| Hypnosis |

|---|

Hypnotic induction is the process undertaken by a hypnotist to establish the state or conditions required for hypnosis to occur.

Self-hypnosis is also possible, in which a subject listens to a recorded induction or plays the roles of both hypnotist and subject.[2]

Traditional techniques

James Braid in the nineteenth century saw fixing the eyes on a bright object as the key to hypnotic induction.[3]

A century later, Sigmund Freud saw fixing the eyes, or listening to a monotonous sound as indirect methods of induction, as opposed to “the direct methods of influence by way of staring or stroking”[4]—all leading however to the same result, the subject's unconscious concentration on the hypnotist. The swinging watch and intense eye gaze -- staples of hypnotic induction in film and television -- are not used in practice as the rapidly changing movements, and the obvious cliché of their application, would be distracting rather than focusing.

Debates

Hypnotic induction may be defined as whatever is necessary to get a person into the state of trance[5] — i.e., when understood as a state of increased suggestibility, during which critical faculties are reduced, and subjects are more prone to accept the hypnotist's commands and suggestions.[6] Evidence of changes in brain activity and mental processes have also been associated experimentally with hypnotic inductions.[7]

Theodore X. Barber argued that techniques of hypnotic induction were merely empty-but-popularly-expected rituals, inessential for hypnosis to occur: hypnosis on this view is a process of influence, which is only enhanced (or formalized) through expected cultural rituals.[8]

Oliver Zangwill pointed out in opposition that, while cultural expectations are important in hypnotic induction, seeing hypnosis only as a conscious process of influence fails to account for such phenomena as posthypnotic amnesia or post-hypnotic suggestion.[9]

Faster methods of hypnotic induction

In early hypnotic literature a hypnosis induction was a gradual, drawn-out process. Methods were designed to relax the hypnotic subject into a state of inner focus (during which their imagination would come to the forefront) and the hypnotist would be better able to influence them and help them effect changes at the subconscious level.[10]

These are still used, notably in hypnotherapy, where the gradual relaxation of a client may be preferred over faster inductions. Generally, a hypnotherapist will use the induction they find most appropriate and effective for each individual client.

However, newer and faster methods have been suggested -- such as the Elman Induction, introduced by Dave Elman[11] -- which involve having the subject imagine that their eyes are too relaxed to open, so that the harder that they try to open them, the harder it becomes to open them (otherwise known as a double-bind). The therapist then raises the subject's arm and allows it to drop, to further impress the state of relaxation. Lastly, the therapist has the subject visualize clouds and numbers within those clouds, as they blow away (each number that blows away increases the effect of the trance) until the subject is too tired to think of any more numbers. This process takes several minutes, but has been known to be effective enough to prepare patients for certain types of surgery.

However, there are even faster instant hypnosis inductions (such as 'snap' inductions) which employ the principles of shock and surprise. A shock to the nervous system of the subject causes their conscious mind to be temporarily disengaged. During this brief window of distraction the hypnotist quickly intervenes, allowing the subject to enter the state of intense, hyper imagination and inner focus.[12]

Literary examples

- In George du Maurier's Trilby, we are told of the hypnotist Svengali that “with one look of his eye – with a word – Svengali could turn her into the other Trilby”.[13]

See also

Notes

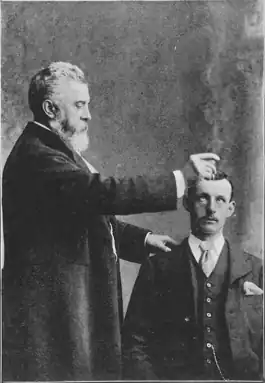

- ↑ Coates (1904), Figure II, facing p.23.

- ↑ Baryss, Imants (2003). Alterations of Consciousness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. p. 109.

- ↑ O. L. Zangwill, 'History of Hypnotism' in R. Gregory ed., The Oxford Companion to the Mind (1987) p. 331; also Yeates (2013).

- ↑ S. Freud, Civilization, Society and Religion (PFL 12) p. 158-9

- ↑ Baryss, Imants (2003). Alterations of Consciousness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. p. 110.

- ↑ Keys To The Mind - How to Hypnotize Anybody and Practice Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy Correctly - by Dr. Richard K Nongard and Nathan Thomas

- ↑ M. R. Nash ed., Oxford Handbook of Hypnotism (2011) p. 387

- ↑ O. L. Zangwill, 'Experimental Hypnosis' in R. Gregory ed., The Oxford Companion to the Mind (1987) p. 330

- ↑ O. L. Zangwill, 'Experimental Hypnosis' in R. Gregory ed., The Oxford Companion to the Mind (1987) p. 330

- ↑ Time Distortion – A Comparison of Hypnotic Induction and Progressive Relaxation Procedures: A Brief Communication - Clement von Kirchenheim & Michael A. Persinger

- ↑ A. Jain, Clinical and Meditative Hypnotherapy (2006) p. 10

- ↑ See, for instance, Gil Boyne's Transforming Therapy a New Approach to Hypnotherapy (1989) ISBN 978-0-930-29813-5, and Charles Tebbetts' Miracles on Demand (1987), ISBN 0930298284

- ↑ Du Maurier, quoted in J. Pintar/S. J. Lynn, Hypnosis: A Brief History (2009) p. 1

References

Further reading

- T. X. Barber, Hypnosis (1969)

- A. Barabasz/J. G. Watkins, Hypnotherapeutic Techniques (2005)

- Yeates, L.B., James Braid: Surgeon, Gentleman Scientist, and Hypnotist, Ph.D. Dissertation, School of History and Philosophy of Science, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, January 2013.