| 1924 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 18, 1924 |

| Last system dissipated | November 24, 1924 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Cuba" |

| • Maximum winds | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 910 mbar (hPa; 26.87 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 5 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 179 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

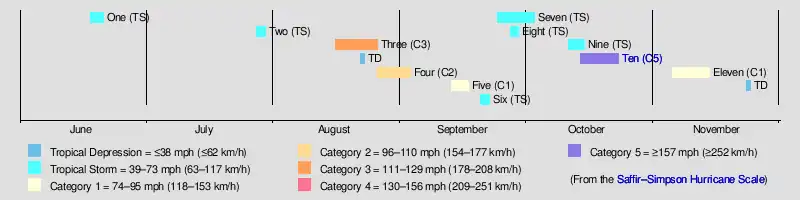

The 1924 Atlantic hurricane season featured the first officially recorded Category 5 hurricane, a tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds exceeding 155 mph (249 km/h) on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale. The first system, Tropical Storm One, was first detected in the northwestern Caribbean Sea on June 18. The final system, an unnumbered tropical depression, dissipated on November 24. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. Of the 13 tropical cyclones of the season, six existed simultaneously. The season was average with 11 tropical storms, five of which strengthened into hurricanes. Further, two of those five intensified into major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale.

The most significant storm of the season was Hurricane Ten, nicknamed the 1924 Cuba hurricane. It struck western Cuba as a Category 5 hurricane, before weakening and making landfall in Florida as a Category 1 hurricane. Severe damage and 90 fatalities were collectively reported at both locations. Another system, Hurricane Four, brought strong winds and flooding to the Leeward Islands. The storm left 59 deaths, 30 of which were on Montserrat alone. Several other tropical cyclones impacted land, including Tropical Storms One, Eight, and Ten, as well as Hurricanes Three and Five, and the remnants of Hurricane Three and Four. Overall, the storms of the 1924 Atlantic hurricane season collectively caused at least 179 fatalities.

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 100,[1] above the 1921–1930 average of 76.6.[2] ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[1]

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 18 – June 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); <1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm was detected 75 miles (121 km) southeast of Chetumal, Quintana Roo on June 18. It made landfall on northern Belize with estimated winds near 45 mph (72 km/h). Pressures were progressively decreasing over the preceding days in the northwestern Caribbean Sea.[3] The tropical system crossed the Yucatán Peninsula, emerging over the Bay of Campeche on June 19 with 40 mph (64 km/h) winds.[4] It re-strengthened over water and re-attained winds of 45 mph (72 km/h). Early on June 21, the storm made landfall 115 miles (185 km) south of Tampico, Tamaulipas. It dissipated over land. The cyclone was classified as a weak disturbance, and strong winds were not recorded throughout the life span of the storm. Squalls affected the Texas coast, prompting advisories for small watercraft. Heavy rainfall was reported in Mexico.[3]

Tropical Storm Two

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 28 – July 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); <999 mbar (hPa) |

Toward the end of July, a decaying cold front off the east coast of Florida resulted in the formation of a tropical storm, which possessed some hybrid cyclone characteristics. The storm tracked northeast, steadily intensifying to reach peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) as it passed near the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Later it weakened over colder sea surface temperatures. On July 30, it was absorbed by a cold front to the south of Nova Scotia.[4]

Hurricane Three

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 16 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 963 mbar (hPa) |

The third tropical cyclone of the season formed 420 miles (680 km) southeast of Bridgetown, Barbados on August 16. It moved northwest and crossed the eastern Caribbean as a minimal tropical storm on August 18. It passed east of San Juan, Puerto Rico and re-entered the Atlantic Ocean on August 9. It quickly strengthened, reaching hurricane status by the following day. The cyclone slowed and turned west on August 21, and it continued to strengthen east of the northern Bahamas. The cyclone strengthened to a peak intensity of 120 mph (190 km/h) north of Grand Bahama on August 24. At the time, the storm was nearly stationary. The cyclone turned sharply north, remaining offshore the East Coast of the United States. On August 25, it quickly weakened, and it passed close to Cape Hatteras on August 26. It transitioned to an extratropical cyclone, before passing over Nova Scotia on August 27.[4]

The approach of the storm led to the issuance of storm warnings from Miami, Florida, to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina on August 22. Hurricane warnings extended from Beaufort, North Carolina, to Cape Henry, Virginia. In advance of the storm, radio broadcasts also advised shipping interests to remain cautious north of Puerto Rico.[3] No damages occurred along the coast because of the recurving storm.[3] Peak wind gusts reached 74 mph (119 km/h) at Hatteras, North Carolina, and two people drowned along the coast.[5] Damage was minimal, though Ocracoke Island was flooded during the storm.[5] The White Star passenger liner Arabic was battered by the storm on August 26 while the ship was off the Nantucket Shoals. The ship arrived in New York the following day with 75 injured after having what was reported as a "100-foot wave" crash over the liner.[6] The remnants of the hurricane caused severe damage to electrical and telegraph lines and trees in Atlantic Canada, especially in Nova Scotia. Offshore, maritime incidents relating to the storm resulted in the drownings of 26 people after their schooners capsized.[7]

August tropical depression

On August 22, a strong tropical wave merged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa and quickly developed into a tropical depression later that day. A nearby ship recorded a sustained wind speed of 40 mph (64 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 1,009 mbar (29.8 inHg). However, because no other gale-force winds were observed, the depression was not upgraded to a tropical storm by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project in 2009. The depression moved northwestward through the Cape Verde Islands but likely dissipated on August 23.[8]

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); <965 mbar (hPa) |

The fourth tropical storm of the season developed 800 miles (1,300 km) southeast of Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe on August 25. Initially, it moved west on August 26. On August 27, it turned west-northwest and intensified as it approached the Lesser Antilles. It strengthened to a hurricane on August 28 and crossed Cudjoe Head on the island of Montserrat.[4] A minimum pressure of 965 mbar (28.5 inHg) was recorded. The cyclone turned northwest, crossing the northeastern Caribbean near Anguilla on August 29. The hurricane continued to intensify over the western Atlantic Ocean, and it reached peak winds of 105 mph (169 km/h) when it was located 755 miles (1,215 km) south-southeast of Bermuda on August 30.[4]

The cyclone recurved northward on September 2 and weakened to the equivalent of a Category 1 hurricane on September 3. The storm lost tropical characteristics on September 4, but retained hurricane-force winds when it struck Nova Scotia on September 5.[4] In the Virgin Islands, the cyclone destroyed hundreds of homes and severely damaged crops. Several deaths were reported. Heavy precipitation caused flooding on several islands in the path of the storm.[3] On Saint Thomas, small boats were wrecked and trees were uprooted by the winds.[9] More than 6,000 people were homeless on Montserrat, while 30 were dead and 200 received wounds. Damages were estimated near £100,000 on the island.[10] The Red Cross donated $3,000 and fed victims after the storm.[11] In total, damages reached £86,000 and at least 59 people were killed in the Leeward Islands.[10] Offshore Newfoundland, at least two people drowned and ten others were reported as missing after they abandoned their schooner.[12]

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 13 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

On September 12, a strong tropical storm developed 85 miles (137 km) southwest of Key West, Florida. It moved northwest, quickly strengthening to a hurricane on September 13. Shortly thereafter, the storm attained maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). Late on September 14, the cyclone turned northeast, and it struck the Florida Panhandle near Port St. Joe on September 15.[3] The hurricane quickly weakened to a tropical storm as it moved inland, crossing southern Georgia on September 16. It entered the Atlantic Ocean near Savannah, Georgia, with winds near 45 mph (72 km/h). The storm accelerated east-northeastward, becoming extratropical off Cape Hatteras on September 17. The system was last detected on September 19 south of Newfoundland.[4]

In Florida, minor damage to properties was reported. Wind gusts reached 75–80 mph (121–129 km/h) in Port St. Joe. Two fishing vessels were blown ashore in the area, while a schooner was wrecked near Carrabelle. Advance warnings reduced the potential damages in northwest Florida.[3] Heavy rains fell across the Florida panhandle, the Carolinas, and southeast Virginia, with the highest amount reported of 14.83 inches (377 mm) at Beaufort, North Carolina.[13] In Georgia, heavy precipitation caused two deaths and significant crop damage. Most of Brownton, Georgia was destroyed by floods.[14] Gale-force winds also occurred along the Eastern Seaboard, though warnings were released in advance of the winds.[3] Operationally, the cyclone was not believed to have attained hurricane intensity.[3] The hurricane was generally unexpected in the Tampa, Florida, area.[15] In Nova Scotia, the remnants of the cyclone dropped 2.7 inches (69 mm) of precipitation in Halifax, one of the heaviest rainfall episodes in that municipality in 1927.[16]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 20 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); ≤1005 mbar (hPa) |

On September 20, a weak tropical storm was observed over the islands of Cape Verde. It tracked slowly northwestward through the archipelago. Ship observations were sparse in tracking the storm; it was last observed on September 22.[4]

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – October 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); <1007 mbar (hPa) |

It is estimated a tropical depression formed south of the Cape Verde islands on September 24. It moved generally west-northwestward and slowly intensified. By September 28 it began recurving northward as winds increased to about 50 mph (80 km/h). The storm weakened and later re-intensified to the same peak intensity on October 2. It became extratropical on October 3, while turning northeastward. The remnants were absorbed by a larger extratropical storm on October 5.[4]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 27 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); ≤999 mbar (hPa) |

Low pressures were reported in the northwestern Caribbean Sea from September 23 through September 27.[3] On the latter day, a minimal tropical storm formed over the southwestern Caribbean Sea east of Roatán, Honduras. On September 28, the cyclone moved northward and slowly intensified, passing east of Cozumel. On September 29, it entered the southern Gulf of Mexico, attaining its maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) as a tropical system. It quickly accelerated northeast and transitioned to an extratropical system with 60 mph (97 km/h) winds.[4] Later, it entered the Big Bend of Florida near Cedar Key.[3] On September 30, it rapidly moved northeast across the coastal Southeastern United States. It was last detected near Norfolk, Virginia.[4] Storm warnings were released for the eastern Gulf Coast of the United States on September 29, advising residents to prepare for gale-force winds. Warnings were also issued from Jacksonville, Florida, to Fort Monroe, Virginia. Eventually, warnings also encompassed the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States. Gale-force winds affected the East Coast of the United States.[3]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 11 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); <1004 mbar (hPa) |

The pattern that led to the formation of this system led to a significant heavy rainfall event in eastern Florida, which experienced prolonged easterly flow within its northeastern periphery. Between October 4 and October 11, 36.45 inches (926 mm) fell at New Smyrna.[17] Early on October 12, the sixth tropical cyclone of the season developed in the eastern Gulf of Mexico 280 miles (450 km) southwest of Saint Petersburg, Florida. At the time, the storm was estimated to have attained its maximum intensity of 60 mph (97 km/h). It moved quickly southwest and weakened to a minimal tropical storm on October 13. The system weakened to a tropical depression on October 14 and dissipated over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico the following day.[4] Operationally, the system was classified as a moderate disturbance.[18]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 14 – October 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-min); 910 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Cuba Hurricane of 1924

Late on October 13, a minimal tropical storm formed in the western Caribbean Sea east-northeast of northern Honduras.[4] The storm moved slowly west-northwest and gradually turned north on October 15. Later that day, it steadily intensified, attaining hurricane intensity on October 17. It strengthened to the equivalent of a major hurricane on October 19. The storm then struck the Pinar del Río Province of Cuba with sustained winds of 165 mph (266 km/h). On October 20, the hurricane turned east-northeast in response to the southward movement of a ridge.[3] It quickly weakened and made landfall in Southwest Florida near Naples, Florida as a Category 1 hurricane.[19] The storm entered the Atlantic Ocean north of Miami with 70 mph (110 km/h) winds. The cyclone steadily weakened as it moved across the western Atlantic Ocean, before dissipating west-southwest of Bermuda on October 23.[4] Following reanalysis released in March 2009, the storm was re-classified as a Category 5 with winds of 165 mph (266 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 910 mbar (27 inHg).[20]

In Cuba, at least 90 people were killed.[21] The hurricane produced severe damage to crops and buildings across western Cuba, injuring 50–100 people in Arroyos de Mantua.[3][22] In Florida, watercraft were secured and trees were trimmed in anticipation of the storm.[23] Peak wind gusts reached 66 mph (106 km/h) in Key West, where damage to vegetation was minimal.[3] The hurricane produced heavy precipitation across southern Florida, peaking at 23.22 inches (590 mm) on Marco Island.[23] The rains caused flooding in Palm Beach County, disrupting traffic on highways and railroads. The measured totals of 11.21 inches (285 mm) were believed to have been the highest rainfall in the county over the past 15 years. Peak gusts reached 68 mph (109 km/h) across the mainland of southern Florida, while sailing trips from southeastern Florida were cancelled. Telegraph wires were disabled in Fort Myers and Punta Gorda, though damages were minimal.[24]

Hurricane Eleven

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 5 – November 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); <994 mbar (hPa) |

Early on November 5, a tropical storm formed in the southern Caribbean Sea, while located about 275 miles (443 km) north-northwest of Panama City, Panama.[4] The system moved northward with winds of minimal intensity, and it struck Clarendon Parish, Jamaica on November 7 with 40 mph (64 km/h) sustained winds. Early on November 8, it left the northern coast of the island, and it strengthened prior to making landfall west of Santiago de Cuba on November 9.[4] Later, the cyclone strengthened to a hurricane as it entered the Atlantic Ocean, and it turned northeast over the Turks and Caicos Islands on November 10.[3] The hurricane accelerated while heading away from the Turks and Caicos Islands on November 11. Shortly thereafter, it attained a peak intensity of 80 mph (130 km/h) and maintained Category 1 status until November 13. The system passed east of Bermuda and weakened to a tropical storm on November 14. It quickly became extratropical and was last reported on November 15.[3][4]

November tropical depression

Historic weather maps and observations from ships indicate that a tropical depression formed in the southwestern Caribbean on November 23. The depression tracked westward and organized further, though the highest sustained wind speed observed in relation to the system was 29 mph (47 km/h) By November 24, the depression dissipated.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ↑ Christopher W. Landsea; et al. (February 1, 2012). "A Reanalysis of the 1921–30 Atlantic Hurricane Database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 (3): 869. Bibcode:2012JCli...25..865L. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00026.1. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Monthly Weather Review (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1924. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 James E. Hudgins (April 2000). Tropical Cyclones Affecting North Carolina since 1566 – An Historical Perspective (Report). Blacksburg, Virginia National Weather Service. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ "Gale-lashed Arabic docks with 75 hurt; 4 other liners hit". The New York Times. August 28, 1924. p. 1.

- ↑ 1924-2 (Report). Environment Canada. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- 1 2 Christopher W. Landsea; et al. "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ↑ "New Storm Hard on Heels of its Predecessor". The Daily Gleaner. 1924.

- 1 2 "Fund Opened to Aid Sufferers by Hurricane". The Daily Gleaner. 1924.

- ↑ "Red Cross Feeds Homeless Victims After Hurricane". The Bridgeport Telegram. September 4, 1924. p. 18. Retrieved August 27, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ 1924-3 (Report). Environment Canada. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ↑ United States Army Corps of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 3–16.

- ↑ "Hurricane Hits Georgia Towns". The Chronicle-Telegram. 1924.

- ↑ Robert W. Burpee (December 1989). "Gordon E. Dunn: Preeminent Forecaster of Midlatitude Storms and Tropical Cyclones". Weather and Forecasting. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. 4 (4): 573–584. Bibcode:1989WtFor...4..573B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1989)004<0573:GEDPFO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ↑ 1924-4 (Report). Environment Canada. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ↑ United States Army Corps of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 4–20.

- ↑ "Short Stories". The Port Arthur News. 1924.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake; Edward N. Rappaport; Christopher W. Landsea (2006). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones (1851 to 2006) (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ↑ Re-Analysis Project; March 2009. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Cuba Hurricanes Historic Threats". CubaHurricanes.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ "12 Killed, 100 Hurt in Hurricane in Florida". Oakland Tribune. Associated Press. October 22, 1924. p. 32. Retrieved August 27, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Barnes, Jay (1998). Florida's Hurricane History. Page 108.

- ↑ "Gulf Tornado Takes 13 Lives-50 are Injured". The San Antonio Express. Associated Press. 1924.