Horned helmets were worn by many people around the world. Headpieces mounted with animal horns or replicas were also worn from ancient times, as in the Mesolithic Star Carr. These were probably used for religious ceremonial or ritual purposes, as horns tend to be impractical on a combat helmet. Much of the evidence for these helmets and headpieces comes from depictions rather than the items themselves.

Middle East

Horned hats have been used to signify deities in Mesopotamia, and later, as seen on the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, kings as well. More horns signified higher importance.

Prehistoric Europe

Two bronze statuettes dated to the early 12th century BCE, the so-called "horned god" and "ingot god", wearing horned helmets, found in Enkomi, Cyprus. In Sardinia warriors with horned helmets are depicted in dozens of bronze figures and in the Mont'e Prama giant statues, similar to those of the Shardana warriors (and possibly belonging to the same people) depicted by the Egyptians.

A pair of bronze horned helmets, the Veksø helmets, from the later Bronze Age (dating to c. 1100-900 BCE) were found near Veksø, Denmark, in 1942.[1] Another early find is the Grevensvænge hoard from Zealand, Denmark, (c. 800–500 BCE, now partially lost).

The Waterloo Helmet, a Celtic bronze ceremonial helmet with repoussé decoration in the La Tène style, dating to c. 150–50 BCE, was found in the River Thames, at London. Its abstracted 'horns', different from those of the earlier finds, are straight and conical.[2] Late Gaulish helmets (c. 55 BCE) with small horns and adorned with wheels, reminiscent of the combination of a horned helmet and a wheel on plate C of the Gundestrup cauldron (c. 100 BCE), were found in Orange, France. Other Celtic helmets, especially from Eastern Europe, had bird crests. The enigmatic Torrs Pony-cap and Horns from Scotland appears to be a horned champron to be worn by a horse.

Migration Period

Depicted on the Arch of Constantine, dedicated in 315 CE, are Germanic soldiers, sometimes identified as "Cornuti", shown wearing horned helmets. On the relief representing the Battle of Verona (312) they are in the first lines, and they are depicted fighting with the bowmen in the relief of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge.[3]

A depiction on a Migration Period (5th century) metal die from Öland, Sweden, shows a warrior with a helmet adorned with two snakes, or dragons, arranged in a manner similar to horns. Decorative plates of the Sutton Hoo helmet (c. 600 CE) depict spear-carrying dancing men wearing horned helmets,[4] similar to a figure seen on one of the Torslunda plates from Sweden.[5] Also, a pendant from Ekhammar in Uppland, features the same figure in the same pose and an 8th century find in Staraya Ladoga (a Norse trading outpost at the time) shows an object with similar headgear. An engraved belt-buckle found during excavations by Sonia Chadwick Hawkes in a 7th century grave at Finglesham, Kent in 1964 bears the image of a naked warrior standing between two spears wearing a belt and a horned helmet;[6] a case has been made[7][lower-alpha 1] that the much-repaired chalk figure called the "Long Man of Wilmington", East Sussex, repeats this iconic motif, and originally wore a similar cap, of which only the drooping lines of the neckguard remain. This headgear, of which only depictions have survived, seems to have mostly fallen out of use with the end of the Migration period. Some have suggested that the figure in question does not portray actual headgear, but a mythological object of a god like Odin. A one-eyed figure with similar headgear was found at the site of Uppåkra temple, an alleged center of an Odinic-cult activity. A similar figurine from Levide, Gotland, lacked an eye, apparently removed after its completion. This would link the headgear as a mythological representations rather than depictions of actual helmets.[9] Note that the similar crests to the animal figures on the helmets of the warrior's depicted on the Sutton Hoo helmet has been demonstrated on helmets from Valsgärde, but the depicted crests where grossly exaggerated.

Middle Ages

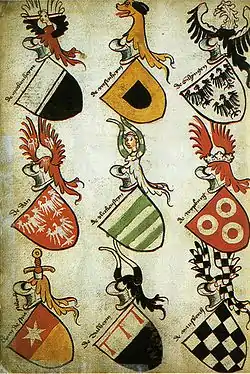

During the High Middle Ages, fantastical headgear became popular among knights, in particular for tournaments.[10] The achievements or representations of some coats of arms, for example that of Lazar Hrebeljanovic, depict them, but they rarely appear as charges depicted within the arms themselves. It is sometimes argued that helmets with large protuberances would not have been worn in battle due to the impediment to their wearer. However, impractical adornments have been worn on battlefields throughout history.

In Asia

_(5911457625).jpg.webp)

In pre-Meiji Restoration Japan, some Samurai armor incorporated a horned, plumed or crested helmet. These horns, used to identify military commanders on the battlefield, could be cast from metal, or made from genuine water buffalo horns.

Indo-Persian warriors often wore horned or spiked helmets in battle to intimidate their enemies. These conical "devil masks" were made from plated mail, and usually had eyes engraved on them.

Popular association with Vikings

Viking warriors are associated with horned helmets in popular culture, but there is no evidence that Viking helmets had horns.[11][12] The depiction of these horned helmets as historical is a fallacy that began in the 1870s. It was part of the construction of great Norse myths to be adopted by Germans, who wanted their own ancestral myths.[13]

The depiction of Vikings in horned helmets was an invention of the 19th-century Romanticist Viking revival.[14] In 1876, Carl Emil Doepler created horned helmets for the first Bayreuth Festival production of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, which has been credited with inspiring this, even though the opera was set in Germany, not Scandinavia.[lower-alpha 2][11] There were also a few earlier, lesser known depictions that inspired Doepler.[13]

A 20th-century example is the Minnesota Vikings American football team, whose logo carries a horn on each side of the helmet. The comic strip character Hägar the Horrible and all male Vikings in the animated TV series Vicky the Viking are always depicted wearing horned helmets, as are numerous characters in the DreamWorks How to Train Your Dragon franchise and in The Lost Vikings video game series. Another popular culture depiction is the riff on Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen by Merrie Melodies in the Chuck Jones-directed cartoon What's Opera, Doc?, which depicts Elmer Fudd wearing a magical horned Viking helmet as he chases Bugs Bunny.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Simpson (1979)[7] notes that Sidgewick (1939)[8] had related the Long Man to the Torslunda plate before Anglo-Saxon and Swedish connections had been fully demonstrated.

- ↑ Unfortunately, few Viking helmets survive intact. The small sample size cannot prove the point definitively, but they are all horn-free. ... Where there were gaps in the historical record, artists often used their imagination to reinvent traditions. Painters began to show Vikings with horned helmets, evidently inspired by Wagner's costume designer, Professor Carl Emil Doepler, who created horned helmets for use in the first Bayreuth production of "Der Ring des Nibelungen" in 1876.[lower-alpha 3]

References

- ↑ "Veksøhjelmene" (PDF). historiefaget.dk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "Horned helmet". Explore / highlights. British Museum. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Speidel, Michael (2004). Ancient Germanic Warriors: Warrior styles from Trajan's column to Icelandic sagas. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 0-415-31199-3.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford, R. (1972). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial: A handbook (2nd ed.). London, UK. fig. 9 p. 30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Davidson, H.R. Ellis (1967). Pagan Scandinavia. London, UK. plate 41.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Hawkes, S.C.; Davidson, H.R.E.; Hawkes, C. (1965). "The Finglesham man". Antiquity. 39 (153): 17–32, esp. pp 27-30. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00031379. S2CID 163986460.

- 1 2 Simpson, Jacqueline (1979). "'Wændel' and the Long Man of Wilmington". Folklore. 90 (1): 25–28. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1979.9716120.

- ↑ Sidgewick, J.B. (1939). "The mystery of the Long Man". Sussex County Magazine. Vol. 13. pp. 408–420.

- ↑ "Odin from Levide - Medieval Histories". medievalhistories.com. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ↑ See the depiction of Wolfram von Eschenbach, and others, in the Codex Manesse.

- 1 2 "Did Vikings wear horned helmets?". The Economist explains. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "Did Vikings really wear horns on their helmets?". The Straight Dope. 7 December 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- 1 2 Frank, Roberta (2000). "The invention of the Viking horned helmet". International Scandinavian and Medieval Studies in Memory of Gerd Wolfgang Weber. pp. 199–208 – via Scribd.

- ↑ Holman, Katherine (2003). Historical Dictionary of the Vikings. Oxford, UK: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4859-7.

External links

- Frank, Roberta (2000). "The invention of the Viking horned helmet". International Scandinavian and Medieval Studies in Memory of Gerd Wolfgang Weber. pp. 199–208 – via Scribd.

- Additional non-Scribd version of Frank article

- "Did Vikings really wear horns on their helmets?". The Straight Dope. 7 December 2004.