The Hun speech was delivered by German emperor Wilhelm II on 27 July 1900 in Bremerhaven, on the occasion of the farewell of parts of the German East Asian Expeditionary Corps (Ostasiatisches Expeditionskorps). The expeditionary corps were sent to Imperial China to quell the Boxer Rebellion.

The speech gained worldwide attention due to its incendiary content. For a long time, it was considered to be the source of the epithet "Huns" for Germans, which was used by the British to much effect in World War I.

Historical background

The "Hun speech" took place against the historical backdrop of the Boxer Rebellion, an anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising in Qing China between 1899 and 1901. A flashpoint of the rebellion was reached when telegraphic communications between the international legations in Beijing and the outside world were disrupted in May 1900.[1] After the disruption, open hostilities began between foreign troops and the Boxers, who later were supported by regular Chinese forces.[1]

On 20 June 1900, the German envoy to China, Clemens von Ketteler, was shot dead by a regular Chinese soldier[2] while on his way to the Zongli Yamen, a Chinese government body in charge of foreign policy.[1] After this shooting the Qing court declared war against all foreign powers in China and the Siege of the International Legations in Beijing began.[1] Upon the beginning of the siege, the Eight-Nation Alliance – Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States and five European states – dispatched an expeditionary force to intervene and free the legations. After seven weeks, the international expeditionary force prevailed, the Chinese Empress Dowager Cixi fled Beijing, and the foreign alliance looted the city.[1]

The "Hun speech" was delivered by Wilhelm II during a farewell ceremony for some of the troops belonging to the German East Asian Expeditionary Corps (Ostasiatisches Expeditionskorps). It was one of at least eight speeches the Emperor gave on the occasion of the embarkation of the troops.[3] However, most of the German forces dispatched arrived too late to partake in any of the major actions in the conflict. Its first elements arrived at Taku on 21 September 1900, after the international legations had already been relieved.[4]

The speech

The speech was delivered on 27 July 1900. On this Friday, Wilhelm II first inspected two of the three troopships in Bremerhaven, which later that day would set sail for Beijing. The German troopships were the Batavia, the Dresden and the Halle.[5] After inspecting two ships, Wilhelm II returned to his imperial yacht SMY Hohenzollern II and invited the chairman of the Norddeutscher Lloyd, Geo Heinrich Plate, the General Directors Heinrich Wiegand (Norddeutscher Lloyd) and Albert Ballin (HAPAG), dignitaries from the cities of Bremen and Bremerhaven as well as numerous officers to breakfast on board his yacht at 12:00.[6]

At 12:45 the Expeditionary Corps assembled for inspection by the Emperor at the Lloyd Hall, which he carried out at 13:00.[6] During his inspection Wilhelm II was accompanied by the Empress, prince Eitel Friedrich, prince Adalbert, Imperial Chancellor (Reichskanzler) Prince zu Hohenlohe, the Prussian Minister of War Heinrich von Goßler, the Commander of the Expeditionary Corps, Lieutenant General von Lessei, and the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Bernhard von Bülow.[6]

During the inspection, the Emperor delivered farewell remarks – the Hun speech as it was soon to be known – to the departing Corps and surrounding spectators, which were said to number a few thousand. After the speech, von Lessei thanked the Emperor for the words dedicated to his men, and a band intoned "Heil Kaiser Wilhelm Dir". At 14:00 the Batavia was the first ship to set sail for Beijing and the other two ships followed in 15 minute intervals.[6]

The text of the Hun speech has survived in several different variations. The central passage reads:

Kommt Ihr vor den Feind, so wird er geschlagen, Pardon wird nicht gegeben; Gefangene nicht gemacht. Wer Euch in die Hände fällt, sei in Eurer Hand. Wie vor tausend Jahren die Hunnen unter ihrem König Etzel sich einen Namen gemacht, der sie noch jetzt in der Ueberlieferung gewaltig erscheinen läßt, so möge der Name Deutschland in China in einer solchen Weise bekannt werden, daß niemals wieder ein Chinese es wagt, etwa einen Deutschen auch nur scheel anzusehen.

If you come before the enemy, he will be defeated! No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands is forfeited! Just as a thousand years ago the Huns under their king Etzel made a name for themselves, one that even today makes them seem mighty in history and legend, so may the name Germany be affirmed by you in such a way in China that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German!

Textual tradition and versions

The speech was delivered freely by Wilhelm II. No manuscript of it has survived and one may never have existed. Several versions of the speech are known:

- Wolffs Telegraphisches Bureau ("WTB I") circulated a summary of it in indirect speech on 27 July 1900 (22:30). It contained no reference to the Huns and did not mention giving no quarter to the Chinese.[9][10]

- On 28 July 1900 (01:00) a second version of the speech was circulated by Wolffs Telegraphisches Bureau (WTB II), which was published by the Deutscher Reichsanzeiger in its non-official section. In this variation, the reference to the Huns is again missing. According to this variant, the Emperor said "No quarter will be given. Prisoners will not be taken", which may also be understood as alluding to the behaviour of the Chinese.[11][5]

- A number of journalists from local North German newspapers were present at the speech and took down the spoken word of the Emperor in shorthand. Apart from minor listening, recording or typesetting errors, these transcripts produce a consistent wording of the speech. In 1976, Bernd Sösemann consolidated the versions published on 29 July 1900 in the Weser-Zeitung and the Wilhelmshavener Tageblatt. This consolidated version is today considered to be authoritative.[12] It contains the passage quoted above.

Interpretation

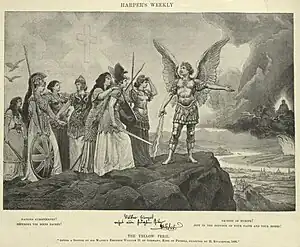

With the Hun speech, Wilhelm II called on the German troops to wage a ruthless campaign of revenge in China.[13] When giving the speech, Wilhelm II especially wanted his soldiers to avenge the assassination of Clemens von Ketteler, the German envoy to China, on 20 June 1900.[14] In an earlier dispatch of 19 June 1900 to Bernhard von Bülow, Wilhelm II had already demanded that Beijing be levelled to the ground and called the coming fight a "battle of Asia against all Europe".[2] At the same time, Wilhelm II had donated the painting Völker Europas, wahrt eure heiligsten Güter (Peoples of Europe, protect your most sacred possessions) to several troop transports to China.[15] The painting is considered to be an allegory of the defence of Europe under German leadership against the alleged "Yellow Peril", which had had long been a cause for worry for the Emperor.[2] A 1895 sketch by Wilhelm II had in fact been the inspiration for the painting by Hermann Knackfuß.[2]

In today's academic interpretation of the speech, Thoralf Klein argues that the scandalous effect of the Hun speech consists, on the one hand, in its explicit call to break international law and, on the other hand, in its blurring of the boundaries between "barbarism" and "civilisation".[16] The call to break international law can be seen in the demand to give no quarter to the Chinese. To declare that no quarter will be given was explicitly prohibited by Article 23 of the Hague Land Warfare Convention (Laws and Customs of War on Land [Hague II] of 29 July 1899), a convention signed by the German Empire, but not by Qing China, which had only participated in the Hague Peace Conference.[17] The blurring of the lines between "civilisation" and "barbarism" becomes manifest when the "barbarian" Huns were chosen by Wilhelm II as the role model for the departing German troops, the same German forces which were sent by Wilhelm II to fight in the name of "civilisation" against China's supposed relapse into "barbarism".[16]

Reactions and consequences

The soldiers who left for China took their emperor literally. This is how a non-commissioned officer reported the speech in his diary:

Es dauerte nicht lange bis Majestät erschien. Er hielt eine zündende Ansprach an uns, von der ich mir aber nur die folgenden Worte gemerkt habe: "Gefangene werden nicht gemacht, Pardon wird keinem Chinesen gegeben, der Euch in die Hände fällt."

It was not long before His Majesty appeared. He made a stirring speech to us, of which I only remembered the following words: "No prisoners will be taken, no quarter will be given to any Chinese who fall into your hands."

— Heinrich Hasline[18]

After the speech, German soldiers marked the railway wagons that transported them to the coast with inscriptions such as "revenge is sweet" or "no quarter".[19] And the letters of the German soldiers reporting on excesses during their mission in China, which were later printed in German newspapers, were called "Hun letters".[20]

With the Hun speech, Wilhelm II met with approval at home and abroad, but also with criticism. Of the persons present at the speech, Bernhard von Bülow argued in his 1930 memoirs that it was "the worst speech of that time and perhaps the most disgraceful speech that Wilhelm II [had] ever given".[21][22] The Prince of Hohenlohe on the other hand remarked in his journal of that day, that it had been a "sparkling speech".[23]

In contemporary German public debate, the liberal German politician and Protestant pastor, Friedrich Naumann – a member of the Reichstag – vigorously defended the Emperor and stated that he thought that "all this squeamishness is wrong" and argued that no prisoners should be taken in China.[24] This defence earned him the nickname "Hun priest" (Hunnenpastor).[24] On the other hand, Eugen Richter, a fellow liberal member of the Reichstag, heavily criticized the speech in a Reichstag debate on 20 November 1900 and stated that the speech did "not correspond to Christian conviction."[25]

Source of the "Hun" epithet

The "Hun speech" had a great impact during the First World War, when the British took up the "Hun"-metaphor and used it as a synonym for the Germans and their behaviour, which was described as barbaric. For a long time, the speech was considered to be the source of the epithet (ethnophaulism) "the Huns" for Germans. This view was for example held by Bernhard von Bülow,[26] but it no longer reflects the state of academic debate, as the "Hun"-stereotype had already been used during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871).[27][28]

Audio recording

In 2012 an Edison-wax cylinder phonograph was discovered containing a recording of the slightly abridged second version of the speech (WTB II) from the turn of the 20th century.[29] Whether this recording was voiced by Wilhelm II himself remains disputed.[30] A voice comparison carried out by a member of the Bavarian State Office of Criminal Investigation (Bayerisches Landeskriminalamt) could not unequivocally confirm the speaker as Wilhelm II.[29]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dabringhaus 1999, p. 461.

- 1 2 3 4 Röhl 2017, p. 74.

- ↑ Klein 2013, p. 164.

- ↑ de Quesada & Dale 2013, p. 23.

- 1 2 "Nichtamtliches. Deutsches Reich. Preußen. Berlin, 28. Juli". Deutscher Reichsanzeiger (in German). No. 178. 28 July 1900. p. 2. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Sösemann 1976, pp. 342–343.

- ↑ Sösemann 1976, p. 350.

- ↑ Dunlap.

- ↑ Sösemann 1976, p. 344.

- ↑ "Deutsche Kulturkämper". Norddeutsches Volksblatt: Organ für die Interessen des werktätigen Volkes (in German). No. 175. 31 July 1900. p. 1. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ↑ Sösemann 1976, p. 345.

- ↑ Sösemann 1976, pp. 348–350.

- ↑ Röhl 2017, p. 76.

- ↑ Röhl 2017, p. 75.

- ↑ Röhl 2017, p. 77.

- 1 2 Klein 2013, p. 171.

- ↑ Klein 2013, p. 168.

- ↑ Wünsche 2008, p. 201.

- ↑ Sösemann 2007, p. 120.

- ↑ Ladendorf 1906, p. 130.

- ↑ Bülow 1930, p. 359: "Die schlimmste Rede jener Zeit und vielleicht die schädlichste, die Wilhelm II. je gehalten hat, war die Rede in Bremerhaven am 27. Juni 1900".

- ↑ Clark 2000, p. 170.

- ↑ zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst 1931, p. 579.

- 1 2 Raico 1999, p. 232.

- ↑ Richter, Eugen (20 November 1900). "Eugen Richter zur Hunnenrede Wilhelms II". Eugen-Richter-Institut. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ↑ Bülow 1930, p. 361: "Wenn das gute und edle deutsche Volk, das im besten Sinne humaner denkt und fühlt als irgendein anderes Volk in beiden Hemisphären, von Millionen 'the huns', 'les huns', 'die Hunnen' genannt wurde, so war das eine Folge jener unseligen Rede, die Wilhelm II. in Bremerhaven gehalten hatte.".

- ↑ Klein 2013, p. 174.

- ↑ Musolff 2017, pp. 108–110.

- 1 2 Schmitz 2012.

- ↑ "Hunnenrede auf Wachswalze: Tonaufnahme der Rede Wilhelms II. gefunden". Bayerischer Rundfunk (in German). 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

Bibliography

- Bülow, Bernhard von (1930). Denkwürdigkeiten (in German). Vol. I [Vom Staatssekretariat bis zur Marokko-Krise]. Berlin: Ullstein.

- Clark, Christopher (2000). Kaiser Wilhelm II. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315843308. ISBN 9781317891468.

- Dabringhaus, Sabine (1999). "An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900–1901". In Boemeke, Manfred F.; Chickering, Roger; Förster, Stig (eds.). Anticipating Total War: The German and American Experiences, 1871–1914. Cambridge University Press. pp. 459–476. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139052511. ISBN 9781139052511.

- Dunlap, Thomas. "Wilhelm II: "Hun Speech" (1900)". German History in Documents and Images (GHDI). Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, Chlodwig (1931). Denkwürdigkeiten der Reichskanzlerzeit (in German). Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlangsanstalt.

- Klein, Thoralf (2013). "Die Hunnenrede (1900)". In Zimmerer, Jürgen (ed.). Kein Platz an der Sonne: Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte (in German). Campus Verlag. pp. 164–176. ISBN 9783593398112.

- Ladendorf, Otto (1906). "Hunnenbriefe". Historisches Schlagwörterbuch (in German). De Gruyter. p. 130. doi:10.1515/9783111496207. ISBN 9783111496207.

- Musolff, Andreas (2017). "Wilhelm II's 'Hun Speech' and Its Alleged Resemiotization During World War I" (PDF). Language and Semiotic Studies. 3 (3): 42–59. doi:10.1515/lass-2017-030303. S2CID 158768449.

- de Quesada, Alejandro; Dale, Chris (2013). Imperial German Colonial and Overseas Troops 1885–1918. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781780961651.

- Raico, Ralph (1999). "Friedrich Naumann – ein deutscher Modelliberaler?". Die Partei der Freiheit: Studien zur Geschichte des deutschen Liberalismus (in German). Oldenbourg: De Gruyter. pp. 219–261. doi:10.1515/9783110509946. ISBN 9783110509946.

- Röhl, John C. G. (2017). "The Boxer Rebellion and the Baghdad railway". Wilhelm II: Into the Abyss of War and Exile, 1900–1941. Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–95. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139046275. ISBN 9781107544192.

- Schmitz, Rainer (13 November 2012). "Sensationelle Tonaufnahme: Spricht da Kaiser Wilhelm II.?". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- Sösemann, Bernd (1976). "Die sog. Hunnenrede Wilhelms II.: Textkritische und interpretatorische Bemerkungen zur Ansprache des Kaisers vom 27. Juli 1900 in Bremerhaven". Historische Zeitschrift (in German). 222 (1): 342–358. doi:10.1524/hzhz.1976.222.jg.342. S2CID 165100470.

- ———————— (2007). "'Pardon wird nicht gegeben!' Staatliche Zensur und Presseöffentlichkeit zur 'Hunnenrede'". In Leutner, Mechthild; Mühlhahn, Klaus (eds.). Kolonialkrieg in China: die Niederschlagung der Boxerbewegung 1900–1901 (in German). Ch. Links Verlag. pp. 118–122. ISBN 9783861534327.

- Wünsche, Dietlind (2008). Feldpostbriefe aus China: Wahrnehmungs- und Deutungsmuster deutscher Soldaten zur Zeit des Boxeraufstandes 1900/1901 (in German). Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 9783861535027.

External links

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Hunnenrede

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Hunnenrede