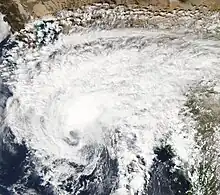

Hurricane Paul at peak intensity, after rapid deepening on October 15 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 13, 2012 |

| Remnant low | October 17, 2012 |

| Dissipated | October 18, 2012 |

| Category 3 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 959 mbar (hPa); 28.32 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | None reported |

| Damage | $15.6 million (2012 USD) |

| Areas affected | Baja California Peninsula, Northwestern Mexico |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2012 Pacific hurricane season | |

Hurricane Paul was a strong tropical cyclone that threatened the Baja California peninsula during October 2012. The sixteenth tropical cyclone, tenth hurricane, and fifth major hurricane of the season, Paul originated from a trough of low pressure west of the coastline of Mexico on October 13. While turning towards the north, the system quickly organized, reaching hurricane status in the morning of October 15. By that afternoon, Paul had reached its peak intensity as a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS) with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h), but began to weaken rapidly thereafter due to land interaction and strong wind shear. Late on October 17, Paul degenerated into a remnant low. The remnants of Paul later moved ashore along the central Baja California Peninsula, before dissipating on October 18.

Prior to the storm's arrival in Baja California Sur, hurricane watches and warnings were issued for coastal locations. Hundreds of homes were damaged across the region and damage to infrastructure was significant. Power outages also occurred across the region as a result of Hurricane Paul. A total of 400 homes were destroyed, and 300 others were flooded. Damage totaled $15.6 million (2012 USD).

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On September 28, a tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa. Tracking westward, the northern portion of this wave axis led to the formation of Tropical Storm Oscar on October 3 while the southern portion of the wave continued across the central Atlantic. While approaching the Lesser Antilles the following day, the disturbance lost most of its thunderstorm activity and remained poorly organized across the remainder of its trek through the Caribbean Sea and Central America. On October 10, the wave emerged into the East Pacific basin, at which time the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring the system.[1][2]

Characterized with disorganized convection, a broad surface trough formed in association with the wave the same day and environmental conditions were expected to favor gradual development.[3] Initially, upper-level winds were only marginally favorable, and although the thunderstorms remained disorganized, the NHC estimated a 50% chance for development by early on October 12.[4] The next day, the system became better defined,[5] and, the NHC noted that the system was on the verge of becoming a tropical cyclone.[6] Although operationally not classified until 21:00 UTC on October 13, a post-season analysis conducted on the system revealed that it attained enough organization to be considered a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC, while positioned about 645 mi (1040 km) south-southwest of Cabo San Lucas.[2]

Tracking westward around the southern periphery of a subtropical ridge,[7] the depression steadily strengthened, intensifying into Tropical Storm Paul six hours after designation. On October 14, an upper-level low positioned west of the Baja California peninsula led to a break in the ridge which subsequently caused the tropical cyclone to slow and turn northward. During this change in direction, favorable atmospheric conditions allowed for a quick rate of intensification.[2] Convective bands in association with Paul gained curvature and a central dense overcast feature became visible on satellite imagery.[8] In addition, a series of microwave passes late in evening revealed a nearly closed eyewall.[9] At 06:00 UTC on October 15, Paul was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane on the SSHWS while located approximately 595 mi (960 km) southwest of Cabo San Lucas. Banding features continued to become better defined to the south and east of the center while convection in the eyewall cooled to −85 °C (−121 °F).[10] The cloud pattern became increasingly symmetrical,[11] and an eye became intermittently visible on satellite imagery later that morning.[12] Following an abrupt increase in satellite intensity estimates, Paul was upgraded to a Category 3 major hurricane on the SSHWS, the fifth of the season, at 18:00 UTC on October 15.[2] Simultaneously, the hurricane also estimated to have attained its peak intensity of 120 miles per hour (195 km/h).[13]

Upon reaching its peak intensity, the hurricane began to steadily weaken. The cold ring of thunderstorm activity surrounding the eye warmed significantly, while the eye became cloud-filled and cool.[14] The circulation became tilted north-northeast with height, likely a byproduct of south-southwesterly wind shear,[15] and the system was downgraded to a Category 2 hurricane at 12:00 UTC on October 16. Accelerating northwestward within deep southwesterly flow, continued unfavorable upper-level winds caused the low-level center to rapidly separate from the convective mass.[16] At 18:00 UTC, Paul was downgraded to a Category 1 hurricane; by this time, little deep thunderstorm activity remained near the center. Six hours later, the system was downgraded to a tropical storm while it passed 50 mi (80 km) west of Baja California Sur. The remainder of shower and thunderstorm activity dissipated early on October 17 and Paul was declared a post-tropical cyclone at 06:00 UTC. Following declassification, the system moved ashore Baja California Sur near Bahía Asunción while maintaining gale-force winds. On the next day, at 06:00 UTC, the remnant low-level circulation dissipated about 70 mi (110 km) northwest of Punta Eugenia, Mexico.[2]

Preparations

When the system first posed a threat to Mexico at 09:00 UTC on October 15, a tropical storm watch was posted for a portion of the central Baja California Peninsula. Six hours later, the watch was upgraded into a tropical storm warning, while tropical storm watches were issued to the north and south of the warning, respectively. At 21:00 UTC on October 15, the tropical storm warnings was upgraded into a hurricane warning, while a tropical storm warning was declared along the eastern side of the peninsula. Early the next day, the tropical storm warning was extended southward, to include the capital of La Paz. On the afternoon of October 16, when the threat to the area increased, a hurricane warnings was posted for the eastern side of the state. Early the next day, all hurricane warnings were dropped, as Paul had deteriorated into a tropical storm. By 15:00 UTC, all watches and warnings had been discontinued.[2]

Prior to the arrival of Paul, activities were suspended for small craft in the ports of Cabo San Lucas, La Paz, San Carlos, Maria Magdalena, and Puerto Lopez Mateos.[17] Moreover, all activities were closed in the port of Mazatlan.[18] Twelve municipalities in Sonora were placed under a "green" alert,[19] though this was quickly upgraded to a "yellow" alert,[20] and later into an "orange" alert.[21] A "blue" alert also declared for Colima, Jalisco, and Nayarit.[17]

On October 16, a "yellow" alert (moderate risk) was activated for Baja California Sur.[22] State civil protection authorities brought teams from the federal electricity and water commissions to help maintain services during the storm. In addition, the state government opened 143 shelters,[23] including 11 in the towns of Cabo San Lucas, La Paz, Ciudad Constitución, and Loreto,[24] which had a capacity of 30,617 persons. Furthermore, 125 cranes and 75 automobiles were mobilized.[25] Statewide, 400 soldiers were deployed.[24] Roughly 500 residents in Comondú were evacuated to shelter.[26]

Impact and aftermath

During its formative stages, Paul passed near Clarion Island, where winds of 58 mph (93 km/h) and gusts of 77 mph (124 km/h) were recorded. On nearby Socorro Island, 1.98 in (50 mm) of rain fell during the storm's passage.[2]

Even though there were no reports of hurricane-force winds onshore the Baja California Peninsula (the storm weakened to a tropical storm when it made its closet approach to the region), hurricane-force winds did approach the peninsula, and there were widespread reports of gale-force winds. In Puerto Cortes, peak winds of 51 mph (82 km/h) and gusts up to 72 mph (116 km/h) were observed, as well as a peak rainfall total over 6.02 in (153 mm). Furthermore, a minimum barometric pressure of 973.4 mbar (28.74 inHg) was observed in Cabo San Lucas.[2]

The outer rainbands of the system first brought rains to Baja California Sur on October 15, resulting in flooding.[27] Around 30% of Baja California Sur residents were without power at the height of Paul.[2] Across the northern portion of the state, numerous roads were destroyed,[28] especially near Loreto, where flooding caused a 45 ft (14 m) sinkhole to form.[29] In addition, Mexican Federal Highway 11 was damaged in five locations from La Paz to Ciudad Constitucion.[30] In Loreto, significant destruction occurred and many residents were rendered homeless. Two creeks overflowed their banks, destroying several homes.[31] In Mulege, 300 homes were inundated, displacing 60 individuals to shelter. Thirty light poles were downed.[29] The Puerto San Carlos area sustained the worst flooding from the storm,[28] due to a combination of nearly a year's worth of rainfall and storm surge, which toppled a dike. There, about 400 homes collapsed and around 40% of the town's houses received damage, forcing 300 people to seek shelter. In San Ignacio, 30 automobiles were swept away and power was lost to the city.[29]

Across the city of La Paz, damage to roads was estimated at MX$200 million (US$15.6 million).[32][nb 1] In all, approximately 1,000 dwellings were damaged in relation to Hurricane Paul;[33] many other homes across the region were left without electricity and running water.[32] A total of 495 people were taken to shelters, including 93 in Ciudad Insurgentes and 300 in San Carlos.[30] Overall, 5,000 families or 16,000 people were directly affected by the hurricane.[34]

Elsewhere, in Sonora light rain was recorded.[33] In the aftermath of the storm, the Mexican navy activated a plan to provide aid. A total of 130 troops toured the damaged areas via six vehicles.[26] A state of emergency was declared for four municipalities in Baja California Sur.[35] By October 18, 95% of all water, power, and road services had been restored.[36] Roughly MX$2 million ($156,000 2012 USD) was spent to help rebuild businesses lost due to the storm.[37]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Michael J. Brennan (October 10, 2012). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Robbie J. Berg (January 4, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Paul (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Michael J. Brennan (October 10, 2012). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Todd Kimberlain (October 12, 2012). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ John Cangialosi (October 13, 2012). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (October 13, 2012). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ John Cangialosi (October 13, 2012). Tropical Storm Paul Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (October 14, 2012). Tropical Storm Paul Discussion Number 5. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Robbie J. Berg (October 14, 2012). Tropical Storm Paul Discussion Number 6. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi; Stacy R. Stewart (October 15, 2012). Hurricane Paul Discussion Number 7. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Todd Kimberlain; Daniel Brown (October 15, 2012). Hurricane Paul Discussion Number 8 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ Todd B. Kimberlain (October 14, 2012). Hurricane Paul Discussion Number 9. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 4, 2023). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2022". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Robbie J. Berg; Richard J. Pasch (October 16, 2012). Hurricane Paul Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi; Stacy R. Stewart (October 16, 2012). Hurricane Paul Discussion Number 11. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 16, 2012). Hurricane Paul Discussion Number 14. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- 1 2 Gladys Rodriguez (October 15, 2012). "BCS closes ports in 3 municipalities". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ↑ Gladys Rodriguez (October 15, 2012). "Mazatlan closed by Hurricane Paul Recommend caution in costs and states of Baja California and northwestern". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Alerta amarilla en Sonora por "Paul"". El Universal (in Spanish). October 16, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Sonora decreta alerta verde por huracán Paul". El Universal (in Spanish). October 16, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Sonora acitvada alerta naranja de Paul". El Universal (in Spanish). October 16, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "BCS acuerda instalación de albergues ante Paul". El Universal (in Spanish). October 16, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ Ignacio Martinez (August 16, 2014). "Hurricane Paul races toward Baja peninsula, causing flooding, stranding some drivers". Associated Press.

- 1 2 "Ejército aplica plan DN-3 en BCS por Paul". El Universal (in Spanish). October 16, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Evacuan a familias por cercanía de Paul en BCS". El Universal (in Spanish). October 16, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- 1 2 "Paul pega a Baja California; desalojan a 500 pobladores". El Universal (in Spanish). October 17, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ Gladys Rodriguez (October 15, 2012). "BCS monitored rivers to the presence of Hurricane Paul". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- 1 2 "Paul deja inundaciones en Baja California Sur". El Universal (in Spanish). October 17, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Paul dejó mil viviendas afectadas en BCS". El Universal (in Spanish). October 17, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- 1 2 "Paul sólo provocó daños en 2 municipios". El Sud Californiano (in Spanish). October 17, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ Raúl Villalobos Davis (October 18, 2012). "Evalúan daños del huracán "Paul"". El Sud Californiano (in Spanish). Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- 1 2 Haydee Ramirez (October 2012). "Paul damage report" (in Spanish). Terra Mexico. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- 1 2 "Inundaciones de Paul dejan daños en mil viviendas en BC". El Universal (in Spanish). October 16, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "BCS reporta 16 mil afectados tras paso de Paul". El Universal (in Spanish). October 19, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Declaran emergencia para cuatro municipios de BCS". El Universal (in Spanish). October 17, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "BCS restablece 95% de servicios tras paso de 'Paul'". El Universal (in Spanish). October 18, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ Raúl Villalobos Davis (January 23, 2013). "Entregarán apoyos por daños ocasionados por "Paul"". El Sud Californiano (in Spanish). Retrieved June 16, 2014.

External links

- The NHC's advisory archive on Hurricane Paul