The history of the British Army's Special Air Service (SAS) regiment of the British Army begins with its formation during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War, and continues to the present day. It includes its early operations in North Africa, the Greek Islands, and the Invasion of Italy. The Special Air Service then returned to the United Kingdom and was formed into a brigade with two British, two French and one Belgian regiment, and went on to conduct operations in France, Italy again, the Low Countries and finally into Germany.

After the war, the SAS was disbanded only to be reformed as a Territorial Army regiment, which then led to the formation of the regular army 22 SAS Regiment. The SAS has taken part in most of the United Kingdom's wars since then.[1]

Second World War

The Special Air Service began life in July 1941, during the Second World War, from an unorthodox idea and plan by Lieutenant David Stirling (of the Scots Guards) who was serving with No. 8 (Guards) Commando. His idea was for small teams of parachute-trained soldiers to operate behind enemy lines to gain intelligence, destroy enemy aircraft, and attack their supply and reinforcement routes. Following a meeting with Major-General Neil Ritchie, the Deputy Chief of Staff, he was granted an appointment with the new Commander-in-Chief Middle East, General Claude Auchinleck. Auchinleck liked the plan and it was endorsed by the Army High Command. At that time, there was already a deception organisation in the Middle East area, which wished to create a phantom airborne brigade to act as a threat to enemy planning. This deception unit was named K Detachment Special Air Service Brigade, and thus Stirling's unit was designated L Detachment Special Air Service Brigade.

The force initially consisted of five officers and 60 other ranks.[2] Following extensive training at Kabrit camp, by the River Nile, L Detachment undertook its first operation, Operation Squatter. This parachute drop behind Axis lines was launched in support of Operation Crusader. During the night of 16/17 November 1941, L Detachment attacked airfields at Gazala and Timimi. Due to Axis resistance and adverse weather conditions, the mission was a disaster with 22 men killed or captured (one-third of the men).[3] Given a second opportunity L Detachment recruited men from Layforce Commando, which was in the process of disbanding. Their second mission was more successful; transported by the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), they attacked three airfields in Libya, destroying 60 aircraft without loss.[3]

In October 1941, David Stirling had asked the men to come up with ideas for insignia designs for the new unit. Bob Tait, who had accompanied Stirling on the first raid, produced the winning entry: the flaming sword of Excalibur, the legendary weapon of King Arthur. This motif would later be misinterpreted as a winged dagger. In regard to mottoes, "Strike and Destroy" was rejected as being too blunt. "Descend to Ascend" seemed inappropriate since parachuting was no longer the primary method of transport. Finally, Stirling settled on "Who Dares Wins," which seemed to strike the right balance of valour and confidence. SAS pattern parachute wings, designed by Lieutenant Jock Lewes and depicted the wings of a scarab beetle with a parachute. The wings were to be worn the right shoulder upon completion of parachute training. After three missions, they were worn on the left breast above medal ribbons. The wings, Stirling noted, "Were treated as medals in their own right."[4]

1942

Their first mission in 1942 was an attack on Bouerat. Transported by the LRDG, they caused severe damage to the harbour, petrol tanks and storage facilities.[5] This was followed up in March by a raid on Benghazi harbour with limited success although the raiding party did damage 15 aircraft at Al-Berka.[5] The June 1942 Crete airfield raids at Heraklion, Kasteli, Tympaki and Maleme significant damage was caused but of the attacking force at Heraklion only Major George Jellicoe returned.[6] In July 1942, Stirling commanded a joint SAS/LRDG patrol that carried out raids at Fuka and Mersa Matruh airfields destroying 30 aircraft.[7]

September 1942 was a busy month for the SAS. They were renamed 1st SAS Regiment and consisted of four British squadrons, one Free French Squadron, one Greek Squadron, and the Special Boat Section (SBS).[8]

Operations they took part in included Operation Agreement and the diversionary raid Operation Bigamy. Bigamy, which was led by Stirling and supported by the LRDG, was an attempt at a large-scale raid on Benghazi to destroy the harbour and storage facilities and to attack the airfields at Benina and Barce.[9] However, they were discovered after a clash at a roadblock. With the element of surprise lost, Stirling decided not to go ahead with the attack and ordered a withdrawal.[9] Agreement was a joint operation by the SAS and the LRDG who had to seize an inlet at Mersa Sciausc for the main force to land by sea. The SAS successfully evaded enemy defences assisted by German-speaking members of the Special Interrogation Group and captured Mersa Sciausc. The main landing failed, being met by heavy machine gun fire forcing the landing force and the SAS/LRDG force to surrender.[10] Operation Anglo, a raid on two airfields on the island of Rhodes, from which only two men returned. Destroying three aircraft, a fuel dump and numerous buildings, the surviving SBS men had to hide in the countryside for four days before they could reach the waiting submarine.[11][Note 1]

1943

David Stirling, who was by that time sometimes referred to as the "Phantom Major" by the Germans, was captured in January 1943 in the Gabès area by a special anti-SAS unit set up by the Germans.[13] He spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war, escaping numerous times before being moved to the supposedly 'escape proof' Colditz Castle.[13] He was replaced as commander 1st SAS by Paddy Mayne.[14] In April 1943, the 1st SAS was reorganised into the Special Raiding Squadron under the command of Mayne and the Special Boat Squadron under the command of George Jellicoe.[15] The Special Boat Squadron operated in the Aegean and the Balkans for the remainder of the war and was disbanded in 1945.

The Special Raiding Squadron spearheaded the invasion of Sicily Operation Husky and played more of a commando role raiding the Italian coastline, from which they suffered heavy losses at Termoli.[13] After Sicily they went on to serve in Italy with the newly formed 2nd SAS, a unit which had been formed in Algeria in May 1943 by Stirling's older brother Lieutenant Colonel Bill Stirling.[13]

The 2nd SAS had already taken part in operations in support of the Allied landings in Sicily. Operation Narcissus was a raid by 40 members of 2nd SAS on a lighthouse on the southeast coast of Sicily. The team landed on 10 July with the mission of capturing the lighthouse and the surrounding high ground. Operation Chestnut involved two teams of ten men each, parachuted into northern Sicily on the night of 12 July, to disrupt communications, transport and the enemy in general.

On mainland Italy they were involved in Operation Begonia which was the airborne counterpart to the amphibious Operation Jonquil. From 2 to 6 October 1943, 61 men were parachuted between Ancona and Pescara. The object was to locate escaped prisoners of war in the interior and muster them on beach locations for extraction. Begonia involved the interior parachute drop by 2nd SAS. Jonquil entailed four seaborne beach parties from 2nd SAS with the Free French SAS Squadron as protection. Operation Candytuft was a raid by 2nd SAS on 27 October. Inserted by boat on Italy's east coast between Ancona and Pescara, they were to destroy rail bridges and disrupt rear areas.

Near the end of the year the Special Raiding Squadron reverted to their former title 1st SAS and together with 2nd SAS were withdrawn from Italy and placed under command of the 1st Airborne Division.[16]

1944

In March 1944, the 1st and 2nd SAS Regiments returned to the United Kingdom and joined a newly formed the SAS Brigade of the Army Air Corps. The other units in the Brigade were the French 3rd and 4th SAS, the Belgian 5th SAS and F Squadron which was responsible for signals and communications, the brigade commander was Brigadier Roderick McLeod.[16] The brigade was ordered to swap their beige SAS berets for the maroon parachute beret and given shoulder titles for 1, 2, 3 and 4 SAS in the Airborne colours. The French and Belgian regiments also wore the Airborne Pegasus arm badge.[17] The brigade now entered a period of training for their participation in the Normandy Invasion. They were prevented from conducting operations until after the start of the invasion by 21st Army Group. Their task was then to stop German reinforcements reaching the front line,[18] by being parachuted behind the lines to assist the French Resistance.[19]

In support of the invasion 144 men of 1st SAS took part in Operation Houndsworth between June and September, in the area of Lyon, Chalon-sur-Saône, Dijon, Le Creusot and Paris.[18] At the same time, 56 men of 1st SAS also took part in Operation Bulbasket in the Poitiers area. They did have some success before being betrayed. Surrounded by a large German force, they were forced to disperse; later, it was discovered that 36 men were missing and that 32 of them had been captured and executed by the Germans.[18]

In mid-June, 178 men of the French SAS and 3,000 members of the French resistance took part in Operation Dingson. However, they were forced to disperse after their camp was attacked by the Germans.[18] The French SAS were also involved in Operation Cooney, Operation Samwest and Operation Lost during the same period.[20]

In August, 91 men from the 1st SAS were involved in Operation Loyton. The team had the misfortune to land in the Vosges Mountains at a time when the Germans were preparing to defend the Belfort Gap. As a result, the Germans harried the team. The team also suffered from poor weather that prevented aerial resupply. Eventually, they broke into smaller groups to return to their own lines. During the escape, 31 men were captured and executed by the Germans.

Also in August, men from 2nd SAS operated from forest bases in the Rennes area in conjunction with the resistance. Air resupply was plentiful and the resistance cooperated, which resulted in carnage. The 2nd SAS operated from the Loire through to the forests of Darney to Belfort in just under six weeks.[21]

Near the end of the year, men from 2nd SAS were parachuted into Italy to work with the Italian resistance in Operation Tombola, where they remained until Italy was liberated.[22] At one point, four groups were active deep behind enemy lines laying waste to airfields, attacking convoys and derailing trains. Towards the end of the campaign, Italian guerrillas and escaped Russian prisoners were enlisted into an 'Allied SAS Battalion' which struck at the German main lines of communications.[23]

1945

In March the former Chindit commander, Brigadier Mike Calvert took over command of the brigade.[22] The 3rd and 4th SAS were involved in Operation Amherst in April. The operation began with the drop of 700 men on the night of 7 April. The teams spread out to capture and protect key facilities from the Germans. They encountered Bergen-Belsen on 15 April 1945.[24]

Still in Italy in Operation Tombola, Major Roy Farran and 2nd SAS carried out a raid on a German Corps headquarters in the Po Valley, which succeeded in killing the corps chief of staff.[21]

The Second World War in Europe ended on 8 May and by that time the SAS brigade had suffered 330 casualties, but it had killed or wounded 7,733 and captured 23,000 of their enemies.[22] Later the same month 1st and 2nd SAS were sent to Norway to disarm the 300,000-strong German garrison and 5th SAS were in Denmark and Germany on counter-intelligence operations.[22] The brigade was dismantled soon afterwards. In September, the Belgian 5th SAS were handed over to the reformed Belgian Army. On 1 October the 3rd and 4th French SAS were handed over to the French Army and on 8 October the British 1st and 2nd SAS regiments were disbanded.[19]

Malaya

At the end of the war, the British Government could see no need for a SAS-type regiment, but in 1946 it was decided that there was a need for a long-term deep penetration commando or SAS unit. A new SAS regiment was raised as part of the Territorial Army.[25] The regiment chosen to take on the SAS mantle was the Artists Rifles.[25] The new 21 SAS Regiment came into existence on 1 January 1947 and took over the Artists Rifles headquarters at Dukes Road, Euston.[26]

In 1950 the SAS raised a squadron to fight in the Korean War. After three months of training, they were informed that the squadron would not, after all, be needed in Korea, and instead were sent to serve in the Malayan Emergency. On arrival in Malaya the squadron came under the command of the wartime SAS Brigade commander, Mike Calvert. They became B Squadron, Malayan Scouts (SAS),[27] the other units were A Squadron, which had been formed from 100 local volunteers mostly ex Second World War SAS and Chindits and C Squadron formed from volunteers from Rhodesia, the so-called 'Happy Hundred'. By 1956 the Regiment had been enlarged to five squadrons with the addition of D Squadron and the Parachute Regiment Squadron.[28][29] After three years service the Rhodesians returned home and were replaced by a New Zealand squadron.[30]

A Squadron were based at Ipoh while B and C Squadrons were at Johore. During training, they pioneered techniques of resupply by helicopter and also set up the "Hearts and Minds" campaign to win over the locals with medical teams going from village to village treating the sick. With the aid of Iban trackers from Borneo they became experts at surviving in the jungle.[31] In 1951 the Malayan Scouts (SAS) had successfully recruited enough men to form a regimental headquarters, a headquarters squadron and four operational squadrons with over 900 men.[32] The regiment was tasked to seek, find, fix and then destroy the terrorists and prevent their infiltration into protected areas. Their tactics would be long-range patrols, ambush and tracking of the terrorists to their bases.[32] The SAS troops trained and acquired skills in treejumping, which involved parachuting into the thick jungle canopy and letting the parachute catch on the branches; brought to a halt, the parachutist then cut himself free and lowered himself to the ground by rope.[31] Using inflatable boats for river patrolling, jungle fighting techniques, psychological warfare and booby trapping terrorist supplies.[32] Calvert was invalided back to the United Kingdom in 1951 and replaced by Lieutenant-Colonel John Sloane.[31]

In February 1951, 54 men from B Squadron carried out the first parachute drop in the campaign in Operation Helsby, which was a major offensive in the River Perak–Belum valley, just south of the Thai border.[33]

The need for a regular army SAS regiment had been recognised, and so the Malayan Scouts (SAS) were renamed 22 SAS Regiment and formally added to the Army List in 1952.[34] However B Squadron was disbanded, leaving just A and D Squadrons in service.[35][36]

Oman and Borneo

In 1958 the SAS got a new commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Anthony Deane-Drummond.[37] The Malayan Emergency was winding down, so the SAS dispatched two squadrons from Malaya to assist in Oman. In January 1959, A Squadron defeated a large Guerrilla force on the Sabrina plateau. This was a victory that was kept from the public due to political and military sensitivities.[38]

After Oman, 22 SAS Regiment were recalled to the United Kingdom, the first time the regiment had served there since its formation. The SAS were initially barracked in Malvern Worcestershire before moving to Hereford in 1960.[37] Just prior to this, the third SAS regiment was formed and like 21 SAS was part of the Territorial Army. 23 SAS Regiment was formed by the renaming of the Joint Reserve Reconnaissance Unit, which itself had succeeded M.I.9 via a series of units (POW Rescue, Recovery and Interrogation Unit, Intelligence School 9 and the Joint Reserve POW Intelligence Organisation). Behind this change was the understanding that passive networks of escape lines had little place in the Cold War world and henceforth personnel behind the lines would be rescued by specially trained units.[39]

The regiment was sent to Borneo for the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, where they adopted the tactics of patrolling up to 20 kilometres (12 mi) over the Indonesian border and used local tribesman for intelligence gathering.[38] The troops at times lived in the indigenous tribes' villages for five months thereby gaining their trust. This involved showing respect for the Headman, giving gifts and providing medical treatment for the sick.[40]

In December 1963, the SAS went onto the offensive, now under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Woodhouse, adopting a "shoot and scoot" policy to keep SAS casualties to a minimum.[41] They were augmented by the adding to their strength of the Guards Independent Parachute Company and later the Gurkha Independent Parachute Company.[42] In 1964 Operation Claret was initiated, with soldiers selected from the infantry regiments in-theatre, placed under SAS command and known as "Killer Groups". These groups would cross the border and penetrate up to 18 kilometres (11 mi) disrupting the Indonesian Army build-up, forcing the Indonesians to move away from the border.[41] Reconnaissance patrols were used to enter enemy territory to identify supply routes, enemy locations and enemy boat traffic. Captain Robin Letts was awarded the Military Cross for his role in leading a reconnaissance patrol which successfully ambushed the enemy near Babang Baba in April 1965.[43] The Borneo campaign cost the British 59 killed 123 wounded compared to the Indonesian 600 dead.[41] In 1964 B Squadron was re-formed from a combination of former members still with the Regiment and new recruits.[44]

The SAS returned to Oman in 1970. The Marxist-controlled South Yemen government were supporting an insurgency in the Dhofar region that became known as the Dhofar Rebellion.[41] Operating under the umbrella of a British Army Training Team (BATT), the SAS recruited, trained and commanded the local Firquts. Firquts were local tribesmen and recently surrendered enemy soldiers. This new campaign ended shortly after the Battle of Mirbat in 1972, when a small SAS force and Firquts defeated 250 Adoo guerrillas.

Northern Ireland

In 1969 D Squadron, 22 SAS deployed to Northern Ireland for just over a month. The SAS returned in 1972 when small numbers of men were involved in intelligence gathering. The first squadron fully committed to the province was in 1976 and by 1977 two squadrons were operating in Northern Ireland.[45] These squadrons used well-armed covert patrols in unmarked civilian cars. Within a year four terrorists had been killed or captured and another six forced to move south into the Republic.[45] Members of the SAS are also believed to have served in the 14 Intelligence Company based in Northern Ireland.[46]

The first operation attributed to the SAS was the arrest of Sean McKenna on 12 March 1975. McKenna claims he was sleeping in a house just south of the Irish border when he was woken in the night by two armed men and forced across the border, while the SAS claimed he was found wandering in a field drunk.[47] Their second operation was on 15 April 1976 with the arrest and killing of Peter Cleary. Cleary, an IRA staff officer, was detained by five soldiers in a field while waiting for a helicopter to land. While four men guided the aircraft in, Cleary started to struggle with his guard, attempted to seize his rifle and was shot.[48]

The SAS returned to Northern Ireland in force in 1976, operating throughout the province. In January 1977 Seamus Harvey, armed with a shotgun, was killed during a SAS ambush.[49] On 21 June, six men from G Squadron ambushed four IRA men planting a bomb at a government building; three IRA members were shot and killed but their driver managed to escape.[50] On 10 July 1978, John Boyle, a sixteen-year-old Catholic, was exploring an old graveyard near his family's farm in County Antrim when he discovered an arms cache. He told his father, who passed on the information to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). The next morning Boyle decided to see if the guns had been removed and was shot dead by two SAS soldiers who had been waiting undercover.[51] In 1976 Newsweek also reported that eight SAS men had been arrested in the Republic of Ireland supposedly as a result of a navigational error. It was later revealed that they had been in pursuit of a Provisional Irish Republican Army unit.[45]

The SAS's early successes led to increasing paranoia within Republican circles, as the PIRA hunted for informers they felt certain were in their midst.[52] On 2 May 1980 Captain Herbert Westmacott became the highest-ranking member of the SAS to be killed in Northern Ireland.[53] He was in command of an eight-man plain clothes SAS patrol that had been alerted by the Royal Ulster Constabulary that an IRA gun team had taken over a house in Belfast.[54] A car carrying three SAS men went to the rear of the house, and another car carrying five SAS men went to the front of the house.[55] As the SAS arrived at the front of the house the IRA unit opened fire with an M60 machine gun, hitting Captain Westmacott in the head and shoulder, killing him instantly.[55] The remaining SAS men at the front returned fire, but were forced to withdraw.[54][55] One member of the IRA team was apprehended by the SAS at the rear of the house, preparing the unit's escape in a transit van, while the other three IRA members remained inside the house.[56] More members of the security forces were deployed to the scene, and after a brief siege, the remaining members of the IRA unit surrendered.[54] After his death, Westmacott was posthumously awarded the Military Cross for gallantry in Northern Ireland during the period 1 February 1980 to 30 April 1980.[57] Some sources say that the terrorists waved a white flag before the siege in an attempt to trick the SAS patrol into thinking they were surrendering.[58]

The SAS Regiment increased their operational focus on Northern Ireland, with a small element known as the Ulster Troop that were permanently stationed in Northern Ireland to provide specialist support to the British Army and RUC. The troop consisted of around 20 operators and associated support personnel, serving on a rotational basis. For larger pre-planned operations, Ulster Troop was reinforced by SAS personnel, often in small 2- or 3-man teams from the Special Projects Team. From 1980, the Troop served twelve-month tours instead of six-month tours, as it was felt that longer deployments allowed the operators to develop and maintain a better understanding of the key factions and senior PIRA terrorists. Surveillance became an important aspect of the Troop, with 14 Intelligence & Security Company (commonly known as "The Det") often carrying out surveillance missions that led to SAS ambushes.[52]

On 4 December 1983, a SAS patrol found two IRA gunmen who were both armed, one with an Armalite rifle and the other a shotgun. These two men did not respond when challenged so the patrol opened fire, killing the two men. A third man who escaped in a car was believed to have been wounded.[59]

The SAS conducted a large number of operations officially called "OP/React": acting on information provided by a range of sources, including informers and technical intelligence. The Det, MI5 and the RUC's E4a surveillance unit would target and track ASU terrorists until a terrorist operation was thought to be imminent; at that point, the SAS were handed control and would plan an arrest operation, and if the terrorists were armed and did not comply they would be engaged. In December 1984, a SAS team killed two ASU terrorists who were attempting to assassinate a reserve soldier outside a hospital he worked at. In February 1985, three SAS operators killed three ASU terrorists in Strabane. The terrorists were tasked with attacking a RUC Land Rover with anti-tank grenades, but having failed to find a suitable target they were visiting a weapons cache to store their weapons. There was considerable media speculation during 'the Troubles' and allegations of so-called "shoot-to-kill" policy by the SAS; the allegations mainly focus on whether a terrorist could have been captured alive rather than killed. The PIRA never took prisoners except for the worst intentions and after the 1980 death of Captain Westmacott and the death of a SAS member in December 1984, the Regiment appeared to adopt an unofficial policy of what Mark Urban quoted SAS sources as calling "Big boys' games- big boys' rules": if you're an armed terrorist you can expect no quarter to be given.[60]

On 8 May 1987, the SAS conducted Operation Judy which resulted in the IRA/ASU[61] suffering its worst single loss of men, when eight men were killed by the SAS while attempting to attack the Loughgall police station. The SAS had been informed of the attack and 24 men waited in ambush positions around and inside the police station. They opened fire when the armed IRA unit approached the station with a 200 pounds (91 kg) bomb, its fuse lit, in the bucket of a hijacked JCB digger. A civilian passing the incident was also killed by SAS fire.[62]

In the late 1980s the IRA started to move operations to the European mainland. Operation Flavius in March 1988 was a SAS operation in Gibraltar in which three PIRA volunteers, Seán Savage, Daniel McCann and Mairéad Farrell, were killed. All three had conspired to detonate a car bomb where a military band assembled for the weekly changing of the guard at the Governor's residence.[63] However, eyewitnesses to the shooting in Gibraltar stated in the Thames Television documentary Death On The Rock that they believed McCann and Farrell were shot with their hands up.[64] Another eyewitness said that Savage was shot in the back.[65] Two witnesses claimed to have seen the IRA members "finished off" on the ground.[66] The following day, Sir Geoffrey Howe, the British foreign secretary, made a statement to the House of Commons regarding the shootings, in which he informed the house that the IRA members were unarmed, and that the car one of them had parked in the assembly area did not contain an explosive device.[67] Families of the three killed in Gibraltar brought a case against the British government to the European Court of Human Rights.[68] The ECtHR considered whether the shooting was disproportionate to the aims to be achieved by the state in apprehending the suspects and defending the citizens of Gibraltar from unlawful violence. The court found a violation of article 2: the killing of the three IRA members did not constitute a use of force which was "absolutely necessary" as proscribed by Article 2-2. It also held that, although there had been no conspiracy, the planning and control of the SAS operation was so flawed as to make the use of lethal force almost inevitable.[68]

In Germany, in 1989 the German security forces discovered a SAS unit operating there without the permission of the German government.[69]

In 1991 three IRA men were killed by the SAS. The IRA men were on their way to kill an Ulster Defence Regiment soldier who lived in Coagh, when they were ambushed.[70] These three and another seven brought the total number of IRA men killed by the SAS in the 1990s to 11.[71]

Counter terrorist wing

In the early 1970s, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Edward Heath asked the Ministry of Defence to prepare for any possible terrorist attack similar to the 1972 Munich massacre at the Munich Olympic Games and ordered that the SAS Counter Revolutionary Warfare (CRW) wing be established.[72] In a little over a month the first 20-man SAS Counter Terrorist (CT) unit was ready to respond to any potential incident within the UK or abroad. Originally, it was known as the Pagoda Team (named after Operation Pagoda, the codename for the development of the SAS CT capability) and was initially composed of members from all squadrons, particularly members who had experience in the Regiment's Bodyguarding Cell, but was soon placed under the control of the CRW.[73] Once the wing had been established each squadron would in turn rotate through counter-terrorist training. The training included live firing exercises, hostage rescue and siege breaking. It was reported that during CRW training each soldier would expend 100,000 pistol rounds and would return to the CRW role on average every 16 months.[72] The CRW initially consisted of a single SAS officer tasked with monitoring terrorism developments, but which was soon expanded and trimmed in size to a single troop strength; British technical experts developed a number of innovations for the team, including the first "flashbang" or "stun" grenade and the earliest examples of Frangible ammunition.[73]

Home operations

Their first home deployment came on 7 January 1975, when an Iranian armed with a replica pistol hijacked a British Airways BAC One-Eleven that landed at Stansted Airport. The hijacker was captured alive with no shots fired, the only casualty being a SAS soldier who was bitten by a police dog as he left the airliner.[73] The SAS was also deployed during the Balcombe Street Siege, where the Metropolitan Police had trapped a PIRA unit. Hearing on the BBC that the SAS were being deployed the PIRA men surrendered.[72]

Iranian Embassy siege

The Iranian Embassy Siege started at 11:30 on 30 April 1980 when a six-man team calling itself the 'Democratic Revolutionary Movement for the Liberation of Arabistan' (DRMLA) occupied the embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Prince's Gate, South Kensington in central London. When the group first stormed the building, 26 hostages were taken, but five were released over the following few days. On the sixth day of the siege, the kidnappers killed a hostage. This marked an escalation of the situation and prompted Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's decision to proceed with the rescue operation. The order to deploy the SAS was given, and B Squadron, the duty CRW squadron, were alerted. When the first hostage was shot, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, David McNee, passed a note signed by Thatcher to the Ministry of Defence, stating this was now a "military operation".[74] It was known as Operation Nimrod.[75]

The rescue mission started at 19:23, 5 May when the SAS assault troops at the front gained access to the embassy's first floor balcony via the roof. Another team assembled on the ground floor terrace entered via the rear of the embassy. After forcing entry, five of the six terrorists were killed. One of the hostages was also killed by the terrorists during the assault, which lasted 11 minutes. Scenes from outside the embassy were broadcast live on national television and soon rebroadcast around the world, creating fame and a reputation for the SAS.[74] Prior to the assault, few outside of the military special operations community even knew of the regiment's existence.[76]

Peterhead prison

On 28 September 1987 a riot in D Wing of Peterhead Prison resulted in prisoners taking over the building and taking a prison officer, 56-year-old Jackie Stuart, hostage. The rioters were serving life in prison for violent crimes. It was thought that they had nothing to lose and would not hesitate to make good on their threats to kill their hostage, who they had now taken up to the rafters of the Scottish prison. When negotiations broke down, the then Home Secretary Douglas Hurd dispatched the SAS to bring the riot to an end on 3 October. The CRW troops arrived by helicopter, landed on the roof and then abseiled into the prison proper. Armed only with pistols, batons and stun grenades they brought the riot to a swift closure.

War on Terror in the UK

In 2005 London was the target of two attacks on 7 July and 21 July. It was reported in Times that the SAS CRW played a role in the capture of three men suspected of taking part in the failed 21 July bomb attacks. The SAS CRW also provided expertise in explosive entry techniques to back up raids by police firearms officers. It was also reported that plain clothes SAS teams were monitoring airports and main railway stations to identify any security weaknesses and that they were using civilian helicopters and two small executive jets to move around the country.[77]

Following the bombings, a small forward element of the CRW was permanently deployed to the capital to provide immediate assistance to the Metropolitan Police Service in the event of a terrorist incident. This unit is supported by its own attached Ammunition technical officer trained in high-risk search and making safe car bombs and improvised explosive devices, along with a technical intelligence cell capable of sophisticated interception of all forms of communication. In particular, after 21 July bombings, several SAS elements trained in explosive methods of entry were dispatched to support the Metropolitan Police firearms unit, and were used to explosively breach two flats where would-be suicide bombers had taken refuge, the police fired CS gas into both premises and negotiated the surrender of all suspects.[78]

The police retain primacy and are the lead in the event of a terrorist attack on British soil, but the military will provide support if requested. If a situation is deemed to be outside the capabilities of police firearms units (such as a requirement for specialist breaching capabilities), the SAS will be called in under the Military Aid to the Civil Authorities legislation. Additionally, some categories of operation-such as the recapture of hijacked airlines or cruise ships, or the recovery of nuclear or radioactive IEDs remain a military responsibility.[79]

The Telegraph reported on 4 June 2017 that following the Manchester Arena bombing in May 2017, small numbers of SAS soldiers supported police and accompanied officers on raids around the city. Following the London Bridge attack, a SAS unit nicknamed 'Blue Thunder' arrived after the attack had been ended by armed police. A Eurocopter AS365 N3 Dauphin helicopter landed on London Bridge carrying what a Whitehall source confirmed were carrying SAS troops.[80]

Overseas operations

Nations around the world particularly wanted a counter-terrorism capability like the SAS. The Ministry of Defence and Foreign and Commonwealth Office often loan out training teams from the Regiment, particularly to the Gulf States to train bodyguard teams now focused on CT. The Regiment has also had a long-standing association with the US Army's Delta Force, with the two units often having swapped techniques and tactics, as well as conducting joint training exercises in North America and Europe. Other nations' CT units developed close ties with the Regiment, including the Australian SAS, New Zealand SAS, GSG 9 and GIGN.[81]

The first documented action by the CRW Wing was assisting the West German counter-terrorism group GSG 9 at Mogadishu.[82] Eventually the CRW grew into full squadron strength and included its own support elements-Explosive Ordnance Disposal, search and combat dogs, medics and attached intelligence and targeting cell.[73]

Along with overseas training missions, the Regiment also sends small teams to act as observers and to provide advice or technical input if required at the scenes of terrorist and similar incidents worldwide.[83]

The Gambia

In August 1981 a 2-man SAS team was covertly deployed to The Gambia to help put down a coup.[84][85]

Colombian conflict

During the late 1980s members of the Regiment were dispatched to Colombia to train Colombian special operations forces in counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics operations. As of 2017, the training teams missions remain classified; rumours that SAS operators, with their US counterparts, accompanied Colombian forces on jungle operations, but this hasn't been confirmed.[73]

Waco siege

In 1993, SAS and Delta Force operators were deployed as observers in the Waco siege in Texas.[83]

Air France Flight 8969

In December 1994, the SAS were deployed as observers when Air France Flight 8969 was hijacked by GIA terrorists, the crisis was eventually resolved by GIGN.[83]

Japanese embassy hostage crisis

In early 1997, six members of the SAS were sent to Peru during the Japanese embassy hostage crisis due to diplomatic personnel being among the hostages and also to observe and advise Peruvian commandos in Operation Chavín de Huántar- the release of hostages by force.[86][87]

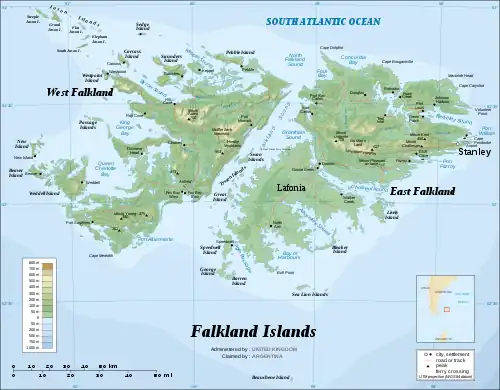

Falklands War

The Falklands War started after Argentina's occupation of the Falkland Islands on 2 April 1982. Brigadier Peter de la Billière the Director Special Forces and Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Rose, the Commander of 22 SAS Regiment, petitioned for the regiment to be included in the task force. Without waiting for official approval D Squadron, which was on standby for worldwide operations, departed on 5 April for Ascension Island.[88] They were followed by G Squadron on 20 April. As both squadrons sailed south the plans were for D Squadron to support operations to retake South Georgia while G Squadron would be responsible for the Falkland Islands.[88] By virtue of a 1981 transfer from A Squadron to G Squadron, John Thompson was the only one of the 55 SAS soldiers involved in the Iranian siege to also see action in the Falklands.[89]

South Georgia

Operation Paraquet was the code name for the first land to be liberated in the conflict. South Georgia is an island to the southeast of the Falkland Islands and one of the Falkland Islands Dependencies. In atrocious weather the SAS, SBS and Royal Marines forced the Argentinian garrison to surrender. On 22 April Westland Wessex helicopters landed a SAS unit on the Fortuna Glacier. This resulted in the loss of two of the helicopters, one on takeoff and one crashed into the glacier in almost zero visibility.[90] The SAS unit were defeated by the weather and terrain and had to be evacuated after only managing to cover 500 metres (1,600 ft) in five hours.[91]

The following night, a SBS section succeeded in landing by helicopter while Boat Troop and D Squadron SAS set out in five Gemini inflatable boats for the island. Two boats suffered engine failure with one crew being picked up by helicopter and the other crew got to shore. The next day, 24 April, a force of 75 SAS, SBS and Royal Marines, advancing with naval gunfire support, reached Grytviken and forced the occupying Argentinians to surrender. The following day the garrison at Leith also surrendered.[90]

Main landings

Prior to the landing eight reconnaissance patrols from G Squadron had been landed on East Falkland between 30 April and 2 May.[92] The main landings were at San Carlos on 21 May. To cover the landings, D Squadron mounted a major diversionary raid at Goose Green and Darwin with fire support from HMS Ardent. While D Squadron was returning from their raid they used a shoulder-launched Stinger missile to shoot down a FMA IA 58 Pucará that had overflown their location.[93] While the main landings were taking place, a four-man patrol from G Squadron had been carrying out a reconnaissance near Stanley. They located an Argentinian helicopter dispersal area between Mount Kent and Mount Estancia. Advising to attack at first light, the resulting attack by RAF Harrier GR3's from No. 1 Squadron RAF destroyed one CH-47 Chinook and the two Aérospatiale Puma helicopters.[94]

Pebble Island

Over the night 14/15 May, D Squadron SAS carried out the raid on Pebble Island airstrip on West Falkland. The force of 20 men from Mountain Troop, D Squadron, led by Captain John Hamilton, destroyed six FMA IA 58 Pucarás, four T-34 Mentors and a Short SC.7 Skyvan transport. The attack was supported by fire from HMS Glamorgan. Under cover of mortar and small arms fire the SAS moved onto the airstrip and fixed explosive charges to the aircraft. Casualties were light, with one Argentinian killed and two of the Squadron wounded by shrapnel when a mine exploded.[95]

Sea King Crash

On 19 May, the SAS suffered its worst loss since the Second World War. A Westland Sea King helicopter crashed while cross-decking troops from HMS Hermes to HMS Intrepid, killing 22 men. Approaching HMS Hermes, it appeared to have an engine failure and crashed into the sea. Only nine men managed to scramble out of a side door before the helicopter sank. Rescuers found bird feathers floating on the surface where the helicopter had hit the water. It is thought that the Sea King was the victim of a bird strike. Of the 22 killed, 18 were from the SAS.[96]

Operation Mikado

Operation Mikado was the code name for the planned landing of B Squadron SAS at the Argentinian airbase at Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego. The initial plan was to crash land two C-130 Hercules carrying B Squadron onto the runway at Port Stanley to bring the conflict to a rapid conclusion.[97] B Squadron arrived at Ascension Island on 20 May, the day after the fatal Sea King crash. They were just boarding the C-130s when word came that the operation had been cancelled.[98]

After Mikado had been cancelled B Squadron were called upon to parachute into the South Atlantic to reinforce D Squadron. They were transported south by the two C-130s equipped with long-range fuel tanks. Only one of the aircraft reached the jump point; the other had to turn back with fuel problems. The parachutists were then transported to the Falkland Islands by HMS Andromeda.[99]

West Falkland

Mountain Troop, D Squadron SAS deployed onto West Falkland to observe the two Argentine garrisons. One of the patrols was commanded by Captain GJ (John) Hamilton, of The Green Howards, who had commanded the raid on Pebble Island. On 10 June, Hamilton and patrol were in an observation point near Port Howard when they were attacked by Argentine forces. Two of the patrol managed to get away but Hamilton and his signaller, Sergeant Fosenka, were pinned down. Hamilton was hit in the back by enemy fire and told Fosenka "you carry on, I'll cover your back". Moments later Hamilton was killed. Sergeant Fosenka was later captured when he ran out of ammunition. The senior Argentine officer praised the heroism of Hamilton who was posthumously awarded the Military Cross.[100]

Wireless Ridge

The last major action for the SAS was a raid on East Falkland on the night of 14 June. This involved a diversionary raid by D and G Squadrons against Argentinian positions north of Stanley, while 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment assaulted Wireless Ridge. Their objective was to set up a mortar and machine gun fire base to provide fire support, while the D Squadron Boat Troop and six SBS men crossed Port William in Rigid Raiders to destroy the fuel tanks at Cortley Hill. After firing Milan and GPMG onto the target areas the ground assault team came under anti-aircraft machine gun fire; the water assault group were also hit by a hail of small arms fire, with all their boats hit and three men wounded, forcing them to withdraw. At the same time, the fire base came under an Argentinian artillery and infantry attack. The Argentinian unit had not been seen from the long-range surveillance of the area as they were dug in on the reverse slope. The SAS then had to call upon their own artillery to silence the Argentinian guns to enable G Squadron to withdraw. The raid was to harass the Argentinian ground forces and was a success, but Argentinian artillery continued to land on the SAS assault position and the route the squadron took on its exfiltration for an hour after they had withdrawn and not on the attacking parachute battalion.[101]

Cambodian–Vietnamese War

Between 1985 and 1989, members of the SAS were dispatched to Southeast Asia to train a number of Cambodian insurgent groups to fight against the People's Army of Vietnam who were occupying Cambodia after ousting the Khmer Rouge regime. The SAS did not directly train any members of the Khmer Rouge, but questions were raised amidst the "murky" factional politics as to the relationship between some of the insurgent groups and the Khmer Rouge.[102]

Gulf War

.jpg.webp)

The Gulf War started after the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq on 2 August 1990. The British military response to the invasion was Operation Granby. General Norman Schwarzkopf was adamant that the use of special operations forces in Operation Desert Storm would be limited. This was due to his experiences in the Vietnam War, where he had seen special operations forces missions go badly wrong, requiring conventional forces to rescue them. Lieutenant-General Peter de la Billière, Schwarzkopf's deputy and former member of the SAS, requested the deployment of the Regiment, despite not having a formal role.[103] The SAS deployed about 300 members with A, B and D Squadrons as well as fifteen members from R Squadron the territorial 22 SAS squadron.[104] This was the largest SAS mobilisation since the Second World War.[104] There was conflict in the Regiment over whether to deploy A or G Squadron to the Gulf. In August 1990, A squadron had just returned from a deployment to Colombia, whereas G Squadron were the logical choice to deploy because they were on SP rotation and had just returned from desert training exercises. However, since A Squadron were not involved in the Falklands War, they were deployed.[105][83]

De la Billière and the commander of UKSF for Operation Granby planned to convince Schwarzkopf of the need for special operations forces with the rescue of a large number of Western and Kuwaiti civilian workers being held by Iraqi forces as human shields, but in December 1990, Saddam Hussein released the majority of the hostages, however the situation brought the SAS to Schwarzkopf's attention. Having already allowed US Army Special Forces and Marine Force Recon to conduct long-range reconnaissance missions, he was eventually convinced to allow the SAS to also deploy a handful of reconnaissance teams to monitor the Main Supply Routes (MSRs).[106]

Initial plans were for the SAS to carry out their traditional raiding role behind the Iraqi lines, and operate ahead of the allied invasion, disrupting lines of communications.[105] The SAS operated from Al Jawf, on 17 January, 128 members of A and D squadron moved to the frontline[107] there they inserted three road-watch teams into western Iraq to establish observation of the MSR traffic on 18 January 1991, the first eight SCUD-B ballistic missiles with conventional explosive warheads fell on Tel Aviv and Haifa, Israel, it was this attempt to bring Israel into the war to undermine the coalition by shattering the coalition of Arab nations arrayed against Iraq, that was directly responsible for a dramatic increase in operations for the Regiment. On that day they were tasked with hunting Scuds. An operational area, known as "SCUD Box," covered a huge swathe of western Iraq south of main Highway 10 MSR, was allocated to the SAS and nicknamed "SCUD Alley", Delta Force deployed north of Highway 10 in "SCUD Boulevard," two flights of USAF F-15Es on "SCUD Watch" would be their main air support component. Both SAS and Delta operations were initially hampered by delays in bringing strike aircraft onto the often time sensitive targets-a problem only partially alleviated by the placing of special forces liaisons with the US Air Force in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[108] On 20 January, they were working behind Iraqi lines hunting for Scud missile launchers in the area south of the Amman — Baghdad highway.[109] The patrols working on foot and in landrovers would at times carry out their own attacks, with MILAN missiles on Scud launchers and also set up ambushes for Iraqi convoys,[110]

The half of B squadron in al-Jauf, Saudi Arabia, were given the task of establishing covert observation posts along the MSR in three-eight-man patrols inserted by helicopter.[111] On 22 January three eight-man patrols from B Squadron were inserted behind the lines by a Chinook helicopter. Their mission was to locate Scud launchers and monitor the main supply route. One of the patrols, Bravo Two Zero, had decided to patrol on foot. The patrol was found by an Iraqi unit and, unable to call for help because they had been issued the wrong radio frequencies, had to try to evade capture by themselves. The team under command of Andy McNab suffered three dead and four captured; only one man, Chris Ryan, managed to escape to Syria. Ryan made SAS history with the "longest escape and evasion by an SAS trooper or any other soldier", covering 100 miles (160 km) more than SAS trooper John 'Jack' William Sillito, had in the Sahara Desert in 1942. The other patrols, Bravo One Zero and Bravo Three Zero, had opted to use landrovers and take in more equipment returned intact to Saudi Arabia.[112]

Meanwhile, A and D squadron mobile patrols were tracking down SCUDs and destroying them if possible, or vector-in strike aircraft. Both squadrons were equipped with six to eight Desert Patrol Vehicles (DPVs) in four mobile patrols/fighting columns. The mobile patrols used the "mothership" concept to resupply their mounted patrols, along with the DPVs, a number of cut-down Unimog and ACMAT VLRA trucks were infiltrated into the area of operations and served as mobile resupply points, themselves being stocked with fuel, ammunition and water by RAF Chinook drops, this meant that the SAS mobility patrols could effectively stay in the area of operations indefinitely. During one mission an operator reportedly destroyed a SCUD launcher with a vehicle-mounted Milan anti-tank guided missile. An Iraqi Army command-and-control site known as "Victor Two" was attacked by the SAS: SAS operators crept in to the facility and set a batch of demolition charges which were counting down to detonation when they were compromised, the SAS destroyed Iraqi bunkers with Milans and LAW rockets, operators engaging in hand-to-hand combat with Iraqi soldiers. The operators broke cover and braved enemy fire to reach their vehicles and escape before the demolition exploded. Another mounted patrol from D squadron was bedding down for the night in a desert wadi, later they discovered they were camped next to an Iraqi communications facility, they were quickly compromised by an Iraqi soldier walking to their position. A firefight erupted between the SAS and at least two regular Iraqi Army infantry platoons. The patrol managed to break contact after disabling two Iraqi technicals (pick-up trucks) that attempted to pursue them, during the chaos of the firefight a supply Unimog had been immobilised by enemy fire and left behind with no sign of the seven missing crew members. The seven SAS operators (one of whom was severely wounded) had captured a damaged Iraqi technical and drove toward the Saudi Arabian border, eventually the vehicle ground to a halt and the men were forced to travel on foot, after 5 days they reached the border.[113]

The desert units were resupplied by a temporary formation known as E squadron, this were made up of Bedford 4-ton trucks and heavily armed SAS Land Rovers. They drove from Saudi Arabia on 10 February, rendezvousing with SAS units some 86 miles inside Iraq on 12 February, returning to Saudi Arabia on 17 February.[114]

Days before the cessation of hostilities, an SAS operator was shot in the chest and killed in an ambush. The Regiment had operated in Iraq for some 43 days, despite the poor state of mapping, reconnaissance imagery, intelligence and weather; additional problems such as the lack of essential kit such as night-vision goggles, TACBE radios and GPS units, they appear to have been instrumental in stopping the SCUDs. There were no further launches after only two days of SAS operations in their assigned "box," despite this, significant questions remain over how many SCUDs were actually destroyed either from the air or on the ground, the Iraqis had deployed large numbers of East German-manufactured decoy vehicles and apparently several oil tankers were erroneously targeted from the air. Despite a US Air Force study arguing that no actual SCUDs were destroyed, the SAS maintain that what they destroyed, often at relative close range, were not decoys and oil tankers. Undoubtedly, the Regiment succeeded in forcing SCUDs to move out of the "SCUD Box" and into north-west Iraq and the increased distances, for an inaccurate and unreliable missile system effectively eliminated the SCUD threat. General Schwarzkopf sent a personal message thanking the Regiment and Delta Force saying "You guys kept Israel out of the war."[115] By the end of the war, four SAS men had been killed and five captured.[116]

The SAS perfected desert mobility techniques during Operation Granby; it would influence US Army Special Forces during initial operations in Afghanistan and Iraq a decade later.[117]

Yugoslav Wars

Bosnian War

In 1994–95, Lieutenant-General Michael Rose, who had been the CO of 22 SAS and Director Special Forces (DSF) during the 1980s, commanded the United Nations Protection Force mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Needing a realistic appreciation of the situation in a number of UN-mandated "safe areas" that were surrounded by Bosnian-Serb forces, he requested and received elements from both A and D squadrons. The operators deployed with standard British Army uniforms, UN blue berets and SA80 assault rifles to "hide in plain sight" under the official cover as UK Liaison Officers. They established the "ground truth" in the besieged enclaves. As these men were trained as forward air controllers, they were also equipped with laser target designators to guide NATO aircraft should the decision be made to engage Bosnian-Serb forces.[117]

During the Siege of Goražde, an SAS operator in UN dress, was shot and killed as a patrol attempted to survey Bosnian-Serb positions. On 16 April 1994, as part of Operation Deny Flight, a Royal Navy Sea Harrier FRS.1 of 801 NAS flying from HMS Ark Royal was shot down by a Serbian SA-7 SAM but its pilot was rescued by a four-man SAS team operating within Goražde. The same team called in a number of airstrikes on armoured columns entering the city, until they were forced to escape through the lines of encircling Serbian paramilitaries to avoid capture and possible execution.[118]

A two-man SAS reconnaissance team was covertly inserted into the UN "safe area" of Srebrenica where a Dutch UN battalion was supposedly protecting the population and thousands of Bosniak refugees from threatening Bosnian Serb forces. The SAS team attempted to call in airstrikes as Serbian forces attacked but were frustrated by UN bureaucracy and ineptitude, they were finally ordered to withdraw and the city fell to the Bosnian-Serb army led by General Ratko Mladić in July 1995, resulting in the genocidal execution of some 8,000 cilivans. The SAS patrol commander wrote a series of newspaper articles about the tragedy, but was successfully taken to court by the MoD in 2002 to stop the publication.[119]

In the aftermath of the Dayton Agreement in December 1995, the SAS remained active in the region, alongside JSOC units in the hunt for war criminals on behalf of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. One such operation in July 1997 resulted in the capture of one fugitive and the death of another when he opened fired on a plain clothed SAS team.[119][120] Another wanted war criminal was captured by the Regiment in November 1998 from a remote safehouse in Serbia, he was driven to the Drina river separating Serbia from Bosnia before being transported across in an SAS Zodiac inflatable boat and helicoptered out the country.[119][121] On 2 December 1998, General Radislav Krstić was travelling in a convoy near the village of Vrsari in the Republika Srpska in northern Bosnia when members of 22 SAS, backed-up by a Navy SEAL unit, blocked off the convoy, disabled Krstić's vehicle with spikes and arrested him.[122]

Reservists were deployed into the Balkans in the mid-1990s as a composite unit known as "V" Squadron where they took part in peace support operations, which allowed regular members of the SAS to be used for other tasks.[123]

Kosovo War

The SAS deployed D squadron to Kosovo in 1999 to guide airstrikes by NATO aircraft and reconnoitre potential avenues of approach should a NATO ground force be committed. Members of G squadron were later dispatched into Kosovo from Macedonia to conduct advanced-force operations and assist in securing a number of bridgeheads in preparation for the larger NATO incursion.[119]

Following the Kosovo war, KFOR, the NATO-led international peacekeeping force was responsible for establishing a secure environment in Kosovo.[124]

On 16 February 2001, a large explosive device blew up a coach travelling through Podujevo from Serbia carrying 57 Kosovo Serbs, killing 11 with a further 45 wounded and missing. The coach had been part of a convoy of 5 coaches, escorted by the Swedish military armoured vehicles under British command, the attack took place in a British Brigade Area; within hours; within hours Serbs within Kosovo formed crowds and began attacking Albanians. On 19 March 2001, 3,000 British and Norwegian troops arrested 22 Albanians suspected in the involvement of the bus attack, G squadron 22 SAS spearheaded the operation, the SAS were specifically requested because it was believed the suspects were armed, the SAS carried out the operation early in the morning, when most of the suspects were asleep.[125]

2001 insurgency in the Republic of Macedonia

In the spring of 2001, fighting between the NLA and Macedonia was intensifying; since at least March 2001, SAS teams observed the Kosovo-Macedonian border. Between July and August the violence escalated, the EU set up a peace deal to grant the 600,000 Albanian minority in Macedonia greater political and constitutional rights; a multinational NATO mission would also deploy to collect the weapons from the 2,500 NLA rebels. In mid August Several four-man SAS patrols accompanied 35 members of Pathfinder Platoon, 16 Air Assault Brigade, into rebel held areas in northern Macedonia, on 21 August, the paratroopers guided in two British army Lynx helicopters into the village of Šipkovica, who were carrying 3 British NATO leaders that met with rebel leaders to the negotiation of the disarmament. Following the negotiations, Ali Ahmeti, the leader of the NLA remarked that "perhaps discrimination against Albanians has come to an end;" the next day the NATO multinational force deployed to Macedonia under Operation Essential Harvest, between 27 August and 27 September they collected 3,000 weapons.[125]

Sierra Leone

The SAS and the SBS were deployed Sierra Leone in support of Operation Palliser against the Revolutionary United Front. They had been on stand-by to effect the relief of a British Army Major and his team of UN observers from a besieged camp in the jungle; additionally, they conducted covert reconnaissance, discovering strengths and dispositions of the rebel forces.[126]

Operation Barras

In 2000, a combined force of D squadron 22 SAS, SBS and men from 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment carried out a hostage rescue operation, code named Operation Barras. The objective was to rescue five members of 1st Battalion Royal Irish Regiment and a Sierra Leone liaison officer who were being held by a militia group known as the West Side Boys (there was a total of 11 hostages taken but six were released in preceding negotiations).[82][126] The rescue team transported in three Chinook and one Lynx helicopter mounted a simultaneous two-pronged attack after reaching the militia positions. After a heavy fire fight, the hostages were released and flown back to the capital Freetown.[127] One member of the SAS rescue team was killed during the operation.[128]

War on Terror

Following the September 11 attacks by al-Qaeda in 2001, the U.S. and its allies began the "War on Terror"; an international campaign to defeat Islamist terrorism.

War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)

Operations against the Taliban and al-Qaeda and other terrorists groups in Afghanistan began in October 2001. In mid-October 2001, A and G squadron of 22 SAS (at the time D squadron was SP duty, while B squadron was overseas on a long-term training exercise), reinforced by members of the 21 and 23 SAS, deployed to northwestern Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom – Afghanistan under the command of CENTCOM. They conducted largely uneventful reconnaissance tasks under the codename Operation Determine, none of these tasks resulted in enemy contact; they travelled in Land Rover Desert Patrol Vehicles (known as Pinkies) and modified ATVs. After a fortnight and with missions drying up, both squadrons returned to their barracks in the UK. After political intersession with Prime minister Tony Blair, the SAS were given a direct-action task – the destruction of an al-Qaeda-linked opium plant in southern Afghanistan, their mission was codenamed Operation Trent. Both A and G squadron successfully completed the mission in 4 hours with only 4 soldiers wounded, it marked the regiments first wartime HALO parachute jump and the operation was the largest British SAS operation in history. Following Operation Trent, the SAS were deployed on uneventful reconnaissance tasks in the Dasht-e Margo desert, returning to Hereford in mid-December 2001; however, small numbers of Territorial SAS from both regiments remained in the country to provide close protection for members of MI6. One newspaper fuelled myth was that a British SAS squadron was at the Battle of Tora Bora, in fact, the only UKSF involved in the Battle was the SBS.[129][130] In mid-December, the SAS escorted a reconnaissance and liaison team on a four-day visit to Kabul. The team was led by Brigadier Barney White-Spunner (commander of 16th Air Assault Brigade), who would assess the logistical challenges, and advise the composition of a UN-mandated force to 'assist in the maintenance of security for Kabul and its surrounding area', also in command of the team was Brigadier Peter Wall (from PJHQ) who would negotiate with the Northern Alliance.[131]

On 7 January 2002, an SAS close-protection team escorted Prime minister Tony Blair and his wife whilst they met with Afghan President Karzai at Bagram Airfield.[132] In 2002 the SAS was involved in operations in the Kwaja Amran mountain range in Ghazni Province and the Hada Hills near Spin Boldak, inserting by helicopter at night, storming villages and grabbing suspects for interrogation.[114] During the period of Operation Jacana, a large proportion of the SAS contingent in Afghanistan fell victim to illness that affected hundreds of other British troops at Bagram Airfield, many had to be quarantined.[133] For his conduct whilst leading the SAS in Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002, Lieutenant Colonel Ed Butler was awarded the DSO.[134] Over the next three years, the SAS, operating with an Afghan counternarcotics force (which they trained and mentored) conducted frequent raids into Helmand province, closely coordinated with the ISAF-led PRT (Provisional Reconstruction Effort), which aimed to assist in creating the conditions for the building of a non-narco-based economy, while improving the political link between the province and the new government in Kabul. These efforts were later reinforced in 2004 by the New Zealand SAS, which patrolled northern Helmand in support of the US PRT efforts. During this period, the SAS teams and the US PRT gained a close familiarity with the province and its people, via a combination of 'hearts and minds'-focused patrolling and precise counternarcotics raiding, which focused on the traders/businessmen rather than poor farmers. They supported their missions with a field hospital, complete with specialist staff (as well as the occasional intelligence specialist), who offered medical assistance to Afghans-a programmed known as MEDCAP. This approach was said to have won over many Helmandis.[135]

In May 2003, G squadron deployed to Iraq to replace B and D squadron at the same time they deployed around a dozen of its soldiers to Afghanistan, every 22nd SAS squadron had this deployment establishment until 2005.[136] Also that year, it was revealed that reserve soldiers from 21 and 23 SAS Regiments were deployed, where they helped to establish a communications network across Afghanistan and also acted as liaison teams between the various political groups, NATO and the Afghan government.[137] SAS reservists supported the British PRT in Mazar-e-Sharif that was established in July 2003 and staffed by 100 members of the Royal Anglian Regiment.[138]

After it was decided to deploy British troops to Helmand Province, PJHQ tasked A Squadron 22 SAS to conduct a reconnaissance of the province between April and May 2005. The review was led by Mark Carleton-Smith, who found the province largely at peace due to the brutal rule of Sher Mohammad Akhundzada, and a booming opium-fuelled economy that benefited the pro-government warlords. In June he reported back to the MoD warning them not to remove Akhundzada and against the deployment of a large British force which would likely cause conflict where none existed.[139][140] In spring 2005, as part of a deployment re-balance, the Director of Special Forces decided to only deploy the 22nd SAS regiment to Iraq until at least the end of operations there, whilst British special forces deployments to Afghanistan would be the responsibility of the SBS; before this, a troop from an SAS squadron deployed to Iraq would be detached and deployed to Afghanistan.[141]

In June 2008 a Land Rover transporting Corporal Sarah Bryant and 23 SAS territorial soldiers Corporal Sean Reeve and Lance Corporals Richard Larkin and Paul Stout hit a mine in Helmand province, killing all four.[142] In October Major Sebastian Morley, their commander in Afghanistan D Squadron 23 SAS, resigned over what he described as "gross negligence" on the part of the Ministry of Defence that contributed to the deaths of four British troops under his command. Morley stated that the MoD's failure to properly equip his troops with adequate equipment forced them to use lightly armoured Snatch Land Rovers to travel around Afghanistan.[143] SAS reservists were withdrawn from frontline duty in 2010.[137] In December 2016, ABC news reported that the DEA's FAST (Foreign-Deployed Advisory Support Teams) teams initially operated in Afghanistan alongside the SAS to destroy small opium processing labs in remote areas of southern Afghanistan.[144]

Following the end of Operation Crichton in Iraq in 2009, two SAS squadrons were deployed to Afghanistan, where the Regiment would focus its operations.[145] The main objective of the SAS and other British special forces units with Afghan forces embedded was targeting Taliban leaders and drug barons using "Carrot and stick" tactics.[146] In 2010, the SAS also took part in Operation Moshtarak, four-man SAS teams and U.S. Army Special Forces team ODA 1231 would perform "find, fix, strike" raids. These resulted in the deaths of 50 Taliban leaders in the area according to NATO, but did not seem to have any real adverse effect on the Taliban's operations. According to the London Sunday Times, as of March 2010 the United Kingdom Special Forces had suffered 12 killed and 70 seriously injured in Afghanistan and seven killed and 30 seriously injured in Iraq.[147][Note 2]

In 2011, a senior British officer in Afghanistan confirmed that the SAS were "taking out 130–140 mid-level Taliban commanders every month."[148] On 12 July 2011, soldiers from the SAS captured two British-Afghans in a hotel in Herat; they were trying to join either the Taliban or al-Qaeda and are believed to be the first Britons to be captured alive in Afghanistan since 2001.[149][150] British newspapers that drew on the Afganistan War Logs revealed the existence of a joint SBS/SAS task force based in Kandahar that was dedicated to conducting operations against targets on the JPEL; British Apache helicopters were frequently assigned to support this task force.[151]

On 28 May 2012, two teams: one from the SAS and another from DEVGRU carried out Operation Jubilee: the rescue of a British aid worker and three other hostages after they were captured by bandits and held in two separate caves in the Koh-e-Laram forest, Badakhshan Province. The assault force killed eleven gunmen and rescued all four hostages.[152]

In December 2014, the NATO officially ended combat operations in Afghanistan, however NATO personnel remained in the country to support Afghan forces in the new phase of the War in Afghanistan. The Telegraph reported that around 100 British Special Forces members including members of the SAS would remain in Afghanistan, along with US Special Forces in a counter-terrorist task force continuing to hunt down senior Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders. They are also assigned there to protect British officials and troops remaining in the country.[153] In December 2015, it was reported that 30 members of the SAS alongside 60 US special forces operators joined the Afghan Army in the Battle to retake parts of Sangin from Taliban insurgents.[154]

In July 2022, a BBC investigation said that unarmed men were repeatedly killed by SAS operatives in suspicious circumstances, focusing in particular on a series of night raids conducted by one squadron over the course of its six-month our in Helmand Province in 2010/11 which may have led to the unlawful killings 54 people.[155] The investigators also said that personnel at the highest echelon of the UK’s special forces including its former director Mark Carleton-Smith were aware of the allegations, but did not report them to the military police when they conducted two investigations involving alleged offences committed by the squadron, despite a legal obligation to do so.[155] In response, the Ministry of Defence said that the investigations by the military police “did not have sufficient evidence to prosecute” and objected to the investigation’s subjective reporting which it said arrived at "unjustified conclusions from allegations that have already been fully investigated".[155]

Kashmir conflict

In 2002, a team comprising Special Air Service and Delta Force personnel was sent into Indian-administered Kashmir to hunt for Osama bin Laden after reports that he was being sheltered by the Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen. US officials believed that Al-Qaeda was helping organize a campaign of terror in Kashmir to provoke conflict between India and Pakistan.[156]

Iraq War

The SAS took part in the 2003 invasion of Iraq under the codename: Operation Row, which was part of CJSOTF-West (Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force – West)[157] B and D Squadrons carried out operations in Western Iraq[158] and Southern Iraq; towards the end of the invasion, they escorted MI6 officers into Baghdad from Baghdad International Airport so they could carry out their missions, both Squadrons were replaced by G Squadron in early May. The US military designated the SAS element in Iraq during the invasion as Task Force 14;[159] in the months following the invasion, the SAS moved from Baghdad International Airport to MSS Fernandez in Baghdad, setting up and linking its "property" next to Delta Force, in summer 2003, following a request for a new mission, the SAS began Operation Paradoxical: The broadly drawn operation was for the SAS to hunt down threats to the coalition, SAS were 'joined at the hip' with Delta Force and JSOC, it also gave them greater latitude to work with US "classified" forces – prosecuting the best available intelligence. However, in winter 2003, they were placed under the command of the Chief of Joint Operations in Northwood, due to scepticism of Whitehall members about the UK mission in Iraq – making it more difficult for the SAS to work with JSOC.[160]

By 2004, The various 22nd SAS regiment squadrons would be part of Task Fore Black to fight against the Iraqi Insurgency, General Stanley McChrystal, the commander of NATO forces in Iraq, has commented on A Squadron 22 SAS Regiment when part of Task Force Black/Knight (subcomponents of Task Force 145), carried out 175 combat missions during a six-month tour of duty.[161] In January 2004, Major James Stenner and Sergeant Norman Patterson were killed when their vehicle hit a concrete roadblock whilst driving through the Green Zone at night; the SAS's targets during this period (before it was integrated into JSOC in late 2005 to early 2006) were former Ba'athist party regime elements. By early 2005, the SAS supplemented their land rover and Snatch vehicles with M1114 Humvee's for better protection; in southern Iraq, the SAS maintained a detachment in called Operation Hathor: consisting of a handful of soldiers based with British forces in Basra. Their primary role was to protect SIS (MI6) officers and to conduct surveillance and reconnaissance for the British Battle Group. In June 2005, after Delta Force took a number of casualties during Operation Snake Eyes, McChrystal asked the UK's DSF whether UK Special Forces would be able to assist, but he declined, citing ongoing British concerns about JSOCs detention facilities and other operational issues such as rules of engagement. This caused conflict between the DSF and the then-new commander of 22 SAS, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Williams, who believed the SAS were wasting their time targeting Ba'athist regime elements and advocated for a closer relationship with JSOC, tensions between them escalated throughout the summer of 2005. Williams met with McChrystal, whom he had a good relationship with, to discuss how he could get the SAS to work more closely with Delta Force and JSOC; McChrystal met with the DSF and explained to him what JSOC was trying to do in Iraq, but the DSF questioned the tactics and in summary, strained relations further. The DSF tried to have Williams transferred, he took the case to General Sir Mike Jackson, Chief of the General Staff, citing a long list of grievances, but his request did not command widespread support; at the end of 2005, the DSF was replaced. Many of issues preventing the SAS and TF (Task Force) Black's integration with JSOC had been resolved by the end of 2005 and TF Black began working more closely with JSOC. By late 2005, British commanders decided that the SAS would do six-month tours of duty, instead of the previous 4-month tours, it was officially confirmed in March 2006. Due to the Basra prison incident, in which the name of the UKSF forces in Iraq 'Task force Black' was leaked to the press, the force was renamed 'Task force Knight'; also in 2005, the regiment began using specially trained dogs, specifically during raids on houses in Baghdad.[162][163]

In mid-January 2006, Operation Paradoxical was replaced by Operation Traction: the SAS update/integration into JSOC, they deployed TGHG (Task Group Headquarters Group): this included senior officers and other senior members of 22 SAS – to JSOCs base at Balad. This was the first deployment of TGHG to Iraq since the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the upgrade now meant that the SAS were "joined at the hip" with JSOC and it gave the SAS a pivotal role against Sunni militant groups, particularly AQI[164] In March 2006, members of B squadron SAS were involved in the release of peace activists Norman Kember, James Loney and Harmeet Singh Sooden. The three men had been held hostage in Iraq for 118 days during the Christian Peacemaker hostage crisis.[165] in April 2006 B squadron, launched Operation Larchwood 4 which was an intelligence coup which led to the death of AQI's leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. In November 2006, Sergeant Jon Hollingsworth was killed in Basra whilst assaulting a house containing a senior al-Qaeda member; he was decorated for his service in this unit.[166] On 20 March 2007 G squadron raided a house in Basra and captured Qais Khazali; a senior Shia militant and an Iranian proxy, his brother and Ali Mussa Daqduq, without casualties. The raid turned out to be most significant raid conducted by British forces in Iraq, gaining valuable intelligence on Iranian involvement in the Shia insurgency. During the Spring and summer of 2007, the SAS suffered several men seriously wounded as it extended its operations into Sadr City.[167] From 2007 to early 2008, A squadron achieved "extraordinary" success impact in destroying al-Qaeda's VIBED network in Iraq, ultimately saving lives.[168] In early 2008, B squadron carried out the regiments first HAHO parachute assault in Iraq.[169] In May 2008, the SAS replaced their Humvee's for new Bushmaster armoured vehicles.[170] On 30 May 2009, Operation Crichton; the UKSF deployment to Iraq ended,[171] over the course of the war, 6 SAS soldiers were killed and a further 30 injured.[172]

Somalia and Yemen

In 2009, members of the SAS and the Special Reconnaissance Regiment were deployed to Djibouti as part of Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa to carry out operations against Islamist terrorists in Yemen and Somalia amid concerns that the countries were becoming alternative bases for the extremists. In Yemen; they operate as part of a counter-terrorism training unit and assisting in missions to kill or capture AQAP leaders, in particular; they were hunting down for the terrorists behind the Cargo planes bomb plot. The SAS was carrying out surveillance missions of British citizens believed to be travelling to Yemen and Somalia for terrorist training and they are also working with US counterparts observing and "targeting" local terror suspects.[173][174] Also in Yemen, the SAS was also liaising with local commandos and provided protection to embassy personnel.[175]

Members of the British SAS and US Army Special Forces trained members of the Yemeni Counter Terrorism Unit (CTU). Following the collapse of the Hadi regime in 2015, all coalition special operations personnel were officially withdrawn.[176]

International military intervention against ISIL