| Part of a series on |

| Uyghurs |

|---|

|

Uyghurs outside of Xinjiang |

The history of the Uyghur people extends over more than two millenia and can be divided into four distinct phases: Pre-Imperial (300 BC – AD 630), Imperial (AD 630–840), Idiqut (AD 840–1200), and Mongol (AD 1209–1600), with perhaps a fifth modern phase running from the death of the Silk Road in AD 1600 until the present.

In brief, Uyghur history is the story of a small nomadic tribe from the Altai Mountains competing with rival powers in Central Asia, including other Altaic tribes, Indo-European empires from the south and west, and Sino-Tibetan empires to the east. After the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in AD 840, ancient Uyghurs resettled from Mongolia to the Tarim Basin and northern parts of China. Ultimately, the Uyghurs became civil servants administering the Mongol Empire.

Contested history

The history of the Uyghur people, including their ethnic origin, is an issue of contention between Uyghur nationalists and Chinese authorities.[1] Uyghur historians view Uyghurs as the original inhabitants of Xinjiang, with a long history. Uyghur politician and historian Muhammad Amin Bughra wrote in his book A history of East Turkestan, stressing the Turkic aspects of his people, that the Turks have a 9,000-year history, while historian Turgun Almas incorporated discoveries of Tarim mummies to conclude that Uyghurs have over 6,400 years of history.[2] The World Uyghur Congress has claimed a 4,000-year history.[3] However, the official Chinese view, as documented in the white paper History and Development of Xinjiang, asserts that the Uyghurs in Xinjiang formed after the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in ninth-century Mongolia, from the fusion of many different indigenous peoples of the Tarim Basin and the westward-migrating Old Uyghurs.[4] The modern Uyghur language is not descended from Old Uyghur; rather, it is a descendant of the Karluk languages spoken by the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[5] After the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate, most Uyghurs settled in the Tarim Basin, while smaller numbers settled in other parts of northern China, where they became known as the "Yellow Uyghurs" or Yugurs, and Salar people.[6] During the Islamic Turkification of Xinjiang, the Kara-khanids, under Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, drove the Uyghurs out of Xinjiang. The name "Uyghur" reappeared after the Soviet Union took the 9th-century ethnonym from the Uyghur Khaganate, then reapplied it to all non-nomadic Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang.[7] Many modern Western scholars, however, do not consider modern Uyghurs to be of direct linear descent from the old Uyghur Khaganate of Mongolia; rather they believe them to be descendants of a number of peoples, of which the ancient Uyghurs are but one.[8][9]

Some Uyghur nationalists claim that they are descended from the Tocharians. Well-preserved Tarim mummies of a people with European physical traits indicate the migration of an Indo-European people into the Tarim area at the beginning of the Bronze Age, around 2,000 BCE. These people probably spoke Tocharian and have been suggested by some to be the Yuezhi mentioned in ancient Chinese texts, who later founded the Kushan Empire.[10][11] Qurban Wäli claims ancient words, written in Sogdian or Kharosthi scripts, to be "Uyghur" instead of Sogdian words absorbed into Uyghur, as proposed by more scrupulous linguists.[12][13] Later migrations brought peoples from the west and northwest to the Xinjiang area, probably speakers of various Iranian languages, such as the Saka tribes. Other ancient people in the region mentioned in ancient Chinese texts include the Xiongnu, who fought for supremacy in the region against the Chinese for several hundred years. Some Uyghur nationalists claim descent from the Xiongnu (as well as being related to the White Huns); however, this view is contested by modern Chinese scholars.[2] This Xiongnu claim originates from various Chinese historical texts: for example, according to the Chinese historical book Weishu, the founder of the Uyghurs was descended from a Xiongnu ruler.[14][15]

Pre-Imperial

Many historians trace the ancestry of modern Uyghur people to the Altaic pastoralists called Tiele, who lived in the valleys south of Lake Baikal and around the Yenisei River. The Tiele first appear in history in AD 357, under the Chinese ethnonym Gaoche, referring to the ox-drawn carts with distinctive high wheels used for yurt transportation. Tiele tribal territories had previously been occupied by the Dingling, an ancient Siberian people once subjugated by the Xiongnu, some of whom would be absorbed into the Tiele following the Xiongnu Empire's collapse. The Tiele practiced some agriculture and were highly developed metalsmiths due to the abundance of easily available iron ore in the Yenisei River. According to Duan Linaqin, the Dingling served as vassal metalsmiths to the Xiongnu, then later to the Rouran and Hepthalite states.[16]

The Book of Sui lists about forty Tiele tribes scattered throughout North and Central Asia, one being 韋紇 Weihe (< MC *ɦʷɨi- ɦet), a transcription of underlying *Uyγur:[17][18][19]

The ancestors of the Tiele were the descend[a]nts of the Xiongnu. There were many clans among the Tiele, who were compactly distributed along the valley from the east of the Western Sea.

- In the North of the Tola [Duluo 獨洛] river, there were Boqut (Pugu, 僕骨, MC buk-kuot), Toŋra (Tongluo, 同羅, MC duŋ-lɑ), Uyγur (Weihe, 韋紇, MC ɦʷɨi- ɦet),[lower-alpha 1] Bayirqu (Bayegu, 拔也古, MC bʷɑt-jja-kuo) and Fuluo (覆羅, MC phək-lɑ), whose leaders were all called Irkin (Sijin, 俟斤, MC ɖʐɨ-kɨn) by themselves. And there were other clans such as Mengchen (蒙陳, MC muŋ-ɖin), Turuhe (吐如紇, MC thuo-ɲjɷ-ɦet), Siqit (Sijie, 斯結, MC sie-ket),[lower-alpha 2] Qun (Hun, 渾, MC ɦuon) and Huxue (斛薛, MC ɦuk-siɛt). These clans had a powerful army of almost 20,000 men.

- In the west of Hami (Yiwu) [伊吾], North of Karashahr (Yanqi), and close to Aqtagh (Bai [White] Mountain), there were Qibi (契弊, CE khet-biɛi), Boluozhi (薄落職, CE bɑk-lɑk-tɕɨk), Yidie (乙咥, CE ʔˠit-tet), Supo (蘇婆, CE suo-bʷɑ), Nahe (那曷, CE nɑ-ɦɑt), Wuhuan (烏讙, CE ʔuo-hʷjɐn),[lower-alpha 3] Hegu (紇骨, CE ɦet-kuot),[lower-alpha 4] Yedie (也咥, CE jja-tet), Yunihuan (於尼讙, CE ʔuo-ɳi-hʷjɐn)[lower-alpha 5] and so on. These clans had powerful army of almost 20 thousands men.

- In the Southwest of Altai Mountain (Jin Mountain), there were Xueyantuo (薛延陀, CE siɛt-jiɛn-dɑ), Dieleer (咥勒兒, CE tet-lək-ɲie), Shipan (十槃, CE ʥip-bʷan), Daqi (達契, CE thɑt-khet) and so on, which have army of more than 10,000 men.

- In the north of Samarkand, close to Ade river, there were Hedie (訶咥, CE hɑ-tet), Hejie (曷嶻, CE ɦɑt-dzɑt),[lower-alpha 6] Bohu (撥忽, CE pʷɑt-huot), Bigan (比干, CE pi-kɑn),[lower-alpha 7] Juhai (具海, CE gju-həi), Hebixi (曷比悉, CE ɦɑt-pi-sit), Hecuosu (何嵯蘇, CE ɦɑ-ʣɑ-suo), Bayewei (拔也未, CE bʷɑt-jja-mʷɨi), Keda (渴達, CE khɑt-thɑt)[lower-alpha 8] and so on, which have an army of more than 30,000 men.

- In the east and west of Deyihai (得嶷海), there were Sulujie (蘇路羯, CE suoluo-kjɐt), Sansuoyan (三索咽, CE sɑm-sɑk-ʔet), Miecu (蔑促, CE met-tshjuok), Longhu (隆忽, CE ljuŋ-huot) and so on, more than 8,000 men.

- In the east of Fulin (拂菻), there were Enqu (恩屈, CE ʔən-kjut), Alan (阿蘭,CE ʔɑ-lɑn),[lower-alpha 9] Beirujiuli (北褥九離, CE pək-nuok-kɨu-lei), Fuwenhun (伏嗢昬, CE bɨu-ʔʷˠɛt-huon) and so on, almost 20,000 men.

- In the South of Northern Sea, there were Dubo (都波, CE tuo-pʷɑ) and so forth.

Although there were so many different names of the clans, they were all called Tiele as a whole. There was no ruler among them, and they belonged to the Eastern and Western Türks, separately. They lived in unsettled places, and moved along with the water and grass. They were good at shooting on horseback, and were fierce and cruel, especially greedy. They live on plundering. The clans close to the west do several kinds of cultivating, and breed more cattle and sheep than horses. Since the establishment of the Türk state, the Tiele help the Türks by participating in battles everywhere, and subdue all the groups in the North.

[...]

Their customs were mostly like those of the Türks. The differences were that the husband should stay in his wife's family, and could not go home until the birth of his children. Also, the dead were to be buried.

In the third year of Daye (607), the Tiele sent an envoy and tribute to the court, and never stopped contact from that year.

In AD 546, the Fufulo led the Tiele tribes in a struggle against the Türk tribe in the power vacuum left by the breakup of the Rouran state. As a result of this defeat, the Tiele were forced into servitude again. This incident marked the beginning of the historic Türk-Tiele animosity that plagued both Göktürk Khanates. (Note: at this time, Tiele replaces Gaoche in Chinese history.) At some point during their subjugation, nine Tiele tribes formed a coalition called Tokuz-Oguzes Nine-Tribes, which included the leading tribe, the Uyghurs, and eight allied tribes: Bugu, Hun, Bayegu, Tongluo, Sijie, Qibi, Abusi, and Gulunwugu(si)[lower-alpha 10][26][27]

In AD 600, Sui China allied with Erkin Tegin, leader of the Uyghur tribe, against the Göktürk Empire, their common enemy. In AD 603, the alliance dissolved in the aftermath of Tardu Khan's defeat, but three tribes came under Uyghur control: Bugu, Tongra, and Bayirqu.

In AD 611, the Uyghur, allied with Xueyantuo, defeated a Göktürk invasion; however, in AD 615, they were placed under Göktürk control again by Shipi Qaghan. In AD 627, the Uyghur, now led by Pusa, again in alliance with the Xueyantuo, participated in another Tokuz-Oguz revolt against the Göktürks. After defeating the Göktürk prince Yukuk Shad, Pusa assumed the title 活頡利發 guo-xielifa < *kat-elteber. In AD 630, the Göktürk Khanate was decisively defeated by Emperor Tang Taizong. However, in AD 646, when the Uyghur leader Tumitu Ilteber (吐迷度) was granted the Chinese title of prefect (Chinese: 刺史; pinyin: cìshǐ), a legal precedent for Uyghur rule was established. The Chinese crushed the Xueyantuo in 646 and appointed Uyghur leader as Anbei Protector (安北都護) over the Mongolian steppe.

From AD 648–657, the Uyghurs, under Porun Ilteber (婆闰), worked as mercenaries for the Chinese in their annexation of the Tarim Basin. In AD 683, the Uyghur leader Dujiezhi was defeated by Göktürks and the Uyghur tribe moved to the Selenga River valley. From this base, they struggled against the Second Göktürk Empire.

By AD 688, the Uyghurs were controlled again by the Göktürks. After a series of revolts coordinated with their Chinese allies, the Uyghurs emerged as the leaders of the Tokuz-Oguz and Tiele once again. In AD 744, the Uyghurs, with their Basmyl and Qarluq allies, under the command of Qutlugh Bilge Köl, with Chinese general Wang Zhongsi (王忠嗣), defeated the Göktürks. The following year, they founded the Uyghur Khaganate at Mount Ötüken. Control of Mt. Ötüken had been, since the Göktürks, a symbol of authority over the Mongolian steppe.

Uyghur Khaganate (AD 744–840)

The Uyghur Khaganate lasted from AD 744 to 840. It was administered from the imperial capital Ordu-Baliq, one of the biggest ancient cities in modern-day Mongolia. When founded by Yaoluoge Yibiaobi, the Khaganate neighboured the Shiwei in the east and the Altai mountains in the west, and also included the Gobi desert within its southern border, thus controlling the entire territory of the ancient Xiongnu; at its greatest extent, the Khaganate reached as far west as Ferghana.[28]

Large numbers of Sogdian refugees came to Ordu-Baliq to escape the Islamic conquest of their homeland. They converted the Uyghur nobility from Buddhism to Manichaeism. Thus, the Uyghurs inherited the legacy of Sogdian culture. Sogdians ran the civil administration of the empire. They were helpful in outflanking the Chinese diplomatic policies that had destabilized the Göktürk Khaganate. Peter B. Golden writes that the Uyghurs not only adopted the writing system and religious faiths of the Indo-European Sogdians, such as Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Christianity, but also looked to the Sogdians as "mentors", while gradually replacing them in their roles as Silk Road traders and purveyors of culture.[29] Indeed, Sogdians wearing silk robes are seen in the praṇidhi scenes of the Uyghur Bezeklik murals, particularly Scene 6 from Temple 9 showing Sogdian donors to the Buddha.[30]

In AD 840, following a famine and civil war, the Uyghur Khaganate was overrun by an alliance of Tang-dynasty China and the Kirghiz, another Turkic people. As a result, the majority of tribal groups formerly under Uyghur control migrated to what is now northwestern China, especially to the Turfan basin of the modern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region. The Yenisei Kyrgyz Khaganate of the Are family bolstered his ties and alliance to the Tang dynasty imperial family against the Uyghur Khaganate by claiming descent from the Han-dynasty Han Chinese general Li Ling, who had defected to the Xiongnu and married a Xiongnu princess, daughter of Qiedihou Chanyu, and was sent to govern the Jiankun (Ch'ien-K'un) region, which later became Yenisei. Li Ling was a grandson of Li Guang (Li Kuang) of the Longxi Li family, descended from Laozi, which the Tang dynasty Li Imperial family claimed descent from.[31] The Yenisei Kyrgyz and Tang dynasty launched a victorious successful war between 840 and 848 to destroy the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia and its centre at the Orkhon valley, using their claimed familial ties as justification for an alliance.[32] Tang-dynasty Chinese forces under General Shi Xiong wounded the Uyghur Khagan (Qaghan) Ögä, seized livestock, took 5,000–20,000 Uyghur Khaganate soldiers captive, and killed 10,0000 Uyghur Khaganate sources on 13 February 843 at the battle of Shahu mountain.[33][34][35]

Several laws enforcing racial segregation of foreigners from Chinese were passed by the Han Chinese during the Tang dynasty. In 779, the Tang dynasty issued an edict that forced Uyghurs in the capital to wear their ethnic dress, stopped them from marrying Chinese females, and banned them from pretending to be Chinese. One of the reasons why the Chinese disliked Uyghurs was that they practiced usury.[36]

Uyghur kingdoms

Following the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate, the Uyghur gave up Mongolia and dispersed into present-day Gansu and Xinjiang. In 843, Chinese forces watched over Uyghur remnants located in Shanxi province during a rebellion, until reinforcements arrived.[37] The Uyghur later founded two kingdoms:

Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom, the easternmost state formed by the Yugur people (AD 870–1036), with its capital near present-day Zhangye in the Gansu province of China. There, the Uyghur converted from Manichaeism to Tibetan and Mongol Buddhism. Unlike Turkic peoples further west, they did not later convert to Islam. Their descendants are now known as Yugurs (or Yogir, Yugur, and Sary Uyghurs, literally meaning "yellow Uyghurs") and are distinct from modern Uyghurs. In AD 1028–1036, the Yugurs were defeated in a bloody war and forcibly absorbed into the Tangut kingdom. These Yugurs remained Buddhist and did not convert to Islam.

Kingdom of Qocho, created during AD 856–866, is also called the "Idiqut" ("Holy Wealth, Glory") state and was based around the cities of Qocho (winter capital) near Turpan, Beshbalik (summer capital), Kumul, and Kucha. A Buddhist state, with state-sponsored Buddhism and Manichaeism, it can be considered the center of Uyghur culture. The Uyghurs sponsored the construction of many of the temple caves in nearby Bezeklik. They abandoned the old alphabet and adopted the scripts of the local population, which later came to be known as the Uyghur script.[38] The Idiquts (title of the Karakhoja rulers) ruled independently until they become a vassal state of the Kara-Khitans. In 1209, the Kara-Khoja ruler Idiqut Barchuq declared his allegiance to the Mongols under Genghis Khan and the kingdom existed as a vassal state until 1335. After they submitted to the Mongols, the Uyghurs went into the service of the Mongol rulers as bureaucrats, providing the expertise that the initially illiterate nomads lacked.[39] The Uyghurs of the Kingdom of Qocho were allowed significant autonomy by the Mongols, but their nation was finally destroyed by the Chaghataid Mongols in the late 14th century.

Polities claimed to be Uyghur

Modern Uyghurs claim that the reign of a Kara-Khanid Khanate is a significant part of Uyghur culture and history. Kara-Khanids, or the Karakhans (Black Khans) Dynasty, was a state formed by a confederation of Karluks, Chigils, Yaghmas, and other Turkic tribes.[40] Some historians have argued that the Karakhanids were linked to the Uyghurs of Uyghur Khaganate through the Yaghmas, a people associated with the Toquz Oghuz, although other historians disagree with this theory.[41] The Karakhanid Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan (920–956 AD) converted to Islam in 934, and a mass conversion of the Karakhanids followed in 960. The first capital of the Karakhanids was established in the city of Balasagun in the Chu River Valley and later moved to Kashgar.

During the Kara-Khanid period, mosques, schools, bridges, and caravansarais were constructed in the cities. Kashgar, Bukhara, and Samarkand became centers of learning, and Turkic literature developed. Among the most important works of the period is Kutadgu Bilig ("The Knowledge That Gives Happiness"), written by Yusuf Balasaghuni between the years 1060 and 1070, and Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk ("Compendium of the languages of the Turks") by Mahmud al-Kashgari, who actually distinguished the Islamic Karakhanids, whom he called "Khâqâni Turks" or just "Turks", from the Buddhist Uyghurs in Qocho, whom he sometimes called "Uyghur infidel[s]" and considered enemies.[42][43][44] The tazkirahs of later periods, such as the Tazkirah of the Four Sacrificed Imams, that tells the story of the early Karakhanids, helped forge the identity of the settled Turkic Altishahr people, who would become the modern Uyghurs.[45]

After the rise of the Seljuk Turks in Iran, the Karakhanids became their vassals. The Karakhanid states later submitted and served the suzerainty of the Kara-Khitans, who defeated the Seljuks in the Battle of Qatwan. The Karakhanid states finally ended when they were divided up between the Khwarezmids and Kuchlug, an usurper of the Kara-Khitan's throne.

Most Uyghur inhabitants of the Besh Balik and Turpan regions did not convert to Islam until the 15th-century expansion of the Yarkand Khanate, a Turko-Mongol successor state based in western Tarim. Before converting to Islam, Uyghurs were Tengriist, Manichaeans, Buddhists, or Nestorian Christians.

Mongol period 1210–1760

The Uighur Idiqut, Barchukh, voluntarily submitted to Genghis Khan (r.1206–1227) and was given his daughter, Altani (ᠠᠯᠲᠠᠨ) in 1209.[46] From the 1260s onwards, they were directly controlled by the Yuan dynasty of the Great Khagan Kublai (r.1260–1294). Starting from the 1270s, the Mongol princes Qaidu and Duwa from Central Asia repeatedly launched raids into Uighurstan to take control from the Yuan. Most of the Uighurs, including the ruling dynasty, fled to Gansu, which was then under the Yuan dynasty. The Uighur troops served the Mongol war machine in Central Asia, China, and the Middle East. Because they were one of the many highly developed nations under the Mongols, the Uighurs held high positions at the Mongol court. Tata-tunga was the first scribe of Genghis Khan and mastermind behind the Uighur-Mongolian script that the Mongols used. The founder of the Eretna (1335–1381) in Anatolia was a Uighur commander of the Ilkhanate.

The Chagatai Khanate was a Mongol ruling khanate controlled by Chagatai Khan, second son of Genghis Khan. Chagatai's ulus, or hereditary territory, consisted of the part of the Mongol Empire that extended from the Ili River (today in eastern Kazakhstan) and Kashgaria (in the western Tarim Basin) to Transoxiana (modern Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan). The exact date that the control of Turfan and other areas of Uighurstan was transferred to another Mongol dynasty, Chagatai Khanate, is unclear.[47] Many scholars claim Chagatai Khan (d.1241) inherited Uighurstan from his father, Genghis Khan, as appanage, in the early 13th century.[48] By the 1330s, the Chagatayids exercised full authority over the Uighur Kingdom in Turfan.[49]

After the death of the Chagatayid ruler Qazan Khan in 1346, the Chagatai Khanate was divided into western (Transoxiana) and eastern (Moghulistan/Uyghuristan) halves, which was later known as "Kashgar and Uyghurstan", according to Balkh historian Makhmud ibn Vali (Sea of Mysteries, 1640). By 1348, the Mogul (Mongol in Persian) khan, Tughlug Timur, had converted, along with his 160,000 subjects. A small Mongol dynasty, Qara Del, was founded in Hami, where the Uighurs also lived in 1389.

Mogulistan

Kashgar historian Muhammad Imin Sadr Kashgari recorded Uyghurstan in his book Traces of Invasion (Asar al-futuh) in 1780. Power in the western half devolved into the hands of several tribal leaders, most notably the Qara'unas. Khans appointed by the tribal rulers were mere puppets. In the east, Tughlugh Timur (1347–1363), an obscure Chaghataite adventurer, gained ascendancy over the nomadic Mongols and converted to Islam. In 1360 and again in 1361, he invaded the western half in the hope of reunifying the khanate. At their greatest extent, the Chaghataite domains extended from the Irtysh River in Siberia down to Ghazni in Afghanistan, and from Transoxiana to the Tarim Basin.

Tughlugh Timur was unable to completely subjugate the tribal rulers. After his death in 1363, the Moghuls left Transoxiana, and the Qara'unas' leader Amir Husayn took control of Transoxiana. Tīmur-e Lang (Timur the Lame), or Tamerlane, a Muslim native of Transoxiana who claimed descent from Genghis Khan, desired control of the khanate for himself and opposed Amir Husayn. He took Samarkand in 1366 and was recognized as emir in 1370, although he continued to officially act in the name of the Chagatai khans. For over three decades, Timur used the Chagatai lands as the base for extensive conquests, conquering the rulers of Herat in Afghanistan, Shiraz in Persia, Baghdad in Iraq, Delhi in India, and Damascus in Syria. After defeating the Ottoman Turks at Angora, Timur died in 1405 while marching on Ming-dynasty China. The Timurid dynasty continued under his son, Shah Rukh, who ruled from Herat until his death in 1447.

By 1369, the western half (Transoxiana and further west) of the Chagatai Khanate had been conquered by Tamerlane in his attempt to reconstruct the Mongol Empire. The eastern half, mostly under what is now Xinjiang, remained under Chagatai princes that were at time allied or at war with Timurid princes. Until the 17th century, all the remaining Chagatai domains fell under the theocratic regime of Uyghur Apak Khoja and his descendants, the Khojijans, who ruled Altishahr in the Tarim Basin.

Both the Tarim Basin as well as Transoxiana (in modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) became known as Moghulistan or Mughalistan, after the ruling class of Chagatay and Timurid states descended from the "Moghol" tribe of Doghlat. They were Islamicized and Turkified in language. This Moghol Timurid ruling class established the Timurid rule on the Indian Subcontinent known as the Mughal Empire.

In the eastern portion of the Chagatai Khanate, known as the Eastern Chagatai Khanate to Chinese historians and as Moghulistan to Russian historians, the culture of the Karakhanids dominated the largely Muslim state, and the Buddhist populations of the former Karakhoja Idikut-ate largely converted to the Muslim faith. All Chagatai-speaking Muslims, regardless of whether they lived in Turpan or Kashgar, became known by their occupations as Moghols (ruling class), Sarts (merchants and townspeople), and Taranchis (farmers). This triple division of classes among the same Muslim Turkic folk also existed in Transoxiana, regardless of whether they were under Timurid or Chagatay rule.

The Eastern Chagatai Khanate was marked by instability and internecine warfare, with Kashgar, Yarkant, and Qomul as major centers. Some Chagatay princes allied with the Timurids and Uzbeks of Transoxiana, and some sought help from the Buddhist Kalmyks. The Chagatay prince Mirza Haidar Kurgan escaped his war-torn homeland of Kashgar in the early 16th century to Timurid Tashkent, only to be evicted by the invading Shaybanids. Escaping to the protection of his Mughal Timurid cousins, then rulers of Delhi, he gained his final post as governor of Kashmir and wrote the famous Tarikh-i-Rashidi, widely acclaimed as the most comprehensive work on the Uyghur civilization during the East Turkestani Chagatay reign.[50]

The Khojijans were originally the Aq Tagh tariqa of the Naqshbandi order, which originated in Timurid Transoxiana. Struggles between two prominent Naqshbandi tariqas, the Aq Taghlik and the Kara Taghlik, engulfed the Eastern Chagatai domain in the late 17th century. Apaq Khoja triumphed both as a national religious and political leader. The last ruling Chagatay princess married one of the ruling Khojijan princes (descendants of Apaq) and became known as Khanum Pasha. She ruled brutally after the death of her husband and singlehandedly slaughtered many of her Khojijan and Chagatayid rivals. She was known to have boiled alive the last Chagatayid princess who could have continued the dynasty. The Khojijan dynasty fell into chaos, despite the brutality of Khanum Pasha.

During the Ming Turpan Border Wars, the Chinese Ming dynasty defeated invasions by the Uyghur Kingdom of Turpan.

The Zhengde Emperor of the Ming dynasty had a homosexual relationship with a Uyghur Muslim leader from Hami. His name was Sayyid Husain and he served as Muslim overseer in Hami during the Ming Turpan Border Wars.[51][52] In addition to having relationships with men, the Zhengde Emperor also had relationships with women. He sought the daughters of many of his officials. The other Muslim in his court, a Central Asian called Yu Yung, sent Uighur women dancers to the emperor's quarters for sexual purposes.[53] The emperor favored non-Chinese women, such as Mongols and Uighurs.[54]

The Zhengde Emperor was noted for having a Uighur woman as one of his favorite concubines.[55] Her last name was Ma, and she was reportedly trained in military and musical arts, archery, horse riding, and singing music from Turkestan.[56]

The invasion of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty over the Jungars brought Qing military governorship to the Ili Valley north of Tarim basin. Khojijan princes struggled against Qing rule until the Qing dynasty was overthrown by the Xinhai Revolution.

Occupation and control by the Qing dynasty 1760s–1860s

The Qing dynasty conquered Moghulistan in the 18th century.[57] It invaded Dzungaria in 1759 and dominated it until 1864. The territory was renamed Xinjiang soon after the Qing began their domination of the Dzungar people. "Historians estimate that a million people were slaughtered and the land so devastated that it took a generation for it to recover".[58]

A widespread slave trade in Xinjiang began to take place. The Uyghurs were administered by a system of begs under the control of Manchu military officials.

The Han Hui (currently known as Hui Chinese) and Han Chinese had to wear the queue to demonstrate loyalty to the dynasty, but Turkic Muslims like the Chanto Hui (Uyghur) and Sala Hui (Salars) were not obligated to follow this custom.[59] After the invasion of Kashgar by Jahangir Khoja, Turkistani Muslim begs and officials in Xinjiang eagerly fought for the "privilege" of wearing a queue to show their steadfast loyalty to the Empire. High-ranking begs were granted this right. The eagerness of Turki begs to voluntarily wear the queue contrasted with the Han and Hui, who were forced to wear it.[60]

The Chinese did not distinguish between the Turki Uyghurs and the Central Asian invaders under Jahangir, killing Turks who tried to bribe Chinese citizens and sought refuge with them. Many Chinese and Chinese Muslims (Dungan) had been killed by Jahangir, so they were eager for revenge.[61]

The Uyghur Muslim Sayyid and Naqshbandi Sufi rebel of the Afaqi suborder, Jahangir Khoja, was sliced to death in 1828 by the Manchus for leading a rebellion against the Qing.

Yettishar

During the Dungan revolts of 1864, initiated by Hui Muslims, the Turkic Muslims rose in rebellion in several cities, including Kashgar, Yarkand, Hotan, Aksu, Kucha, and Turpan.[62] The Khoqandi under Yaqub Beg then established the Yettishar state in the region in 1865[63] and gained recognition from the Ottoman Empire in 1873.[64]: 152–153 The rule of Yaqub Beg was disliked by local Kashgaria and his Turkic Muslim subjects due to strict rule, heavy taxes, and declining trade.[65][66][67][64]: 172

Uyghur Muslim forces under Yaqub Beg declared a Jihad against Chinese Muslims under Tuo Ming (T'o Ming) during the Dungan revolt. The Uyghurs thought that the Chinese Muslims were Shafi`i, and since the Uyghurs were Hanafi, they should wage war against them. Yaqub Beg enlisted non-Muslim Han Chinese militia under Xu Xuehong (Hsu Hsuehkung) in order to fight against the Chinese Muslims. T'o Ming's forces were defeated by Yaqub in the Battle of Urumqi in 1870. Yaqub intended to seize all Dungan territory.[68][69] At Kuldja, some Taranchi Turkic Muslims massacred Chinese Muslims, forcing them to flee into Ili.[70]

In the late 1870s, the Qing decided to reconquer Xinjiang, under the leadership of General Zuo Zongtang. As Zuo Zongtang moved into Xinjiang to crush the Muslim rebels under Yaqub Beg, he was joined by Dungan Khufiyya Sufi General Ma Anliang and his forces, which were composed entirely of Muslim Dungan people. Ma Anliang and his Dungan troops fought alongside Zuo Zongtang to attack the Muslim rebel forces.[71]

On 18 December 1877, the army of the Qing entered Kashgar, bringing the state to an end.[72]

Qing reconquest

After this invasion, East Turkestan was renamed "Xinjiang", or "Sinkiang", which itself means "New Dominion" or "New Territory", but should really be known as "Old Territory Newly Returned" (旧疆新归) and was shortened to "Xinjiang" (新疆) in Chinese, by the Qing empire on 18 November 1884.

Meanwhile, the "Great Game" between Russia and Britain was underway in Central Asia, with former ethnic cultures from Afghanistan through Tajikistan and Uzbekistan to Uyghurstan being divided. Artificial lines drawn between Shiite speakers of Eastern Persian and Tajik and Sunni Chagatai speakers within the same Uzbek cultural sphere gave rise to the modern Tajik and Uzbek nationalities, whereas the rather similar Sart-Taranchi populations around Kashgar (Xinjiang) and Andijan (Uzbekistan) divided into Uyghur and Uzbeks, Turpan, Hami, Korla, Kashgar, Yarkant, Yengihissar, Hotan, and Yining, through the Tarim Basin and the edges of Xinjiang, were categorized as Uyghur.

Throughout the Qing dynasty, the sedentary Uyghur inhabitants of the oases around the Tarim, speaking Qarluq/Old Uyghur-Chagatay dialects, were largely known as Taranchi and Sart, ruled by the Moghuls of Khojijan. Other parts of the Islamic World still knew this area as Moghulistan, or as the eastern part of Turkestan.

Republican era 1910–1949

The Uyghur identified themselves to each other by their oasis, as 'Keriyanese', 'Khotanese', or 'Kashgari'. The Soviets met with the Uyghur in 1921 during a meeting of Turkic leaders in Tashkent. This meeting established the Revolutionary Uyghur Union (Inqilawi Uyghur Itipaqi), a communist nationalist organization that opened underground sections in principal cities of Kashgaria and was active until 1926, when the Soviets recognized the post-Qing Sinkiang Government and concluded trade agreements with it.

By 1920, Uyghur nationalism had become a challenge to Chinese warlord Yang Zengxin (杨增新), who controlled Siankiang. Turpan poet Abdulhaliq, having spent his early years in Semipalatinsk (modern Semey) and the Jadid intellectual centres in Uzbekistan, returned to Sinkiang with a pen name that he later styled as a surname: "Uyghur". He wrote the nationalist poem Oyghan, which opened with the line "Ey pekir Uyghur, oyghan!" (Hey poor Uyghur, wake up!) He was later martyred by the Chinese warlord Sheng Shicai in Turpan in March 1933 for inciting Uyghur nationalist sentiments through his works.

There were several Uyghur factions during Yang's rule in Xinjiang, which did not intermarry and were fierce rivals. The Qarataghlik Uyghurs were content to live under Chinese rule, while the Agtachlik Uyghurs were hostile to Chinese rule.[73]

Uyghur independence activists staged several uprisings against post-Qing and Sheng-Kuomintang rule. Twice, in 1933 and 1944, the Uyghurs successfully regained their independence (backed by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin): the First East Turkestan Republic was a short-lived attempt at independence of land around Kashghar, and it was destroyed by the Chinese Muslim army under generals Ma Zhancang and Ma Fuyuan at the Battle of Kashgar (1934). The Uyghurs had revolted with the Kirghiz, who were another Turkic people. The Kirghiz were angry at the Chinese Muslims for crushing their Kirghiz Rebellion, so they and the Uyghurs in Kashgar targeted Chinese Muslims, along with Han Chinese, during their revolt.

The Second East Turkistan Republic existed from 1944 to 1949 in what is now Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture. The Ili Rebellion was fought by the Kuomintang against the Second East Turkestan Republic, the Soviet Union, and the Mongolian People's Republic.

1949–present

In 1949, after the Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang) lost the civil war in China, the Second East Turkestan Republic's rulers refused to form a confederate relation within Mao Zedong's People's Republic of China; however, a plane crash killed many of the East Turkestan Republic's delegation. The surviving leader, Saifuddin Azizi, joined the Chinese Communist Party and professed loyalty to the PRC.[74] Soon afterward, General Wang Zhen marched on East Turkestan through the deserts, suppressing anti-invasion uprisings. Mao turned the Second East Turkistan Republic into the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture and appointed Azizi as the region's first Communist Party governor. Many Republican loyalists fled into exile in Turkey and Western countries.

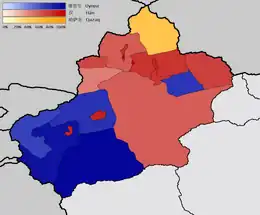

The name Xinjiang was changed to Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Uyghurs are mostly concentrated in southwestern Xinjiang.[75]

In 2004, Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in exile established the East Turkistan Government in Exile, claiming that China occupied East Turkistan.[76]

A committee of independent experts with ties to the United Nations[77] claimed to have credible reports that China holds millions of Uyghurs in secret camps,[78] and many international media reports have said that as many as one million people are being held in Xinjiang internment camps.[79][80][81][82][83][84]

On 24 October 2018, the BBC released details of an extensive investigation into China's "hidden camps" and the extent to which the People's Republic goes to maintain so-called "correct thought".[85]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Chronological names: Yuanhe (袁纥), Wuhu (乌护), Wuhe (乌纥), Weihe (韦纥), Huihe (回纥), Huihu (回鹘).

- ↑ The Old Turkic tribal name is reconstructed as *Sïqïr by Hamilton (1962); Golden (1992) identifies the Sijie 斯結 in the Book of Sui with the Toquz Oghuz tribe Sijie (思結),[20] also mentioned in the Old Book of Tang;[21] Tasağil (1991) tentatively connects Sijie 思結 to the Izgil 𐰔𐰏𐰠 mentioned on the Orkhon Inscriptions;[22] others (e.g. Harmatta (1962), Ligeti (1986), Sinor (1990), Zuev (2004), etc., connect the Izgil to the Western Turkic tribe 阿悉結馬 Axijie ~ 阿悉吉 Axiji and the Volga Bulgar sub-tribe Eskel[23][24]

- ↑ 烏護 Wuhu in Beishi Vol. 99

- ↑ Chronological names: Gekun (鬲昆), Jiankun (坚昆), Jiegu (结骨), Qigu (契骨), Hegu (纥骨), Hugu (护骨), Hejiesi (纥扢斯), Xiajiasi (黠戛斯).

- ↑ 烏尼護 Wunihu in Beishi, Vol. 99

- ↑ Hejie 曷截 in Beishi, Vol. 99

- ↑ Biqian 比千 in Beishi, vol. 99

- ↑ 謁達 Yeda in Beishi Vol. 99

- ↑ Non-Turkic, Iranian-speaking people; according to Lee & Kuang (2017) "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples", Inner Asia 19. p. 201 of 197-239

- ↑ Tang Huiyao manuscript has 骨崙屋骨恐 Gulunwugukong; Ulrich Theobald (2012) amended 恐 (kong) to 思 (si) and proposed that 屋骨思 be transcribed as Oğuz[25]

References

- ↑ Gardner Bovingdon (2010). "Chapter 1 – Using the Past to Serve the Present". The Uyghurs – strangers in their own land. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14758-3.

- 1 2 Tursun, Nabijan (August 2008). "The Formation of Modern Uyghur Historiography and Competing Perspectives toward Uyghur History" (PDF). The China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 6 (3): 87–100. ISSN 1653-4212. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ↑ "Brief History of East Turkestan". World Uyghur Congress. 2004. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ↑ "新疆的历史与发展 [History and Development of Xinjiang]". The State Council of China.

自此,塔里木盆地周围地区受高昌回鹘王国和喀喇汗王朝统治,当地的居民和西迁后的回鹘互相融合,这就为后来维吾尔族的形成奠定了基础。

- ↑ Arik, Kagan (2008). Austin, Peter (ed.). One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520255609.

- ↑ Allworth, Edward A. (1994). Central Asia, 130 Years of Russian Dominance: A Historical Overview. Duke University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-8223-1521-1. "The bulk of the Uyghurs, and undoubtedly with them a small number of Türküt, migrated southwest into the Tarim Basin; fewer groups went southward into the immediate neighborhood of ambivalent China to the provinces of Kan-Su and Ts'ing-Hai (Kökö-nōr), where their descendants still live on as the Sary Yögur (Yellow Uyghurs) and Salar."

- ↑ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2007). Situating the Uyghurs between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7546-7041-4.

- ↑ Susan J. Henders (2006). Susan J. Henders (ed.). Democratization and Identity: Regimes and Ethnicity in East and Southeast Asia. Lexington Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7391-0767-6. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ James A. Millward; Peter C. Perdue (2004). "Chapter 2: Political and Cultural History of the Xinjiang Region through the Late Nineteenth Century". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M. E. Sharpe. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9.

- ↑ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press, New York. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ A. K Narain (March 1990). "Chapter 6 – Indo-Europeans in Inner Asia". In Denis Sinor (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- ↑ Gardner Bovingdon (2004). "Chapter 14 – Contested histories". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang, China's Muslim Borderland. pp. 357–358. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9.

- ↑ Gardner Bovingdon (2015). "Chapter 14 – Contested histories". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang, China's Muslim Borderland. page unnumbered quote: "Like the Chinese historians, the Uyghurs also resort to far-fetched interpretations ... In like fashion, the Uyghur archaeologist, linguist, and philologist Qurban Wäli affects to find “Uyghur” words written in Sogdian or Kharosthi scripts several thousands years ago. That a particular word is Uyghur, rather than a Sogdian word absorbed into Uyghur, as more scrupulous linguist would claim, proves that the Uyghurs and their language were already present in Xinjiang."

- ↑ Peter B. Golden (1992). "Chapter VI – The Uyğur Qağante (742–840)". An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. p. 155. ISBN 978-3-447-03274-2.

- ↑ 舊五代史 Jiu Wudai Shi, Chapter 138. Original text: 回鶻,其先匈奴之種也。後魏時,號爲鐵勒,亦名回紇。唐元和四年,本國可汗遣使上言,改爲回鶻,義取迴旋搏擊,如鶻之迅捷也。 Translation: Hui Hu [Uyghur], originally of Xiongnu stock. During Later Wei, they were called Tiele. They were also called Hui He. In the fourth year of the Yuanhe era, the Khan of their country sent an envoy to submit a request, and the name was changed to Hui Hu. It takes its meaning from turning round to strike rapidly like a falcon.

- ↑ Duan Lianqin, "Dingling, Gaoju and Tiele", p. 325–326.

- ↑ "隋書/卷84 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". zh.wikisource.org.

- ↑ Suribadalaha, "New Studies of the Origins of the Mongols", p. 46–47.

- ↑ Cheng, Fangyi. "The Research on the Identification between the Tiele (鐵勒) and the Oğuric tribes" in Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi ed. Th. T. Allsen, P. B. Golden, R. K. Kovalev, A. P. Martinez. 19 (2012). Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden. p. 104-108

- ↑ Golden, P.B. An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Series: Turcologica (9). p. 156

- ↑ Jiu Tangshu vol. 199b Tiele

- ↑ Tasağil, Ahmet (1991) Göktürkler. p. 57 (in Turkish)

- ↑ Dobrovits, Mihály. "The Altaic World through Byzantine Eyes" in Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 64 (4), p. of pp. 373–409

- ↑ Zuev, Yu.A. (2004) "The Strongest Tribe" in Materials of International Round Table, Almaty, p. 47-48, 53 of pp. 31-67

- ↑ Theobald, U. "Huihe 回紇, Huihu 回鶻, Weiwur 維吾爾, Uyghurs" in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- ↑ Tang Huiyao, vol. 98 txt: "天寶初。迴紇葉護逸標苾。襲滅突厥小殺之孫烏蘇米施可汗。未幾。自立為九姓可汗。由是至今兼九姓之號。[...] 其九姓一曰迴紇。二曰僕固。三曰渾。四曰拔曳固。即拔野古。五曰同羅。六曰思結。七曰契苾。以上七姓部。自國初以來。著在史傳。八曰阿布思。九曰骨崙屋骨恐。此二姓天寶後始與七姓齊列。" engl. tr. "At the beginning of Tien-pao [742], the Hui-ho [Uighur] yabghu I-piao-pi surprised and destroyed the grandson of the little shad of the Turks, Ozmīš qaghan. Before long he set himself up as qaghan of the Chiu-hsing . From this time up to the present day they use the name Chiu-hsing as well [as the name Hui-ho ]. . . . The Chiu-hsing are: (1) Hui-ho [Uighur], (2) P'u-ku, (3) Hun, (4) Pah-yeh-ku, (5) Tung-lo, (6) Ssu-chieh, (7) Ch'i-pi - these seven tribes [ hsing-pu ] appear in historical records from the beginning of the dynasty. - (8) A-pu-ssu, (9) Ku-lun-wu-ku-[k'ong]. I [the editor of the text] suspect that the last two surnames [ hsing ] were first placed on an equality with the seven surnames after Tien-pao" (by Pulleyblank, 1956; quoted & cited in Senga 1990:58)

- ↑ Senga, T. (1990). "The Toquz Oghuz Problem and the Origins of the Khazars". Journal of Asian History. 24 (1): 57–69. JSTOR 419253799.

- ↑ Colin Mackerras, (1972) The Uighur Empire: according to T'ang dynastic histories. Canberra: Australian National University Press. p. 55, 12

- ↑ Peter B. Golden (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 47, ISBN 978-0-19-515947-9.

- ↑ Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134–163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ↑ Drompp, Michael Robert (2005). Tang China and the Collapse of the Uighur Empire: A Documentary History. Vol. 13 of Brill's Inner Asian Library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. pp. 126, 291, 190, 191, 15, 16. ISBN 9004141294.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael R. (1999). "Breaking the Orkhon Tradition: Kirghiz Adherence to the Yenisei Region after A. D. 840". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (3): 390–403. doi:10.2307/605932. JSTOR 605932. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael Robert (2005). Tang China and the Collapse of the Uighur Empire: A Documentary History. Vol. 13 of Brill's Inner Asian Library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 114. ISBN 9004141294.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael R. (2018). "THE UIGHUR-CHINESE CONFLICT OF 840-848". In Cosmo, Nicola Di (ed.). Warfare in Inner Asian History (500-1800). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. BRILL. p. 92. ISBN 978-9004391789.

- ↑ Drompp, Michael R. (2018). "THE UIGHUR-CHINESE CONFLICT OF 840-848". In Cosmo, Nicola Di (ed.). Warfare in Inner Asian History (500-1800). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. BRILL. p. 99. ISBN 978-9004391789.

- ↑ Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang Exotics. University of California Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ↑ Don J. Wyatt (2008). Battlefronts real and imagined: war, border, and identity in the Chinese middle period. Macmillan. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-4039-6084-9. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ Svatopluk Soucek (2000). "Chapter 4 – The Uighur Kingdom of Qocho". A history of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65704-4.

- ↑ Svatopluk Soucek (2000). "Chapter 7 – The Conquering Mongols". A history of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65704-4.

- ↑ Golden, Peter. B. (1990), "The Karakhanids and Early Islam", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24304-1

- ↑ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press, New York. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ Maħmūd al-Kaśġari. (1982) "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. Part I. p. 75-76, 82-88, 139-140; Part II. p. 103, 111, 271-273

- ↑ Golden, Peter, B. "The Turkic World in Mahmud al-Kashgari". J. Bemmann and M. Schmauder (eds.), The Complexity of Interaction along the Eurasian Steppe Zone in the first Millennium CE. Empires, Cities, Nomads and Farmers in Bonn Contributions to Asian Archaeology 7 (Bonn: Vor- und Frühgeschichtliche Archäologie, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, 2015), p. 506,511,519 of pp. 503-555

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

We rode on a boat, and crossed the Ila (a large river); then we headed towards Uighur, and conquered Minglaq

- ↑ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (3): 627–653. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. S2CID 162917965. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Thomas T. Allsen- The Yuan Dynasty and the Uighurs in Turfan in: Ed. Morris Rossabi, China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th centuries, pp. 246

- ↑ Thomas T. Allsen- The Yuan Dynasty and the Uighurs in Turfan in: Ed. Morris Rossabi, China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th centuries, pp. 258

- ↑ Barthold- Four Studies, pp. 43–53

- ↑ Dai Matsui-A Mongolian Decree from the Chaghataid Khanate Discovered at Dunhuang, p.166

- ↑ PHI Persian Literature in Translation.

- ↑ Bret Hinsch (1992). Passions of the cut sleeve: the male homosexual tradition in China. University of California Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-520-07869-7. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑ Société française des seiziémistes (1997). Nouvelle revue du XVIe siècle, Volumes 15–16. Droz. p. 14. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑ Association for Asian Studies. Ming Biographical History Project Committee, Luther Carrington Goodrich, Chao-ying Fang (1976). Dictionary of Ming biography, 1368–1644. Columbia University Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-231-03801-0. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Frederick W. Mote (2003). Imperial China 900–1800. Harvard University Press. p. 657. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑ Peter C. Perdue (2005). China marches west: the Qing conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-674-01684-2. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ Association for Asian Studies. Ming Biographical History Project Committee, Luther Carrington Goodrich, Zhaoying Fang (1976). Dictionary of Ming biography, 1368–1644, Volume 2. Columbia University Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-231-03801-0. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Map of China

- ↑ Tyler, Christian. (2003). Wild West China: The Untold Story of a Frontier Land, John Murray, London. ISBN 0-7195-6341-0. p. 55.

- ↑ Morris Rossabi (2005). Governing China's Multiethnic Frontiers. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98412-0. p. 22.

- ↑ James A. Millward (1998). Beyond the pass: economy, ethnicity, and empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759–1864. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2933-6. p. 204.

- ↑ Christian Tyler (2004). Wild West China: the taming of Xinjiang. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3533-6. p. 68.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ Alexandre Andreyev (2003). Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s. Brill Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 9004129529 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Kim, Hodong (2004). Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804767231.

- ↑ Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh Boulger (1878). The life of Yakoob Beg: Athalik ghazi, and Badaulet; Ameer of Kashgar. London: W. H. Allen. p. 152. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

. As one of them expressed it, in pathetic language, "During the Chinese rule there was everything; there is nothing now." The speaker of that sentence was no merchant, who might have been expected to be depressed by the falling-off in trade, but a warrior and a chieftain's son and heir. If to him the military system of Yakoob Beg seemed unsatisfactory and irksome, what must it have appeared to those more peaceful subjects to whom merchandise and barter were as the breath of their nostrils?

- ↑ Wolfram Eberhard (1966). A history of China. Plain Label Books. p. 449. ISBN 1-60303-420-X. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Linda Benson; Ingvar Svanberg (1998). China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks. M.E. Sharpe. p. 19. ISBN 1-56324-782-8. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ John King Fairbank; Kwang-ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911. Cambridge University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ John King Fairbank; Kwang-ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett (1980). Late Ch'ing. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1871). Accounts and papers of the House of Commons. Ordered to be printed. p. 35. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Lanny B. Fields (1978). Tso Tsung-tʼang and the Muslims: statecraft in northwest China, 1868-1880. Limestone Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-919642-85-3.

- ↑ G. J. Alder (1963). British India's Northern Frontier 1865-95. Longmans Green. p. 67 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Wang, Ke-wen (1998). Modern China: an encyclopedia of history, culture, and nationalism. Taylor & Francis.ISBN 0815307209 p. 103.

- ↑ 2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料,民族出版社,2003/9 (ISBN 7-105-05425-5)

- ↑ Bovingon, Gardner (2010). The Uyghurs: Strangers in their own land. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 150. ISBN 9780231519410. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ↑ "COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ↑ "Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination reviews the report of China". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ↑ "Former inmates of China's Muslim 'reeducation' camps tell of brainwashing, torture". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "Islamic Leaders Have Nothing to Say About China's Internment Camps for Muslims". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ "What The Inside of One of China's Re-Education Camps Looks Like". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Authorities in Xinjiang's Kashgar Detain Uyghurs at 'Open Political Re-Education Camps'". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ "Shocking details emerge from China's re-education camps for Muslims". axios.com. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ "Details Emerge About Xinjiang Reeducation Camp System". China Digital Times. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ China's hidden camps, BBC