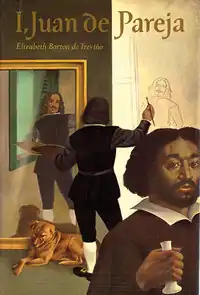

First edition | |

| Author | Elizabeth Borton de Treviño |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's novel |

| Publisher | Farrar, Straus and Giroux |

Publication date | June 1965 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 192 |

I, Juan de Pareja is a novel by American writer Elizabeth Borton de Treviño, which won the Newbery Medal for excellence in American children's literature in 1966.

The book is based on the Portrait of Juan de Pareja, the real-life portrait that Diego Velázquez made of his slave Juan de Pareja. It is written in the first person as by the title character de Pareja, a half-African slave of Velázquez's.

Plot

Juan de Pareja is born into slavery in Seville, Spain in the early 1600s, and after the death of his mother when he is just five years old he becomes the pageboy of a wealthy Spanish lady, Emilia. At the end of the first chapter, both Doña Emilia and Juan's master die. Brother Isidro saves Juan from death and brings him to a group of people. They hand him off to a man named Don Carmelo to deliver him to Emilia's nephew, Don Diego Velázquez.

Diego has a wife, Juana de Miranda, and two little girls, Paquita and Ignacia. Juan's main job is to help his master with his work of painting: grinding the pigments, placing the paints on the palette, washing the brushes, and making the canvas frames. Although he is regularly present when Diego paints, Juan is not allowed to paint as he is a slave and the Spanish laws forbid it.

Two students, Cristobal and Alvaro, join the household as Diego's apprentices. Juan dislikes Cristobal, whose opinions do not differ from his master and his family's, but finds Alvaro pleasant enough. Diego is invited to paint the king's portrait. He and his family and Juan and the apprentices move to the living quarters on the palace grounds. When an artist named Peter Paul Rubens visits, Juan falls in love with a slave girl named Miri. Juan accompanies Diego to Italy, where he begins to purchase art supplies to try painting and drawing on his own while keeping it a secret from the Velázquezes. Paquita falls in love with an apprentice named Juan Bautista del Mazo and they marry.

During a hunting expedition, Juan saves the king's hound by treating him with herbal medicine. Juan gets to know the king's court entertainers, many of whom are dwarves. When Bartolomé Esteban Murillo of Seville becomes Diego's apprentice, he treats Juan as a friend. During their visits to Church, when Juan declines the Eucharist, Murillo asks what is the matter, and Juan replies he has been feeling guilty about breaking the law and master's trust by painting. Murillo does not believe painting to be a sin, but recommends Juan confess to a priest about stealing their master's paints, and that he should wait for an appropriate time to tell his master that he has been painting.

On Diego and Juan's second visit to Italy, Diego falls ill from seasickness and his hand becomes unsteady; he wonders if he can paint anymore. Juan prays for him to get well. When Diego is asked to paint a portrait of Pope Innocent X, he paints Juan as practice, and Juan uses the portrait to acquire commissions from other Italian noblemen. Returning to Spain, Juan meets Juana de Miranda's a new slave named Lolis, whom he finds attractive.

In one of the routine visits by the king, Juan eventually reveals that he has been painting, but Diego writes a note that makes Juan a free man and his Assistant. Juan asks for Lolis' hand in marriage, which prompts Juana to write a similar note freeing Lolis. Paquita dies giving birth to her stillborn second child, while Juana dies from an illness two months later. Diego paints portraits and settings for the wedding by proxy of the king's sister Infanta Maria Teresa to King Louis XIV of France. Diego falls ill, and despite recovering briefly, he dies; the king has Juan help him paint a cross on Diego's self-portrait in Las Meninas, posthumously bestowing him the Order of Santiago honor. Juan and Lolis return to Seville, where he takes up studio residence with Murillo and their family.

Reception

In addition to winning the Newbery Medal, the novel received positive reception from the School Library Journal, The Horn Book Magazine, The New York Times, and other outlets.[1] In a retrospective essay about the Newbery Medal-winning books from 1966 to 1975, children's author John Rowe Townsend wrote, "One might suspect that the book reflects in part a well-meant, but no longer acceptable, view of a black man as being a white man under the skin; for whom the brightest prospect is that of raising himself into acceptance by his former superiors."[2]

References

- ↑ "MacMillan". Archived from the original on 2013-10-13. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- ↑ Townsend, John Rowe (1975). "A Decade of Newbery Books in Perspective". In Kingman, Lee (ed.). Newbery and Caldecott Medal Books: 1966-1975. Boston: The Horn Book, Incorporated. p. 143. ISBN 0-87675-003-X.