| Hurlingham Park | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| |

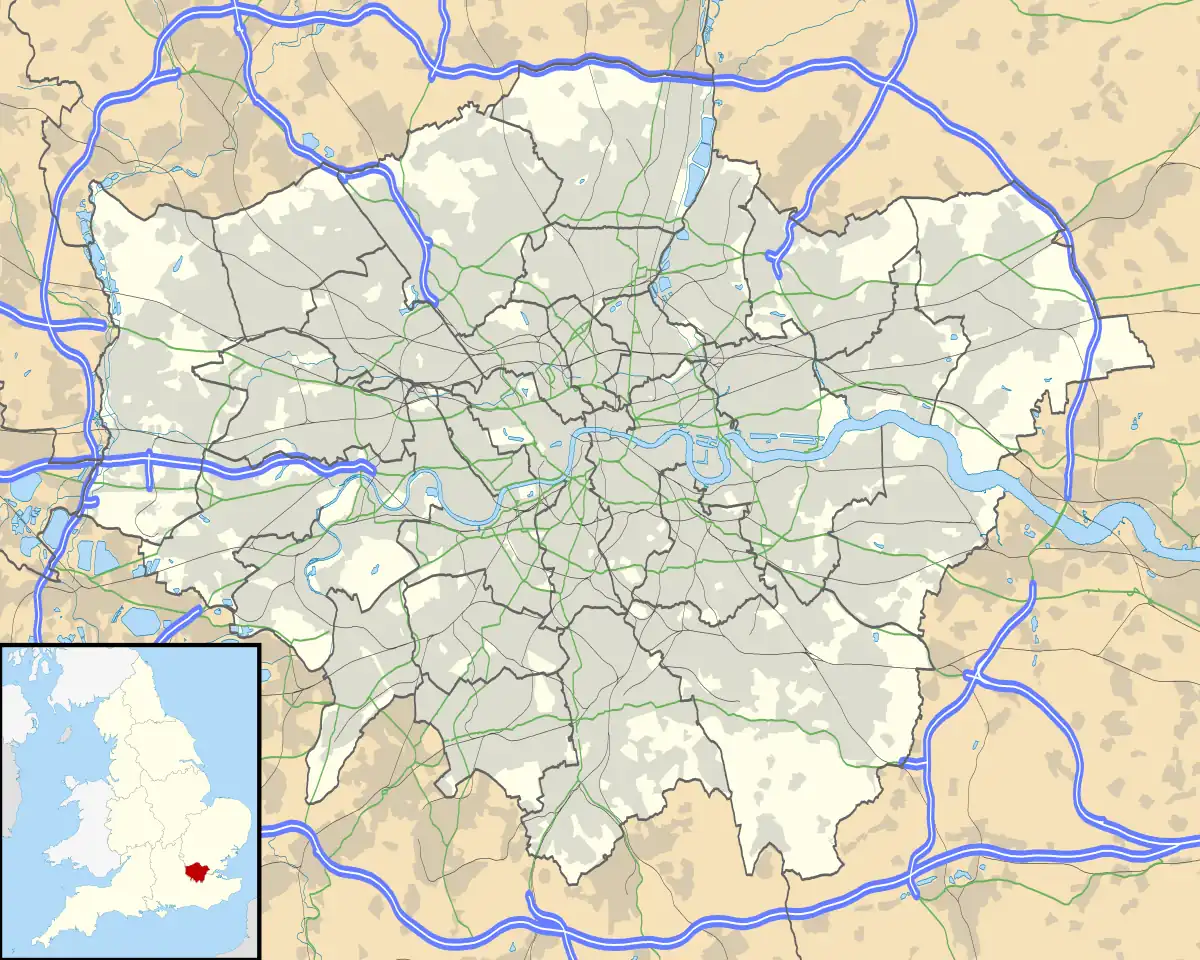

| Location | Fulham, London |

| Coordinates | 51°28′07″N 0°12′6″W / 51.46861°N 0.20167°W |

| Opened | September 11, 1954 |

| Awards | Green Flag Award |

| Website | www |

Hurlingham Park is a park and multi-use sports ground in Fulham, London, England. It is currently used mostly for rugby matches, football matches and athletics events[1] and is the home of Hammersmith and Fulham Rugby Football Club. The park is a two-minute walk from Putney Bridge tube station on the District line.[2]

Once known as the "spiritual home of British polo", Hurlingham Park was the venue for men's polo at the 1908 Olympics.[3] The park served as the location for Monty Python's Upper Class Twit of the Year sketch.[4]

Hurlingham Park received a Green Flag Award for 2013–2014.[5]

History

Polo was first played at Hurlingham Park in 1874,[2] and has been called "the spiritual home of British polo".[6] It continued to be played on the site for 65 years, until the grounds were requisitioned by the government during the Second World War.[2] The No. 1 polo ground was turned into allotments to grow food in 1939.[7][3][8]

Much of the surrounding area was compulsorily purchased by Fulham Borough Council in the 1950s to create the public park, the sports arena, and council housing.[7][9] The Hurlingham Club was subsequently left with its clubhouse, tennis courts, and croquet lawns, as well as its river frontage.[7] The London County Council and Fulham Council considered calling the new open space "Hurlingham Playing Fields",[10] before deciding to retain the Hurlingham Park name.

The first section of the new public park – featuring a children's playground with swings, see-saw, a rocking boat, and a maze – was officially opened in October 1952.[11] The opening ceremony was attended by Edwin Bayliss, chairman of the London County Council; local MP Dr. Edith Summerskill; Fulham mayor Frank W. Banfield; and representatives from the Hurlingham Club.[11]

Sports facilities

The opening meeting of the track was on 11 September 1954. The running track was originally made of cinder.

A grandstand was built in 1936 to replace an earlier version but it was allowed to become run down in the 1990s and, in spite of strong local opposition, was demolished in 2002. It had a capacity of approximately 2,500 on bench type seating. The stadium has been replaced by a considerably smaller pavilion with no public facilities. The infield is a well maintained grass pitch and is used for either rugby union or football.

The track has a 200 metres (220 yards) straight on the home straight next to the grandstand which extends past the regular start line although the extension has been fenced off. The track was the base of London Athletic Club and the straight was last thought to be used for a race in 1979. A meeting was held with exactly the same schedule of events as the first open championship in 1879 and thus included a 220-yard straight race (200 metres).

In 2009, a three-day polo tournament was held in Hurlingham Park – the first time in 70 years that polo had been played there – with grandstands specially erected for the event.[12][3] Hundreds of primary school pupils from schools in Hammersmith and Fulham received polo lessons as part of their PE curriculum in 2010.[13]

Buildings

One of the oldest surviving buildings in Hurlingham Park is Field Cottage, a lodge which was rebuilt in 1856 in solid stone.[7] In the 1860s, Hurlingham Field Cottage was used as an orphanage and industrial home for girls, run by Elizabeth Palmer, a local benefactress.[7]

In popular culture

The Monty Python sketch "The 127th Upper Class Twit of the Year Competition from Hurlingham Park" was filmed there in 1969.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ "Yahoo". aolsearch.aol.co.uk.

- 1 2 3 Drake, Craig (13 May 2011). "Play Horse". City A.M. Retrieved 31 October 2023 – via EBSCOHost.

- 1 2 3 "MINT Polo is back in town". City AM. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2023 – via EBSCOHost.

- 1 2 Johnson, Kim Howard (1989). The First 200 Years of Monty Python. New York: St Martin's Press. pp. 47, 73. ISBN 0-312-03309-5.

- ↑ "Green Flag Award winners". Horticulture Week. August 2013. pp. 18–31. Retrieved 31 October 2023 – via EBSCOHost.

- ↑ "Exclusive ticket offer". Daily Telegraph. 24 April 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2023 – via EBSCOHost.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Denny, Barbara (1990). A History of Fulham. London: Historical Publications. pp. 50, 122. ISBN 9780948667077.

- ↑ "New Year Hopes". Fulham Chronicle. 2 January 1948. p. 8. Retrieved 1 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Don't store your skips in our beautiful park – residents tell council". The Gazette. Hammersmith, London. 5 June 1998. p. 16. Retrieved 1 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "'Hurlingham Park'?". Fulham Chronicle. 8 February 1952. p. 7. Retrieved 1 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Hurlingham Park will be a boon to all". Fulham Chronicle. 17 October 1952. p. 4. Retrieved 1 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Barney, Katahrine (28 October 2008). "Polo's coming home with new tournament at Hurlingham". Evening Standard. Retrieved 31 October 2023 – via EBSCOHost.

- ↑ Stewart, Tim (3 March 2010). "Free lessons in polo a hit with primary pupils". Evening Standard. Retrieved 31 October 2023 – via EBSCOHost.