Hizb ut-Tahrir حزب التحرير | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Ata Abu Rashta |

| Founder | Taqiuddin al-Nabhani |

| Founded | 1953 |

| Membership | 10,000–1 million |

| Ideology | Pan-Islamism Islamism Muslim supremacism Caliphalism Salafism Jihadism Anti-secularism Anti-Western sentiment Anti-Hindu sentiment Anti-Christian sentiment Anti-nationalism Antisemitism Anti-Zionism Anti-democracy Anti-liberalism Anti-communism |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

| Flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

|

|

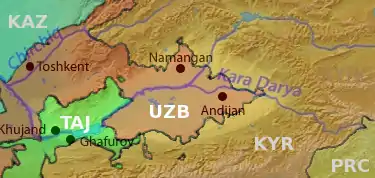

Hizb ut-Tahrir (Arabic: حزب التحرير Ḥizb at-Taḥrīr; Party of Liberation, often abbreviated as HT) is a pan-Islamist and fundamentalist group seeking to re-establish "the Islamic Khilafah (Caliphate)" as an Islamic "superstate" where Muslim-majority countries are unified[1] and ruled under Islamic Shariah law,[2] and which eventually expands globally to include non-Muslim states.[Note 1][Note 2] In Central Asia, the party has expanded since the breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s from a small group to "one of the most powerful organizations" operating in Central Asia.[5] The region itself has been called "the primary battleground" for the party.[6] Uzbekistan is "the hub" of Hizb ut-Tahrir's activities in Central Asia,[7] while its "headquarters" is now reportedly in Kyrgyzstan.[8]

Hizb ut-Tahrir is banned throughout Central Asia,[9] and has been accused by the governments of Central Asia of terrorist activity or illegal importation of arms into their countries. According to globalsecurity.org, the group "is believed by some to clandestinely fund and provide logistical support to a wide range of terrorist operations in Central Asia, and elsewhere, although attacks may be carried out in the names of local groups."[10] Human rights organizations and a former British Ambassador have accused Central Asian governments of torturing Hizb ut-Tahrir members and violating international law in their campaigns against the group.[11]

Among the factors attributed to HT's success in the region are the religious and political "vacuum" of post-Soviet society there; the party's well organized structure; its use of local languages; the relatively comprehensive and easy to understand answers it provides to socio-economic challenges such as poverty, unemployment, corruption, drug addiction, prostitution and lack of education; its call for unifying the Central Asian states which appeals to traders and others frustrated by the severe effect on cross-border trade of the rigid and dysfunctional borders in the region.[12][13]

Hizb ut-Tahrir was first started in Central Asia in Ferghana Valley in Uzbekistan[14] and most HT members in the former Soviet Union are ethnic Uzbeks.[10]

In addition to the five ex-Soviet states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, the adjacent republic of Afghanistan, which was never part of the Soviet Union, and Chinese province of Xinjiang, are (or at least traditionally were in the case of Xinjiang) Muslim majority areas of Central Asia.

History

Islam has been established in Central Asia for centuries, starting with the Battle of Talas in 751. However, during the 1920 and 30s the "cultural assault" of the Soviet Red Army and security forces, weakened religion to the point where "one can talk of a resulting `loss of the collective memory of Sufism in Central Asia`”.[15] The Soviets banned Islamic education, Sufi texts, prayers and hajj pilgrimage, closed religious schools (where religious knowledge was transmitted).[16] In the most populous country of the region, Uzbekistan, there were only 89 mosques in the entire country in Soviet times.[16]

All madrassas and all institutions of secondary or higher Islamic learning closed in the late 1920s. Two Islamic institutes with a very distorted and shortened curriculum began again from 1952 on a tiny scale. Education in Arabic continued only in secret or (after a thorough period of government scrutiny) at the Oriental Institutes of Moscow, Leningrad and a few other places. As a result, the ulema diminished substantially; for example, in Bukhara, the number went down from 45,000 at the time of the Russian revolution to 8,000 in 1955.[16][17]

When the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991, interest among the population in knowing more about Islam was great and religious institutions were freed to expand, but the interpretation of Islam that filled the religious vacuum was not the native Sufism but Islamist interpretations funded by outside petrodollars.[16]

The party was established in the region in the early 1990, but its expansion "took off in earnest" in 1995, when a Jordanian named Salahuddin began disseminating HT literature among the ethnic Uzbek population of the Ferghana Valley, from where it spread.[14] HT has expanded from a small group to one of thousands of members and "by far the largest" radical Islamist movement in the area.[18]

The movement found many recruits following the February 1999 bombings in Tashkent (where it was accused by the Ukbekistan government of participating in the destruction),[14] and after 2001 when it benefited—particularly in Uzbekistan—from the decline of the other important radical Islamic group in Uzbekistan, the salafist jihadist group Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan.[7] As government repression drove HT members out of Ukbekistan they moved to Uzbek areas of other republics and spread the HT message. With time it has spread to among other ethnic groups in the rest of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan.[13][14] By 2004, even ethnic Russians and Koreans were found among arrested HT members.[13] Support for HT is growing among other sectors, teachers, military officers, politicians (especially those whose relatives have been arrested), and other members of the elite.[13]

Structure/operations/size

According to the Jamestown Foundation |Terrorism Monitor, in Central Asia HT targets for recruitment include "socially vulnerable people" such as unemployed, pensioners, students and single mothers; "representatives of local power structures", who can protect party cells from surveillance and prosecution; and "law enforcement personnel" who can "facilitate access to sensitive information".[19]

According to Zeyno Baran, HT is more active in rural areas. This is because the incidence of poverty and unemployment is higher, and family, clan ties, and other informal network ties are stronger than in the more anonymous cities, providing more access to potential recruits, and more safety since anyone rejecting HT's overtures are unlikely to report a family or clan member to the authorities.[20] HT is also active among the commercial class (according to Baran), especially among those who are engaged in wholesale trading operations, and in prisons, which are among "the best" places to convert people to radical Islam. Relatives of the imprisoned, especially women, are particularly easy to recruit. Recruiting influential people within state institutions is critical for overthrowing the government, the third stage of HT's strategy.[21] HT "is known to have successfully penetrated the Kazakhstani media, the Uzbekistani customs bureau, and the Kyrgyzstani parliament".[22] In Kyrgyzstan, the National Security Service Chairman Imankulov publicly accused the Deputy Speaker of Parliament Zhogorku Kenesh and ombudsman Tursunbaj Bakir Uulu of being connected to Islamists, in 2002. According to Baran, Bakir Uulu "is known to protect HT".[23]

In its party work, HT begins by "approaching individuals most likely to embrace radical Islam, communicating and establishing links with them, and disseminating propaganda literature translated into local languages".[24] Leaflets are convenient propaganda tools especially in regions where Internet access is limited or nonexistent, as they can be printed locally and distributed easily.[24] In 2003 alone, Uzbekistani authorities shut down two underground printing houses and confiscated 144,757 leaflets containing appeals to overthrow the country's constitutional order. Also found were over 10,000 copies of HT's constitution, thousands of different issues of Al-Waie and two dozen copies of HT books by al-Nabhani and Zallum.[20] The International Crisis Group reports that in 2004 the organization produced "videocassettes, tape recordings and CDs of leaders’ speeches and sermons.”[25] The recruitment of HT members is based primarily on person-to-person communication. Each member is asked to bring in new recruits personally known to them from places of employment, schools or mosques. “Before an HT member gives a leaflet to a person (someone whom he most likely met at a mosque), the activist generally gets acquainted with the person and sits down to explain that HT is a political, not military, organization.” [26]

Full HT members (known as khizbi) receive a second stage of education and training (in Central Asia this includes comparing the sociopolitical conditions in the republics of Central Asia with other Islamic countries by referring to the publications of the party), and the most promising new members are promoted to the post of Mushrif. Mushrif are trained to organize practical actions and provide training to rank and file members.[19] At the beginning of the third stage of training the "most active, prolific and brilliant" new members — who have "proved their loyalty in real actions" — are promoted to the rank of Naquib. The Naquib manage the general party work at a district level as well as organizing training, propaganda work and the distribution of leaflets.[19] Above the Naquib are the Musaid - the assistant to the head of the regional organization. Above that is the position of Mas’ul - the head of the regional organization who is subordinated to the Muta’amad - leader of Hizb ut-Tahrir in a Central Asian republic. A Muta’amad is responsible for maintaining and strengthening the national branch of the party according to "the unique social, economic and political circumstances" of that Republic. All Muta’amads of the different republics submit to one Amir.[19]

"Rough estimates" of HT's strength in Central Asia range from "20,000 to 100,000 people" according to Karagiannis and McCauley.[7] As of 2003, the International Crisis Group states that estimates of the party's strength throughout Central Asia "vary widely", but a "rough figure is probably 15-20,000".[18] Emmanuel Karagiannis himself "estimates that there are around 30,000 members and many more sympathizers", based on his "extensive fieldwork in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan from September 2003 until February 2005".[7]

HT has been called "without a doubt one of the most powerful organizations" operating in the region (according to Igor Rotar of the Jamestown Foundation).[5] Although another source (the World Almanac of Islamism) describes its support as not "widespread ... anywhere in Central Asia" as of approximately 2013.[27] International Crisis Group also states that the party's "influence should not be exaggerated – it has little public support in a region where there is limited appetite for political Islam", nonetheless it has become "by far the largest" radical Islamist movement in the area.[18]

Policies/issues

While HT is a centralized and hierarchical transnational party, it adjusts its message for its areas of operation. In Central Asia its "primary focus" is devoted to "socioeconomic and human rights issues". It promotes “justice” in contrast to what are widely believed to be "corrupt and repressive state structures".[28] From there it seeks to “guide” Central Asians towards support for the re-establishment of a Caliphate.[28]

The primary aim of HT, according to Zeyno Baran, is to convince Uzbekistanis and other Central Asians "that all of their problems are the fault" of the Uzbekistani and other Central Asian governments and that "the only solution is the destruction of the present political order" and the creation of a "Caliphate based on sharia".[29] In the literature of HT, heads of Central Asian states are "appointed" by Russians and follow their "instructions" to struggle "against Islam, Islamic laws, and Islamic opinions". The governments (HT insists) "bring up children of Muslims at schools, institutes, technical schools and in all other educational institutions in the spirit of atheism, according to programs which had been written by unbelievers." HT vigorously attacks not only Russian influence in the region but also Western attempts to increase trade, development and "economic reform" as exploitation by the kufr:

They carry out economic reforms according to instructions of colonizers. They introduce market economy by creation of joint-stock companies and joint ventures together with colonizers. They plunder and rob riches of Muslims. They bring the investments based on usury into non-industrial fields of national economy, they receive credits under high percent and they exhaust Muslims in debts. . . . They meanly deceive Muslims who are the owners of the fertile grounds and of the huge deposits of minerals. These authorities transform local Muslims into poor men who beg to eat crumbs of waste products from a table of constitutions of unbelievers [and] colonizers.[30][31]

As of 2004, according to Baran, HT was "the most popular radical movement" in Central Asia. Furthermore, (Baran says) those movements while many in number and having different names and tactics, shared goals, regional leaders, and communication networks, and "often" relied on HT's "comprehensive" teachings for an "ideological and theological framework" that justified their actions.[14]

Causes of success

Among the factors attributed to HT's success in the region are the religious and political "vacuum" of post-Soviet society, the handicaps of the competing native Sufi and Saudi-financed Wahhabi interpretations of Islam, the sense of meaning and purpose in being part of a global umma HT offers.[12] For young Muslims, especially those without a job or any prospects for improvement,[29] the party's social network, provided by its study circles, counteracts "loneliness and aimlessness".[29]

The clan-based support system of Central Asia generates suspicion of Western-style democratic modernization with its individualism and meritocracy that HT strenuously opposes.[28] The competing interpretation of Islam provided by native Sufi-based non-Islamist Muslims of the region is disadvantaged both by the enormous destruction to its institutions at the hands of the Red Army and Soviet security forces during the 1920 and 30s,[15] and by its association with the successors of the Soviets—unpopular post-Soviet regimes. In the 1990s the failure of the newly independent states (run by Soviet-era strongmen) "to provide adequate educational, law enforcement and judicial services" to their people, undermined the legitimacy of the native Islamic institutions sponsored by those states.[32] Unlike another religious competitor, the well-financed Wahhabi movement, HT does not require adherence to a "dress code and other legalistic aspects" of the Islamic tradition that are less than popular in post-Soviet Central Asia.[31]

HT's call for unifying Central Asian states appeals to many frustrated with the rigid and dysfunctional borders of the five republics established by Stalin-era "divide and conquer" policies and perpetuated by vested interests of state trading monopolies.[12] The "confusion and conflict" among the governments of the region "has often hindered the joint resolution of common problems".[12] “The idea of a unified state, reminiscent of the Soviet era with no national border between Central Asian states, is supported by traders, customers and many others involved in cross-border trade, which supplies the livelihood of a significant part of Central Asia's population.”[33] (None of the borders are based on those of "any historical state or principality" and divide up regions that "for centuries operated as a political and economic unit, such as the Ferghana Valley".[12])

The secretive, underground operations, "Marxist-Leninist methodology" and "anti-state nature" of HT makes sense in countries whose government is staffed by ex-communists who fear religion.[29]

Compared to other Islamist groups the party is helped by its well organized structure, its use of local languages in its operation (unlike some more purist Salafi movements. This is a major advantage to most locals who do not know Arabic and want to rise within the HT movement), the relatively comprehensive and easy to understand answers it provides to socio-economic challenges such as "extreme poverty, high unemployment, corruption among government officials, drug addiction, prostitution and lack of education".[13] HT also appeals to Central Asians who are not comfortable with the violent attacks of jihadi groups and the strictness and legalism of Wahhabi-oriented Islamist groups.[29]

Locations

Afghanistan

Following the 9/11 attacks and the US attack against the Taliban, HT issued a "communique" stating: "The two enemies of Islam and the Muslims, America and Britain, waged an unjust war against the poor and defenceless Afghan people ..."[34] The "Who Is Who in Afghanistan?" website describes HT as believing that the Taliban's fight against the Afghan government and international supporters is a defense against foreign invasion.[35] In November 2015 the CEO of Afghanistan, Abdullah Abdullah stated that HT was "operating in the academic environment and at community level particularly among the youth" and using democracy and freedom in Afghanistan to serve as "a civil branch of terrorist networks" and convince Afghans to support terrorist activities.[36] The group was "increasing its influence" over the youth in Afghanistan and "actively encouraging young people to join insurgent groups" in Afghanistan's civil war. The Afghan Ministry of Justice acknowledged that the group was active in numerous provinces despite not being licensed to carry out activities.[36]

Azerbaijan

Hizb ut-Tahrir is thought to have several hundred members in Azerbaijan as of 2002. Dozens of its members have been arrested.[37] (Azerbaijan may be considered West Asian rather than Central Asian by many, but like many Central Asian states possesses a Turkic culture.)

Kazakhstan

HT has many fewer members in Kazakhstan than in neighboring countries—no more than 300 as of 2004.[13] Hizb ut-Tahrir was banned by court in Kazakhstan in 2005 and is included in the national list of the terrorist and extremist organizations, which activity is forbidden in the territory of the Republic of Kazakhstan.[38]

Kyrgyzstan

Hizb ut-Tahrir was banned in Kyrgyzstan around late 2004,[39][40] but as that time there were an estimated 3,000–5,000 HT members there.[13]

Until sometime before 2004 the Kyrgyz government was "the most tolerant" of all Central Asian regimes towards HT, according to the Jamestown Foundation. The party headquarters moved from Uzbekistan to Kyrgyzstan.[8] In an interview with a government official in mid 2004, (Zakirov Shamshibek Shakir, the Counselor of the Kyrgyzstan State commission on religious affairs in the Southern region), a representative of the Jamestown Foundation was told that HT members were active distributing leaflets in the Fergana Valley (the most densely-populated area of Central Asia), but were not generally detained by authorities because there was no law against this. However, as the party increased in "confidence and audacity" the government revised its attitude. On October 23, 2004, Kyrgyz President Askar Akayev told the country's Security Council that Hizb ut-Tahrir was one of the "most significant extremist forces" in Kyrgyzstan and its aim was to clearly establish an Islamic state in the Fergana Valley and thus "declare an ideological jihad against the whole of Central Asia".[19][41]

Tajikistan

As of 2004 there were an estimated 3,000–5,000 HT members in Tajikistan.

About 60,000 people lost their lives in Tajikistan's 1992 to 1997 civil war where Islamists and liberal democrats fought against the Soviet old guard and unrest remains as of 2016.[42] Hizb ut-Tahrir activity in Tajikistan is primarily in the north near the Fergana Valley. The Tajik government arrested 99 members of Hizb ut-Tahrir in 2005, sixteen of whom were women, and 58 members in 2006. Out of the 92 extremist suspects detained in 2006, more than half were suspected of membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir.[43][44]

On 19 May 2006 the Khujand city court sentenced ten men, who had called for the government to be overthrown, to jail terms ranging from 9 to 16 years for membership in HuT .[45] Two members of HuT in Khujand were sentenced on 7 June to 10 and 13 years in prison.[46] Makhmadsaid Jurakulov, Chief of Police in Soghd, announced on 31 July 2006 that police had detained Moghadam Madaliyeva, the suspected leader of Hizb ut-Tahrir's female organization in the north.[43] Tajik police arrested 92 terrorists in 2006, 58 of whom were members of HuT.[47] On 17 October 2006Russia's Federal Security Service arrested Rustam Muminov, a member of Hizb ut-Tahrir who fought against the Tajik government in the civil war, and extradicted him to Uzbekistan. The FSB said Muminov "participated in military operations against supporters of the Tajik president and took part in the smuggling of weapons, narcotics, and gold into Tajikistan from Afghanistan"[48]

In 2007 Tajik courts found HT members Makhmudzhon Shokirov guilty of "publicly calling for violent change of the constitutional order in Tajikistan" and "inciting ethnic, racial, and religious enmity"; and Akmal Akbarov guilty for his membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir, and sentenced them to 10 1/2 and 9 3/4 years respectively.[44][47]

Turkmenistan

As of 2004 HT had no "noticeable" presence[13][49][50] in Turkmenistan in part at least because of the nomadic nature of the population, the relatively shallow Islamic roots in its culture, and the extreme repression of the government.[51] (As of 2013 the American Foreign Policy Council also reports that political Islam in general has made little noticeable headway in Turkmenistan.[52])

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan has been called the sight of the "main ideological battle of competition over the region's future".[53] It is the most populous former-Soviet Central Asian country, and possessor of the region's "largest and most effective army".[53] As the "ancient spiritual and cultural center" of the Hanafi school (madhhab) of Sunni Islam, it is more religious than the other ex-Soviet countries and the area where HT first set up operation in Central Asia.[53] As of late 2004, HT had far more members in Uzbekistan than the other ex-Soviet states, with estimates ranging from 7,000 (Western intelligence) up to 60,000 (Uzbekistani government).[13]

HT emerged in Uzbekistan in "the early to mid-1990s".[54] In 1999, six car bombs exploded over one and a half hours in the Uzbekistan capital, Tashkent[55] killing sixteen and injuring over 120. The Uzbek government blamed Islamic militants and responded with massive arrests and torture of pious Muslims. and created a "political vacuum" between a "brutally authoritarian regime" and militant Islamist groups.[56] In July 2009 a number of members and sympathizers of HT were arrested after a pro-government imam and a high-ranking police officer were killed in the capital Tashkent.[57][58]

HT has vigorously attacked the Uzbek political system and president Islam Karimov, as illegitimate and corrupt. One HT pamphlet states, "Only one thing can explain Karimov's shamelessness and hypocrisy, and that is not only that he is a Jew but that he is an insolent and evil Jew, who hates you and your Dīn" [i.e. religion].[59][60]

Starting on March 28, 2004, "four straight days of explosions, bombings and assaults", including the region's "first-ever female suicide bombings", killed 47 people, followed three months later by assaults on the American and Israeli embassies and the prosecutor general's office that killed seven. Uzbek officials reportedly "endeavored assiduously" to tie these events to Hizb-ut-Tahrir—although some were very likely orchestrated by government authorities themselves.[56] Suspects later reportedly testified that they had come to Uzbekistan via Iran and Azerbaijan. The organization "Jamoat" (Society) took "full responsibility" for the attacks, but was later revealed to be Tablighi Jamaat. Uzbekistani Prosecutor-General Rashid Kadyrov stated that the Jamoat militants are influenced by HT's ideology and by the racialism of the Islamic Movement of Turkestan.[61]

Human rights issue

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom estimated that as of 2007 at least 4,500 suspected HT members and associates were serving prison sentences—some for up to 20 years—in Uzbekistan for distributing leaflets and other minor activities.[62]

Among the claims made against strongman President Karimov include those by Craig Murray, former British ambassador to Uzbekistan. Murray states that Hizb ut-Tahrir members have been tortured to stop praying the five daily prayers of Islam (salat), to sign renunciations of their faith, and that two members who refused to do so were

... plunged into a vat of boiling water and ... died ... as a result. I didn't know that at the time, I just saw the photographs of this body in this appalling state; I couldn't work out what could account for it. I sent it to the pathology department of the University of Glasgow; there were a lot of photographs. The chief pathologist of the University of Glasgow, who is now chief pathologist of the United Kingdom, wrote that the only explanation for this was "immersion in boiling water".[63]

HT has condemned the killing of Imam Rafiq Qori Kamoluddin in 2006, allegedly by Kyrgyz and Uzbek security services while he was on his way to fight jihad;[64] and of anti-Uzbekistan government Islamist Imam Shaykh Abdullah Bukhoroy in Zeytinburnu in Istanbul on December 10, 2014,[65][66][67][68][69][70][71] allegedly by the Uzbekistan government.[72][73]

According to Amnesty International, 70 alleged members and sympathizers of HT and other Islamist groups were detained without charge or trial for lengthy periods, tortured and subject to unfair trials in connection with the 2009 killings of a pro-government imam and a high-ranking police officer.[57][58]

At least one analyst, Zeyno Baran, has suggested that HT has developed a "brilliant public relations and propaganda campaign" [74] to frame the fight between HT and Karimov's government as one between a “peaceful” religious group simply engaged in the “battle of ideas”, and a government repressing religion with torture—an example being Western human rights advocates describing the party simply as pious Muslims and "followers of independent imams".[57][58][75]

Baran argues a more accurate portrayal would be of sometimes brutal attempts by an authoritarian regime to combat a radical ideology and anti-constitutional activities, and quotes a question by Uzbek President Karimov:

“If the religious movement [Hizb-ut-Tahrir] intends to set up a caliphate in our Uzbekistan, overthrow the current system, give up the modern style of life and create a state based on sharia law, then how will they be able to do this in a peaceful way?”[76][77]

On the issue of Hizb ut-Tahrir's reply to accusations of terrorism, most Western news groups and governments heard and quoted HT's customary denial in English by its British affiliate, stating that the group would ever engage in violence to re-establishing the Caliphate, and that President Karimov was "once again trying" to use a terrorist incident to crack down on Muslims outside his control. However Baran argues the reply by HT in Tajik language (which many Westerners many have missed) belies HT's claims to non-violence:

If we ever decide to include violence in our program, we shall not blow up things here and there; we shall go directly to his [Karimov's] palace and liquidate him because we are not afraid of anyone but God Almighty. Karimov himself understands that we can do it. He can find from his security services that it is in our power to crush or to liquidate him, should our chosen path allow us to act in this manner. ... However, we are preparing a terrible death for this tyrant under the Caliphate that is approaching nearer every day—with the permission of Allah. Then this tyrant would get his just punishment in this life. The Allah's punishment in the hereafter would be stronger many times more.[77][78]

Xinjiang

As of 2008, the emergence of Hizb ut-Tahrir was a "recent phenomenon" in the autonomous Chinese province of Xinjiang. According to Nicholas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch, the party's influence was "limited" to southern Xinjiang, but "seems to be growing".[79] One obstacle for the party in Xinjiang is that most Uighur activists seek sovereignty for Xinjiang rather than union in a caliphate.[79] As in other parts of Central Asia the party has been designated "terrorist" by the government and is banned.[79] Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan received Uyghur recruits from the diaspora in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.[80] The movement's goal is the takeover of Xinjiang and Central Asia.[81]

See also

Notes

- ↑ From HT pamphlet: “In the forthcoming days the Muslims will conquer Rome and the dominion of the Ummah of Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) will reach the whole world and the rule of the Muslims will reach as far as the day and night. And the Dīn of Muhammad (saw) will prevail over all other ways of life including Western Capitalism and the culture of Western Liberalism”.[3]

- ↑ Founder An-Nabhani describes expansion in terms of following the example of the early Muslim Salaf's invasion and conquest of Persia and Byzantium: "she struck them both [Persia and Byzantium] simultaneously, conquered their lands and spread Islam over almost the whole of the inhabited parts of the world at that time, then what are we to say about the Ummah today; numbering more than one billion, ... She would undoubtedly constitute a front which would be stronger in every respect than the leading superpowers put together.[4]

References

- ↑ Ahmed & Stuart, Hizb Ut-Tahrir, 2009: p.3

- ↑ "Media Office of Hizb-ut-Tahrir. About Hizb ut-Tahrir". Hizb-ut-Tahrir. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ Rich, Dave (July 2015). "Why is the Guardian giving a platform to Hizb ut-Tahrir?". Left Foot Forward. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ an-Nabhani, The Islamic State, 1998: p.238-9

- 1 2 Rotar, Igor (May 5, 2005). "Hizb ut-Tahrir in Central Asia". Terrorism Monitor. 2 (4). Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 43

- 1 2 3 4 KARAGIANNIS, EMMANUEL; MCCAULEY, CLARK (2006). "Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami: Evaluating the Threat Posed by a Radical Islamic Group That Remains Nonviolent". Terrorism and Political Violence. 18 (2): 316. doi:10.1080/09546550600570168. S2CID 144295028. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- 1 2 "World Almanac of Islamism. Uzbekistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ "Uzbek Officials Detain Alleged Hizb Ut-Tahrir Members". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. October 29, 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami (Islamic Party of Liberation)". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Uzbekistan: Muslim Dissidents Jailed and Tortured | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. 2004-03-30. Retrieved 2015-03-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 80

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 78

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004:77

- 1 2 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 70

- 1 2 3 4 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 71

- ↑ Fairbanks, Charles; Godlas, Alan (March 2004). "Understanding Sufism and its Potential Role in U.S. Policy, part 2 "Sufism in Eurasia"". Nixon Center Conference Report. p. 14. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Radical Islam in Central Asia: Responding to Hizb ut-Tahrir". International Crisis Group. 30 June 2003. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Recruiting and Organizational Structure of Hizb ut-Tahrir |Jamestown Foundation |Terrorism Monitor |Volume: 2 Issue: 22 |November 17, 2004 | Evgenii Novikov

- 1 2 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 85

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 86

- ↑ 48 Reuven Paz, “The University of Global Jihad”, in The Challenge of Hizb ut-Tahrir: Deciphering and Combating Radical Islamist Ideology, ed. Zeyno Baran (Washington, DC: The Nixon Center, 2004).

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 87

- 1 2 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 84-5

- ↑ International Crisis Group, “Radical Islam in Central Asia”, p. 22.

- ↑ Anonymous U.S. counter-terrorism analyst, interview by Zeyno Baran, July 13, 2004.

- ↑ "World Almanac of Islamism. Uzbekistan" (PDF). American Foreign Policy Council. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 81

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 79

- ↑ “Whether Kyrgyzstan is Independent”, HT leaflet.

- 1 2 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 82

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 72

- ↑ Anara Tabyshalieva, “Hizb-ut-tahrir's Increasing Activity in Central Asia”, Central Asian Caucus Analysis, January 14, 2004.

- ↑ Hizb ut-Tahrir (9 October 2001). "Communiqué from Hizb ut-Tahrir – America and Britain declare war against Islam and the Muslims". Archived from the original on 1 March 2005. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ↑ "Afghan Biographies. Hizb-ut-Tahrir". Who Is Who in Afghanistan?. 2015-11-23. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- 1 2 Abed Joenda, Mir (23 November 2015). "Abdullah Speaks Out Against Hizb ut-Tahrir". Tolo News. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ Swietochowski, "Azerbaijan: The Hidden Faces of Islam"| World Policy Journal| Fall 2002| p. 75.

- ↑ Committee for Religious Affairs of the Ministry of Culture and Sport of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The list of prohibited on the territory of the RK foreign organizations: «Hizb ut-Tahrir» Archived 2016-01-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Imam Detained In Southern Kyrgyzstan For Hizb Ut-Tahrir Membership". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Kyrgyzstan Silences Popular Imam with Extremism Charges". EurasiaNet.org. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ ITAR-TASS news agency, Moscow, in Russian 1537 gmt 23 Oct 04

- ↑ "Tajikistan poised to slide back towards war". Al Jazeera. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- 1 2 Tajik authorities say female leader of banned Islamist group arrested RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty

- 1 2 Hizb ut-Tahrir activist convicted in Tajikistan Interfax-Religion

- ↑ Tajik court jails Hizb Ut-Tahrir members RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty

- ↑ Tajikistan jails two alleged Hizb ut-Tahrir members RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty

- 1 2 Hizb-ut-Tahrir activist convicted in Tajikistan Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Interfax

- ↑ Russia says expelled Uzbek member Of terrorist group RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty

- ↑ "Turkmenistan" (PDF). World Almanac of Islamism. 2 October 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ Cracks in the Marble: Turkmenistan's Failing Dictatorship, International Crisis Group, January 2003, 25, http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/asia/central-asia/turkmenistan/044%20Cracks%20in%20the%20Marble%20Turkmenistan%20Failing%20Dictatorship.ashx Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 88

- ↑ "Turkmenistan" (PDF). American Foreign Policy Council. c. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004:67-8

- ↑ KARAGIANNIS, EMMANUEL; MCCAULEY, CLARK (2006). "Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami: Evaluating the Threat Posed by a Radical Islamic Group That Remains Nonviolent". Terrorism and Political Violence. 18 (2): 322. doi:10.1080/09546550600570168. S2CID 144295028. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami on Global Security.org| last update 11-07-2011

- 1 2 Ilkhamov, Alisher (April 15, 2004). "Mystery Surrounds Tashkent Explosions". Middle East Research and Information Project. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Annual Report: Uzbekistan 2011". Amnesty International USA. 28 May 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Hizb ut-Tahrir". Uzbekistan Report 2004. Creating Enemies of the State: Religious Persecution in Uzbekistan. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ Hizb ut-Tahrir Uzbekistan, ‘‘Shto poistenne kroestya za attakoi Karimovim na torgovchev?’’ [What is the Real Meaning of Karimov's Attack on Traders?], July 22, 2002, in Russian.

- ↑ KARAGIANNIS, EMMANUEL; MCCAULEY, CLARK (2006). "Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami: Evaluating the Threat Posed by a Radical Islamic Group That Remains Nonviolent". Terrorism and Political Violence. 18 (2): 323. doi:10.1080/09546550600570168. S2CID 144295028. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004:76-7

- ↑ United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, Annual Report 2008 (Washington, DC: May 2008), p.179

- ↑ Murray, Craig (February 24, 2005). ""The pathologist also found that his fingernails had been pulled out. That clearly took me a back." [Transcript of speech]". craigmurray.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ Hizb ut-Tahrir Condemned The Murder of Imam Rafiq Qori Kamoluddin Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine |Turkish Weekly |August 12, 2006

- ↑ "Radical Uzbek Imam Shot Dead In Istanbul". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Russian suspect nabbed in Uzbek preacher's murder". Daily Sabah.

- ↑ "Turkey: Russian citizen detained in connection with Uzbek imam assassination in Istanbul - Ferghana Information agency, Moscow". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Turkey: "Uzbek imam" murder video emerges - Ferghana Information agency, Moscow". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Alleged organizers, killers of Uzbek imam in Turkey arrested, named - Ferghana Information agency, Moscow". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Four more dissident Uzbeks are on assasination [sic] list -report - Asia-Pacific - Worldbulletin News". World Bulletin. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Uzbekistan: Swedish Trial Features Testimony About Alleged International Assassin Network". EurasiaNet.org. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Imam Abdullah Bukhari – May Allah have Mercy on Him – Assassinated in Istanbul!". 22 December 2014.

- ↑ "VIDEO: Sheikh Abdullah Bukhari shot dead in Istandbul". 5Pillars. 27 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 52

- ↑ Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 83

- ↑ (quote from a nationally broadcast address on July 31, 2004) “Karimov Believes Hizb ut-Tahrir Behind Latest Tashkent Bombings”, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, August 2, 2004, http://www.eurasianet.org/redux/departments/insight/%5B%5D articles/eav080204_pr.shtml.

- 1 2 Baran, Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency, 2004: 84

- ↑ “Hizb-ut-Tahrir Explains its Position on Tashkent Bombings”, Newscentralasia.com, August 5, 2004, "NewsCentralAsia". Archived from the original on December 8, 2005. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Blanchard, Ben (6 July 2008). "Radical Islam stirs in China's remote west". Reuters. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ Castets, Rémi (2003). "The Uyghurs in Xinjiang – The Malaise Grows". China Perspectives. French Centre for Research on Contemporary China. 49.

- ↑ ROHDE, DAVID; CHIVERS, C. J. (March 17, 2002). "A NATION CHALLENGED; Qaeda's Grocery Lists And Manuals of Killing". The New York Times.

Books and journals

- Abdul Qadeem Zallum (2000). How the Khilafah was Destroyed (PDF). London: Al-Khilafa Publications. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Ahmed, Houriya; Stuart, Hannah (2009). HIZB UT-TAHRIR IDEOLOGY AND STRATEGY (PDF). Henry Jackson Society. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- Zeyno Baran, ed. (September 2004). The Challenge of Hizb ut-Tahrir: Deciphering and Combating Radical Islamist Ideology. CONFERENCE REPORT (PDF). The Nixon Center.

- Baran, Zeyno (December 2004). "Hizb ut-Tahrir: Islam's Political Insurgency" (PDF). Nixon Center. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- Gross, Ariela (2012). Reaching wa'y. Mobilization and Recruitment in Hizb al-Tahrir al-Islami. A Case Study conducted in Beirut. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz. ISBN 978-3-87997-405-4.

- Hamid, Sadek (2007). "Islamic Political Radicalism in Britain: the case of Hizb-ut-Tahrir". In Tahir Abbas (ed.). Islamic Political Radicalism: A European Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 145–59. ISBN 978-0-74863-086-8.

- Hizb ut-Tahrir (1997). Dangerous Concepts, to Attack Islam and Consolidate the Western Culture (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- Hizb ut-Tahrir (February 2011). The Draft Constitution of the Khilafah State (PDF). Khilafah. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Hizb ut-Tahrir (2005). The Institutions of State in the Khilafah: In Ruling and Administration (PDF). London: Hizb ut-Tahrir. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Hizb ut-Tahrir Britain (29 March 2010). "Hizb ut-Tahrir Media Information Pack". slideshare.net. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Kadri, Sadakat (2012). Heaven on Earth: A Journey Through Shari'a Law from the Deserts of Ancient Arabia ... Macmillan. ISBN 9780099523277.

- Karagiannis, Emmanuel (2010). Political Islam in Central Asia: The Challenge of Hizb Ut-Tahrir. Routledge. ISBN 9781135239428. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- KARAGIANNIS, EMMANUEL; MCCAULEY, CLARK (2006). "Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami: Evaluating the Threat Posed by a Radical Islamic Group That Remains Nonviolent". Terrorism and Political Violence. 18 (2): 315–334. doi:10.1080/09546550600570168. S2CID 144295028. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- Hizb ut-Tahrir (c. 2010). The American Campaign to Suppress Islam (PDF). Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- an-Nabhani, Taqiuddin (1997). The Economic System of Islam (PDF) (4th ed.). London: Al-Khilafah Publications. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- an-Nabhani, Taqiuddin (2002). Concepts of Hizb ut-Tahrir (Mafahim Hizb ut-Tahrir) (PDF). London: Al-Khilafah Publications. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- an-Nabhani, Taqiuddin (1998). The Islamic State (PDF). London: De-Luxe Printers. ISBN 1-89957-400-X.

- an-Nabhani, Taqiuddin (2002). The System of Islam, (Nidham ul Islam) (PDF). Al-Khilafa Publications. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Taji-Farouki, Suha (1996). A Fundamental Quest: Hizb al-Tahrir and the Search for the Islamic Caliphate. London: Grey Seal. ISBN 1-85640-039-5. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Valentine, S. R. (13 May 2010). "Monitoring Islamic Militancy: Hizb-ut-Tahrir: "The Party of Liberation"". Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice. 4 (4): 411–420. doi:10.1093/police/paq015.

- Valentine, Simon Ross (12 February 2010). "Fighting Kufr and the American Raj: Hizb-ut-Tahrir in Pakistan" (PDF). Brief Number 56. Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) at the University of Bradford. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Valentine, S. R. (December 2009). "Hizb-ut-Tahrir in Pakistan". American Chronicle.

- Whine, Michael (4 August 2006). "Is Hizb ut-Tahrir Changing Strategy or Tactics?" (PDF). Thecst.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2015-03-18.

External links

- "Hizb ut-Tahrir", BBC Newsnight, 27 August 2003

- Kyrgyzstan: a clash of civilisations Archived 2008-05-20 at the Wayback Machine Channel 4 News — Video about Hizb ut-Tahrir in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.