The history of human activity on Santa Catalina Island, California begins with the Native Americans who called the island Pimugna or Pimu and referred to themselves as Pimugnans or Pimuvit. The first Europeans to arrive on Catalina claimed it for the Spanish Empire. Over the years, territorial claims to the island transferred to Mexico and then to the United States. During this time, the island was sporadically used for smuggling, otter hunting, and gold-digging. Catalina was successfully developed into a tourist destination by chewing gum magnate William Wrigley, Jr. beginning in the 1920s, with most of the activity centered around the only incorporated city of Avalon, California. Since the 1970s, most of the island has been administered by the Catalina Island Conservancy.

Pre-European settlement

Prior to the modern era, the island was inhabited by people of the Gabrielino/Tongva tribe, who, having had villages near present-day San Pedro and Playa del Rey, regularly traveled back and forth to Catalina for trade. The Tongva called the island Pimu or Pimugna and referred to themselves as the Pimuvit or Pimugnans.[1] Archeological evidence shows Pimugnan settlement beginning in 7000 BCE. The Pimugnans had settlements all over the island at one time or another, with their biggest villages being at the Isthmus and at present-day Avalon, Shark/Little Harbor, and Emerald Bay.[2] The Pimugnans were renowned for their mining, working and trade of soapstone which was found in great quantities and varieties on the island. This material was in great demand to make stone vessels for cooking and was traded along the California coast.[3][4]

Archaeologists have learned much about these tribes from middens, ancient dumps where they tossed everything they no longer needed. These middens can today be identified by mounds of crumbled abalone shells. It is estimated that there are over 2,000 middens on Catalina Island, only half of which have been discovered. Evidence from these middens indicate that around 2000 BCE as many as 2,500 lived on Catalina Island.[5]

European explorers

The first European to set foot on the island was the Portuguese explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, who sailed in the name of the Spanish crown.[6] On October 7, 1542, he claimed the island for Spain and christened it San Salvador after his ship (Catalina has also been identified as one of the many possible burial sites for Cabrillo). Over half a century later, another Spanish explorer, Sebastián Vizcaíno, rediscovered the island on the eve of Saint Catherine's day (November 24) in 1602. Vizcaino renamed the island in the saint's honor.[2]

The colonization of California by the Spanish coincided with the decline of the Pimugnans. They suffered from the introduction of new diseases to which they had little immunity and the disruption of their trade and social networks caused by the establishment of the California missions. By the 1830s, the island's entire native population were either dead or had migrated to the mainland to work in the missions or as ranch hands for the many private landowners.[2]

Franciscan friars considered building a mission there, but abandoned the idea because of the lack of fresh water on the island. While Spain maintained its claim on Catalina Island, foreigners were forbidden to trade with colonies. However, it lacked the ships to enforce this prohibition, and the island served as home or base of operation for many visitors. Hunters from the Aleutian Islands, Russia, and America set up camps on Santa Catalina and the surrounding Channel Islands to hunt otters and seals around the island for their pelts. The pelts were then sold for high prices in China.[2]

Smuggling also took place on the island for a long period of time. Pirates found that the island's abundance of hidden coves, as well as its short distance to the mainland and its small population, made it suitable for smuggling activities. Once used by smugglers of illegal Chinese immigrants, China Point, located on the south western end of Catalina, still bears its namesake.[2]

Mexican land grant

Governor Pío Pico made a Mexican land grant of the Island of Santa Catalina to Thomas M. Robbins in 1846, as Rancho Santa Catalina. Thomas M. Robbins (1801–1854) a sea captain who came to California in 1823, married the daughter of Carlos Antonio Carrillo. Robbins established a small rancho on the island, but sold it in 1850 to José María Covarrubias. A claim was filed with the Public Land Commission in 1853,[7][8] and the grant was patented to José María Covarrubias in 1867.[9] Covarrubias sold the island to Albert Packard of Santa Barbara in 1853. By 1864 the entire island was owned by James Lick, whose estate maintained control of the island for approximately the next 25 years.[10]

In the fall of 1857 the whaler Charles Melville Scammon, in the brig Boston, rendezvoused with his schooner-tender Marin in the "snug harbor" of Catalina (some have suggested Avalon Bay but it's more likely Catalina Harbor). They left on November 30 for Laguna Ojo de Liebre to become the first to hunt the gray whales breeding there.[11][12][13]

Catalina's gold rush

Three otter hunters, George Yount, Samuel Prentiss, and Stephen Bouchette, are responsible for the Island's short-lived gold rush. Yount found promising samples and, shortly before he died in 1854, told some discouraged 1849 Gold Rush miners. Samuel Prentiss, Catalina's first non-native permanent resident, was told of a buried gold treasure. He died in 1854 after spending 30 years unsuccessfully digging for it.[5]: 23–24 Just before he died, he told Stephen Bouchette of the treasure. That same year, news of Yount's promising sample began to circulate. Bouchette staked a claim and announced he had found a rich vein. He secured generous backing and spent more than $10,000 for extensive tunnels stretching over 800 feet. Some believe that there was little, if any, gold and that the claim was a ruse to get loans to dig for the lost treasure. In 1878, he and his wife loaded all they could onto a sailboat and were never seen again. Experts are still unable to determine if they found the buried treasure, were lost at sea, or simply returned to the mainland.[5]: 25–26

Word of Yount's promising samples, combined with Bouchette's well-funded claim, brought hopeful miners, and, by 1863, boom towns briefly dotted the hills. In less than one year, 10,000 feet of claims were registered, and 70 miners were actively mining these claims. Tunnels were dug by hand, and miners camped out with only one store and saloon to supply their needs. Challenged by hardship, they did enjoy the convenience of homing pigeons that delivered messages to the mainland in 45 minutes, while mail took 10 days. In 1864, the United States federal government, fearing attempts to outfit privateers by Confederate sympathizers in the American Civil War, ended the mining by ordering everyone off the island. A small garrison of Union troops was stationed at the Isthmus on the island's west end for about nine months. Their barracks stand as the oldest structure on the island and are currently the home of the Isthmus Yacht Club.

Although evidence of gold on Catalina is inconclusive, the promise of a gold-rich bonanza fueled speculation for the next few decades.[5]: 26-28

Early developers (1860–1919)

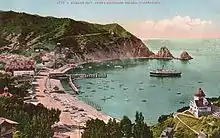

In the 1860s, German immigrant Augustus William Timms ran a sheep herding business on Catalina Island. One of his vessels, the Rosita, would also ferry pleasure seekers across the channel to Avalon Bay for bathing and fishing. The settlement in Avalon was then referred to as Timms' Landing in his honor. By the summer of 1883, there were thirty tents and three wooden buildings at Timms' Landing.[14]

.jpg.webp)

By the end of the 19th century, the island was almost uninhabited except for a few cattle herders. At that time, its location just 20 miles (30 km) from Los Angeles—a city that had reached the population of 50,000 in 1890 and was undergoing a period of enormous growth—was a major factor that contributed to the development of the island into a vacation destination.

The first owner to try to develop Avalon into a resort destination was George Shatto, a real estate speculator from Grand Rapids, Michigan. Shatto purchased the island for $200,000 from the Lick estate at the height of the real estate boom in Southern California in 1887.[16] Shatto created the settlement that would become Avalon, and can be credited with building the town's first hotel, the original Hotel Metropole, and pier.[16] Though early maps labeled the town Shatto, Shatto's sister-in-law Etta Whitney came up with the permanent name of Avalon. This name was pulled as a reference from a poem by Lord Tennyson called "Idylls of the King" about the legend of King Arthur.

Mr. and Mrs. Shatto and myself were looking for a name for the new town, which in its significance should be appropriate to the place, and the names which I was looking up were 'Avon' and 'Avondale,' and I found the name 'Avalon,' the meaning of which, as given in Webster's unabridged, was 'Bright gem of the ocean,' or Beautiful isle of the blest.'

— Etta Whitney.[10]

Shatto laid out Avalon's streets, and introduced it as a vacation destination to the general public. He did this by hosting a real estate auction in Avalon in 1887, and purchasing a steamer ship for daily access to the island. In the summer of 1888, the small pioneer village kicked off its opening season as a booming little resort town. Despite Shatto's efforts, in a few years he had to default on his loan and the island went back to the Lick estate.[17]

Avalon's oldest remaining structure, the distinctive Holly Hill House, was built on a lot purchased from Shatto and his agent C.A. Summer for $500 in 1888. Peter Gano, the engineer who built Catalina's first freshwater system, built it by himself, hauling material he had brought on his boat up the hill with the help of an old circus horse, Mercury. When it was complete in 1889, he asked the woman he loved to join him. As she refused to move to an island, he remained there alone. Restored after a fire in 1964, it is a well-known Avalon landmark.[18][5]: 36-37

.jpg.webp)

The sons of Phineas Banning bought the island in 1891 from the estate of James Lick and established the Santa Catalina Island Company to develop it as a resort. They had a variety of reasons for doing this. They wanted Catalina's rock to build a breakwater at Wilmington for their shipping company. They had also just built a luxurious new boat, the Hermosa, to bring tourists to the Island. If tourism failed, this investment was at risk. By owning Catalina, they would not only get their rock, but also money from tourists for their passage as well as everything on the island.[5]: 39-40 The Banning brothers fulfilled Shatto's dream of making Avalon a resort community with the construction of numerous tourist facilities. They built a dance pavilion in the center of town, made additions to the Hotel Metropole and steamer-wharf, built an aquarium, and created the Pilgrim Club (a gambling club for men only).[2] Although the Bannings' main focus was in Avalon, they also showed great interest in the rest of the island and wanted to introduce other parts of Catalina to the general public. They did this by paving the first dirt roads into the island's interior, where they built hunting lodges and led stagecoach tours, and by making Avalon's surrounding areas (Lovers Cove, Sugarloaf Point and Descanso Beach) accessible to tourists. They built two homes, one in Descanso Canyon and the other in what is now Two Harbors, the latter now being that village's only hotel.

Just as the Bannings were anticipating the construction of a new, Hotel Saint Catherine, their efforts were set back on November 29, 1915, when a fire burned half of Avalon's buildings, including six hotels and several clubs.[17] The Bannings refused to sell the island in hopes of rebuilding the town, starting with the Hotel Saint Catherine. The hotel would be located on Sugarloaf Point, the unique, picturesque, cliff bound peninsula at the north end of Avalon's harbor. It was blasted away to begin the construction of the hotel with its annex being in Descanso Canyon. These plans failed due to lack of funding and, in the end, the hotel was built in Descanso Canyon. In 1917 the Meteor Company purchased the Chinese pirate ship Ning Po, which was built in 1753, from her owners in Venice, California, and had her towed to the Isthmus at Catalina Island as a combination restaurant tourist attraction. The Ning Po would stay there until she was burned during a Hollywood filming in 1938.[19][20] In 1919, due to debt related to the 1915 fire and a general decline tourism during World War I, the Bannings were forced to sell the island in shares.[2]

Wrigley ownership (1919–1975)

One of the main investors to purchase shares from the Bannings was chewing-gum magnate William Wrigley, Jr. Preceding his purchase, he traveled to Catalina with his wife, Ada, and son, Philip. Reportedly, Wrigley immediately fell in love with the island and, in 1919, bought out nearly every share-holder until he owned controlling interest in the Santa Catalina Island Company.[21] Wrigley devoted himself to preserving and promoting the island, investing millions in needed infrastructure and attractions.[2] Wrigley built a home overlooking Avalon on Mount Ada, named after his wife, so he could oversee his work.[22]

When Wrigley bought the island, the Hermosa II and the SS Cabrillo were the only steamships that provided access to the island. In order to encourage growth, Wrigley purchased an additional steamship, the SS Virginia. With some adjustments, it was renamed the SS Avalon. He also foresaw the design of another steamship, the SS Catalina which was launched on the morning of May 3, 1924. These steamships would deliver passengers to Catalina for many years.[23]

One of Wrigley's first priorities was to create a new and improved dance pavilion for the island's tourists. Wrigley used Sugarloaf Point, which had originally been cleared for construction by the Banning Brothers, to build the dance hall which he named Sugarloaf Casino. It served as a ballroom and Avalon's first high-school. Its time as a casino was short, however, for it proved too small for Catalina's growing population. In 1928, the Casino was razed to make room for a newer Casino. Sugarloaf Rock was blasted away to enhance the Casino's ocean-view. On May 29, 1929, Wrigley completed the new Catalina Casino, built in the Art Deco style. The lower level of the Casino houses the Avalon Theater. The upper-level houses the world's largest circular ballroom with a 180-foot (55 m) diameter dance floor. Throughout the 1930s the Casino Ballroom hosted many of the biggest names in entertainment, including Benny Goodman, Stan Kenton, Woody Herman, and Gene Autry.[24]

Wrigley also sought to bring publicity to the island through events and spectacles. Starting in 1921, the Chicago Cubs, also owned by Wrigley, used the island for the team's spring training. Players stayed at the Hotel St. Catherine in Descanso Bay and played on a ballfield built in Avalon Canyon. The Cubs continued to use the island for spring training until 1951, except during the war years of 1942–45.[25] In another effort to bring publicity to the island, Wrigley established the Wrigley Ocean Marathon on January 15, 1927, offering a reward to the first person to swim across the channel from the mainland. The award was won by Canadian swimmer George Young, the only finisher.[26]

Following the death of Wrigley, Jr. in 1932, control of the Santa Catalina Island Company passed down to his son, Philip K. Wrigley, who continued his father's work improving the infrastructure of the island.[2] Philip continued his father's work in the improvement of the infrastructure of the City of Avalon.[2] During World War II, the island was closed to tourists and used for military training facilities.[27] Catalina's steamships were expropriated for use as troop transports and a number of military camps were established. The U.S. Maritime Service set up a training facility in Avalon, the Coast Guard had training at Two Harbors, the Army Signal Corp maintained a radar station in the interior, the Office of Strategic Services did training at Toyon Bay, and the Navy did underwater demolition training at Emerald Bay.[2][28]

In September 1972, 26 members of the Brown Berets, a group of Chicano activists, staged the Occupation of Catalina Island. They traveled to Catalina and planted a Mexican flag, claiming the island for all Chicanos. They asserted that the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty between Mexico and the United States did not specifically mention the Channel Islands. The group camped above the Chimes Tower on the point above the Casino near Avalon and were viewed as a new tourist attraction. Local Mexican-Americans provided them with food after they used up their own supplies. After 24 days a municipal judge visited the camp to ask them to leave. They departed peaceably on the tourist boat, just as they had arrived.[29]

On February 15, 1975, Philip Wrigley deeded 42,135 acres (17,051 ha) of the island from the Santa Catalina Island Company to the Catalina Island Conservancy that he had helped to establish in 1972. This gave the Conservancy control of nearly 90 percent of the island.[30] The balance of the Santa Catalina Island Company that was not deeded to the Conservancy maintains control of much of its resort properties and operations on the island. It owns and operates many of the main tourist attractions in Avalon, including the Catalina Visitors Country Club, Catalina Island Golf Course, Descanso Beach Club and the Casino Ballroom.[31]

Recent history (1975–present)

Actress Natalie Wood drowned in the waters near the settlement of Two Harbors under questionable circumstances over the Thanksgiving holiday weekend in 1981. Wood and her husband, Robert Wagner, were vacationing aboard their motor yacht, Splendour, along with their guest, Christopher Walken, and Splendour's captain, Dennis Davern. In 2011, thirty years after the actress' death, the case was reopened, partially due to public statements made by Davern.[32]

In May 2007, Catalina experienced the 2007 Avalon Fire. Greatly due to the assistance of 200 Los Angeles County fire fighters transported by U.S. Marine Corps helicopters and U.S Navy hovercraft, only a few structures were destroyed, yet 4,750 acres (19.2 km2) of wildland burned.[33][34] In May 2011, another wildfire started near the Isthmus Yacht Club and was fought by 120 firefighters transported by barge from Los Angeles. It was extinguished the next day after burning 117 acres (47 ha).[35][36]

In February 2011, water regulators cited the city for letting tens of thousands of gallons of sewage reach the ocean in six spills since 2005. A report in June 2011 by the Natural Resources Defense Council listed Avalon as having one of the 10 most chronically polluted beaches in the United States. The pollution was caused by the city's sewer system, made of century-old clay and metal pipes. By 2011, city had spent $3.5 million testing and rehabilitating sewer lines, but the water was no cleaner.[37] In February 2012, a cease and desist order was issued against the City for illegally discharging polluted water into the bay. After the cease and desist order, the city invested an additional $5.7 million on sewer main improvements and inspection and tracking systems. As a result of these efforts, the 2014 report showed that water quality had improved, and Avalon Beach was removed from the list of the most polluted beaches.[38][39]

In 2014, the Santa Catalina Island Company was working on a number of redevelopment and remodeling projects, including a spa, aquatic facility, community center, retail stores, new hotel, and 120 new homes. The largest project was a new $6-million museum building on Metropole Street to replace the old location in the Casino building. Some community members, including a then-member of the City Council, expressed concerns about the pace of the changes to the town.[40]

On August 15, 2019, the United States Coast Guard and partner agencies pulled $1M worth of marijuana bales from the ocean, which was 43 bales.[41]

On November 7, 2019, the Santa Catalina Island Company has permanently shuttered the Casino Movie Theater.[42]

On early 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the island was closed to tourists.[43]

References

- ↑ Belanger, Joe (2007). "History". Catalina Island – All You Need to Know. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Otte, Stacey; Pedersen, Jeannine (2004). "Catalina Island History". A Catalina Island History in Brief. Catalina Island Museum. Archived from the original on February 24, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ↑ Holder, Charles F. (December 16, 1899). "A California Verde Antique Quarry" (PDF). Scientific American. LXXXI (25): 393–94. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ Kroeber, Alfred Louis (July 9, 2006). Handbook of the Indians of California, Volume 2. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. pp. 620–635. ISBN 978-1-4286-4493-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Baker, Gayle. "Catalina Island", HarborTown Histories, Santa Barbara, California, 2002, p. 7, ISBN 0-9710984-0-9 (print), 978-0-9879038-0-8 (on-line)

- ↑ Watson, Jim (August 7, 2012). "Where in the world is Juan Cabrillo?". The Catalina Islander. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

Many historians originally believed he was Portuguese and not Spanish...This assertion, however, has been basically debunked and explained as an error attributed to a single historian or perhaps even to a printing error.

- ↑ United States. District Court (California : Southern District) Land Case 368 SD

- ↑ Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1892

- ↑ "Microsoft Word – Surveyor General Report for 1884–1886 _Willey_.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- 1 2 Williamson, M. Burton (December 7, 1903). "History of Santa Catalina Island". The Historical Society of Southern California. Los Angeles: George Rice & Sons: 14–31.

- ↑ Scammon, Charles (1874). The Marine Mammals of the North-western Coast of North America: Together with an Account of the American Whale-fishery. Dover. ISBN 0-486-21976-3.

- ↑ Henderson, David A. (1972). Men & Whales at Scammon's Lagoon. Los Angeles: Dawson's Book Shop.

- ↑ Landauer, Lyndall Baker (1986). Scammon: Beyond the Lagoon: A Biography of Charles Melville Scammon. San Francisco: Associates of the J. Porter Shaw Library in cooperation with the Institute for Marine Information.

- ↑ Daily, Marla (2012). The California Channel Islands. Arcadia Pub. ISBN 9780738595085.

- ↑ "Santa Catalina Island Incline Railway". erha.org. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Gelt, Jessica (January 7, 2007). "A Day In; 90704; Pleasure Cruising in Avalon". Los Angeles Times. pp. I.9. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- 1 2 "The Evolution of a Resort Community". Catalina Island History. eCatalina. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ Satzman, Darrell (November 28, 2010). "A quirky bachelor pad on Catalina". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ↑ Grey, Zane.(2000) P. 152. "Tales of Swordfish and Tuna." The Derrydale Press. Lanham and New York.

- ↑ Islapedia-Ning Po, October 9, 2022; on line

- ↑ "Wrigley Buys Catalina Island". Los Angeles Times. February 13, 1919. pp. II1. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ↑ "The Inn on Mt. Ada". The Inn on Mt. Ada. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ↑ Pederson, Jeannine L.; Museum, the Catalina Island (2006). Catalina by Sea : A Transportation History. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 0738531162. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ↑ McClure, Rosemary (June 19, 2009). "Backstage at Catalina Island's Avalon Casino". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ "The Chicago Cubs spring training & clubhouse". eCatalina.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ Rainey, James (October 18, 2005). "Crossing the icy waters for posterity". Los Angeles Times. pp. F5. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Catalina Island Life During World War II, by Jeannine Pedersen, Curator of Collections, Catalina Island Museum". Ecatalina.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ↑ "About Emerald Bay". Camp Emerald Bay. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ↑ Martinez, Al (September 23, 1972). "Judge Asks Berets to Leave – They Do". Los Angeles Times. p. B1. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". Catalina Island Conservancy. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ↑ "About Us". Santa Catalina Island Company. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ↑ "Natalie Wood Death – Homicide Investigation Re-Opened". TMZ.com. November 17, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ↑ Sahagun, L. and S. Quinones. 2007. Catalina fire lays siege to Avalon: Hundreds of residents and tourists are forced to flee the island. Los Angeles Times. 11 May.

- ↑ Seema, Mehta; Rosenblatt, Susannah (May 12, 2007). "Catalina Fire: A New Day; After such a huge threat, Avalon's loss is small". Los Angeles Times. p. A1. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ↑ Lopez, Robert (May 3, 2011). "Firefighters contain Catalina brush fire". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ↑ Blankstein, Andrew (May 2, 2011). "Catalina fire threatens yacht club; 100 firefighters sent to island by barge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ↑ Barboza, Tony (July 10, 2011). "Avalon's dirty little secret: its beach is health hazard". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013.

- ↑ Barboza, Tony (May 22, 2014). "Drought has upside: record-low rainfall means cleaner beach water". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ↑ "2013-2014 Annual Beach Report Card" (PDF). Heal the Bay. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ↑ Sahagun, Louis (March 22, 2014). "Catalina's Avalon is getting an ambitious overhaul". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ "$1M worth of marijuana bales pulled from ocean near Catalina Island, authorities say". ABC7 Los Angeles. 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ Rubin, Rebecca (November 12, 2019). "Avalon Theatre Owner Blames Streaming Services for 'Upside-Down' Attendance". Variety. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ↑ Reynolds, Christopher (March 27, 2020). "Escape to Catalina? No, it's closed up tight". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 29, 2020.