingdom D. Nun'Álvares Pereira, with all its terms, salt mines, and other rights, leaving this patrimony ascribed to the assets of the County of Ourém, to which Nun'Álvares had acceded by grace of the king.

Meanwhile, in May 1393, according to the Crónica do Condestabre de Portugal, the Constable proceeded to a distribution of benefits and lands to the knights who had helped in the war against Castile and in the service of the Master of Avis, ceding their usufruct, although he kept the bare ownership of them. The "ship of Sacavém" was thus given to João Afonso de Alenquer (described as "accountant of his House"[33]), who would later become Minister of Finance of John I and one of the main benefactors of the conquest of Ceuta in 1415.

Through the daughter of the Constable, Beatriz Pereira de Alvim, who would marry D. Afonso, Count of Barcelos, illegitimate son of the new monarch and future Duke of Bragança, this estate would eventually become an honor of the powerful House of Bragança (the present Quinta de São José was also included in the Braganza estate in the 17th century), which also included the freguesias of Apelação, Charneca, Camarate, São João da Talha and Unhos.

In 1387, the village of São João da Talha (until that time called Sacavém Extra-Muros) achieved its autonomy from Sacavém and was also integrated in this noble honor; finally, in 1397, the new freguesia of Santa Maria dos Olivais was separated from Sacavém by the Patriarchate of Lisbon, D. João Anes.

15th century

At the beginning of the 15th century, with the increase of the number of Jews in Portugal, according to studies carried out by several historians, the number of Jewish communities also increased, from about 30 in the 14th century to almost 140 in the 15th century. One of them was located in Sacavém, and the Jewish quarter was built in the vicinity of the town.

Death of Queen Felipa of Lancaster

In the chronicles of Rui de Pina and Duarte Nunes do Leão, there are allusions to Sacavém, the latter affirming that the royal family withdrew to this town when an outbreak of plague began in the capital, in 1415, on the eve of the Conquest of Ceuta. According to these chroniclers, it was in the hermitage of the Martyrs of Sacavém that Queen Philippa of Lancaster died of the plague, just before the embarkation of king John I and his children to Morocco. However, according to Gomes Eanes de Zurara (in the Crónica da Tomada de Ceuta), the royal family would have tried to escape to Odivelas, in order to avoid the plague, thus establishing that the death of the queen would have been in the Monastery of San Dionisio de Odivelas, and not in Sacavém — version that ended up being accepted as the most accurate.

The regency of Pedro the infante

At the end of the 1430s and the beginning of the following decade, due to the disagreements between Leonor of Aragon, the widowed queen (whom Edward I left in charge of the regency of the kingdom), and the infante Pedro, Duke of Coimbra, her brother-in-law, whom some social groups wanted to see at the head of the regency, during the minority of D. Afonso V, the region of Sacavém was the scene of intense diplomatic activity on the part of the co-regents. The Queen Regent established herself together with her children king Alfonso V, Crown Prince Ferdinand and the remaining Infantas in the town at the beginning of August 1439, and there are numerous royal documents signed in the locality; D. Pedro lived between Lisbon (where he maintained his residence) and Sacavém, in order to sign these documents.

This situation continued until the beginning of September, the last letter signed by the two (in the neighboring town of Camarate, where he ended up settling for some time, due to the greater proximity to Sacavém), before the prince Pedro left for his stately palace in Tentúgal. The queen remained in Sacavém until September 25, when she moved to Alenquer; Rui de Pina wrote about this fact that "a Raynha se partió com ElRey e seus filhos e sua Casa pera Alanquer, muyto revosa dos movimentos e alvoroços de Lixboa, e pouco segura em Sacavem onde estaba, por ser Aldea fraca e tam perto da Cidade" (The queen left with the king and his children and his house to Alenquer, far away from the movements and disturbances of Lisbon and not very safe in Sacavém for being a small village near the city).[34]

To resolve the question of the regency, Courts were convened in Lisbon in 1439, in which the three States decided to attribute the regency to the prince. At the beginning of 1440, the Duke of Coimbra spent about a month and a half in Sacavém (February 23 to April 6), as can be seen from several letters signed by him, concerning decisions taken at the Cortes of the previous year.[35]

Sacavém, honor of the House of Bragança

On April 4, 1422, shortly before entering the Convento do Carmo (which he founded years before in Lisbon as Frei Nuno de Santa Maria, O.Carm.), Nun'Álvares Pereira proceeded to a new distribution of his property, having donated the County of Ourém to his grandson Alfonso; in the same document it is also declared that the constable will proceed to the donation of the "boat of Sacavém", with all its rents and rights to a certain Gil Airas, his notary. The execution of the will of Nun'Álvares, who died in 1431, conferring the royal estate and the ship of Sacavém to his grandson D. Alfonso was confirmed by King Edward I through a letter dated November 24, 1434.

With the death of Count Alfonso in 1460, without legitimate children, his estate passed to his father, D. Alfonso, Duke of Bragança, who, dying after a few months (1461), would bequeath to his youngest son, D. Fernando, Count of Arraiolos and future Duke of Bragança, the possession of that territory. The new head of the House of Bragança thus gathered, once again, the wealth acquired by Nuno Álvares Pereira after the beginning of John I' reign.

As part of the Braganza patrimony, Sacavém experienced times of greatness (but also of misfortune) as the history of this dynasty unfolded. Thus, when the third Duke was executed, D. Fernando II was executed in Évora (June 20, 1483), and his property subsequently confiscated, the honor of Sacavém returned to the Crown as a royal estate (a royal charter of July 28, 1483, signed by John II in Setúbal, gave a certain João da Guerra a quarter of the fruits, tithes and fish of the royal estates confiscated from the Duke of Sacavém, Unhos, Camarate, Frielas and Charneca).

When D. Manuel I ascended to the throne in 1495, he restored the House of Bragança and returned to it the assets it had once held, including, of course, the honor of Sacavém. Until the end of the monarchy in 1910, the Duke of Bragança (and, from 1640, the King of Portugal) would be the lord of Sacavém and in that condition would hold several privileges, such as the tolls for crossing the river as well as the village taxes.

Another indirect reference to the town is found in a request from the procurators of the Chamber of Lisbon to the Cortes of Leiria in 1348, according to a document in the famous Libro dos Pregos (Book of Requests), according to which it was requested that the river ports of the Tagus (including Sacavém), where the transport of goods had long been carried out, should be cleaned to prevent them from losing draught.

Modern Age

16th century

Period of unsurpassed development

During this period, Sacavém saw its urban area expand, both in the direction of Olivais (through Rua Direita, now Rua Almirante Reis, oriented towards Lisbon), and in the direction of the Tagus and Trancão, through Rua dos Mastros (now Rua José Luís de Morais), which also served to connect Sacavém de Cima and de Baixo, and led to the bridge that joined the two banks of the river. In essence, the fundamental road connections remained practically unchanged until the middle of the 20th century.

Through the two rivers, the Tagus and the Trancão, passed a large part of the commercial activity of Sacavém; the Trancão was in fact the main route for the exploitation of the products of the saloia area in the Lisbon area, being full of boats until the Lisbon Earthquake took place. On the banks of the Trancão, where there was already a river port with docking quays, a naval shipyard was set up during the period of the discoveries, where shipyards, not only merchant ships but also warships, were built, keeled and repaired.[16] Both the port and the shipyard were active until the 18th century, having contributed intensely to the economic importance of Sacavém, in parallel with the production of the most varied horticultural and fruit species of its farms, praised in several accounts and which, throughout two centuries, allowed the supply of Lisbon with fresh produce from the land.

In fact, although Sacavém had lived largely at the expense of its river, no less important was the role that agricultural activity played in the economy: from a letter dated January 26, 1501, we know that the royal estate of Sacavém produced wheat and barley in equal proportion.[36]

References to Sacavém during the Golden Age

From the previous year (1500), an important reference to Sacavém and its tax collector is known, in the Carta do Achamento do Brasil (Letter of the Discovery of Brazil), by Pêro Vaz de Caminha ("Passou-se então para a outra banda do rio Diogo Dias, almoxarife que foi de Sacavém, o qual é homem gracioso e de prazer"). (I pass then to the other side of the river Diogo Dias, tax collector of Sacavém, who is a man of grace and pleasure). It is presumed that this Diogo Dias was the brother of the navigator Bartolomeu Dias, and that he himself was responsible for the discovery of the island of Madagascar.

In 1511, the population of Camarate, in frank economic and demographic growth, was separated from Sacavém through a charter granted by Manuel I on May 1 of that year, significantly reducing the geographical dimension of the parent freguesia by half.

Between 1531 and 1533, during the visit to the Cistercian monasteries in the Iberian Peninsula (in an attempt to moralize the monastic life of the peninsular monks), carried out by the Abbot of Clairvaux Edme de Saulieu, an allusion to Sacavém and its ship appears in the work Peregrinatio Hispanica, written by the also Cistercian Claude de Bronseval, saying in his account, on August 12, 1532, that "exiuit Dominus Vlixbonam et uenit transire barquam a Sacauent et iacere in burgo uocato Poue" (Monsignor left Lisbon and crossed the boat of Sacavém and rested in the burgh called Póvoa [of Santa Iría]).[37]

In 1535, Diogo Botelho Pereira arrived in Lisbon, who had committed the heroic feat of traveling alone from India to Portugal in a simple fusta (a very small boat) rigged by himself, in order to tell the sovereign (who was then in Évora) that the construction of the fortress of Diu had begun under the auspices of the governor in India, Nuno da Cunha. According to Diogo do Couto, in his work Décadas de Ásia, as Diogo Botelho did not bring letters from the governor confirming his story, the king did not want to believe it but set out for Lisbon to see the ship that had been used for such an undertaking. According to Couto, the whip was taken to the mainland, in Sacavém, and remained there for several years (until it fell to pieces) to be visited by the people who did not believe Botelho's deed; for this reason, Gaspar Correia, in his work Lendas da Índia, reports that the king ordered the boat to be burned so that "não se vulgarizasse a ideia de que era possível fazer a viagem em tão modesto meio" (the idea that it was possible to make the trip in such a modest method would not be vulgarized).

A document is preserved dating from the middle of the reign of John III, which appeared in the royal chancellery, according to which the monarch donated the yield of several localities around Lisbon (Amêndoa, Abrantes, Aldeia Galega da Merceana, Aldeia Galega do Ribatejo, Alhandra, Alhos Vedros, Almada, Alverca, Azeitão, Barcarena, Barreiro, Benfica, Carnide, Cascais, Castanheira, Cheleiros, Coina, Colares, Ericeira, Lavradio, Lumiar, Mafra, Palhais, Ponte de Sor, Povos, Punhete, Sacavém, Santo António do Tojal, Sardoal, Sesimbra, Sintra, Talha, Torrão, Vialonga and Vila Franca), constituting a royal monopoly, to the nuns of the Monastery of Santa Clara in the capital.[38]

In the Tratado da Majestade, Grandeza e Abastança da Cidade de Lisboa: estatística de Lisboa of 1552, composed by João Brandão de Buarcos, there are reports of 1300 trading boats around Lisbon, 120 of which were owned by the inhabitants of Sacavém, Camarate, Unhos, Frielas, Tojal and Povos.

The Regimiento de los Oficiales Mecánicos de la Muy Noble y Siempre Leal Ciudad de Lisboa, composed in 1572, ordered that no boat passing through the river of Sacavém could carry more than eight people simultaneously, and also established that the boat could not carry "Moors, Indians, blacks or mulattoes", regardless of whether they were slaves or free men.

The difficult years of the 16th century: the succession crisis

In the last quarter of the 16th century, the prolific activity continued in Sacavém, where Miguel de Moura owned a farm. Miguel de Moura was the scribe of King Sebastian I, as well as a member of the council of governors of the kingdom in the time of Philip III. He was also one of the patrons of the Convent of Our Lady of the Martyrs and of the Conception, of the order of the Poor Clares, founded by him and his wife Brites da Costa, where she would live after her widowhood.

After the death of Cardinal Henry I, a council of governors of the kingdom of Portugal, appointed by him, assumes power; the population, wishing not to see the national crown united to Spain, acclaims in Santarém, on July 19, the Prior of Crato D. Antonio as king. On the 21st, accompanied by five hundred men on foot and horseback, he set out for the capital, arriving on the 23rd at Sacavém, at the gates of Lisbon, and was received with great enthusiasm. In spite of it, "à passagem do cortejo por Sacavém sucedia o primeiro episóido dramático do seu reinado: um tiro desgarrado, que alguns supunham ser dirigido contra o próprio monarca, foi atingir em cheio o fidalgo D. Francisco de Almeida, que caiu redondamente no chão"[39] (as the cortege passed through Sacavém, the first dramatic episode of his reign occurred: a torn shot, which some suppose to be directed against the monarch himself, was aimed squarely at the nobleman Francisco de Almeida, who fell roundly to the ground).

During that time, when the integration of the Kingdom of Portugal into the Crown of Spain was underway, the potential of Sacavém and its port did not go unnoticed by one of the main Castilian military men sent to Lisbon, Admiral Álvaro de Bazán, Marquis of Santa Cruz de Mudela, who, in a letter to King Philip II of Spain (preserved in the War and Navy Section of the General Archive of Simancas), states that:

«[...] It is not convenient to have the ships in this river of Lisbon because they get damaged and spend more moorings with the stormy weather that other ships win and it would be better to have them in the river of Sacaven, which is two leagues from this city where with two ropes of esparto grass and two men they would be safe and without being damaged, nor with risk of getting lost for not entering there sea that could harm them and have much shelter that the ships they use for being so large cannot enter said river nor would they fail to enter the ports of the Indies and make navigation more in order to be there the summer to negotiate and dispatch without risk. [...]».[40]

After the battle of Alcántara, held near the town of the same name, in the suburbs of Lisbon, on August 25, 1580, the Prior do Crato, defeated by the forces of the Duke of Alba, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, was seriously wounded but decided to lead the resistance in the north of the country, leaving Lisbon for Santarém, the town that first acclaimed his royalty. Although the exact itinerary of the escape is not known, Joaquim Veríssimo Serrão suggests that, in escaping from Lisbon, D. António would have passed through either Sacavém or Tojal, two freguesias bathed by the Trancão River and where there were bridges leading to Vila Franca de Xira, where he would take the Azambuja road to Santarém.[41]

The great plague epidemic of 1599

At the end of the century (1599), during a great plague epidemic, the statue of Our Lady of Health was discovered, and from then on it was venerated with special affection by the people of Sacavém and placed in the Chapel of St. Andrew, which became known as the Chapel of Our Lady of Health and St. Andrew.

17th century

Ruin of the Roman bridge

Meanwhile, with the ruin of the Roman bridge (still referred to in 1570), without ever having been rebuilt, due to the negligence of the rulers, the crossing of people and goods across the river of Sacavém had to be done arduously by boat; the Duke of Bragança, donator of the town and its rights, rented the toll to the boatmen of Trancão in exchange for 300 thousand reais per year. Initially, each gentleman paid 3 reais in tolls; later, the Duke decided to increase the value of the tax, charging 5 reais for pedestrians (who until then were exempt), 20 reais for horsemen and draught animals and 40 reais for the transport of carriages. These exaggerated prices led the monarch (then Philip III of Portugal) to compare it with the rates set for the crossing of other waterways, concluding that they were too onerous for the inhabitants of the region. Therefore a regiment was issued (dated May 25, 1628) that sought to favor the populations, returning to the value of the 3 reals toll, applied to all individuals.

As an alternative, many people preferred to move a little further, towards Tojal and there cross the Trancão through a bridge in better condition.

Sacavém in the choreographies of the 16th century

In 1620, Fray Nicolau de Oliveira, in his work Libro das Grandezas de Lisboa alludes to Sacavém in this way: "Passando o rio, ficam da parte de Lisboa as freguesias seguintes: Sacavém, onde há um mosteiro de religiosas franciscanas capuchas descalças, em número de trinta, sem terem servidoras; todas servem nas tarefas comuns do convento. Este lugar tem uma freguesia, com duzentos e sessenta fogos, e setecentas pessoas"[42] (Passing the river, the following freguesias remain on the Lisbon side: Sacavém where there is a monastery of Franciscan Capuchin discalced nuns, in number of thirty, without having servants; all serve in the common tasks of the convent. This place has a freguesia, with two hundred and sixty fires and seven hundred people).

Years later, in 1629, Miguel Leitão de Andrada prints in his work Miscelânea the apparition of the image of Our Lady of Light of Pedrógão Grande, with many curiosities and diverse poetries, in which he alludes succinctly, in a lively and curious register, then in the first pages of his "2nd. Dialogue" (maintained between the characters Galácio and Devoto), to the boat of Trancão (talking about the previously mentioned payment of the toll to use the bridge), to the bridge of Sacavém (then in ruins, lamenting the negligence of the Lisbon chamber), to the port where the ships docked, to the convent of Our Lady of the Martyrs and to the Battle of the Sacavém River:

Second Dialogue

The reason for the Monastery of Our Lady of the Martyrs of Sacavém is given. And of the stone bridge that there was and could be there now. [...]

Galácio: Since we have come this far walking through all that honorable place of the Convent of Our Lady of the Light, let's keep up the pace, since it seems that this boat of Sacavém is moving unmoored.

Devoto: Oh, of the boat!

Galácio: Patience, we have to wait for it to turn.

Devoto: This is one thing that I miss, that Lisbon should be held back by this boat, so much against its nobility and the comfort of its inhabitants and travelers, since there could so easily be a bridge of boats here as in Seville, at little or no cost.

Galácio: There must be something in that in between, for if it is not done, being notoriously so necessary and useful.

Devoto: None that I know of, if it were not for not harming the income that the Duke of Braganza obtains from this boat, which is leased to him at three hundred thousand reales each year, having seen it many who are alive today, being leased at ten or twelve thousand reales each year, and paying three reales for each person and horse now to come, because of the great neglect of the Chamber of Lisbon.

Galácio: It does not seem that it should be because of what you say about the Duke, who, being such a great prince, should not consider such trifles in regard to the common good and greatness of Lisbon, which, if it were asked of him, would very easily enlarge this boat.

Devoto: If this is not so, it must be less so what they say, that because of the ships to which this river gives shelter, because besides the fact that it is no longer given here, but on the shore there; it was easy to open that bridge, and past the ship to close it, or to make it where the ships could not give them those blows by the side of the sea. Nor less should the passage of the ships, which sail up the river, which could pull the counterweights and pass, how much more, that those of this river are so small, that with them they could pass under the same bridge; for which reason the duke's reason seems to me considerable if any or cause or impediment, and may that have easier remedy. With that means they call water, again imposed for the bringing of water to the dew, in each cuartillo of wine and real in each piece of meat, the duke could be satisfied and a bridge of boats could be made here.

Galácio: In spite of everything, it seems to me too costly to have to support that bridge, in addition to the size of it.

Devoto: It would not be if not too little; for what are six or seven boats, which can last thirty or forty years? When more than just the horses at three reales would suffice well at that cost, because the cattle will also come to that pass.

Galácio: There would also be difficulties and complaints about that payment.

Devoto: If that does not happen on the boat, it would be even less so on the bridge; when, in addition, a gate could be placed at the entrance, and the inconvenience would cease. And I say this in case the city should not be able to support by grace, what was the great nobility of Lisbon, to which one should first turn, rather than to other things less necessary and less noble. For we see that when Lisbon was nothing, in comparison with what it is today, it had here a stone can, as now seems to be appreciated from the pieces of pillars that you see of it, on this bank and on the other.

Galácio: That would be many thousands of years ago, in times when this river would have been narrower and shallower.

Devoto: The width is the same, as shown by the vestiges of the pillars that you see, that the river reaches them and does not pass; and as for the depth, even if it is more, which we do not know, it could well be remade from loss, that at the bottom must be the baces of the pillars; above all, that the art of architecture with much money reaches and can, to make it of a single arch: for they say, that this art is infinite without end. And we see that in that so famous river Danube, there is still standing the bridge that the emperor Trajan had made, with almost all the internal pillars above the water one hundred and fifty feet, the twenty of them, which are similar, and each one sixty feet thick, and the span of each arch one hundred and sixty feet [...] Therefore it was worthy of the greatness of Lisbon, to have here a famous bridge of pier, even if the whole kingdom was spent for it.

Galácio: We would be content with a bridge of boats.

Devoto: And that is what I am treating you about. Regarding what you said about whether this river could have been widened, which was not done here, I know well that the rivers eat and lower the land, and I believe that these large and small valleys and these spacious plains were caused by the waters of the rivers and flooded by them, and by the rains, which eat and carry the land and uncover those bones that the sun was creating and carrying the land from itself. [...] Besides here there are not those thousands of years, that you take care of there was this bridge: because in times in which king don Alfonso Henriques, first of Portugal, surrounded Lisbon and took it to the Moors, being on it he had notice of how the Moors of the region of Alenquer were coming to help it. And knowing that they had to pass by this bridge of Sacavém, he ordered them to take the passage with horse people (which could not be many), to which, finding the Moors, who almost all had passed it, they had with them a very dangerous and unequal battle, because being very few and the Moors many, they could not be excused without being lost, and from them there was a very significant victory in this plane. Where they said later the Moors saw a woman who blinded them and thwarted them, which was the Virgin Our Lady, to whose honor and in memory of this victory was built that church that you see there. Which these years Miguel de Moura rebuilt, who was one of the five governors that King Philip, first of this kingdom, left in it, founded there that very religious monastery of Capuchins. And this church of Our Lady of the Martyrs, for the knights who were buried there, who were killed here in this battle fighting; like the church of Our Lady of the Martyrs of Lisbon, which the English founded in this siege [...] to bury their dead. [...]

Galácio: By that tale many hundreds of years must not have passed, that here there was this can, for that siege and the taking of Lisbon was in the year of 1147, as seen in the signs that are in the Cathedral of Lisbon and the chroniclers all say so, and father fray Bernardo de Brito, after them; and if that bridge in that year was intact that one passed through it as of that battle and past of the Moors and of the ancient tradition and memories, that you say there are in this church; and not having then to be finished, andes to last many years, or hundreds of years that lasted that bridge, and there was it here. Where I consider three things: first, the force of time in spending and consuming everything up to the memory of what was. It is that even the stones also have their age, because we see finished without any memory, no trace, so many things and so big, we know that there were buildings and cities. And how quickly the memory of everything is gone, and how that of that bridge, of which there seems to be nothing else, if not what you tell me with these pieces that we see of it, because of our ordinary pasts of that time, buried great things in oblivion, content with only the present honor of doing them. [...].[43]

Sacavém and the restoration of Independence

According to the Dicionário Histórico, Corográfico, Heráldico, Biográfico, Bibliográfico, Numismático e Artístico de Portugal, the name of the town is mentioned in a coded letter of one of the conspirators of 1640, Dr. João Pinto Ribeiro, which he addressed to the Duke of Bragança John IV, having decided on November 25 that the revolt should take place six days from now, João Pinto Ribeiro was asked to communicate the fact to the future Portuguese monarch, writing to him that it would be the following December 1st, stating "que se devia de resolver o caso dos freires de Sacavém" — (that the case of the monks of Sacavém should be resolved), a locality which was, as has already been said, one of the honors of the House of Bragança, and where the Convent of Our Lady of the Martyrs and of the Conception was located, founded by Miguel de Moura and his wife Brites da Costa at the end of the previous century, and to which the Duke had exempted from the payment of certain obligations; such an allusion to the case of the monks of Sacavém presupposes that there was, perhaps, some dispute between the monastery and the Duke of Bragança, most probably over fiscal obligations. It was through this coded message that the duke was alerted to the need to update the economic contributions to contribute to the Independence of Portugal.[44]

After the Restoration of Independence, the idea arose (especially during the reigns of John IV and Alfonso VI, during the war against Spain) of joining the Trancão River with the Atlantic Ocean, making it flow into the beach of Baleal, thus creating a watercourse from Sacavém to Peniche that would constitute a natural line of defense for the capital; The project was never carried out and gradually faded away, although the idea was revived when, at the beginning of the 19th century, the Lines of Torres Vedras were formed to stop the French invaders.

From the last quarter of this century, according to Joaquim Veríssimo Serrão in his work História de Portugal, there is news of a growing lack of fish not only in the Tagus Estuary, but also in its tributary rivers, including the Trancão River. This lack of fish was due to the massive use of very fine fishing nets (the chinchorros), which led the Lisbon authorities to invoke a municipal regulation of 1591 prohibiting the use of chinchorros; although fishermen rioted against those responsible for urban supply in 1687, the prohibition was maintained.

In 1690, during the reign of Peter II, the sovereign partially financed the reconstruction of the Church of Nossa Senhora da Vitória, half-financed by José Galvão de Lacerda (future chancellor of the kingdom, during the reign of his son John V), and also counting on the contribution of the popular masses.

18th century

In the 18th century, large bullfights were held in Sacavém during the month of September as a tribute to Saint Anne. This is the subject of a curious document preserved in the National Library of Portugal entitled Festas de Sacavem em obsequio da Senhora Sta. Anna: descripção dellas em o terceiro dia em que forão os Cavalleiros combatentes Francisco de Mattos e Jozé Roquete (Sacavém Festivities in honor of the Lady Saint Anne: description of them on the third day when the fighting knights Francisco de Mattos and Jozé Roquete went), whose authorship is attributed to Tomás Galo.[45]

In the first half of the 18th century, the towers of the National Palace of Mafra crossed the Trancão River in boats to Tojal, from where they would be transported by land to their final destination.

By order of John V, the mathematician Bento de Moura (1706-1776) was commissioned to reformulate the Trancão boat, according to Father João Baptista de Castro in his geography work Mappa de Portugal Antigo, e Moderno (1763). This fact caused Pinho Leal to write that a bridge of boats had been built, supposedly before the best known bridge of boats in the country, the one that linked Oporto to Gaia. However, it seems to be a mistake in Pinho Leal's interpretation, as there was never a bridge of boats in Sacavém, since what de Castro writes in two points of his work is: "Por ordem de D. João V se reformou a barca de passagem deste rio pela admirável idéa do nosso insigne maquinista Bento de Moura, com grande commodidade para os passageiros" (By order of John V the passenger boat of this river was reformed by the admirable idea of our insigne maquinista Bento de Moura with great comfort for the passengers) and "existe hoje uma barca de carreira, que por invenção engenhosa de Bento de Moura, facilita muito a passagem de huma para outra parte" (there is today a racing boat, which by ingenious invention of Bento de Moura, greatly facilitates the transfers from one part to the other).

Illustrious Sacavenenses

Also according to Pinho Leal, on December 16, 1741, died in Sacavém one of the longest-lived women in the history of Portugal — a certain Ana da Silva, from Santa Maria dos Olivais, where she was born in January 1626 (being, therefore, 115 years old on the date of her death). This lady, according to a 19th-century scholar, had been married twice and had left a significant offspring, without ever having undergone bloodletting or purging (which, ironically, may well explain her longevity, at a time when medical care was, in most cases, a major cause of death). During the last twenty-five years of his life, he served the poor and sick in the hospital of Sacavém, also participating in a pilgrimage to the sanctuary of the Lord of the Stone in the north of the country, when she was 113 years old. She seems to have preserved such a good memory that, near her death, she still remembered with great accuracy and thoroughness the events that took place in Lisbon on December 15, 1640, with the proclamation of John IV.

In Sacavém, on September 7, 1754, Luís António Furtado de Castro do Rio de Mendonça e Faro, the Count of Barbacena, was born, who would become governor of Minas Gerais, owning a manor property in the town that, from the nineteenth century onwards, would become known as Quinta do Rio; Due to the fact that his heir, Francisco, sided with Miguel I, the title was not revalidated and the Quinta do Rio, with its chapel dedicated to San Roque, ended up falling into ruins.

The Counts of Alvor also had a quinta in the area, but the title ended up in the hands of the Spaniard D.Diego Canalejo de Ulía, in 1759 due to the Távora affair since the count was a cousin of the Marquis of Távora. Today the title is owned by Mr. Rafael J. Canalejo, a Spanish businessman, descendant of the house of Seville, who holds the title on an honorary basis.

The Earthquake of 1755

Sacavém, which after the loss of Camarate in 1511, saw a considerable part of its territory amputated, did not stop growing in terms of population; only occasional decreases were registered, due to the plague (1599) and the Earthquake of 1755, which left it practically destroyed. The primitive main church of Santa Maria, located in Largo da Saúde, was completely demolished (without being rebuilt, passing the main church, over a century, to the Church of Nossa Senhora da Victória, also badly affected); the last vestiges of the Roman bridge over the Trancão also disappeared with the earthquake.

To solve the urban planning problems of the capital and to prevent such a large mortality in the event of an earthquake, the chief engineer of the kingdom, Manuel da Maia, envisaged a solution, including Sacavém and its river valley, in the Terceira parte da Dissertação sobre a renovação de Lisboa (third part of the dissertation on the renovation of Lisbon):

"8th - To this consideration of preserving the streets of Lisbon free from the encumbrances that make them filthy, in which the greater width of the streets and lesser height of the buildings, not exceeding two stories above the stores, will participate, follows necessarily another not less important, and consists in determining a better place in which the said encumbrances may be thrown with less inconvenience; and because one occurs to me more free from them than those already observed, and promises great convenience to the public good, to present such a plan in this place. It consists in that such hindrances are to be thrown into the River of Sacavém, so that with these remains a valley will be formed in it in imitation of that of Chelas, in which the salty waters will reach in time the temple of the Virgin of Vestales, today the convent of the nuns of St. Augustine; for if this small valley so pleasantly succors the court with its vegetables and fruits, when better will the Valley of Sacavém with its many times greater grandeur, and without being able to say that the hindrances thrown there can cause any impediment at the outlet, as can be feared from any of the other ways in which they are thrown from the land: may this consideration have against itself the filling up of the shelter of the vessels in time when they are collected to seek it; but to that may be said that neither do the vessels need the whole river for shelter, nor would it be just that they should be prevented from shelter, but that only that be formed in valley which does not impede it, and which will always be of very profitable greatness."[46]

After the earthquake, following the reports of the evaluation boards sent by Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (future Count of Oeiras and Marquis of Pombal), then Secretary of State of the Kingdom, to all the freguesias of the country (1757), to know the damage caused by the earthquake and which had as a response the famous memórias paroquiais, it can be affirmed the existence of 353 fires. According to these same parochial memoirs, one can also observe the relative size of the port of Sacavém in the context of the river ports of the Tagus: the prior of Sacavém mentions the existence of three docks: the Nossa Senhora, the Barca and the Peixe. However, the importance of this port went into decline; throughout the second half of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, the Trancão, which until then was navigable up to Tojal, began to silt up in an inexorable phenomenon that since then has prevented, until today, navigation in it. In fact, it became a "dead port", according to the expression used by the French naturalist Théodore Monod, in a study entitled L'île d'Arguin (Mauritanie). Essaie historique,[47] devoted to the former Portuguese factory on the island of Arguin, today in Mauritania, where he states that the port that served the Portuguese fortress on the Maghreb coast was as calm as the port of Sacavém....

The policy of industrial and commercial promotion followed by Pombal, leading to the creation of new industries in the kingdom, led the government to subsidize a loan of 6,480 cuentos de real to a certain William Macormick, to set up a textile factory in Sacavém — a factory that was very famous throughout the 19th century.

Bocage and the beaches of Sacavém

At the end of the 18th century, Sacavém merited a reference in the sonnet of Bocage, who was not entirely indifferent to the beauty of the locality:

«Praias de Sacavém, que Lemnoria,

Orna c'os pés nevados e mimosos,Gotejantes penedos cavernosos,Que do Tejo cobris a margem fria.De vós me desarreiga a tiraniaDos ásperos Destinos poderosos,Que não querem que eu logre os amorososOlhos, aonde jaz minha alegria.Oh funesto, oh penoso apartamento!Objecto encantador de meus gemidos,A sorte o manda assim, de ti me ausento.Mas inda lá de longe os meus gemidosGuiados por Amor, cortando o Vento,Virão, ninfa querida, a teus ouvidos.»

Beaches of Sacavém, that Lemnoria,Adorns with snowy and cuddly feet,Dripping cavernous crags,That of the Tagus you cover the cold margin.From you I am uprooted by the tyrannyOf the harsh powerful Fates,That do not want me to attain the lovingEyes, where my joy lies.O dismal, O pitiful apartment!Lovely object of my groans,Fate so commands, from thee I absent myself.But going there from afar my groansGuided by Love, cutting the Wind,Shall go, dear nymph, to thine ears.

Contemporary Age

19th century

Peninsular War and Liberal Wars

In the 19th century Sacavém gained importance due to the constant geo-demographic growth of Lisbon.

During the first French invasion, the commander of the French army, Junot, passed through Sacavém on November 29, 1807, coming from Santarém and heading for Lisbon (upon arriving in Belém, he could see the Portuguese embarkations heading for Brazil where the court would be established until 1821). It was in Sacavém where Junot would receive a Portuguese legation composed of members of the regency of the kingdom appointed by Prince John, individual members linked to Freemasonry as well as members of the Academy of Sciences of Lisbon — among them, men like Francisco de Borja Garção Stockler (future Baron da Vila da Praia) and Luís António Furtado de Castro do Rio de Mendonça e Faro (the Viscount of Barbacena), a native of the town.

After the end of the war, the urgency to fortify the capital of the kingdom was palpable. Therefore , works began on the Estrada Militar (military road), linking Benfica to Sacavém and, later, the construction of the Forte de Sacavém (Fort of Sacavém), on the site where a rough fort used to stand within the Linhas de Torres Vedras, and where today the Direcção-Geral dos Edifícios e Monumentos Nacionais (DGEMN) (General Directorate of National Buildings and Monuments) is located.

On October 2, 1820, the Provisional Board of the Supreme Government of the Kingdom, initially formed in Oporto in the wake of the liberal Revolution of Porto on August 25, 1820, with the aim of governing the country and convening constituent courts, passed through Sacavém in procession to the Rossio Square in the capital, and was joined in Alcobaça with another provisional board formed in Lisbon on September 15, after the escape of the governors of the kingdom. In this procession participated illustrious figures of the liberal movement as Manuel Fernandes Tomás, Manuel Borges Carneiro, José Ferreira Borges or José da Silva Carvalho, all of them prominent members of the sinedrio, secret organization that fought for the institution of a constitutional regime in Portugal.

The 23rd Infantry Regiment also passed through the town, destined to protect the Beira border against the attacks of the reactionary insurrectionary forces supported by Spain, which toasted Miguel I as absolute king in the neighboring town of Vila Franca de Xira — in a process known as the Vilafrancada.

Finally, on October 12, 1833, part of the forces of Miguel I, after being expelled from Lisbon by the Duke of Saldanha and defeated in a brief encounter near Loures, went to Sacavém, in order to take the road to Santarém, towards where they were fleeing; after crossing the Trancão, they set fire to the wooden bridge that connected the two banks and that had been rebuilt shortly after the earthquake of 1755. Only in 1842 would a new bridge be built, this time in stone and iron. A lithograph of this bridge, by Tomás José da Anunciação, dated 1850, can be consulted at the National Library of Portugal.

Industrialization and progress

Likewise, this geographical location in the suburbs of Lisbon inevitably led to the tertiarization of the town. Countless industries were installed in the region, such as the dye factory at Quinta das Penicheiras, or the famous Fábrica de Lozas de Sacavém, founded in 1856 (operating uninterruptedly until 1983). Names inseparable from the history of Sacavém are linked to it, such as John Stott Howorth (the Baron of Sacavém), James Gilman and Herbert Gilbert. It was thanks to it and its tiles that Sacavém became known in Portugal and in a large part of the world, leaving in the historical memory the phrase: "Sacavém is another tile!".

In 1852, Sacavém became part of the newly created municipality of Olivais. The new municipal executive had to deal with the problems of a vast council, in a time of great economic, social and legal changes, and it is not surprising, therefore, that among the vast correspondence exchanged, there is a request from the parish council of Sacavém, asking the chamber to appoint a guard to watch over the cemetery of the town, because it was "'devassado e profanado por animais em consequência de se não achar devidamente preparado" (devastated and profaned by animals as a result of not being properly prepared), a fact that led to the situation that, in violation of the laws approved a few years earlier regarding burials in cemeteries, people continued "n'aquela paróquia, com detrimento da saúde pública" (in that parish, to the detriment of public health), burying the deceased in the churches.[48]

On October 28, 1856, the initial section of the northern railway line was inaugurated, between Lisbon and Carregado, passing through Sacavém and crossing its river, by using a bridge built in England and later transferred to Portugal. Even before that, the first experimental trip, carried out on July 8, 1854, took place between Sacavém and Vila Franca.

The future first Marquise of Rio Maior (Maria Isabel de Lemos), who was only fifteen years old at the time, wrote in her diary a reference to the inauguration and to the (not very honorable) passage of the train through the town — in fact, the locomotive was losing wagons along the way:

"Some, of guests, in Olivais. the "wagon" of the Cardinal-Patriarch, and of the Cabildo, remained in Sacavém; one more, full of dignitaries, stopped in Póvoa [...]."[49]

Eça de Queirós also mentions the town and its railway station in his work Correspondência de Fradique Mendes, thus continuing to demonstrate the importance that in the mid-19th century the Trancão held for the local population:

"We arrived at a station they call Sacavém — and all that my eyes full of sleep saw of my country, through the humid crystals of the wagon, was a dense fog, from where dying little remote and vague lights emerged here and there. They were lanterns of faluas sleeping in the river [...]."

The development of oyster cultivation in the Tagus Estuary in the 19th century led to the demarcation of areas for the exploitation of this natural resource; by a law of the ministry of the Marquis of Sá Bandeira, on September 9, 1868 (confirmed by two regulations of the government of the Duke of Loulé on November 10, 1869, and January 26, 1870, respectively), the entire river bank from Vila Franca de Xira to Olivais, also including parts of Alhandra and Póvoa, but excluding the mouth of the Trancão, were established as oyster cultivation areas on the north bank of the river. By the end of the century, due to material deposits, the practice had been largely abandoned.

In the meanwhile, the industrial development led to a great demographic and urban growth. The population increased a lot in half a century (working more than half only in the tiles factory), and Sacavém gained new contours; the old ruined farms were giving place to working villages. Parallel to the earthenware factory, many other industries were created in the region, especially the transformation of cork, textile, chemical dyes and foodstuffs, and in the 20th century, hygiene products.