The Cayman Islands are a British overseas territory located in the Caribbean that have been under various governments since their discovery by Europeans. Christopher Columbus sighted the Cayman Islands on May 10, 1503, and named them Las Tortugas after the numerous sea turtles seen swimming in the surrounding waters. Columbus had found the two smaller sister islands (Cayman Brac and Little Cayman) and it was these two islands that he named "Las Tortugas".

The 1523 "Turin map" of the islands was the first to refer to them as Los Lagartos, meaning alligators or large lizards,[1] By 1530 they were known as the Caymanes after the Carib word caimán for the marine crocodile, either the American or the Cuban crocodile, Crocodylus acutus or C. rhombifer, which also lived there. Recent sub-fossil findings suggest that C. rhombifer, a freshwater species, were prevalent until the 20th century.

Settlement

Archaeological studies of Grand Cayman have found no evidence that humans occupied the islands prior to the sixteenth century.[2]

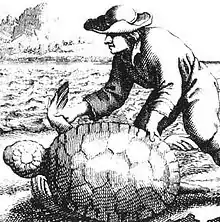

The first recorded English visitor was Sir Francis Drake in 1586, who reported that the caymanas were edible, but it was the turtles which attracted ships in search of fresh meat for their crews. Overfishing nearly extinguished the turtles from the local waters. Turtles were the main source for an economy on the islands. In 1787, Captain Hull of HMS Camilla estimated between 1,200 and 1,400 turtles were captured and sold at seaports in Jamaica per year. According to historian Edward Long the inhabitants on Grand Cayman had the principal occupation of turtle-fishery. Once Caymanian turtlers greatly reduced the turtle population around the islands they journeyed to the waters of other islands in order to maintain their livelihood.[3]

Caymanian folklore explains that the island's first inhabitants were Ebanks and his companion named Bawden (or Bodden), who first arrived in Cayman in 1658 after serving in Oliver Cromwell's army in Jamaica.[4] The first recorded permanent inhabitant of the Cayman Islands, Isaac Bodden, was born on Grand Cayman around 1700. He was the grandson of the original settler named Bodden.

Most, if not all, early settlers were people who came from outside of the Cayman Islands and were on the fringes of society. Due to this, the Cayman Islands have often been described as "a total colonial frontier society": effectively lawless during the early settlement years. The Cayman Islands remained a frontier society until well into the twentieth century.[5] The year 1734 marked the rough beginning period of permanent settlement in Grand Cayman. Cayman Brac and Little Cayman were not permanently settled until 1833.[6] A variety of people settled on the islands: pirates, refugees from the Spanish Inquisition, shipwrecked sailors, and slaves. The majority of Caymanians are of African, Welsh, Scottish or English descent, with considerable interracial mixing.[7]

During the early years, settlements on the north and west sides of Grand Cayman were often subject to raids by Spanish forces coming from Cuba.[8] On 14 April 1669, the Spanish Privateer Rivero Pardal completed a successful raid on the village of Little Cayman. In the process of the raid, the forces burned twenty dwellings to the ground.[6]

Those living on the islands often partook in what is called "wrecking". Caymanians enticed passing ships by creating objects that piqued sailors' interests. Often these objects did not look like other vessels. Caymanians made mules or donkeys with lanterns tied to their bodies to walk along the beaches or lit a large bonfire to attract sailors. Having very little knowledge of the area, sailors often became stuck on the reefs in the process of reaching a distance to where they could communicate with those on the island. Once the ships were stuck on the reefs, islanders took canoes to plunder and salvage the ships under the false pretense of providing assistance.[9]

British control

England took formal control of Cayman, along with Jamaica, under the Treaty of Madrid in 1670[10] after the first settlers came from Jamaica in 1661–71 to Little Cayman and Cayman Brac. These first settlements were abandoned after attacks by Spanish privateers, but English privateers often used the Cayman Islands as a base and in the 18th century they became an increasingly popular hideout for pirates, even after the end of legitimate privateering in 1713. Following several unsuccessful attempts, permanent settlement of the islands began in the 1730s. In the early morning hours of February 8, 1794, ten vessels which were part of a convoy escorted by HMS Convert, were wrecked on the reef in Gun Bay, on the East end of Grand Cayman. Despite the darkness and pounding surf on the reef, local settlers braved the conditions attempting to rescue the passengers and crew of the fledgling fleet. There are conflicting reports, but it is believed that between six, and eight people died that night, among them, the Captain of the Britannia. However, the overwhelming majority, more than 450 people, were successfully rescued. The incident is now remembered as The Wreck of the Ten Sail. Legend has it that among the fleet, there was a member of the British Royal Family on board. Most believe it to be a nephew of King George III. To reward the bravery of the island's local inhabitants, King George III reportedly issued a decreed that Caymanians should never be conscripted for war service, and shall never be subject to taxation. However, no official documentation of this decree has been found. All evidence for this being the origin of their tax-free status is purely anecdotal. Regardless, the Cayman Islands' status as a tax-free British overseas territory remains to this day.

From 1670, the Cayman Islands were effective dependencies of Jamaica, although there was considerable self-government. In 1831, a legislative assembly was established by local consent at a meeting of principal inhabitants held at Pedro St. James Castle on December 5 of that year. Elections were held on December 10 and the fledgling legislature passed its first local legislation on December 31, 1831. Subsequently, the Jamaican governor ratified a legislature consisting of eight magistrates appointed by the Governor of Jamaica and 10 (later increased to 27) elected representatives.

The collapse of the Federation of the West Indies created a period of decolonization in the English-speaking Caribbean.[11] In regards to independence, of the six dependent territories, the Cayman Islands were the most opposed because it lacked the natural resources needed. This opposition came from the fear that independence might prevent any special United States visas that aided Caymanian sailors working on American ships and elsewhere in the United States.[12] The people had concerns about their economic viability if the country was to become independent. The Cayman Islands were not the only smaller British territory that was reluctant in regards to gaining independence. The United Kingdom authorities established a new governing constitution framework for the reluctant territories. In place of the Federation of the West Indies, a constitution was created that allowed for the continuation of formal ties with London. In the Cayman Islands, the Governor's only obligation to the British Crown is that of keeping the Executive Council informed.[13]

Slavery

Grand Cayman was the only island of the three that had institutionalized slavery. Although slavery was instituted, Grand Cayman did not have violent slave revolts. While scholars tend to agree that to an extent a slave society existed on at least Grand Cayman, there are debates among them on how important slavery was to the society as a whole.[14] The slave period for the Cayman Islands lasted between 1734 and 1834. In 1774, George Gauld estimated that approximately four hundred people lived on Grand Cayman; half of the inhabitants were free while the other half were constituted slaves. By 1802, of 933 inhabitants, 545 people were owned by slave owners. An April 1834 census recorded a population of 1,800 with roughly 46 percent considered free Caymanians. By the time of emancipation, enslaved people outnumbered that of slave owners or non-enslaved people on Grand Cayman.[15] In 1835, Governor Sligo arrived in Cayman from Jamaica to declare all enslaved people free in accordance with the British Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

Caymanian settlers resented their administrative association with Jamaica, which caused them to seize every opportunity to undermine the authorities. This problematic relationship reached its peak during the period leading up to emancipation in 1835. Caymanian slave owners who did not want to give up the free labour they extracted from their human chattel refused to obey changes in British legislation outlawing slavery. In response to the Slave Trade Act 1807, the Slave Trade Felony Act 1811, and the Emancipation Act 1834, slave owners organized resistance efforts against the authorities in Jamaica.[16]

Local White residents of the Cayman Islands also resisted the stationing of troops of the West India Regiment. This animosity stemmed from the fact that the West India Regiment enlisted Black men, which the White establishment opposed because they were 'insulted' at the idea of Black soldiers defending their settlements.[17]

Dependency of Jamaica

The Cayman Islands were officially declared and administered as a dependency of Jamaica from 1863 but were rather like a parish of Jamaica with the nominated justices of the peace and elected vestrymen in their Legislature. From 1750 to 1898 the Chief Magistrate was the administrating official for the dependency, appointed by the Jamaican governor. In 1898 the Governor of Jamaica began appointing a Commissioner for the Islands. The first Commissioner was Frederick Sanguinetti. In 1959, upon the formation of the Federation of the West Indies the dependency status with regards to Jamaica ceased officially although the Governor of Jamaica remained the Governor of the Cayman Islands and had reserve powers over the islands. Starting in 1959 the chief official overseeing the day-to-day affairs of the islands (for the Governor) was the Administrator. Upon Jamaica's independence in 1962, the Cayman Islands broke its administrative links with Jamaica and opted to become a direct dependency of the British Crown, with the chief official of the islands being the Administrator.

In 1953 the first airfield in the Cayman Islands was opened as well as the George Town Public hospital. Barclays ushered in the age of formalised commerce by opening the first commercial bank.

Governmental changes

Following a two-year campaign by women to change their circumstances, in 1959 Cayman received its first written constitution which, for the first time, allowed women to vote. Cayman ceased to be a dependency of Jamaica.

During 1966, legislation was passed to enable and encourage the banking industry in Cayman.

In 1971, the governmental structure of the islands was again changed, with a governor now running the Cayman Islands. Athel Long CMG, CBE was the last administrator and the first governor of the Cayman Islands.

In 1991, a review of the 1972 constitution recommended several constitutional changes to be debated by the Legislative Assembly. The post of chief secretary was reinstated in 1992 after having been abolished in 1986. The establishment of the post of chief minister was also proposed. However, in November 1992 elections were held for an enlarged Legislative Assembly and the Government was soundly defeated, casting doubt on constitutional reform. The "National Team" of government critics won 12 (later reduced to 11) of the 15 seats, and independents won the other three, after a campaign opposing the appointment of chief minister and advocating spending cuts. The unofficial leader of the team, Thomas Jefferson, had been the appointed financial secretary until March 1992, when he resigned over public spending disputes to fight the election. After the elections, Mr. Jefferson was appointed minister and leader of government business; he also held the portfolios of Tourism, Aviation and Commerce in the executive council. Three teams with a total of 44 candidates contested the general election held on November 20, 1996: the governing National Team, Team Cayman and the Democratic Alliance Group. The National Team were returned to office but with a reduced majority, winning 9 seats. The Democratic Alliance won 2 seats in George Town, Team Cayman won one in Bodden Town and independents won seats in George Town, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman.

Although all administrative links with Jamaica were broken in 1962, the Cayman Islands and Jamaica continue to share many links, including a common united church (the United Church in Jamaica and the Cayman Islands) and Anglican diocese (although there is debate about this). They also shared a common currency until 1972. In 1999, 38–40% of the expat population of the Cayman Islands was of Jamaican origin and in 2004/2005 little over 50% of the expatriates working in the Cayman Islands (i.e. 8,000) were Jamaicans (with the next largest expatriate communities coming from the United States, United Kingdom and Canada).

Hurricane Ivan

In September 2004, The Cayman Islands were hit by Hurricane Ivan, causing mass devastation, loss of animal life (both wild and domestic/livestock) and flooding; however, there was no loss of human life. Some accounts reported that the majority of Grand Cayman had been underwater and with the lower floors of some buildings being completely flooded in excess of 8 ft. An Ivan Flood Map is available from the Lands & Survey Dept. of The Cayman Islands indicating afflicted areas and their corresponding flood levels.[18] This natural disaster also led to the bankruptcy of a heavily invested insurance company called Doyle. The company had re-leased estimates covering 20% damage to be re-insured at minimal fees when in fact the damage was over 65% and every claim was in the millions. The company simply could not keep paying out and the adjusters could not help lower the payments due to the high building code the Islands adhere to.

Much suspense was built around the devastation that Hurricane Ivan had caused as the leader of Government business Mr. Mckeeva Bush decided to close the Islands to any and all reporters, aid and denied permissions to land any aircraft except for Cayman Airways. The line of people wishing to leave, but unable to do so, extended from the airport to the post office each day, as thousands who were left stranded with no shelter, food, or fresh water hoped for a chance to evacuate. As a result, most evacuations and the mass exodus which ensued in the aftermath was done so by private charter through personal expense, with or without official permission. It was also a collective decision within the government at that time to turn away two British warships that had arrived the day after the storm with supplies. This decision was met by outrage from the Islanders who thought that it should have been their decision to make. Power and water was cut off due to damaged pipes and destroyed utility poles, with all utilities restored to various areas over the course of the next three months. Fortis Inc., a Canadian-owned utility company, sent a team down to Grand Cayman to assist the local power company, CUC, with restoration. The official report, extent of damage, duration and recovery efforts in the words of Mr. Bush himself are first recorded a month following to the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs Written Evidence, Letter from the Cayman Islands Government Office in the United Kingdom, 8 October 2004.[19]

"Hurricane Ivan weakened to a category four hurricane as it moved over Grand Cayman. It is the most powerful hurricane ever to hit the cayman islands. The eye of the storm passed within eight to 15 miles of Grand Cayman. It struck on Sunday 12 September, bringing with it sustained winds of 155 miles per hour, gusts of up to 217 mph, and a storm surge of sea water of eight to 10 feet, which covered most of the Island. A quarter of Grand Cayman remained submerged by flood waters two days later. Both Cayman Brac and Little Cayman suffered damage, although not to the same extent as Grand Cayman.

Damage on Grand Cayman has been extensive. "I include with this letter, for your reference, a detailed briefing about the damage and the recovery effort, and some photographs of the devastation. 95% of our housing stock has sustained damage, with around 25% destroyed or damaged beyond repair. We currently have 6,000 homes that are uninhabitable-these are homes that house teachers, nurses, manual and other workers. Thankfully, loss of life in Cayman has been limited, relative to the impact of the storm."- Honourable McKeeva Bush, OBE, JP.[19]

While there still remains visible signs of damage, in the vegetation and destruction to buildings particularly along the southern and eastern coastal regions, the Island took considerable time to become suitable as a bustling financial & tourism destination again. There remain housing issues for many of the residents as of late 2005, with some buildings still lying derelict due to insurance claims as of 2013, feasibility, new regulations and building codes. Many residents simply were unable to rebuild, and abandoned the damaged structures.

References

- ↑ Roger C. Smith, The maritime heritage of the Cayman Islands, 2000 p.26

- ↑ Stokes, Anne V.; Keegan, William F. (April 1993). "A SETTLEMENT SURVEY FOR PREHISTORIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES ON GRAND CAYMAN". Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Christopher (2011). "Did Slavery Really Matter in the Cayman Islands?". The Journal of Caribbean History. 45: 165.

- ↑ National Trust for the Cayman Islands (29 Nov 2011). "Watler Cemetery". National Trust for the Cayman Islands. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ Bodden, J. A. Roy (2007). The Cayman Islands in Transition: The Politics, History, and Sociology of a Changing Society. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers. pp. 3, 7, 6.

- 1 2 Williams, Christopher (2011). "Did Slavery Really Matter in the Cayman Islands?". The Journal of Caribbean History. 45: 160.

- ↑ "Cayman History | Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac, Little Cayman | Cayman Islands". Caymanislands.ky. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- ↑ Bodden, J. A. Roy (2007). The Cayman Islands in Transition: The Politics, History, and Sociology of a Changing Society. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers. p. 3.

- ↑ Bodden, J. A. Roy (2007). The Cayman Islands in Transition: The Politics, History, and Sociology of a Changing Society. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers. p. 5.

- ↑ Neville Williams (1970). A history of the Cayman Islands. Government of the Cayman Islands. p. 10. ISBN 978-976-8104-13-7.

- ↑ Foote, Nicola (2013). The Caribbean History Reader. New York: Routledge. p. 313.

- ↑ Ramos Aaron Gamaliel, Rivera Angel Israel (2001). Islands at the Crossroads: Politics in the Non-Independent Caribbean. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers. p. 120.

- ↑ Foote, Nicola (2013). The Caribbean History Reader. New York: Routledge. pp. 309, 313, 314.

- ↑ Williams, Christopher A. (Winter 2013). "Premature Abolition, Ethnocentrism, and Bold Blackness: Race Relations in the Cayman Islands". The Historian. 75: 785, 786. doi:10.1111/hisn.12021. S2CID 145793092.

- ↑ Williams, Christopher (2011). "Did Slavery Really Matter in the Cayman Islands?". The Journal of Caribbean History. 45: 160–162.

- ↑ Bodden, J. A. Roy (2007). The Cayman Islands in Transition: The Politics, History, and Sociology of a Changing Society. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers. p. 8.

- ↑ Bodden, J. A. Roy (2007). The Cayman Islands in Transition: The Politics, History, and Sociology of a Changing Society. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers. p. 12.

- ↑ "Cayman Islands Flooding" (JPG). Caymanislandinfo.ky. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- 1 2 "House of Commons - Foreign Affairs - Written Evidence". Publications.parliament.uk.

External links

![]() Media related to History of the Cayman Islands at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of the Cayman Islands at Wikimedia Commons