| Hungarian Civil War (1264–1265) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Duke Stephen is crowned by his father, Béla IV (from the Illuminated Chronicle) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Forces loyal to Béla IV | Forces loyal to Stephen | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

King Béla IV Duchess Anna of Macsó Duke Béla of Macsó Henry Kőszegi Lawrence Matucsinai Ernye Ákos Henry Preussel Ladislaus Kán Julius Kán † Menk |

Younger King Stephen Peter Csák Matthew Csák Michael Rosd Job Záh Panyit Miskolc Alexander Karászi Mikod Kökényesradnót Stephen Rátót Reynold Básztély | ||||||

The Hungarian Civil War of 1264–1265 (Hungarian: 1264–1265. évi magyar belháború) was a brief dynastic conflict between King Béla IV of Hungary and his son Duke Stephen at the turn of 1264 into 1265.

Béla's relationship with his oldest son and heir, Stephen, became tense in the early 1260s, because the elderly king favored his daughter Anna and his youngest child, Béla, Duke of Slavonia. Stephen accused Béla of planning to disinherit him. After a brief skirmish, Stephen forced his father to cede all the Kingdom of Hungary's lands east of the Danube to him and adopted the title of junior king in 1262. Nevertheless, their relationship remained tense, causing a civil war by the end of 1264. The conflict resulted in Stephen's victory over his father's royal army. They concluded a peace treaty in 1266, which failed to restore confidence between them. Béla died in 1270. The 1264–1265 civil war was one trigger for the emerging feudal anarchy in Hungary by the last decades of the 13th century.

Sources seldom mention the civil war. Letters of donation and superficial hints from Hungary, Austrian chronicles and annales briefly record some events without context. Consequently there are several historiographical reconstructions of the chronology of the civil war. This article follows the most accepted reconstruction of the events compiled by historian Attila Zsoldos in his work, the only monograph about the conflict between Béla IV and Stephen.

Background

Social changes

When Béla IV ascended the Hungarian throne in 1235, he declared his principal purpose was "the restitution of royal rights" and "the restoration of the situation which existed in the country" during the reign of his grandfather, Béla III. He set up special commissions, which revised all royal charters of land grants made after 1196. The monarch's annulment of former donations alienated many of his subjects from him.[1]

The First Mongol invasion of Hungary (1241–1242) devastated much of the Kingdom of Hungary. This devastation was especially heavy in the plains east of the Danube, where at least half of the villages were depopulated. Preparation for a new Mongol invasion was the central concern of Béla's policy.[2] In a 1247 letter to Pope Innocent IV, Béla announced his plan to strengthen the Danube with new forts.[3] He abandoned the ancient royal prerogative to build and own castles, promoting the construction of nearly 100 new fortresses by the end of his reign.[4] Béla made land grants in the forested regions. In return, the new landowners were obliged to equip heavily armoured cavalrymen to serve in the royal army. To replace those who perished during the Mongol invasion, Béla IV promoted colonisation. Germans, Moravians, Poles, Ruthenians and other "guests" arrived from neighbouring countries and were settled in depopulated or sparsely populated regions. He also persuaded the Cumans, who left Hungary in 1241, to return and settle on the plains along the river Tisza.[5]

Tense relationship

King Béla's eldest son Stephen was born in 1239. A royal charter of 1246 mentions Stephen as "King, and Duke of Slavonia". Apparently, in the previous year, Béla had his son crowned as king, proclaiming him as his heir apparent. He endowed Stephen with the lands between the river Drava and the Adriatic Sea. Since 1245, young Stephen nominally ruled the provinces of Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia.[6][7] When Stephen attained the age of majority in 1257, his father appointed him Duke of Transylvania. Stephen's rule there was short-lived, because his father transferred him to Styria in 1258.[8] His rule remained unpopular in Styria. With support from King Ottokar II of Bohemia, the local lords rebelled against the Hungarian administration. Although Stephen achieved important successes during the war in Bohemia, in the decisive Battle of Kressenbrunn King Béla's and Stephen's united army was vanquished on 12 July 1260, primarily because the main forces under Béla's command arrived late.[9] Stephen, who commanded the advance guard, barely escaped from the battlefield.[10] The Peace of Vienna, which was signed on 31 March 1261, ended the conflict between Hungary and Bohemia, forcing Béla IV to renounce of Styria in favour of Ottokar II.[9] Stephen returned to Transylvania and ruled it for the second time after their departure from Styria.[9]

Stephen's relationship with Béla IV deteriorated in the early 1260s.[11] Stephen's charters reveal his fear of being disinherited and expelled by his father.[11] In his subsequent charters, the duke claimed he "suffered severe persecution undeservedly from his parents", who wanted to chase him "as an exile beyond the borders of his land (terra)" or "country" (regnum).[11] He also accused some unnamed barons of inciting the old monarch against him.[11] The cause of their confrontation is highly uncertain. Historian Attila Zsoldos emphasised that Béla's youngest namesake son was made Duke of Slavonia in 1260.[8][9] Traditionally, since the second half of the 12th century, the Duke of Slavonia was considered the heir apparent to the Hungarian throne.[12] Because of the emerging tensions between the monarch and his elder son, Stephen accused his father of planning to disinherit him in favour of his younger brother, eleven-year-old Béla.[13]

According to several historians, including Gyula Pauler and Jenő Szűcs, the young Béla's appointment as Duke of Slavonia was the reason that the relationship between father and son deteriorated.[14][15] In contrast, Zsoldos considered Béla's appointment was the consequence of their tense relationship, not the root cause.[13] Jenő Szűcs argued that Béla IV – who attempted to restore royal authority and revise his predecessors' land grants in Hungary – strongly opposed Stephen's generous donations to his own partisans (for instance, Denis Péc) in Styria, which strained their relationship. According to Szűcs, the monarch tried everything to protect the proportion of royal estates in Slavonia.[15] Attila Zsoldos considered the defeat at Kressenbrunn one of the major reasons for the deterioration of the relationship. After initial successes, Béla arrived. His mistakes in battle led to the Hungarians suffering a major defeat. Stephen, severely injured as a result, barely escaped. Zsoldos assumed a possible fierce confrontation took place between Béla and Stephen after the battle.[10] Throughout his reign, Béla IV was "far from the ideal of warrior-king", according to Romanian historian Tudor Sălăgean.[16] Even the Illuminated Chronicle notes that Béla "was a man of peace, but in the conduct of armies and battles the least fortunate" when narrating Béla's defeat in the Battle of Kressenbrunn.[10] In contrast, the ambitious Duke Stephen "possessed all the qualities needed to become an exceptional military commander" (Sălăgean). According to Sălăgean, Stephen, who represented a "late medieval chivalry", could select appropriate combat-capable accompaniment from the young members of lesser noble families (e.g. Reynold Básztély, Egidius Monoszló and Mikod Kökényesradnót). With his donations, Stephen established a new political and military elite, which opposed the old aristocratic families centred around King Béla IV and Queen Maria Laskarina.[16] Stephen strived to establish an independent government in Transylvania, filling positions with his partisans. Shortly after his arrival, he dismissed Ernye Ákos – his father's faithful baron – as Voivode of Transylvania.[17] Gyula Kristó emphasised the social base of the two kingdoms as the main factor behind the conflict, instead of the personal contrast between father and son. According to Kristó, Stephen turned against his father under pressure from his own confidants and supporters, who wanted to take control of the country from the old elite.[18] Showing another aspect, Zsoldos considered Stephen was transferred from Slavonia to Transylvania because of the danger of a possible Mongol invasion at the turn of 1259 and 1260; this may show Béla actually respected his son's military abilities.[10] Their relationship was not yet irreversibly bad in 1261: Stephen and his father jointly invaded Bulgaria and seized Vidin that year.[19]

1262 civil war and division of the kingdom

Jenő Szűcs emphasised that Stephen, as Duke of Transylvania, began using the denotation "dei gratia" (by the Grace of God) arbitrarily before the list of his titles, which was used exclusively by the reigning kings in Hungary. Stephen also extended his authority along the river Tisza beyond Transylvania at the turn of 1261 and 1262. The Cumans living there were considered his subjects.[20] Stephen's charters prove he made land grants in Bihar, Szatmár, Bereg, Ugocsa, and other counties situated outside Transylvania.[21] His solid position in the region was well reflected by the fact that the Diocese of Várad (Oradea Mare) saw fit to confirm a March 1261 donation letter of Béla IV with Stephen in September 1262.[22] Several local nobles and county authorities during their acquisitions and judgments, respectively, already followed the same method before 1262.[21] There were signs of an escalation of the conflict by that time: for instance, when the royal couple – Béla and Maria – visited the Slavonian province in the spring of 1262, the monarch confiscated Medvedgrad from the Diocese of Zagreb to transfer the crown jewels and royal treasures there from Székesfehérvár for safekeeping and to protect them from Stephen.[23]

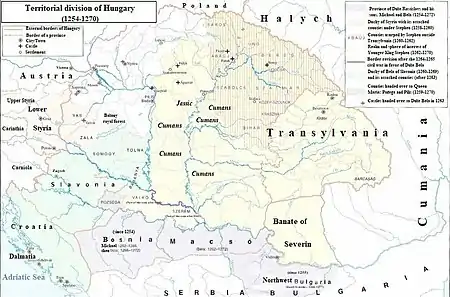

Following a series of violations between their partisans, an armed conflict or civil war broke out between Béla IV and Stephen in the autumn of 1262. It is plausible that Stephen, whose army marched into the western part of Upper Hungary (Bars and Pozsony counties), was the one who initiated the war. According to Queen Maria's undated charter, Béla and Stephen "faced each other, armies on both sides, ready to raise their hands to each other", so it is conceivable no serious acts of war took place. Szűcs considered the two armies met perhaps around November 1262 near the castle of Pressburg (present-day Bratislava, Slovakia).[20] After the intervention of the representatives of local secular and church authorities, ispán (count) Herrand Héder and Ladislaus, the archdeacon of Hont, respectively, a truce was secured between the parties.[24] They concluded a peace treaty there around 25 November 1262 with the mediation of the two archbishops of the realm, Philip Türje of Esztergom and Smaragd of Kalocsa, in addition to the attendance of Philip, Bishop of Vác, Benedict, Provost of Szeben and John, Provost of Arad. According to the Peace of Pressburg, Béla IV and Stephen divided the Kingdom of Hungary along the Danube: the lands to the west of the river remained under the direct rule of Béla, and Stephen took over the government of the eastern territories. He also adopted the title of younger king (Latin: rex iunior).[24][25] On 5 December 1262, Stephen issued a charter in Poroszló: he declared he was satisfied with all that his father had given him in the agreement reached in Pressburg "some days ago" and promised that he would not make further demands. He undertook not act against his father or his younger brother, Duke Béla. He admitted he took over the castle of Fülek (present-day Fiľakovo, Slovakia,) together with its accessories in accordance with the peace treaty with Béla IV. Stephen also promised that he would return all landholdings and properties which he took from his father's barons and servants during the war, except persons mentioned by name (Henry Preussel and Franco, the captains of Fülek, who refused to hand over the fort to Stephen, despite the agreement).[22] Béla IV promised simultaneously he would not encourage the Cumans to join his allegiance. Stephen did the same regarding the German and Slav subjects in Slavonia, as well as the Bohemian mercenaries in Béla's royal army. They also agreed they would never retaliate against the nobles and royal servants in the service of the other party and would never infringe on their properties. In addition, Transylvanian salt mining and trade were placed under the administration of both sovereigns.[23][26]

Tudor Sălăgean argued Stephen's victory was overwhelming and with the Cumans under his suzerainty, he commanded the largest number army in Hungary.[27] His domain or realm ("kingdom") extended to Sáros, Újvár, Gömör, Borsod and Nógrád counties, in addition to the Torna lordship, in north-western direction from Transylvania.[28] In the south, his realm extended to the frontier with the Kingdom of Serbia (Bács, Valkó and Syrmia counties). He also governed whole Transylvania,[29] despite previous historiographical claims that his suzerainty did not cover the region of Burzenland (Barcaság).[30]

Preparing for war

Stephen was completely satisfied with his new acquisitions. In May 1263, he promised he would not persecute the lords who joined his father. He also suggested that if a sinner flees from one kingdom to another, the ruler of the latter could also hold him accountable under the verdict.[31] He asked the two archbishops to submit the Peace of Pressburg to the Holy See in July 1263.[29] There is no sign Pope Urban IV confirmed the treaty, however, because Béla IV refused to involve the church in the peace process, despite papal legate Velasco's arrival in Hungary.[32][33] Stephen established a separate royal court, nominating his own partisans to important positions in his household at Transylvania. The voivode (military leader) of Transylvania (Ladislaus Kán) and the ban of Severin (Lawrence Igmánd) belonged to his allegiance. Béla IV had absolutely no authority in these frontier regions.[34] Stephen's ledger from the first half of 1264 is preserved. The ledger contains his donations, gifts and cash benefits given to his supporters (for instance, Egidius Monoszló, Reynold Básztély, Joachim Gutkeled, Dominic Csák and the Cumans). Entries reflect the younger king tried to attract his followers spasmodically on the eve of the 1264–1265 civil war.[35] He financed these expenses from the income of the mintage in Syrmia, salt storage in Szalacs (today Sălacea, Romania) and the silver mining in Selmec (today Banská Štiavnica, Slovakia).[36]

However, Béla IV and his partisans saw the 1262 peace and division of Hungary as a temporary setback. They embarked on a massive diplomatic and propaganda campaign aimed at undermining Stephen's positions and prepared for armed retaliation.[27] Several landholdings of members of the royal family lay in Stephen's newly established domain. For instance, Béla's daughter, Duchess Anna of Macsó and her husband Rostislav Mikhailovich possessed the Bereg royal lordship. After the division, Stephen's wife Elizabeth the Cuman acquired the lordship. Queen Maria and Duchess Anna protested the occupation of their lands in the papal court. Anna's sons, Michael and Béla, accused Stephen of confiscating their castles – Bereg (Munkács) and Füzér – violating the 1262 Treaty of Pressburg, which, according to Zsoldos, was incapable of resolving the dynastic conflict.[37] Instead of reconciliation, Béla IV gathered strength to retaliate. He granted the castle of Visegrád with the ispánate (court) of Pilis' royal forest and Požega County to his queen consort, Maria. The monarch handed over the castles of Nyitra (Nitra, Slovakia), Pressburg (Bratislava, Slovakia), Moson and Sopron to his youngest son, Duke Béla. In addition, the king attached the counties of Baranya, Somogy, Zala, Vas and Tolna to Béla's duchy.[38] Pope Urban IV confirmed all of the donation letters on 21 December 1263. According to a papal letter, the young Béla was also granted the castle of Vasvár and Valkó County before 15 July 1264. Valkó County belonged to Stephen's sphere of influence in accordance with the Peace of Pressburg; Béla IV violated the treaty with this donation. Pope Urban IV instructed Philip Türje and Paul Balog, Bishop of Veszprém, to defend Duke Béla's interests. At the king's request, the pope confirmed the properties of Duchess Anna (Szávaszentdemeter). Several donations concerned lands in Stephen's realm, which also violated the 1262 treaty. In this case, Béla's donations, and especially their papal confirmations, were designed to secure the future of those family members on his side against Stephen, who would succeed to the throne after his death. Stephen was unaware of these.[39] In 1263, he sent reinforcements under the command of Ladislaus Kán to Bulgaria to support Despot Jacob Svetoslav against the Byzantine Empire. A diplomatic mission around the same time prevented a Mongol invasion.[40]

In addition, the lands owned by Béla and Stephen's confidants did not coincide with the borders of the two kingdoms, causing many conflicts. According to Jenő Szűcs, although this intersection of territorial and personal principles was not unheard of in the classical fidelity structure, it was alien to Hungarian experience and therefore created the legal conditions for the development of feudal anarchy.[41] Stephen's supporters were composed of political refugees, ambitious young men (representatives of the second generation after the Mongol invasion) and Western Transdanubian lords, who were already in his Slavonian and then Styrian courts. Szűcs argued the decade of the country's division made it possible, for the time being, for the aristocracy to prepare for the evolution of feudal factions in the spirit of crown allegiance; the dual government was the "dress rehearsal" of the era of feudal anarchy.[42] In accordance with the treaty, there were initial attempts to smooth out these disputes, such as the establishment of common courts to which both parties delegated members. Usually, only insignificant cases were discussed here. The free party choice of the lords did not prevail in practice and the noblemen accused of sin often fled to the other monarch, where they were granted asylum.[43] For instance, Béla accused Conrad Győr of counterfeiting coins. According to his royal charter, Conrad fled Béla's realm, to avoid being held accountable and joined the court of Stephen. In 1263, Conrad received amnesty from the king at the request of Stephen.[44] A notorious robber baron, Panyit Hahót also took advantage of the emerging tense relationship within the Árpád dynasty. He committed serious crimes against his neighbours in Zala County in Béla's realm. As a result, the king ordered the confiscation of his lands. In response, Panyit left Béla's realm and took an oath of allegiance to Stephen. Although a joint court of Béla and Stephen ruled against Panyit, he presented himself as a victim of a political persecution and procured a document from Duke Stephen in early October 1264, which set down the duke's promise that he would invalidate the judgment and return the confiscated lands to Panyit after his accession to the Hungarian throne. Stephen Rátót also left the royal court and defected to Duke Stephen in 1264, because of his fear following the dismissal and imprisonment of Csák from the Ugod branch of the gens (clan) Csák. After his departure, Béla devastated Stephen Rátót's landholdings in his realm.[41]

Movements in the opposite direction, however, were more common within the elite. Throughout 1263 and 1264, a number of Stephen's important followers left his court and swore allegiance to Béla as a result of the old monarch's intrigues and tactics.[27] Béla successfully convinced the Cumans to join his domain,[45] despite the younger king's desperate attempts to avoid this. Stephen's ledger shows he donated textiles worth 134 marks to them.[46] Ladislaus Kán and his brother Julius Kán also changed their allegiance to the Hungarian monarch just prior to the outbreak of civil war.[27][47] Denis Péc and his vice-chancellor Benedict were also notable defectors around the same time.[47][45] Benedict's departure was a painful point in Stephen's administration: one of his creditors, Syr Wulam compiled a list of his financial claims concerning transactions carried out in the time of Benedict, so that he would not have to suffer losses as a result of the impending political storm.[48] Furthermore, Béla IV exerted his external influence and was offered more support from his sons-in-law in the dukedoms of Poland, dukes Bolesław V the Chaste and Bolesław the Pious, in addition to Leszek II the Black.[49] Recognising the strategic military importance of the Buda Castle he built after the Mongol invasion, Béla IV decided to suspend the town privileges of his capital Buda, including the free election of the burghers' magistrate. As a result, he dismissed his villicus (steward), Peter, after 11 September 1264. He appointed his faithful confidant, Austrian knight Henry Preussel, as the first rector of Buda; he also became commander and castellan of the fortress.[50] The entire royal family, including Duke Stephen were present at the wedding of Duke Béla and Kunigunde of Ascania near Pressburg on 5 October 1264,[51] under the patronage of Ottokar II of Bohemia, who was considered the strong ally of Béla IV after 1261.[52] Sălăgean argued the wedding meant the complete external isolation of Stephen.[52] According to historian Attila Zsoldos, Béla IV – having secured himself on several fronts – confronted his elder son at the event, which made a large-scale civil war in Hungary inevitable.[53]

Reconstruction of the events

Béla's attack on two fronts

The civil war broke out around 10 December 1264. Brothers Ladislaus and Julius Kán led Béla's army, which consisted mostly of Cuman warriors. They invaded Duke Stephen's realm and pushed forward unhindered penetrating to the valley of the Maros (Mureș) river in the southern part of Transylvania,[54][55] despite the failed efforts of Alexander Karászi to regain these territories.[56] Stephen's army – the younger king was present in person, along with Peter Csák and Mikod Kökényesradnót – stopped their advance at the Fortress of Déva (Deva, present-day Romania), where the invaders suffered a heavy defeat, and Julius Kán was killed.[55] It was the first battle where Peter Csák – a prominent combatant of the 1270s internal conflicts – could show his brilliant military talent, effectively leading Stephen's army at Déva.[54][57] Attila Zsoldos emphasised Stephen was able to set up an efficient army against his father, which took time to reach the southern parts of his domain. Thus, the assembly point could have been in a central location – possibly Várad. Just before the Kán brothers' attack, Stephen began to gather his army and left his family – Queen Elizabeth, his four daughters and the infant son Ladislaus – behind the fortified walls of Patak Castle in Zemplén County (today in ruins near Sátoraljaújhely). Stephen intended to launch an attack against Béla's kingdom, but his father dealt a pre-emptive blow.[55] After the interrogation of the prisoners of war and reconnaissance reports, however, it became clear to Stephen that the Cuman army was only an advance force followed by the much more significant royal army led by the skilled military general, Judge royal Lawrence, son of Kemény (or Matucsinai). His troops followed the same route in the kingdom's south forcing Stephen to retreat as far as the castle at Feketehalom (Codlea, Romania) in the easternmost corner of Transylvania.[58][59][60] Zsoldos believed Stephen retreated without fighting Lawrence's advancing army because of simultaneous events in the northern part of his realm.[25][61]

Simultaneously with the military events in the Maros valley, another royal army crossed the border from the Szepesség region (Spiš) on the shortest route to the northeast under Duchess Anna's command in Upper Hungary.[62] Attila Zsoldos believed Palatine Henry Kőszegi acted as the actual general of the royal troops under the nominal command of Duchess Anna, which consisted of the northern corps of Béla's royal army during the civil war. Zsoldos argued Lawrence's military manoeuvre in the south served as a diversion to entice Stephen's army at a great distance. In the middle of December 1264, Duchess Anna and Henry Kőszegi's army – after some resistance – occupied the fort at Patak left defenceless and captured Stephen's consort, Elizabeth the Cuman, and their five minor children, Catherine, Mary, Anna, Margaret and the only son Ladislaus. Stephen's family were transferred to Turóc Castle (also known as Znió or Zniev, present-day near Kláštor pod Znievom, Slovakia), in the realm of Béla IV, guarded by Andrew Hont-Pázmány on orders from Duchess Anna who most fervently opposed her brother's aspirations.[63] She aimed to recover her confiscated properties in the region, mostly in Bereg and Újvár counties.[54] The capture of Stephen's family created a potential opportunity for Béla IV to extort his son, if he had been defeated on the battlefield during the war.[63]

While a smaller detached army with Duchess Anna continued advancing eastward to seize and recover her formerly confiscated estates and forts in the Bereg region (including Baranka Castle), most of the army led by Henry Kőszegi began to besiege Stephen's castles in the eastern part of Upper Hungary. This resulted in quick victories for Kőszegi. In a charter from 1270, Stephen himself mentions that during this period "almost all our castles [...] were handed over by our traitors, who believed to be faithful [...] to our parents". For instance, Béla's troops occupied the castle of Ágasvár, a small fort in the mountain range of Mátra in Nógrád County, almost without resistance because of the "unbelief and unfaithful negligence" of Job Záh, the Bishop of Pécs, who surrendered. A charter of 1346 reveals that the castle of Pécs was also occupied under Bishop Job, probably by followers of Béla IV in a later phase of the war. This, however, is not closely related to military events. Job was captured and imprisoned.[63] A certain Bács (Bach) – brother of ispán Tekesh – also handed over the castle of Szádvár in Torna County, preventing a protracted siege and opening the gates before Henry Kőszegi's advancing troops.[63]

However, another partisan, Michael Rosd, successfully defended the castle of Füzér in Újvár County and another nearby fort called "Temethyn" with a few guards, while also resisting various attempts at bribery.[63] "Temethyn" was referred to as the property of the Rosd kindred, and former historiography identified it with Temetvény Castle in Nyitra County (present-day Hrádok, Slovakia).[54] However, there are no other known landholdings of the Rosds in Nyitra County. Since they had a relatively modest fortune, as their social ascension occurred only during the reign of Stephen after 1270, their wealth could not have been enough to allow them to build a castle. Moreover, the two castles lay at an insurmountable distance from each other, which would make simultaneous protection impossible. Zsoldos identified "Temethyn", consisting of ditches and ramparts, with a recently excavated fortified outpost at the top of the Őrhegy ("Guard Hill") about one kilometre from the caste of Füzér (The word "temetvény" originally meant "embankment"). Following his success, Michael Rosd later joined Stephen's army.[64]

Prolonged siege at Feketehalom

While retreating to Feketehalom in the last days of December 1264 to prepare for a long siege,[59] Duke Stephen was informed of the capture of his family at Patak. Considering Stephen's future plausible ascension to the Hungarian throne, the "prison guard", Andrew Hont-Pázmány, did not keep the family in strict custody. For instance, he lent Elizabeth 100 silver marks during her captivity and allowed the duke's courier Emeric Nádasd to inform Stephen quickly of the fall of Patak and the house arrest of his family.[65] As a result, Stephen entrusted his faithful confidant Peter Csák with gathering a small contingent and marching into Northeast Hungary to rescue his family. Peter Csák successfully recaptured the fort of Baranka from Duchess Anna's troops, but his small army was unable to achieve further victories and could not prevent the permanent internment of Queen Elizabeth and the children in Béla's domain.[64]

.jpg.webp)

The fort of Feketehalom lay in the region in Burzenland (Barcaság) in the southeast corner of Transylvania in Stephen's realm.[58] It was fortified heavily in previous years because of fear and possible danger after a series of Mongol invasions in the region. In good condition and stocked, the small castle offered a suitable refuge for the younger king and his entourage.[66] Stephen was in a critical situation at this point, subsequently calling Feketehalom "a place of misery and death";[58] his deep apathy is clearly reflected in his later notes that "outside of God, I barely had faith in people".[67] A large number of his barons and nobles broke their allegiance to him and swore loyalty to Béla IV during that period. Even the local nobility refused to support him. During the retreat, his army dispersed gradually until only a few dozen knight remained faithful and followed their lord to the castle of Feketehalom. The Transylvanian Saxons also took an oath of allegiance to the senior king.[60] Tudor Sălăgean emphasised the concurrent adverse conditions abroad. Taking advantage of the chaotic situation in Hungary, Stephen's vassal, Despot Jacob Svetoslav, submitted himself to Tsar Constantine Tikh of Bulgaria and they crossed the Danube from the south in early 1265 and raided the Hungarian fortresses north of the river which belonged to the Banate of Severin and Stephen's realm. Furthermore, King Béla's allies in Poland – Bolesław the Pious and Leszek the Black – were embroiled in a conflict with Stephen's few external allies in the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia. Under the circumstances, the fate of the entire civil war depended on the siege of Feketehalom, according to Sălăgean.[67] Only a few dozen of Stephen's supporters followed the younger king inside the walls of the fort; for the rest of his life, Stephen did not forget their loyalty in these difficult times. With abundant donations, he enabled the social rise of his many young partisans – group of so-called "royal youth" (Hungarian: királyi ifjak, Latin: iuvenis noster) – from lesser noble, royal servant and castle warrior families. Attila Zsoldos enumerated and identified the list of known defenders (altogether 40 persons) during the siege of Feketehalom. Among them for instance, were Cosmas Gutkeled, Alexander Karászi, Dominic Balassa, Mikod Kökékenyesradnót, Demetrius Rosd, Reynold Básztély, Thomas Baksa and his young brothers (including the future illustrious military general George Baksa), Michael Csák and Thomas Káta.[68][69]

The pursuing royal army arrived at the castle of Feketehalom in the last days of 1264. The fortress was attacked first by an army vanguard led by Conrad, brother of Lawrence, the commander of Béla's army. He tried to break through the castle gate with a rapid advance, but Alexander Karászi's soldiers prevented this.[69] Initially, the defenders launched attacks attempting to drive the besiegers from under the castle wall but were unsuccessful because of the difference in both armies' numbers. Lawrence, son of Kemény, began to besiege the castle of Feketehalom with stone catapults, while the walls were guarded day and night. The attackers kept the younger king's forces under constant pressure, according to his later recollection. Stephen began to believe in the futility of resistance. It is plausible that the defenders soon exhausted their reserves. As a result, Stephen intended to send a special envoy, Demetrius Rosd, to his parents to seek mercy, but the besiegers captured him and Lawrence tortured the prisoner. Later, Duke Stephen claimed the military general intended to kill all of his enemies, while Zsoldos argued Lawrence definitely wanted to win on the battlefield.[70] However, some nobles, led by Panyit Miskolc, who were forced to enlist in the royal army during the early stage of civil war, switched allegiance and reconnoitred the besiegers' intentions, defeating them with "strength and cunning". It is possible that Panyit provided information to the defenders and sabotaged Lawrence's siege activities.[70] Formerly, Pauler and Szűcs argued Panyit arrived at the protracted siege with a rescue army and relieved the castle.[58][71] In fact, Duke Stephen's main generals, Peter and Matthew Csák led the arriving rescue army. In January 1265, they returned from Upper Hungary to Transylvania, where they collected and reorganised the younger king's army and persuaded the Saxons to return to Stephen's allegiance. The battle took place along the wall of Feketehalom between the two armies at the end of January, while Duke Stephen led his remaining garrison out of the fort. The royalist troops were defeated soundly. Lawrence was captured along with his war flags and many of his soldiers, including Thomas Kartal.[70] Andrew, son of Ivan, was the knight who lanced and speared Lawrence and three other generals (including the flag-bearer) during the battle.[72] Altogether, Alexander Karászi captured eighteen "notable knights".[70]

Stephen's road to victory

Through his victory at Feketehalom and the prior endeavours of Peter Csák, Stephen instantly regained control over Transylvania and its attached territories, Szatmár, Bereg and Ung counties, which allowed the rapid mobilisation to Northeast Hungary.[73] The victory saved Stephen from failing immediately and restored his freedom of action.[74] He decided to march into the central parts of Hungary without hesitation.[25] Stephen wanted to avoid giving his father a chance to send reinforcements to Henry Kőszegi's army. Several of his partisans joined the army along its route, including Michael Rosd,[74] Peter Kacsics with his banderium (military unit) from Nógrád County and Stephen Rátót, who administered the queenly castle folks.[58] According to Attila Zsoldos, Stephen's army marched into Hermannstadt (Szeben) then Kolozsvár (present-day Sibiu and Cluj-Napoca, Romania), before crossing the King's Pass (Hungarian: Király-hágó, Romanian: Pasul Craiului) from Transylvania to Tiszántúl ("Transtisia").[75]

Somewhere in the Tiszántúl, around the second half of February 1265, Stephen's advancing army collided with another royal army commanded by Ernye Ákos, the ispán of Nyitra County. It is plausible, because the prolonged siege of Feketehalom had failed by then, that Henry Kőszegi sent his lieutenant Ernye Ákos and his troops to conquer the area, support the besiegers and hinder Duke Stephen's counter-offensive later. Ernye sent a vanguard of Cuman warriors with its commander, chieftain Menk, which attacked the troops of Mikod and Emeric Kökényesradnót, functioning as the vanguard for Stephen's army. The Kökényesradnót brothers routed the Cumans. The main battle between Stephen's army (led by the Csák brothers) and Ernye Ákos – who was familiar with the local terrain – took place somewhere west of Várad. Ernye suffered a serious defeat and was captured. According to a royal charter, Peter Csák, who was badly wounded, defeated Ernye during a duel. Another document says his long-time rival, Panyit Miskolc, presented the fettered prisoner Ernye in the ducal court of Stephen following the clash.[75]

The victory over Ernye Ákos' army was the decisive factor for Stephen to prepare for the final assault of the civil war.[76] The army was able to penetrate the heart of the kingdom unhindered, crossing the river Tisza at the port of Várkony and marching into Transdanubia. After being informed of the defeats of Lawrence, son of Kemény, then Ernye Ákos around the same time, Henry Kőszegi suspended the conquest of castles in Upper Hungary. His army marched south near the river port at Pest to prevent Stephen's contingent from crossing, which would have been equivalent to occupying the capital. According to Jans der Enikel, a near-contemporary Austrian chronicler, Henry's army consisted of Béla IV's whole royal army, complemented by an auxiliary troop of 1,000 men led by Henry Preussel, the rector of Buda, sent to the scene by Béla's spouse, Queen Maria.[77] Duchess Anna's son, Duke Béla of Macsó, was appointed nominal general of the royal army, with his lieutenants Henry Kőszegi and Henry Preussel, but the effective leadership remained in Henry Kőszegi's hands.[76] Nevertheless, Henry Kőszegi's departure from Upper Hungary made it possible for local lords to join Stephen's advancing troops. For instance, several members of the widely extended Aba clan joined the cause, in addition to brothers Dietmar and Dietbert Apc. Stephen and his army gained a decisive victory over his father's army in the battle near Isaszeg in early March 1265.[77][78] Egidius Monoszló and Nicholas Geregye led Stephen's cavalry. Stephen was present[58][79] and led his troops on the battlefield, not only directing them but taking part in the fight. He defeated an attacking knight in a duel, while Alexander Karászi, who was on his right as a bodyguard, protected him from other attackers.[77] Béla of Macsó was able to flee the battlefield, while Henry Kőszegi was taken prisoner by the young courtly knight, Reynold Básztély, who knocked the powerful lord out of his horse's saddle with his lance and captured him on the ground.[58] Henry Preussel was also captured alive following the battle; he was executed shortly afterwards. According to Jans der Enikel's Weltchronik, Duke Stephen stabbed Preussel with a sword while the Austrian knight begged for his life. Two of Henry Kőszegi's sons, Nicholas and Ivan, were also captured. Alongside other captives, the three fettered Kőszegis were presented in Stephen's ducal court shortly after the battle.[77]

Aftermath

Peace process

Despite his decisive and indisputable victory, Stephen decided not to invade Béla's realm and remained in the territory of his domain. Only a single source, Jans der Enikel's Weltchronik claims that Stephen and his retinue entered the castle of Buda, where he negotiated with his mother, Queen Maria, before sending her to Pressburg. However, the authenticity of the narration is doubtful, because the Austrian chronicler mixes clearly identifiable events concerning Stephen's future ascension to the Hungarian throne in 1270 (for instance, the escape of Duchess Anna of Macsó with the royal treasury to the court of Ottokar II) into the narration regarding the 1264–1265 civil war.[80] Even contemporaries expected a different attitude from Stephen. Around the same time, Stephen's sister Kinga of Poland sent a letter to her niece Kunigunda of Halych (Ottokar's spouse) in Prague, in which she regretted the turn of events and lamented the sorrowful fate of her father Béla IV, who "in his bent age, when he should rest[.] [...] [H]e will be expelled from his throne, betrayed by his followers, and many of those who defend the truth of his royal majesty will die".[81] She urged her niece to intercede with her husband Ottokar II and have him provide military assistance to Béla IV.[82] According to Attila Zsoldos, Stephen showed restraint having a better bargaining position playing the role of victim, claiming moral victory for himself beside military triumph.[83] Jenő Szűcs argued this was unlikely because of the internal balance of power. Most importantly, neither Stephen nor his barons had an interest in upsetting the previous status quo.[81] In addition, Zsoldos highlighted one of the last decisions Béla IV made during the civil war. Informed of the adverse military news from the battlefields around late February 1265, the elderly monarch ordered Stephen's only son Ladislaus be sent as a political hostage from Turóc Castle to the court of Béla IV's son-in-law, Boleslaw the Chaste, Duke of Cracow in Poland. Elizabeth and the daughters remained under house arrest in the castle. This may have moderated Stephen's efforts to take full advantage of his military dominance after the Battle of Isaszeg.[65]

Both parties concluded a peace after weeks of negotiations in March 1265, again with the mediation of the two archbishops, Philip Türje of Esztergom and Smaragd of Kalocsa.[25] Béla IV sent a letter to the newly elected Pope Clement IV on 28 March 1265, to request papal confirmation of the treaty. The text of the document was not preserved. It is plausible Béla declared Stephen as heir presumptive to the Hungarian throne, while Stephen acknowledged his father as the reigning monarch of the Kingdom of Hungary. The prisoners of war were granted amnesty and freed that year. Around September 1265, still holding the dignity of Judge royal, Lawrence, son of Kemény, already appeared as an arbiter during a lawsuit.[84] In response, Queen Elizabeth and her daughters were liberated, while Ladislaus was brought home from Poland.[78] Their peace resulted in status quo ante bellum ("the situation as it existed before the war") and restoration of the 1262 Treaty of Pressburg, i.e. Béla was forced to acknowledge Stephen's suzerainty over the eastern part of Hungary (including the Cumans again). Stephen also recovered the besieged and occupied forts in Upper Hungary; he had already donated Ágasvár to his partisan Stephen Rátót in 1265. In exchange, Stephen acknowledged his younger brother Béla's right to the Duchy of Slavonia together with the later attached neighbouring counties. Stephen also abandoned his claim to administer Valkó and Syrmia counties in favour of his younger brother.[84] However, Stephen refused to return those landholdings of his family members – Queen Maria, Duchess Anna and Duke Béla of Macsó – which lay in his territory. Sometime in the spring of 1266, Stephen issued a charter, which lists his obligations to his mother. He handed over the mintage and chamber at Syrmia to her, in addition to Požega County, which she had previously possessed. According to Zsoldos, Stephen applied these guarantees not to the present, but to the period after his father's death and his accession to the Hungarian throne. However, he refused to forgive his sister Anna because of her "crime of ingratitude".[85]

Approximately one year later, their agreement was supplemented and signed in the Dominican Monastery of the Blessed Virgin on Rabbits' Island (Margaret Island, Budapest) on 23 March 1266.[25] The choice of location – beside the border between the two realms – can be linked to St. Margaret, who, as the only family member, had a more intimate relationship with her elder brother, Stephen.[86] The new treaty confirmed the division of the country along the Danube and regulated many aspects of the co-existence of Béla's regnum and Stephen's regimen (the only distinction in terminology that refers to the latter's formal subordination), including the collection of taxes and the commoners' right to free movement.[87] The document was published by both parties under the warranty of Archbishop Philip Türje (the other prelate Smaragd was murdered in the previous year). Other members of the Árpád dynasty – Queen Maria, Duchess Anna and Duke Béla of Macsó – also ratified the document.[87] Stephen made a commitment to keep the peace with his brothers-in-law Bolesław the Chaste and Bolesław the Pious.[88] The two kings also ensured Queen Elizabeth's administrative powers over the estates, which she usurped as an "heir's right" from her mother-in-law, Queen Maria, after 1262. The barons and nobles, who possessed landholdings in the territory of the other monarch, were granted complete warranty, immunity and autonomy; they owed their obligations and commitments to their own monarch, regardless of the geographical location of their estates.[87] Pope Clement IV confirmed the treaty on 22 June 1266.[87]

Ongoing strife

Following their peace, with Béla's approval, Stephen intended to punish those Cumans who had betrayed him earlier and joined the senior king's camp during the war. Béla provided his son with a royal army under the leadership of Roland Rátót, Ban of Slavonia, who was acceptable to Duke Stephen, because he did not participate in the civil war.[89] A significant number of Cumans wanted to leave Hungary, however, they were important militarily to Stephen. Around April 1266,[90] Stephen successfully persuaded them to remain in Hungary.[91] He subsequently invaded Bulgaria in the summer of 1266, as a punitive expedition for Jacob Svetoslav's betrayal and the storming of the Banate of Severin during the 1264–1265 civil war. However, the Bulgarian campaign renewed the distrust between Béla and Stephen. Following the victory over the Cumans in April, Roland Rátót and his army remained in Stephen's camp and also participated in the campaign against Bulgaria, which resulted in Jacob Svetoslav again accepting Stephen's suzerainty.[91] However, after the campaign, Roland Rátót was dismissed from his office of ban and was replaced by Henry Kőszegi around mid-1267. His estates in Slavonia were also plundered and destroyed.[92] It is highly probable Béla considered Rátót's participation in Duke Stephen's campaign against Bulgaria a misuse of power since the king gave Stephen the army only for regularising the Cuman tribes. Béla could also have been afraid that the skilled military leader, Stephen, had gathered allies among his supporters during these expeditions.[91] According to a royal document from 1270, issued by Stephen V, Roland lost Béla's confidence because of "the diatribe and accusations of his enemies" in the royal court.[93]

There are signs of another wave of desertions from Stephen's court to Béla's realm in the period between 1266 and 1268, which shows that confidence was never restored between father and son after the civil war. For instance, both Palatine Dominic Csák and Chancellor Nicholas Kán left his allegiance and swore loyalty to Béla IV in late 1266.[94] According to Jenő Szűcs, Béla IV and his two sons, Stephen and Béla together confirmed the liberties of all royal servants from their respected domains, from then on known as noblemen, in Óbuda then Esztergom in the summer of 1267. The historian saw this as a sign of reconciliation when their agreement in the previous year was still in full force.[95] In contrast, Attila Zsoldos considered, the king alone organised the meeting at Esztergom in 1267, and was merely mobilising and preparing for another war against Duke Stephen. Only Duke Béla attended the event, where – as Zsoldos claimed – the mobilised royal servants from his realm were not enthusiastic about another internal war. Instead, they demanded the monarch recognise their rights and privileges; the name of the absent Stephen was included in the charter at their request. All of the co-judges beside Béla in the assembly supported him. Accordingly, Henry Kőszegi, Lawrence, son of Kemény, Ernye Ákos (the three military generals during the civil war) and Csák Hahót, in addition to Paul Balog and Stephen Csák, members of the queenly household, were advocates of the "war party", which supported a military action against Stephen. The younger king ordered his confidant, Peter Kacsics, to strengthen and defend the castle of Hollókő around the same time, but the war eventually ceased because of the resistance of Béla's royal servants. The danger of war did not reappear until Béla's death in 1270.[96]

Jenő Szűcs considered that the permanence of the division of the kingdom not only hastened the further growth of the large estate system (oligarchy) and the acceleration of the disintegration of the royal estate organisation, but at the same time had a disruptive effect on political morality. The ideal of the "faithful baron" was marginalised as "loyalty" could be exchanged and purchased between the two royal powers, which allowed the formation of interest groups and baronial parties within the aristocrat elite.[97] Stephen pursued a separate foreign policy, independently of his father.[98] When Serbian monarch Stephen Uroš I invaded the Banate of Macsó, and Béla IV and his grandson Béla of Macsó launched a counter-attack in 1268,[99] Stephen's army did not participate in the conflict, despite some argument.[100] However, they cooperated in the post-war settlement: Stephen's firstborn daughter Catherine was given in marriage to Stephen Dragutin, the elder son and heir of King Stephen Uroš I.[100] Another double marriage alliance between Stephen and King Charles I of Sicily – Stephen's son, Ladislaus married Charles's daughter, Isabella, and Charles's namesake son married Stephen's daughter, Mary – strengthened Stephen's international position in 1269.[101] The death of Duke Béla of Slavonia occurred in the same year, which further affected the health of the ailing monarch. He gradually lost control of his country, and Stephen's confidants gained important positions in his domain.[102] On his deathbed, Béla IV requested King Ottokar II of Bohemia to shelter his wife Queen Maria, his daughter Duchess Anna (Ottokar's mother-in-law) and his partisans after his death.[101]

Chronological issues

Primary sources

Fragments of the events of the civil war are mentioned by various sources (altogether more than 50 charters, mostly royal letters of donation for loyalty and service), often without any context or temporal placement. Most of them present a pro-Stephen narrative because of the war's outcome.[103] The Hungarian chronicles – including the Illuminated Chronicle – omit mention of the dynastic conflict. Austrian chronicles and annales commemorate the war without detailing and mentioning the casus belli, and confine themselves to detailing the death of Austrian knight Henry Preussel with "laconic brevity". All of them narrate the events putting the date to 1267 or 1268.[11]

The Continuatio Claustroneoburgensis IV mentions the execution of Henry Preussel by Duke Stephen himself in 1267. Another Austrian annales, the Historia Annorum (written by Gutolf von Heiligenkreuz in the 1280s) lists the victories of Stephen during the civil war under this year too, possibly based on a donation letter from Hungary. Jans der Enikel's Weltchronik – also putting the date to 1267 – expands the circumstances of the "tragedy" of Preussel with various fictional elements and literary topos. In addition, the chronicle mentions the outcome of the decisive Battle of Isaszeg and the claim that Ottokar II of Bohemia sent auxiliary troops to provide assistance to his former rival Béla IV. One of the annales of the 15th-century, Formulary Book of Somogyvár, also mentions the civil war in a short sentence under the year 1267. Based on the Austrian chronicles, earlier Hungarian historiography – e.g. Mór Wertner – along with Austrian historian Alfons Huber initially dated the civil war to 1267.[104]

Historiography

Based on contemporary charters and documents, Hungarian historian Gyula Pauler determined the date of the civil war at the turn of 1264 and 1265 in his seminal monograph A magyar nemzet története az Árpádházi királyok alatt, Vol. 1–2 (The history of the Hungarian nation under the Árpádian kings), published in 1899. Pauler defined the beginning of March 1265 as the date of the Battle of Isaszeg, as the draft of the peace treaty between Béla and Stephen was presented to Pope Clement IV at the end of that month. A charter from February 1267 also refers to Lawrence, son of Kemény, as the incumbent Palatine of Hungary. However, during the civil war, Henry Kőszegi held this position, which rules out the war taking place in 1267. Furthermore, there are additional donation letters, which can be dated to 1265 or 1266, and were made at the chancelleries of Younger King Stephen and his wife Elizabeth the Cuman after their victory, rewarding the military service of their subjects during the war. Based on these fragments of data, Pauler considered the civil war lasted from around June 1264 to March 1265.[105] Hungarian (and Romanian) historiography subsequently accepted Pauler's reconstruction of the events.[62][57][98][54][56] Historian Attila Zsoldos, who wrote the first monograph about the civil war (2007), also accepted Pauler's results, but he placed the starting date in December 1264. Zsoldos argued the wedding of Béla of Slavonia and Kunigunde of Ascania, which both Béla IV and Stephen attended, took place in October 1264. Other sources confirm that office administration and judicial activity were still running smoothly in the autumn months throughout the Kingdom of Hungary, in both Béla and Stephen's domains.[106]

Dániel Bácsatyai, who translated and published the three annales of the Formulary Book of Somogyvár in 2019, considered that section of the first annales, which depicts events from the 13th century, the most valuable part of the entire formulary book, and accepted its reliability. The text narrates the civil war in the year 1267 in a similar manner to the Austrian chronicles. This prompted Bácsatyai to attempt to override the generally accepted chronology in accordance with the information in the chronicles and annales in his study in the journal Századok in 2020. The historian accepted Jans der Enikel's Weltchronik as reliable regarding the Hungarian events. The chronicle says the Hungarian lords – including the "well-known" Count Roland – fled the battlefield just before the skirmish took place at Isaszeg, which resulted in Béla's defeat and the subsequent execution of Henry Preussel. Bácsatyai identified this lord with Roland Rátót, who, however, resided in Slavonia throughout in 1264 and 1265. According to Bácsatyai, accepting the narration of the Weltchronik means the war could not have taken place during this period. Bácsatyai considered Roland Rátót was a well-known figure in Austria because of his role in the military campaigns against Frederick II, Duke of Austria and the subsequent Hungarian administration in Styria.[107] In addition, Bácsatyai also questioned the dates of the aforementioned diplomas and letters of donation, which seemingly support the dating of the civil war to the period 1264–1265. He attributed the dates of the diplomas remaining in the subsequent transcript to a copier error, while a date of an original royal charter (dated 1266) is incorrectly dated, because Stephen omitted to style himself as "Lord of the Cumans" ("dux Cumanorum"), the only one from this assumed year.[108] In addition, Bácsatyai argued when Panyit Miskolc was granted donations from Duke Stephen in 1265, the junior king does not refer to Panyit's involvement in the civil war, only in subsequent letters of donation (1268, 1270) – i.e. the civil war had not yet taken place at that time.[109] Bácsatyai also accepted the unique information of the Weltchronik, which suggests that Ottokar II sent 200 reinforcements right before the decisive battle at Isaszeg to support Béla IV. The historian connected this information to an inventory of an 18th-century list and extract of the documents of the Kleinmariazell Abbey; a short note in the manuscript contains a brief description of a 1267 charter, in which a certain Austrian ministerialis Gundakar von Hassbach undertook to donate his estate called Rohrbach to the monastery in case he did not return "from the Hungarian war". According to Bácsatyai, Gundakar was one of the 200 reinforcements. Bácsatyai believes one of the letters of Kinga of Poland to Ottokar's wife Kunigunda of Halych, which urges Ottokar's involvement, confirms the narration of Jans der Enikel's chronicle and its chronology (1267).[110] Altogether, Bácsatyai constructed the events as follows: there were brief skirmishes in 1262 and 1264(–1265), which the peace agreements managed to smooth out through the mediation of the pope. The large-scale civil war between Béla IV and Stephen broke out in January 1267, and the entire war took place in the first half of that year. The assembly of royal servants in Esztergom meant the end of the civil war in late summer 1267.[111]

In 2020, Attila Zsoldos criticised Bácsatyai's reconstruction of events on a number of points. He questioned the reliability of the Formulary Book of Somogyvár, pointing out that most of the entries for the 13th-century events are chronologically incorrect, thus, the year 1267 as the date of the civil war cannot be accepted as irrefutable.[112] Zsoldos criticized Bácsatyai's critical methodology with sources. While the Weltchronik is certainly an unreliable source in many cases because of its textual fictional elements, Bácsatyai credits the entry on the Battle of Isaszeg without any doubt. Zsoldos emphasised the Hungarian troops were not cowards and did not run away during the battle. All of Béla's most important generals were captured one after another during the civil war, while Bácsatyai's interpretation on Roland Rátót's assumed involvement in the civil war and the subsequent events is illogical and unrealistic.[113] Zsoldos objected to Bácsatyai's method, who "declared authentic diplomas to be erroneously dated to substantiate his interpretation", according to him.[114] Zsoldos cited another charter of Stephen's from 1265, which confirmed 1264–1265 as the years the civil war took place. The junior king commemorates that during the war, which occurred "paulo ante" ("not long before"), many barons left Stephen's allegiance, but Stephen Rátót remained faithful (Bácsatyai arbitrarily detached this charter from a series of documents relating to the civil war).[115] Analysing Bácsatyai's concept without taking the aforementioned charters into account, Zsoldos believed the chronology of events is unsustainable. If the civil war took place in the first months of 1267, Lawrence, son of Kemény, was unable to issue a document in May 1267 (as he did), because he was captured at the siege of Feketehalom and held in captivity for the rest of the war. Because of limited time, (Roland Rátót already resided in Zagreb in April 1267, while Duke Stephen prepared for war against the Cumans in June), the war would have taken place in just two to three weeks according to Bácsatyai's interpretation. Another charter issued in June 1267 also confirms that Ernye Ákos – who was also captured in the civil war – was recently involved in a lawsuit, which would have been impossible if the civil war had taken place at that time. Furthermore, Zsoldos pointed out that it would be illogical for Stephen to suspend his title of "Lord of the Cumans" in the year he intended to subjugate them, which would follow from Bácsatyai's theory. According to Zsoldos, Gundakar von Hassbach's departure to Hungary in 1267 connects to those events, when Béla IV tried unsuccessfully to prepare for another war against his son during the Esztergom meeting in the summer of that year. Austria became involved in the long-time Hungarian dynastic conflict in that year, which explains how the chronicles discuss the prolonged events under a single year (1267).[116] In response, Dániel Bácsatyai emphasised the contemporaneity of the Continuatio Claustroneoburgensis IV. Furthermore, he cited another Austrian chronicle (Continuatio Vindobonensis), which preserves the death of Preussel in the conflict between Béla and Stephen in 1267, along with many other events that actually happened then (e.g. the death of Otto III, Margrave of Brandenburg and the papal legate Guido's activity in Vienna). Bácsatyai pointed out, in terms of corpus, the Austrian chronicles are independent sources from each other, and it is unlikely that each author chose the year 1267 as a summary of previous events of the civil war.[117] Bácsatyai also considered that although the most important operations of the war took place in a few weeks, the final battle at Isaszeg took place later, around April–May 1267 (Béla IV ordered Roland Rátót's Slavonian forces to join the royal army perhaps due to his plight, when Stephen's advanced into Central Hungary).[118]

References

- ↑ Fügedi 1986, p. 115.

- ↑ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 151.

- ↑ Sălăgean 2016, p. 53.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986, p. 127.

- ↑ Kristó 1981, p. 118.

- ↑ Kristó 1981, p. 138.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 13.

- 1 2 Kristó 1979, pp. 48–49.

- 1 2 3 4 Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 157.

- 1 2 3 4 Zsoldos 2007, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zsoldos 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Kristó 1979, pp. 54–56.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, p. 16.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, p. 249.

- 1 2 Szűcs 2002, pp. 161–162.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 72.

- ↑ Sălăgean 2016, p. 73.

- ↑ Kristó 1979, p. 71.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, p. 247.

- 1 2 Szűcs 2002, p. 163.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 21–23.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 75.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 76.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 158.

- ↑ Kristó 1979, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 Sălăgean 2016, p. 77.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, p. 250.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Kristó 1979, p. 49.

- ↑ Kristó 1981, p. 140.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, p. 170.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 32.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, p. 164.

- ↑ Zolnay 1964, pp. 84, 100–102.

- ↑ Kristó 1979, p. 63.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, p. 171.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 33–36.

- ↑ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 159.

- 1 2 Szűcs 2002, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, p. 169.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 29.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, pp. 254–255.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Zolnay 1964, p. 99.

- 1 2 Pauler 1899, p. 256.

- ↑ Zolnay 1964, p. 89.

- ↑ Sălăgean 2016, p. 78.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 39.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 79.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Szűcs 2002, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 Zsoldos 2007, p. 48.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 80.

- 1 2 Kristó 1981, pp. 142–143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Szűcs 2002, p. 173.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 81.

- 1 2 Pauler 1899, p. 258.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 49.

- 1 2 Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 160.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 50–51.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 52–55.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 56.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 82.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 57–62.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 4 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, p. 260.

- ↑ Sălăgean 2016, p. 85.

- ↑ Sălăgean 2016, p. 86.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, p. 68.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 69–70.

- 1 2 Sălăgean 2016, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 71–72.

- 1 2 Pauler 1899, p. 262.

- ↑ Sălăgean 2016, p. 88.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 75.

- 1 2 Szűcs 2002, p. 174.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, p. 261.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 76.

- 1 2 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 82–84.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 85–88.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 Sălăgean 2016, p. 89.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 79.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, p. 178.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, p. 264.

- 1 2 3 Zsoldos 2007, pp. 94–98.

- ↑ Kristó 1979, p. 62.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, p. 167.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 100.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, pp. 181–185.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 104, 106–107, 109.

- ↑ Szűcs 2002, p. 176.

- 1 2 Fügedi 1986, p. 150.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 112.

- 1 2 Szűcs 2002, p. 195.

- 1 2 Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 163.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 114.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020a, pp. 1052–1057.

- ↑ Pauler 1899, pp. 535–536.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 42–46.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020a, p. 1051.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020a, pp. 1058–1061.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020a, pp. 1062–1063.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020a, pp. 1063–1066.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020a, pp. 1076–1080.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2020, pp. 1332–1334.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2020, pp. 1335–1336.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2020, pp. 1336–1339.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2020, p. 1340.

- ↑ Zsoldos 2020, pp. 1341–1344.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020b, pp. 1348–1349.

- ↑ Bácsatyai 2020b, p. 1353.

Sources

- Bácsatyai, Dániel (2020a). "IV. Béla és István ifjabb király belháborújának időrendje [The Chronology of the Civil War between King Béla IV and Younger King Stephen]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 154 (5): 1047–1082. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Bácsatyai, Dániel (2020b). "Válasz Zsoldos Attila kritikai észrevételeire [Response to the Critical Remarks of Attila Zsoldos]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 154 (6): 1345–1354. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Érszegi, Géza; Solymosi, László (1981). "Az Árpádok királysága, 1000–1301 [The Monarchy of the Árpáds, 1000–1301]". In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 79–187. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- Fügedi, Erik (1986). Ispánok, bárók, kiskirályok [Ispáns, Barons and Petty Kings]. Magvető. ISBN 963-14-0582-6.

- Kristó, Gyula (1979). A feudális széttagolódás Magyarországon [Feudal Anarchy in Hungary] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-1595-4.

- Kristó, Gyula (1981). Az Aranybullák évszázada [The Century of the Golden Bulls] (in Hungarian). Gondolat. ISBN 963-280-641-7.

- Pauler, Gyula (1899). A magyar nemzet története az Árpád-házi királyok alatt, II. [The History of the Hungarian Nation during the Árpádian Kings, Vol. 2.] (in Hungarian). Athenaeum.

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2016). Transylvania in the Second Half of the Thirteenth Century: The Rise of the Congregational System. East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages 450–1450. Vol. 37. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24362-0.

- Szűcs, Jenő (2002). Az utolsó Árpádok [The Last Árpáds] (in Hungarian). Osiris Kiadó. ISBN 963-389-271-6.

- Zolnay, László (1964). "István ifjabb király számadása 1264-ből [The Account of Younger King Stephen from 1264]". Budapest Régiségei. Budapesti Történeti Múzeum. 21: 79–114. ISSN 0133-1892.

- Zsoldos, Attila (2007). Családi ügy: IV. Béla és István ifjabb király viszálya az 1260-as években [A family affair: The Conflict between Béla IV and Junior King Stephen in the 1260s] (in Hungarian). História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete. ISBN 978-963-9627-15-4.

- Zsoldos, Attila (2020). "Néhány kritikai megjegyzés az 1264–1265. évi belháború újrakeltezésének kísérletéhez [Some Critical Remarks on the Attempt to Re-date the 1264–1265 Civil War]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 154 (6): 1331–1344. ISSN 0039-8098.