The known human history of the Grand Canyon area stretches back 10,500 years, when the first evidence of human presence in the area is found. Native Americans have inhabited the Grand Canyon and the area now covered by Grand Canyon National Park for at least the last 4,000 of those years. Ancestral Pueblo peoples, first as the Basketmaker culture and later as the more familiar Pueblo people, developed from the Desert Culture as they became less nomadic and more dependent on agriculture. A similar culture, the Cochimi also lived in the canyon area. Drought in the late 13th century likely caused both groups to move on. Other people followed, including the Paiute, Cerbat, and the Navajo, only to be later forced onto reservations by the United States Government.

In September 1540, under direction by conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to find the fabled Seven Cities of Gold, Captain García López de Cárdenas led a party of Spanish soldiers with Hopi guides to the Grand Canyon. More than 200 years passed before two Spanish priests became the second party of non-Native Americans to see the canyon. U.S. Army Major John Wesley Powell led the 1869 Powell Geographic Expedition through the canyon on the Colorado River. This and later study by geologists uncovered the geology of the Grand Canyon area and helped to advance that science. In the late 19th century, the promise of mineral resources—mainly copper and asbestos—renewed interest in the region. The first pioneer settlements along the rim came in the 1880s.

Early residents soon realized that tourism was destined to be more profitable than mining, and by the turn of the 20th century the Grand Canyon was a well-known tourist destination. Most visitors made the gruelling trip from nearby towns to the South Rim by stagecoach. In 1901 the Grand Canyon Railway was opened from Williams, Arizona, to the South Rim, and the development of formal tourist facilities, especially at Grand Canyon Village, increased dramatically. The Fred Harvey Company developed many facilities at the Grand Canyon, including the luxury El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim in 1905 and Phantom Ranch in the Inner Gorge in 1922. Although first afforded federal protection in 1893 as a forest reserve and later as a U.S. National Monument, the Grand Canyon did not achieve U.S. National Park status until 1919, three years after the creation of the National Park Service. Today, Grand Canyon National Park receives about five million visitors each year, a far cry from the annual visitation of 44,173 in 1919.

Early history

Current archaeological evidence suggests that humans inhabited the Grand Canyon area as far back as 4,000 years ago[1] and at least were passers-through for 6,500 years before that.[2] Radiocarbon dating of artifacts found in limestone caves in the inner canyon indicate ages of 3,000 to 4,000 years.[1] In the 1950s split-twig animal figurines were found in the Redwall Limestone cliffs of the Inner Gorge that were dated in this range. These animal figurines are a few inches (7 to 8 cm) in height and made primarily from twigs of willow or cottonwood.[1] This and other evidence suggests that these inner canyon dwellers were part of Desert Culture; a group of semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer Native American. The Ancestral Pueblo of the Basketmaker III Era (also called the Histatsinom, meaning "people who lived long ago") evolved from the Desert Culture sometime around 500 BCE.[1] This group inhabited the rim and inner canyon and survived by hunting and gathering along with some limited agriculture. Noted for their basketmaking skills (hence their name), they lived in small communal bands inside caves and circular mud structures called pithouses. Further refinement of agriculture and technology led to a more sedentary and stable lifestyle for the Ancestral Pueblo starting around 500 CE.[1] Contemporary with the flourishing of Ancestral Pueblo culture, another group, called the Cohonina lived west of the current site of Grand Canyon Village.[1]

Ancestral Pueblo in the Grand Canyon area started to use stone in addition to mud and poles to erect above-ground houses sometime around 800 CE.[1] Thus the Pueblo period of Ancestral Pueblo culture was initiated. In summer, the Puebloans migrated from the hot inner canyon to the cooler high plateaus and reversed the journey for winter.[1] Large granaries and multi-room pueblos survive from this period. There are around 2,000 known Ancestral Pueblo archaeological sites in park boundaries. The most accessible site is Tusayan Pueblo, which was constructed sometime c. 1185 and housed 30 or so people.[3]

Large numbers of dated archaeological sites indicate that the Ancestral Pueblo and the Cohonina flourished until about 1200 CE.[1] But something happened a hundred years later that forced both of these cultures to move away. Several lines of evidence led to a theory that climate change caused a severe drought in the region from 1276 to 1299, forcing these agriculture-dependent cultures to move on.[4] Many Ancestral Pueblo relocated to the Rio Grande and the Little Colorado River drainages, where their descendants, the Hopi and the 19 Pueblos of New Mexico, now live.[3]

For approximately one hundred years the canyon area was uninhabited by humans.[1] Paiute from the east and Cerbat from the west were the first humans to reestablish settlements in and around the Grand Canyon.[1] The Paiute settled the plateaus north of the Colorado River and the Cerbat built their communities south of the river, on the Coconino Plateau. The Navajo, or the Diné, arrived in the area later.

All three cultures were stable until the United States Army moved them to Indian reservations in 1882 as part of the removal efforts that ended the Indian Wars.[1] The Havasupai and Hualapai are descended from the Cerbat and still live in the immediate area. The village of Supai in the western part of the current park has been occupied for centuries. Adjacent to the eastern part of the park is the Navajo Nation, the largest reservation in the United States.

European exploration

Spanish

The first Europeans reached the Grand Canyon in September 1540.[1] It was a group of about 13 Spanish soldiers led by García López de Cárdenas, dispatched from the army of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado on its quest to find the fabulous Seven Cities of Gold.[2][5][6] The group was led by Hopi guides and, assuming they took the most likely route, must have reached the canyon at the South Rim, probably between today's Desert View and Moran Point. According to Castañeda, he and his company came to a point "from whose brink it looked as if the opposite side must be more than three or four leagues by air line."[7]

The report indicates that they greatly misjudged the proportions of the gorge. On the one hand, they estimated that the canyon was about three to four leagues wide (13–16 km, 8–10 mi), which is quite accurate.[5] At the same time, however, they believed that the river, which they could see from above, was only 2 m (6 ft) wide (in reality it is about a hundred times wider).[5] Being in dire need of water, and wanting to cross the giant obstacle, the soldiers started searching for a way down to the canyon floor that would be passable for them along with their horses. After three full days, they still had not been successful, and it is speculated that the Hopi, who probably knew a way down to the canyon floor, were reluctant to lead them there.[5]

As a last resort, Cárdenas finally commanded the three lightest and most agile men of his group to climb down by themselves (their names are given as Pablo de Melgosa, Juan Galeras, and an unknown, third soldier).[5] After several hours, the men returned, reporting that they had only made one third of the distance down to the river, and that "what seemed easy from above was not so".[5] Furthermore, they claimed that some of the boulders which they had seen from the rim, and estimated to be about as tall as a man, were in fact bigger than the Great Tower of Seville, at 104.1 m (342 ft). Cárdenas finally had to give up and returned to the main army. His report of an impassable barrier forestalled further visitation to the area for two hundred years.

Only in 1776 did two Spanish Priests, Fathers Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante travel along the North Rim again, together with a group of Spanish soldiers, exploring southern Utah in search of a route from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Monterey, California.[1] Also in 1776, Fray Francisco Garces, a Franciscan missionary, spent a week near Havasupai, unsuccessfully attempting to convert a band of Native Americans. He described the canyon as "profound".[8]

Americans

James Ohio Pattie and a group of American trappers and mountain men were probably the next Europeans to reach the canyon in 1826,[9] although there is little supporting documentation.

The signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 ceded the Grand Canyon region to the United States. Jules Marcou of the Pacific Railroad Survey made the first geologic observations of the canyon and surrounding area in 1856.[2]

Jacob Hamblin (a Mormon missionary) was sent by Brigham Young in the 1850s to locate easy river crossing sites in the canyon.[10] Building good relations with local Native Americans and white settlers, he discovered Lee's Ferry in 1858 and Pierce Ferry (later operated by, and named for, Harrison Pierce)—the only two sites suitable for ferry operation.[11]

In 1857 Edward Fitzgerald Beale led an expedition to survey a wagon road from Fort Defiance, Arizona to the Colorado River.[12] On September 19 near present-day National Canyon they came upon what May Humphreys Stacey described in his journal as "a wonderful canyon four thousand feet deep. Everyone (in the party) admitted that he never before saw anything to match or equal this astonishing natural curiosity."[13]

A U.S. War Department expedition led by Lt. Joseph Ives was launched in 1857 to investigate the area's potential for natural resources, to find railroad routes to the west coast, and assess the feasibility of an up-river navigation route from the Gulf of California.[2] The group traveled in a stern wheeler steamboat named Explorer. After two months and 350 miles (560 km) of difficult navigation, his party reached Black Canyon some two months after George Johnson.[14] In the process, the Explorer struck a rock and was abandoned. The group later traveled eastwards along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

A man of his time, Ives discounted his own impressions on the beauty of the canyon and declared it and the surrounding area as "altogether valueless", remarking that his expedition would be "the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality".[15] Attached to Ives' expedition was geologist John Strong Newberry who had a very different impression of the canyon.[2] After returning, Newberry convinced fellow geologist John Wesley Powell that a boat run through the Grand Canyon to complete the survey would be worth the risk.[16][lower-alpha 1] Powell was a major in the United States Army and was a veteran of the American Civil War, a conflict that cost him his right forearm in the Battle of Shiloh.[2]

More than a decade after the Ives Expedition and with help from the Smithsonian Institution, Powell led the first of the Powell Expeditions to explore the region and document its scientific offerings.[6] On May 24, 1869, the group of nine men set out from Green River Station in Wyoming down the Colorado River and through the Grand Canyon.[2] This first expedition was poorly funded and consequently no photographer or graphic artist was included. While in the Canyon of Lodore one of the group's four boats capsized, spilling most of their food and much of their scientific equipment into the river. This shortened the expedition to one hundred days. Tired of being constantly cold, wet and hungry and not knowing they had already passed the worst rapids, three of Powell's men climbed out of the canyon in what is now called Separation Canyon.[18] Once out of the canyon, all three were reportedly killed by Shivwits band Paiutes who thought they were miners that recently molested and killed a female Shivwit.[18] All those who stayed with Powell survived and that group successfully ran most of the canyon.

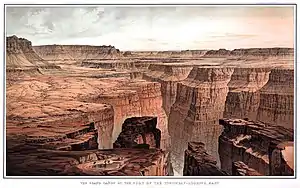

Two years later a much better-funded Powell-led party returned with redesigned boats and a chain of several supply stations along their route. This time, photographer E.O. Beaman and 17-year-old artist Frederick Dellenbaugh were included.[18] Beaman left the group in January 1872 over a dispute with Powell and his replacement, James Fennemore, quit August that same year due to poor health, leaving boatman John K. Hillers as the official photographer (nearly one ton of photographic equipment was needed on site to process each shot).[19] Famed painter Thomas Moran joined the expedition in the summer of 1873, after the river voyage and thus only viewed the canyon from the rim. His 1873 painting "Chasm of the Colorado" was bought by the United States Congress in 1874 and hung in the lobby of the Senate.[20]

The Powell expeditions systematically cataloged rock formations, plants, animals, and archaeological sites. Photographs and illustrations from the Powell expeditions greatly popularized the canyonland region of the southwest United States, especially the Grand Canyon (appreciating this, Powell added increasing resources to that aspect of his expeditions). Powell later used these photographs and illustrations in his lecture tours, making him a national figure. Rights to reproduce 650 of the expeditions' 1,400 stereographs were sold to help fund future Powell projects.[21] In 1881 he became the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Geologist Clarence Dutton followed up on Powell's work in 1880–1881 with the first in-depth geological survey of the newly formed U.S. Geological Survey.[22] Painters Thomas Moran and William Henry Holmes accompanied Dutton, who was busy drafting detailed descriptions of the area's geology. The report that resulted from the team's effort was titled A Tertiary History of The Grand Canyon District, with Atlas and was published in 1882.[22] This and later study by geologists uncovered the geology of the Grand Canyon area and helped to advance that science. Both the Powell and Dutton expeditions helped to increase interest in the canyon and surrounding region.

The Brown-Stanton expedition was started in 1889 to survey the route for a "water-level" railroad line through the canyons of the Colorado River to the Gulf of California.[23] The proposed Denver, Colorado Canyon, and Pacific Railway was to carry coal from mines in Colorado. Expedition leader Frank M. Brown, his chief engineer Robert Brewster Stanton, and 14 other men set out in six boats from Green River, Utah, on May 25, 1889.[23] Brown and two others drowned near the head of Marble Canyon. The expedition was restarted by Stanton from Dirty Devil River (a tributary of Glen Canyon) on November 25 and traveled through the Grand Canyon.[23] The expedition reached the Gulf of California on April 26, 1890 but the railroad was never built.

Prospectors in the 1870s and 1880s staked mining claims in the canyon.[22] They hoped that previously discovered deposits of asbestos, copper, lead, and zinc would be profitable to mine. Access to and from this remote region and problems getting ore out of the canyon and its rock made the whole exercise not worth the effort. Most moved on, but some stayed to seek profit in the tourist trade. Their activities did improve pre-existing Indian trails, such as Bright Angel Trail.[3]

Tourism

Transportation

A rail line to the largest city in the area, Flagstaff, was completed in 1882 by the Santa Fe Railroad.[24] Stage coaches started to bring tourists from Flagstaff to the Grand Canyon the next year—an eleven-hour trip greatly reduced in 1901 when a spur of the Santa Fe Railroad to Grand Canyon Village was completed.[22] The first scheduled train with paying passengers of the Grand Canyon Railway arrived from Williams, Arizona, on September 17 that year.[24] The 64-mile (103 km) long trip cost $3.95 ($119.78 as of 2024), and naturalist John Muir later commended the railroad for its limited environmental impact.[24]

The first automobile was driven to the Grand Canyon in January 1902. Oliver Lippincott from Los Angeles, drove his American Bicycle Company built Toledo steam car to the South Rim from Flagstaff. Lippincott, Al Doyle a guide from Flagstaff and two writers set out on the afternoon of January 2, anticipating a seven-hour journey. Two days later, the hungry and dehydrated party arrived at their destination; the countryside was just too rough for the ten-horsepower (7 kW) auto. Winfield Hoggaboon, one of the writers on the trip, wrote an amusing and detailed three page article in the Los Angeles Herald Illustrated Magazine on February 2, 1902, "To the Grand Canyon by Automobile". A three-day drive from Utah in 1907 was required to reach the North Rim for the first time.[24]

Competition with the automobile forced the Santa Fe Railroad to cease operation of the Grand Canyon Railway in 1968 (only three passengers were on the last run). The railway was restored and service reintroduced in 1989, and it has since carried hundreds of passengers a day. Trains remained the preferred way to travel to the canyon until they were surpassed by the auto in the 1930s. By the early 1990s more than a million automobiles per year visited the park.

West Rim Drive was completed in 1912. In the late 1920s the first rim-to-rim access was established by the North Kaibab suspension bridge over the Colorado River.[22] Paved roads did not reach the less popular and more remote North Rim until 1926, and that area, being higher in elevation, is closed due to winter weather from November to April. Construction of a road along part of the South Rim was completed in 1935.[22]

Air pollution

The primary mobile source of Grand Canyon haze, the automobile, is currently regulated under a series of federal, state and local initiatives. The Grand Canyon Visibility Transport Commission cites U.S. government laws regulating automobile emissions and gasoline standards, often slow to change because of the automobile industry's planning schedule, as a primary contributor to air quality issues in the area.[25] They advocate policies leaning toward stricter emission standards via cleaner burning fuel and improved automobile emissions technology.

Air pollution from those vehicles and wind-blown pollution from Las Vegas, Nevada area has reduced visibility in the Grand Canyon and vicinity. During the past decade, various regional coal-fired electric utilities having little or no pollution control equipment were targeted as the primary stationary sources of Grand Canyon air pollution.[26] In the 1980s the Navajo Generating Station at Page, Arizona, (15 miles away) was identified as the primary source for anywhere from fifty percent to ninety percent of the Grand Canyon's air quality problems.[25] In 1999, the Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, (75) miles away settled a long-standing lawsuit and agreed to install end-of-point sulfur scrubbers on its smoke stacks.

Closer to home, there is little disagreement that the most visible of the park's visibility problems stems from the park's popularity. On any given summer day the park is filled to capacity, or over-capacity. Basically the problem boils down to too many private automobiles vying for too few parking spaces. Emissions from all those automobiles and tour buses contributes greatly to air pollution problems.

Accommodations

John D. Lee was the first person who catered to travelers to the canyon. In 1872 he established a ferry service at the confluence of the Colorado and Paria rivers. Lee was in hiding, having been accused of leading the Mountain Meadows massacre in 1857. He was tried and executed for this crime in 1877. During his trial he played host to members of the Powell Expedition who were waiting for their photographer, Major James Fennemore, to arrive (Fennemore took the last photo of Lee sitting on his own coffin). Emma, one of Lee's nineteen wives, continued the ferry business after her husband's death. In 1876 a man named Harrison Pierce established another ferry service at the western end of the canyon.[24]

The two-room Farlee Hotel opened in 1884 near Diamond Creek and was in operation until 1889. That year Louis Boucher opened a larger hotel at Dripping Springs. John Hance opened his ranch near Grandview to tourists in 1886 only to sell it nine years later in order to start a long career as a Grand Canyon guide (in 1896 he also became local postmaster).

William Wallace Bass opened a tent house campground in 1890. Bass Camp had a small central building with common facilities such as a kitchen, dining room, and sitting room inside. Rates were $2.50 a day ($81.43 as of 2024), and the complex was 20 miles (30 km) west of the Grand Canyon Railway's Bass Station (Ash Fort). Bass also built the stage coach road that he used to carry his patrons from the train station to his hotel. A second Bass Camp was built along the Shinumo Creek drainage.[24]

The Grand Canyon Hotel Company was incorporated in 1892 and charged with building services along the stage route to the canyon.[27] In 1896 the same man who bought Hance's Grandview ranch opened Bright Angel Hotel in Grand Canyon Village.[27] The Cameron Hotel opened in 1903, and its owner started to charge a toll to use the Bright Angel Trail.[27]

Things changed in 1905 when the luxury El Tovar Hotel opened within steps of the Grand Canyon Railway's terminus.[22] El Tovar was named for Don Pedro de Tovar who tradition says is the Spaniard who learned about the canyon from Hopis and told Coronado. Charles Whittlesey designed the arts and crafts-styled rustic hotel complex, which was built with logs from Oregon and local stone at a cost of $250,000 for the hotel ($8,140,000 as of 2024) and another $50,000 for the stables ($1,630,000 as of 2024).[27] El Tovar was owned by Santa Fe Railroad and operated by its chief concessionaire, the Fred Harvey Company.

Fred Harvey hired Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter in 1902 as company architect. She was responsible for five buildings at the Grand Canyon: Hopi House (1905), Lookout Studio (1914), Hermit's Rest (1914), Desert View Watchtower (1932), and Bright Angel Lodge (1935).[3] She stayed with the company until her retirement in 1948.

A cable car system spanning the Colorado went into operation at Rust's Camp, located near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek, in 1907. Former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt stayed at the camp in 1913. That, along with the fact that while president he declared Grand Canyon a U.S. National Monument in 1908, led to the camp being renamed Roosevelt's Camp. In 1922 the National Park Service gave the facility its current name, Phantom Ranch.[27]

In 1917 on the North Rim, W.W. Wylie built accommodations at Bright Angel Point.[22] The Grand Canyon Lodge opened on the North Rim in 1928. Built by a subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad called the Utah Parks Company, the lodge was designed by Gilbert Stanley Underwood who was also the architect for the Ahwahnee Hotel in California's Yosemite Valley. Much of the lodge was destroyed by fire in the winter of 1932, and a rebuilt lodge did not open until 1937. The facility is managed by TW Recreation Services.[24] Bright Angel Lodge and the Auto Camp Lodge opened in 1935 on the South Rim.

Activities

New hiking trails, along old Indian trails, were established during this time as well. The world-famous mule rides down Bright Angel Trail were mass-marketed by the El Tovar Hotel. By the early 1990s, 20,000 people per year made the journey into the canyon by mule, 800,000 by hiking, 22,000 passed through the canyon by raft, and another 700,000 tourists fly over it in air tours (fixed-wing aircraft and helicopter). Overflights were limited to a narrow corridor in 1956 after two planes crashed, killing all on board. In 1991 nearly 400 search and rescues were performed, mostly for unprepared hikers who suffered from heat exhaustion and dehydration while ascending from the canyon (normal exhaustion and injured ankles are also common in rescuees).[28] An IMAX theater just outside the park shows a reenactment of the Powell Expedition.

The Kolb Brothers, Emery and Ellsworth, built a photographic studio on the South Rim at the trailhead of Bright Angel Trail in 1904. Hikers and mule caravans intent on descending down the canyon would stop at the Kolb Studio to have their photos taken. The Kolb Brothers processed the prints before their customers returned to the rim. Using the newly invented Pathé Bray camera in 1911–12, they became the first to make a motion picture of a river trip through the canyon that itself was only the eighth such successful journey. From 1915 to 1975 the film they produced was shown twice a day to tourists with Emery Kolb at first narrating in person and later through tape (a feud with Fred Harvey prevented pre-1915 showings).[29]

Protection efforts

By the late 19th century, the conservation movement was increasing national interest in preserving natural wonders like the Grand Canyon. National Parks in Yellowstone and around Yosemite Valley were established by the early 1890s. U.S. Senator Benjamin Harrison introduced a bill in 1887 to establish a national park at the Grand Canyon.[18] The bill died in committee, but on February 20, 1893, Harrison (then President of the United States) declared the Grand Canyon to be a National Forest Preserve.[30] Mining and logging were allowed, but the designation did offer some protection.[18]

President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Grand Canyon in 1903.[22] An avid outdoorsman and staunch conservationist, he established the Grand Canyon Game Preserve on November 28, 1906.[30] Livestock grazing was reduced, but predators such as mountain lions, eagles, and wolves were eradicated. Roosevelt added adjacent national forest lands and re-designated the preserve a U.S. National Monument on January 11, 1908.[30] Opponents, such as holders of land and mining claims, blocked efforts to reclassify the monument as a National Park for 11 years. Grand Canyon National Park was finally established as the 17th U.S. National Park by an Act of Congress signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on February 26, 1919.[30] The National Park Service declared the Fred Harvey Company to the official park concessionaire in 1920 and bought William Wallace Bass out of business.

An area of almost 310 square miles (800 km²) adjacent to the park was designated as a second Grand Canyon National Monument on December 22, 1932.[31] Marble Canyon National Monument was established on January 20, 1969, and covered about 41 square miles (105 km²).[31] An act signed by President Gerald Ford on January 3, 1975, doubled the size of Grand Canyon National Park by merging these adjacent national monuments and other federal land into it. That same act gave Havasu Canyon back to the Havasupai tribe.[22] From that point, the park stretched along a 278-mile (447 km) segment of the Colorado River from the southern border of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area to the eastern boundary of Lake Mead National Recreation Area.[31] Grand Canyon National Park was designated a World Heritage Site on October 24, 1979.[32]

In 1935, Hoover Dam started to impound Lake Mead south of the canyon.[16] Conservationists lost a battle to save upstream Glen Canyon from becoming a reservoir. The Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1966 to control flooding and to provide water and hydroelectric power.[33] Seasonal variations of high flow and flooding in the spring and low flow in summer have been replaced by a much more regulated system. The much more controlled Colorado has a dramatically reduced sediment load, which starves beaches and sand bars. In addition, clearer water allows significant algae growth to occur on the riverbed, giving the river a green color.

With the advent of commercial flights, the Grand Canyon has been a popular site for aircraft overflights. However, a series of accidents resulted in the Overflights Act of 1987 by the United States Congress, which banned flights below the rim and created flight-free zones.[34] The tourist flights over the canyon have also created a noise problem, so the number of flights over the park has been restricted.

In 2008, the Grand Canyon Railway[35] and their parent company, Xanterra, decided to use only EMD f40ph diesel locomotives as their main motive power for their trackage, since they felt that their steam locomotives, as well as their Alco fa units, gave the environment more visible smoke. Not only that, but the steamers burn more oil than an average diesel unit, hence they can also be more pricey to operate and maintain. However, after a variety of formers protested to the GCR to bring back steam operations,[36] the GCR decided to bring back steam operations, as they converted both of their operational steamers, 29 and 4960, to burn recycled waste vegetable oil collected from nearby restaurants by third-party suppliers.[37]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Geologist Jules Marcou of the Pacific Railroad Survey made the first geologic observations of the canyon in 1856.[17]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Tufts 1998, p. 12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 396

- 1 2 3 4 American Park Network

- ↑ O'Connor 1992, p. 16

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Castañeda 1596

- 1 2 Ranney, Wayne (April 2014). "A pre–21st century history of ideas on the origin of the Grand Canyon". Geosphere. 10 (2): 233–242. Bibcode:2014Geosp..10..233R. doi:10.1130/ges00960.1.

- ↑ Herbert E. Bolton (1964). Coronado: Knight of Pueblos and Plains. Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, pp. 54, 139–140.

- ↑ Page Stegner (1994). Grand Canyon, The Great Abyss. HarperCollins. p. 25. ISBN 0-06-258564-9.

- ↑ Pattie, James Ohio; Thwaites, Reuben Gold; Flint, Timothy (1905). The Personal Narrative of James O. Pattie, of Kentucky: During an Expedition from St. Louis, Through the Vast Regions Between that Place and the Pacific Ocean, and Thence Back Through the City of Mexico to Vera Cruz, During Journeyings of Six Years, Etc. Vol. 18. Chicago: A.H. Clark. p. 14.

- ↑ Hamblin, Jacob; Little, James A. (1971). Jacob Hamblin, a Narrative of His Personal Experience, as a Frontiersman, Missionary to the Indians and Explorer, Disclosing Interpositions of Providence, Severe Privations, Perilous Situations and Remarkable Escapes. Ayer Publishing. p. 136. ISBN 0-8369-5899-3.

- ↑ Ward, Greg (2003). The rough guide to the Grand Canyon. Rough Guides. pp. 113, 251. ISBN 1-84353-052-X.

- ↑ Bonsal, Stephen (1912). Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a Pioneer in the Path of Empire, 1822–1903. New York: G. P. Putnam's sons. p. 208.

- ↑ Dodge, Bertha Sanford (1980). The Road West: Saga of the 35th Parallel (1st ed.). University of New Mexico Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-8263-0526-1.

- ↑ Rules and Regulations, Grand Canyon National Park. NPS contributors. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. 1920. p. 9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Ives, Joseph C.; Newberry, John Strong (1861). Report Upon the Colorado River of the West: Explored in 1857 and 1858. United States Army Corps of Engineers. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 110.

- 1 2 Harris & Tuttle 1997, p. 7

- ↑ Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 396.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 397

- ↑ O'Connor 1992, p. 17

- ↑ O'Connor 1992, p. 19

- ↑ O'Connor 1992, p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Tufts 1998, p. 13

- 1 2 3 Lohman, S. W. (1981). "Late Arrivals" (PDF). The Geologic Story of Colorado National Monument. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-05-03. (adapted public domain text)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 O'Connor 1992, p. 30

- 1 2 Green, Mark; Farber, R; Lien, N; Gebhart, K; Molenar, J; Iyer, H; Eatough, D (November 1, 2005). "The effects of scrubber installation at the Navajo Generating Station on particulate sulfur and visibility levels in the Grand Canyon". Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 55 (11): 1675–1682. Bibcode:2005JAWMA..55.1675G. doi:10.1080/10473289.2005.10464759. PMID 16350365. S2CID 31615461.

- ↑ "EPA Debates Controls For Grand Canyon Air". National Parks. 66 (7/8): 11. July 1991.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Connor 1992, p. 31

- ↑ Reference for the whole paragraph: O'Connor 1992, p. 32

- ↑ O'Connor 1992, pp. 18, 32

- 1 2 3 4 "Records of Grand Canyon National Park, AZ". Records of the National Park Service [NPS]. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. pp. 79.7.7. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- 1 2 3 Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 395

- ↑ "Grand Canyon National Park". About.com. Archived from the original on 2006-04-17. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ Colorado River Basin water management: evaluating and adjusting to hydroclimatic variability. National Research Council, Water Science and Technology Board. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 2007. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-309-10524-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "The National Parks Overflight Act of 1987 Public Law 100-91" (PDF). 1987. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ↑ "Grand Canyon Railway | Grand Canyon Railway & Hotel". Grand Canyon Railway. Retrieved 2021-02-12.

- ↑ Grand Canyon Railway Steam Program Tribute, archived from the original on 2023-05-15, retrieved 2021-02-12

- ↑ "Grand Canyon Railway Steam - Powered by WVO - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2021-02-12.

Bibliography

- Pedro de Castañeda of Najera (1990) [1596]. The Journey of Coronado, 1540–1542 [Originally published as: Account of the Expedition to Cibola which took place in the year 1540]. Translated by George Parker Winship. Seville (orig.); Golden, Colorado (trans.): Fulcrum Publishing. pp. 115–117. ISBN 1-55591-066-1.

- Harris, Ann G.; Tuttle, Esther; Tuttle, Sherwood D. (1997). Geology of National Parks (5th ed.). Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing. ISBN 0-7872-5353-7.

- Kiver, Eugene P.; Harris, David V. (1999). Geology of U.S. Parklands (5th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-33218-6.

- O'Connor, Letitia Burns (1992). The Grand Canyon. Los Angeles: Perpetua Press. pp. 16–19, 30–32. ISBN 0-88363-969-6.

- Tufts, Lorraine Salem (1998). Secrets in The Grand Canyon, Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks (3rd ed.). North Palm Beach, Florida: National Photographic Collections. ISBN 0-9620255-3-4.

This article incorporates public domain material from American Indians at Grand Canyon – Past and Present. National Park Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from American Indians at Grand Canyon – Past and Present. National Park Service. This article incorporates public domain material from When and Why Did Grand Canyon Become a National Park?. National Park Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from When and Why Did Grand Canyon Become a National Park?. National Park Service.

Further reading

- Rudd, Connie (1990). Grand Canyon The Continuing Story. KC Publishing. ISBN 0-88714-046-7.

External links

- Grand Canyon Railway official website

- American Park Network: Grand Canyon History

- usparks.about.com – Grand Canyon National Park Archived 2006-04-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Grand Canyon North Rim

- Diane Grua, "Saving the Life Work of Two Daring Grand Canyon Photographers: The Emery Kolb Collection at Northern Arizona University's Cline Library", Annotation, December 1998

- Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park, U.S. National Park Service