Huang Zongying | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

黄宗英 | |||||||||||

Huang Zongying | |||||||||||

| Born | 13 July 1925 Beijing, China | ||||||||||

| Died | 14 December 2020 (aged 95) Huadong Hospital, Shanghai, China | ||||||||||

| Occupation(s) | Actress, writer | ||||||||||

| Notable work | Rhapsody of Happiness Crows and Sparrows Women Side by Side | ||||||||||

| Spouses |

| ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃宗英 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄宗英 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Huang Zongying (Chinese: 黄宗英; 13 July 1925 – 14 December 2020) was a Chinese actress and writer. She starred in many black-and-white films such as Rhapsody of Happiness (1947), Crows and Sparrows (1949), Women Side by Side (1949), and The Life of Wu Xun (1950), all co-starring her third husband Zhao Dan.

She began writing film scripts in the mid-1950s, and later became an acclaimed writer of reportage literature. She was a three-time winner of the National Award for Outstanding Reportage Literature, for "The Flight of the Wild-Geese", "Mandarin Oranges", and "The Wooden Cabin".

Huang married four times. Her marriage with actor Zhao Dan lasted 32 years until his death in 1980. In her later years she married writer Feng Yidai. She had two stepchildren from Zhao's previous marriage, and adopted the two orphaned sons of singer-actress Zhou Xuan.

In 2005, Huang Zongying and Zhao Dan were both named among the "100 best actors of the 100 years of Chinese cinema". Their love story was adapted by Peng Xiaolian into two feature films including Shanghai Rumba (2006).

Early life

Huang was born in 1925 to a prominent scholar-official family in Beijing, originally from Rui'an, Zhejiang Province. Her grandfather and great-grandfather were both holders of the jinshi degree, the highest degree of the imperial examination. Her father Huang Cengming was an engineer who studied in Japan, and her mother Chen Cong was a well-educated housewife. Both her parents held liberal values and allowed their children to pursue their own interests.[1] However, her father died when she was nine and her family fell into poverty.[2]

Strongly influenced by her eldest brother, Huang Zongjiang (黄宗江), who would become an accomplished playwright, Huang Zongying developed a passion in arts and literature. When she was nine years old, she was moved by Bing Xin's essay "To Young Readers". In response, she wrote an essay entitled "Under a Big Tree", which was published in the weekly magazine Huangjin Shidai, edited by her brother.[1]

Career

1940s: acting career

In 1941, Huang followed her brother Zongjiang to Shanghai where she became a stage actress in Huang Zuolin's theatre company. She debuted in Cao Yu's play Metamorphosis[3] and rose to fame in the comedy Sweet Child.[4]

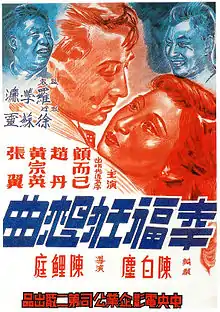

In 1947, she made her screen debut in Shen Fu's film Pursuit before starring in her breakthrough film Rhapsody of Happiness, by the famous director Chen Liting and writer Chen Baichen.[3] In the film she portrayed the heroine, a woman forced into prostitution and drug dealing in war-torn China. Her performance was said to be "of unprecedented artistic quality, capturing with authenticity, naturalness, and control" both the degeneracy and kindness of the character's complex nature.[5] The male lead was her future husband Zhao Dan, China's most celebrated male actor of the time.[3]

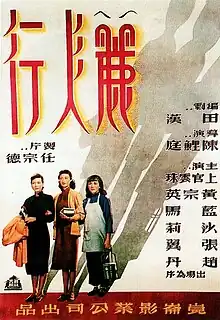

Soon after their marriage in 1948, Huang and Zhao both joined the Kunlun Film Studio, run by the underground Communist Party of China. In less than two years, she acted in several acclaimed films including Women Side by Side and Crows and Sparrows, portraying a diverse range of roles including a revolutionary, a teacher, a prostitute, and a mistress of a government official. Huang and her husband were at the forefront of an era that has been recognized as the Second Golden Age of Chinese cinema.[6]

Early Communist China: acting and writing

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Huang switched to writing as her main career, which was also her childhood passion. She published her first prose collection, Onward Moves the Peace Train, in 1951, followed by two more collections, Stories of Love and A Girl. She did not play a major role after the 1953 film Bless the Children. Under Mao Zedong's directive that "the arts must serve the workers, peasants and soldiers", Chinese films became dominated by stereotypical proletarian "heroes" with few roles suitable for her.[6] Beginning in 1954 she wrote the film scripts for An Everyday Occupation (1955) and The First Spring of the 60s.[7]

Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Mao's wife Jiang Qing, who had been an actress in the 1930s, launched a campaign to persecute former Shanghai colleagues who were familiar with her past. Many of Huang and Zhao's friends in the film and drama industry were driven to death, including Zheng Junli, Cai Chusheng, and Wang Ying.[7] Zhao Dan, among the first to be targeted, was imprisoned for five years, during which Huang had no idea whether he was still alive. She remained free, but was frequently targeted by the Red Guards for physical abuse. Her family, with more than ten people, lived in one small room and had to survive on only 30 yuan a month. Her own children denounced her and Zhao Dan as "counterrevolutionaries".[7]

Post-Cultural Revolution: reportage writing

After the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, Zhao Dan was politically rehabilitated and returned home.[8] Huang resumed her writing and was elected to the executive committee of the China Writers Association. She focused on the reportage genre, which she had begun writing in 1963 before being interrupted by the Cultural Revolution. Instead of the famous and the successful, she chose her subjects mainly among the common people, especially intellectuals who quietly struggled for their ideals but were belittled and denounced by society.[8] In 1977, she published her work Heart in the journal People's Literature commemorating her colleague and friend Shangguan Yunzhu, who had been persecuted to death during the Cultural Revolution. Shangguan's son Wei Ran credited the work with expediting her posthumous political rehabilitation.[9]

Huang often applied scriptwriting techniques, such as switches and flashbacks, to her reportage, and enriched her writing with poetic lyricism.[10] She won the National Award for Outstanding Reportage Literature three times, for her works "The Flight of the Wild-Geese", "Mandarin Oranges", and "The Wooden Cabin".[8] Her story "The Flight of the Wild-Geese" (大雁情) has been translated into English by Yu Fanqin and Wang Mingjie.[11]

In a 2002 article, Huang revealed a conversation she had overheard between Mao Zedong and his biographer Luo Jinan, in which Mao told Luo that if Lu Xun, the leading Chinese writer of the 1930s, had still been alive in the 1950s, he would have had to toe the official line or be held in prison.[12]

Filmography

Film

| Year | English title | Original title | Role | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Rhapsody of Happiness | 幸福狂想曲 | Zhang Yuehua | [13] | |

| Pursuit | 追 | Ye Wenxiu | [14] | ||

| 1948 | Street and Lanes | 街頭巷尾 | Zhao Shuqiu | [14] | |

| The Dawning | 雞鳴早看天 | Wang Guifang | [14] | ||

| 1949 | Welcoming Spring | 喜迎春 | Tao Chenghua | [15] | |

| Women Side by Side | 麗人行 | Li Xinqun | [16] | ||

| The Adventures of Sanmao the Waif | 三毛流浪記 | Guest | [17] | ||

| Crows and Sparrows | 烏鴉與麻雀 | Yu Xiaoying | [18] | ||

| 1950 | The Life of Wu Xun | 武訓傳 | Teacher | [19] | |

| 1953 | Bless the Children | 為孩子们祝福 | Wang Min | [6] | |

| 1956 | Family | 家 | Qian Meifen | [20] | |

| 1958 | Friendly Competition | 你追我趕 | Scriptwriter | [21] | |

| Ordinary Careers | 平凡的事业 | Scriptwriter | [21] | ||

| 1959 | Nie Er | 聶耳 | Feng Feng | [13] | |

| 1960 | The First Spring of the 1960s | 六十年代第一春 | Co-scriptwriter | [7] | |

| 1982 | The Go Masters | 未完の対局 | Kuang Wanyi | [15] | |

| 1988 | Palanquin of Tears | Le palanquin des larmes | Judy Wang | [15] | |

| 2017 | Please Remember Me | 请你记住我 | Herself | [15] |

TV series

| Year | English title | Original title | Role | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Dashilanr | 大柵欄 | Princess | [15] |

Personal life

Marriages

Huang Zongying was married four times. She married her first husband, the conductor Yi Fang (异方), when she was 18, without knowing he suffered from congenital heart disease. He died of a heart attack only 18 days after the wedding.[9][22]

In 1946, she married the playwright Cheng Shuyao, who was from a rich but old-fashioned family which Huang found repressive.[9][22] Forbidden by her husband and mother-in-law to act, she fled the family in Beijing to pursue her acting career in Shanghai.[3] During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Zhao Dan was arrested by the Chinese warlord Sheng Shicai in Xinjiang in 1939, and imprisoned until the end of the war in 1945. Believing the widespread rumour that he had been killed by Sheng, his wife remarried. Huang and Zhao fell in love when filming Rhapsody of Happiness and wedded on New Year's Day of 1948. Numerous filmmakers and actors attended their wedding, which was presided over by the prominent director Zheng Junli.[6] Cheng later married the actress Shangguan Yunzhu, and the two couples remained close friends.[9][22]

Huang considered her 32-year marriage to Zhao Dan the most important of her life, and raised Zhao's two children from his previous marriage. According to her stepdaughter Zhao Qing, she treated her stepchildren like her own. Zhao Dan died from cancer in 1980.[9][22]

In 1993, when she was 68, Huang married for the fourth time, to the writer Feng Yidai (1913–2005).[9][22]

Adoption of Zhou Xuan's sons and lawsuit

In September 1957, the famous actress and singer Zhou Xuan died at the age of 39, leaving behind two young sons, Zhou Min and Zhou Wei. Huang Zongying adopted the two boys and raised them to adulthood. In November 1986, however, Zhou Wei sued Huang for his mother's inheritance worth about 120,000 yuan, which was a huge sum in 1980s China.[23] Zhou Min, on the other hand, sided with Huang and condemned his brother, even questioning whether he was truly Zhou Xuan's son, as she had suffered mental illness before her death and the circumstances surrounding Zhou Wei's birth and the identity of his father were murky. According to Huang's court statements, she had kept Zhou Xuan's property in safe custody and did not distribute it to the brothers because of the dispute between them.[23]

In December 1988, the Shanghai Intermediate People's Court ruled that Zhou Wei was Zhou Xuan's biological son and entitled to half of her inheritance. It also ruled that Huang had violated Zhou Wei's rights when she failed to distribute to him Zhou Xuan's property or disclose details about the property when he reached adulthood. The court ordered Huang to pay Zhou Wei 80,000 yuan.[23]

Death

Huang died of illness at Huadong Hospital on the morning of 14 December 2020.[24][25]

Legacy

In 2005, the centenary of Chinese cinema, the China Film Association organized a vote for China's best actors in history. Huang Zongying and her husband Zhao Dan were both named among the "100 best actors of the 100 years of Chinese cinema".[26]

In 2006, Peng Xiaolian directed the film Shanghai Rumba which is loosely based on the love story of Huang Zongying and Zhao Dan, starring Yuan Quan and Xia Yu.[27] In 2017, Peng directed another feature titled Please Remember Me which also highlights their relationship. Huang Zongying appears as herself in this film.[28]

Actress Yu Hui portrayed Huang Zongying in the 2010 TV series Zhao Dan.[29]

Citations

- 1 2 Lee (1998), p. 248.

- ↑ Zhang (1983), p. 51.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee (1998), p. 249.

- ↑ Song (2013), p. 145.

- ↑ Lee (1998), pp. 249–250.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee (1998), p. 250.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee (1998), p. 251.

- 1 2 3 Lee (1998), p. 252.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mo, Qi (2 January 2017). "92岁黄宗英出文集:从影星到作家,以及她的传奇一生". Thepaper.cn. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ↑ Lee (1998), p. 253.

- ↑ Zhang (1983), p. 47.

- ↑ Song (2013), p. 146.

- 1 2 "永远的银幕甜姐!永远的作家才女!黄宗英,一路走好! - 侬好上海 - 新民网". Xinmin. 14 December 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 China's Screen. China Film Export and Import Corporation. 1983. p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "著名表演艺术家黄宗英逝世 享年95岁_电影". Sohu. 14 December 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ Kuoshu, Harry H. (2002). Celluloid China: Cinematic Encounters with Culture and Society. Carbondale, Illinois: SIU Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8093-2456-9.

- ↑ "Seventy years on, book still sells like hotcakes[2]- Chinadaily.com.cn". China Daily. 7 October 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ Haenni, Sabine; Barrow, Sarah; White, John (2015). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Films. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. p. 606. ISBN 978-1-317-68261-5.

- ↑ Wang, Z. (2014). Revolutionary Cycles in Chinese Cinema, 1951–1979. New York: Springer. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-137-37874-3.

- ↑ Ombres électriques: panorama du cinéma chinois, 1925-1982, à travers une sélection de 60 films : Paris, juin 1982 (in French). Centre de documentation sur le cinéma chinois. 1982. p. 38.

- 1 2 ""角色的种子":甜姐儿黄宗英"变身"文坛作家". East Day. 1 November 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "《可凡》黄宗英:我活着就不能让赵丹"死"了". Netease (in Chinese (China)). 8 May 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 "周璇遗产案黄宗英败诉 周伟获赔偿". Sina (in Chinese). 19 September 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ↑ "China's 'darling girl' dies at the age of 95". Shine. 14 December 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ "著名表演艺术家、作家黄宗英逝世 享年96岁". www.chinanews.com. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ↑ "中国电影百年百位优秀演员" [100 Best Actors of the 100 Years of Chinese Cinema]. Sina (in Chinese). 13 November 2005.

- ↑ "Faster Cha Cha for Shanghai Rumba". Shanghai Daily. 5 January 2006. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ↑ "Pingyao Year Zero: A Report from China's First Authority-Approved, Privately Operated Film Festival". Filmmaker. 2 January 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ↑ "电视剧《赵丹》央八热播 于慧演黄宗英不用酝酿_影音娱乐_新浪网". Sina. 21 December 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

General bibliography

- Lee, Lily Xiao Hong (1998). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: The Twentieth Century, 1912-2000. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0798-0.

- Song, Yuwu (5 July 2013). Biographical Dictionary of the People's Republic of China. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0298-1.

- Zhang, Jie (1983). Seven Contemporary Chinese Women Writers. Translated by Gladys Yang. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-2959-6017-3.