| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 388,900[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 101,795[3] | |

| 42,716[4] | |

| 9,308[5] | |

| 8,274[6] | |

| 5,454[6] | |

| 2,225[6] | |

| 1,802[6] | |

| 1,500[7] | |

| 1,122[6] | |

| 1,046[6] | |

| 980[8] | |

| 492[6] | |

| 223[9] | |

| Other countries combined | c. 3,000[6] |

| Languages | |

| Icelandic | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheranism (mainly the Church of Iceland);[10] Neo-pagan; Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox minorities among other faiths; secular. Historically Norse paganism, and Catholicism (c. 1000 – 1551). See Religion in Iceland | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Norwegians, Danes, Swedes, Faroe Islanders, Irish, Scottish | |

a Icelandic citizens | |

Icelanders (Icelandic: Íslendingar) are an ethnic group and nation who are native to the island country of Iceland. They speak Icelandic, a North Germanic language.

Icelanders established the country of Iceland in mid 930 CE when the Alþingi (parliament) met for the first time. Iceland came under the reign of Norwegian, Swedish and Danish kings but regained full sovereignty from the Danish monarchy on 1 December 1918, when the Kingdom of Iceland was established. On 17 June 1944, Iceland became a republic. Lutheranism is the predominant religion. Historical and DNA records indicate that around 60 to 80 percent of the male settlers were of Norse origin (primarily from Western Norway) and a similar percentage of the women were of Gaelic stock from Ireland and peripheral Scotland.[11][12]

History

Iceland is a geologically young land mass, having formed an estimated 20 million years ago due to volcanic eruptions on the Mid-Atlantic ridge. One of the last larger islands to remain uninhabited, the first human settlement date is generally accepted to be 874, although there is some evidence to suggest human activity prior to the Norse arrival.[13]

Initial migration and settlement

The first Viking to sight Iceland was Gardar Svavarsson, who went off course due to harsh conditions when sailing from Norway to the Faroe Islands. His reports led to the first efforts to settle the island. Flóki Vilgerðarson (b. 9th century) was the first Norseman to sail to Iceland intentionally. His story is documented in the Landnámabók manuscript, and he is said to have named the island Ísland (Iceland). The first permanent settler in Iceland is usually considered to have been a Norwegian chieftain named Ingólfur Arnarson. He settled with his family in around 874, at a place he named "Bay of Smokes", or Reykjavík in Icelandic.[14]

Following Ingólfur, and also in 874, another group of Norwegians set sail across the North Atlantic Ocean with their families, livestock, slaves, and possessions, escaping the domination of the first King of Norway, Harald Fairhair. They traveled 1,000 km (620 mi) in their Viking longships to the island of Iceland. These people were primarily of Norwegian, Irish or Gaelic Scottish origin. The Irish and the Scottish Gaels were either slaves or servants of the Norse chiefs, according to the Icelandic sagas, or descendants of a "group of Norsemen who had settled in Scotland and Ireland and intermarried with Gaelic-speaking people".[15] Genetic evidence suggests that approximately 62% of the Icelandic maternal gene pool is derived from Ireland and Scotland, which is much higher than other Scandinavian countries, although comparable to the Faroese, while 37% is of Nordic origin.[16] About 20–25% of the Icelandic paternal gene pool is of Gaelic origin, with the rest being Nordic.[17]

The Icelandic Age of Settlement (Icelandic: Landnámsöld) is considered to have lasted from 874 to 930, at which point most of the island had been claimed and the Alþingi (Althing), the assembly of the Icelandic Commonwealth, was founded at Þingvellir.[18]

Hardship and conflict

In 930, on the Þingvellir (English: Thingvellir) plain near Reykjavík, the chieftains and their families met and established the Alþingi, Iceland's first national assembly. However, the Alþingi lacked the power to enforce the laws it made. In 1262, struggles between rival chieftains left Iceland so divided that King Haakon IV of Norway was asked to step in as a final arbitrator for all disputes, as part of the Old Covenant. This is known as the Age of the Sturlungs.[19]

Iceland was under Norwegian leadership until 1380, when the Royal House of Norway died out. At this point, both Iceland and Norway came under the control of the Danish Crown. With the introduction of absolute monarchy in Denmark, the Icelanders relinquished their autonomy to the crown, including the right to initiate and consent to legislation. This meant a loss of independence for Iceland, which led to nearly 300 years of decline: perhaps largely because Denmark and its Crown did not consider Iceland to be a colony to be supported and assisted. In particular, the lack of help in defense led to constant raids by marauding pirates along the Icelandic coasts.[20]

Unlike Norway, Denmark did not need Iceland's fish and homespun wool. This created a dramatic deficit in Iceland's trade, and no new ships were built as a result. In 1602, Iceland was forbidden to trade with other countries by order of the Danish Government, and in the 18th century climatic conditions had reached an all-time low since Settlement.[20]

In 1783–84, Laki, a volcanic fissure in the south of the island, erupted. The eruption produced about 15 km3 (3.6 cu mi) of basalt lava, and the total volume of tephra emitted was 0.91 km3.[21] The aerosols that built up caused a cooling effect in the Northern Hemisphere. The consequences for Iceland were catastrophic, with approximately 25–33% of the population dying in the famine of 1783 and 1784. Around 80% of sheep, 50% of cattle, and 50% of horses died of fluorosis from the 8 million tons of fluorine that were released.[22] This disaster is known as the Mist Hardship (Icelandic: Móðuharðindin).

In 1798–99, the Alþingi was discontinued for several decades, eventually being restored in 1844. It was moved to Reykjavík, the capital, after being held at Þingvellir for over nine centuries.

Independence and prosperity

The 19th century brought significant improvement in the Icelanders' situation. A protest movement was led by Jón Sigurðsson, a statesman, historian, and authority on Icelandic literature. Inspired by the romantic and nationalist currents from mainland Europe, Jón protested strongly, through political journals and self-publications, for 'a return to national consciousness' and for political and social changes to be made to help speed up Iceland's development.[23]

In 1854, the Danish government relaxed the trade ban that had been imposed in 1602, and Iceland gradually began to rejoin Western Europe economically and socially. With this return of contact with other peoples came a reawakening of Iceland's arts, especially its literature. Twenty years later in 1874, Iceland was granted a constitution. Icelanders today recognize Jón's efforts as largely responsible for their economic and social resurgence.[23]

Iceland gained full sovereignty and independence from Denmark in 1918 after World War I. It became the Kingdom of Iceland. The King of Denmark also served as the King of Iceland but Iceland retained only formal ties with the Danish Crown. On 17 June 1944 the monarchy was abolished and a republic was established on Jón Sigurðsson's 133rd birthday. This ended nearly six centuries of ties with Denmark.[23]

Demographics and society

Genetics

Due to their small founding population and history of relative isolation, Icelanders have often been considered highly genetically homogeneous as compared to other European populations. For this reason, along with the extensive genealogical records for much of the population that reach back to the settlement of Iceland, Icelanders have been the focus of considerable genomics research by both biotechnology companies and academic and medical researchers.[24][25] It was, for example, possible for researchers to reconstruct much of the maternal genome of Iceland's first known black inhabitant, Hans Jonatan, from the DNA of his present-day descendants partly because the distinctively African parts of his genome were unique in Iceland until very recent times.[26]

Genetic evidence shows that most DNA lineages found among Icelanders today can be traced to the settlement of Iceland, indicating that there has been relatively little immigration since. This evidence shows that the founder population of Iceland came from Ireland, Scotland, and Scandinavia: studies of mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosomes indicate that 62% of Icelanders' matrilineal ancestry derives from Scotland and Ireland (with most of the rest being from Scandinavia), while 75% of their patrilineal ancestry derives from Scandinavia (with most of the rest being from the Irish and British Isles).[27]

Other studies have identified other ancestries, however. One study of mitochondrial DNA, blood groups, and isozymes revealed a more variable population than expected, comparable to the diversity of some other Europeans.[28] Another study showed that a tiny proportion of samples of contemporary Icelanders carry a more distant lineage, which belongs to the haplogroup C1e, which can possibly be traced to the settlement of the Americas around 14,000 years ago. This hints a small proportion of Icelanders have some Native American ancestry arising from Norse colonization of Greenland and North America.[29]

Icelanders also have an anomalously high Denisovan genetic heritage.[30]

Despite Iceland's historical isolation, the genetic makeup of Icelanders today is still quite different from the founding population, due to founder effects and genetic drift.[31] One study found that the mean Norse ancestry among Iceland's settlers was 56%, whereas in the current population the figure was 70%. This indicates that Icelanders with increased levels of Norse ancestry had higher reproductive success.[32]

Emigration

Greenland

The first Europeans to emigrate to and settle in Greenland were Icelanders who did so under the leadership of Erik the Red in the late 10th century and numbered around 500 people. Isolated fjords in this harsh land offered sufficient grazing to support cattle and sheep, though the climate was too cold for cereal crops. Royal trade ships from Norway occasionally went to Greenland to trade for walrus tusks and falcons. The population eventually reached a high point of perhaps 3,000 in two communities and developed independent institutions before fading away during the 15th century.[33] A papal legation was sent there as late as 1492, the year Columbus attempted to find a shorter spice route to Asia but instead encountered the Americas.

North America

According to the Saga of Eric the Red, Icelandic immigration to North America dates back to Vinland c. 1006. The colony was believed to be short-lived and abandoned by the 1020s.[34] European settlement of the region was not archeologically and historically confirmed as more than legend until the 1960s. The former Norse site, now known as L'Anse aux Meadows, pre-dated the arrival of Columbus in the Americas by almost 500 years.

A more recent instance of Icelandic emigration to North America occurred in 1855, when a small group settled in Spanish Fork, Utah.[35] Another Icelandic colony formed in Washington Island, Wisconsin.[36] Immigration to the United States and Canada began in earnest in the 1870s, with most migrants initially settling in the Great Lakes area. These settlers were fleeing famine and overcrowding on Iceland.[37] Today, there are sizable communities of Icelandic descent in both the United States and Canada. Gimli, in Manitoba, Canada, is home to the largest population of Icelanders outside of the main island of Iceland.[38]

Immigration

From the mid-1990s, Iceland experienced rising immigration. By 2017 the population of first-generation immigrants (defined as people born abroad with both parents foreign-born and all grandparents foreign-born) stood at 35,997 (10.6% of residents), and the population of second-generation immigrants at 4,473. Correspondingly, the numbers of foreign-born people acquiring Icelandic citizenship are markedly higher than in the 1990s, standing at 703 in 2016.[39][40] Correspondingly, Icelandic identity is gradually shifting towards a more multicultural form.[41]

Culture

Language and literature

Icelandic, a North Germanic language, is the official language of Iceland (de facto; the laws are silent about the issue). Icelandic has inflectional grammar comparable to Latin, Ancient Greek, more closely to Old English and practically identical to Old Norse.

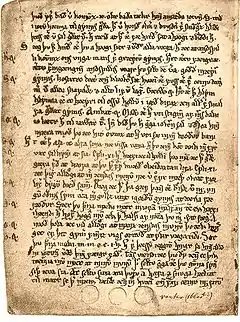

Old Icelandic literature can be divided into several categories. Three are best known to foreigners: Eddic poetry, skaldic poetry, and saga literature, if saga literature is understood broadly. Eddic poetry is made up of heroic and mythological poems. Poetry that praises someone is considered skaldic poetry or court poetry. Finally, saga literature is prose, ranging from pure fiction to fairly factual history.[42]

Written Icelandic has changed little since the 13th century. Because of this modern readers can understand the Icelanders' sagas. The sagas tell of events in Iceland in the 10th and early 11th centuries. They are considered to be the best-known pieces of Icelandic literature.[43]

The elder or Poetic Edda, the younger or Prose Edda, and the sagas are the major pieces of Icelandic literature. The Poetic Edda is a collection of poems and stories from the late 10th century, whereas the younger or Prose Edda is a manual of poetry that contains many stories of Norse mythology.

Religion

Iceland embraced Christianity in c. 1000, in what is called the kristnitaka, and the country, while mostly secular in observance, is still predominantly Christian culturally. The Lutheran church claims some 84% of the total population.[44] While early Icelandic Christianity was more lax in its observances than traditional Catholicism, Pietism, a religious movement imported from Denmark in the 18th century, had a marked effect on the island. By discouraging all but religious leisure activities, it fostered a certain dourness, which was for a long time considered an Icelandic stereotype. At the same time, it also led to a boom in printing, and Iceland today is one of the most literate societies in the world.[23][45]

While Catholicism was supplanted by Protestantism during the Reformation, most other world religions are now represented on the island: there are small Protestant Free Churches and Catholic communities, and even a nascent Muslim community, composed of both immigrants and local converts. Perhaps unique to Iceland is the fast-growing Ásatrúarfélag, a legally recognized revival of the pre-Christian Nordic religion of the original settlers. According to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Reykjavík, there were only approximately 30 Jews in Iceland as of 2001.[46] The former First Lady of Iceland Dorrit Moussaieff was an Israeli-born Bukharian Jew.

Cuisine

Icelandic cuisine consists mainly of fish, lamb, and dairy. Fish was once the main part of an Icelander's diet but has recently given way to meats such as beef, pork, and poultry.[22]

Iceland has many traditional foods called Þorramatur. These foods include smoked and salted lamb, singed sheep heads, dried fish, smoked and pickled salmon, and cured shark. Andrew Zimmern, a chef who has traveled the world on his show Bizarre Foods with Andrew Zimmern, responded to the question "What's the most disgusting thing you've ever eaten?" with the response "That would have to be the fermented shark fin I had in Iceland". Fermented shark fin is a form of Þorramatur.[47]

Performance art

The earliest indigenous Icelandic music was the rímur, epic tales from the Viking era that were often performed a cappella. Christianity played a major role in the development of Icelandic music, with many hymns being written in the local idiom. Hallgrímur Pétursson, a poet and priest, is noted for writing many of these hymns in the 17th century. The island's relative isolation ensured that the music maintained its regional flavor. It was only in the 19th century that the first pipe organs, prevalent in European religious music, first appeared on the island.[48]

Many singers, groups, and forms of music have come from Iceland. Most Icelandic music contains vibrant folk and pop traditions. Some more recent groups and singers are Voces Thules, The Sugarcubes, Björk, Sigur Rós, and Of Monsters and Men.

The national anthem is "Ó Guð vors lands" (English: "Our Country's God"), written by Matthías Jochumsson, with music by Sveinbjörn Sveinbjörnsson. The song was written in 1874, when Iceland celebrated its one thousandth anniversary of settlement on the island. It was originally published with the title A Hymn in Commemoration of Iceland's Thousand Years.[48]

Sports

Iceland's men's national football team participated in their first FIFA World Cup in 2018, after reaching the quarter finals of its first major international tournament, UEFA Euro 2016. The women's national football team has yet to reach a World Cup; its best result at a major international event was a quarterfinal finish in UEFA Women's Euro 2013. The country's first Olympic participation was in the 1912 Summer Olympics; however, they did not participate again until the 1936 Summer Olympics. Their first appearance at the Winter Games was at the 1948 Winter Olympics. In 1956, Vilhjálmur Einarsson won the Olympic silver medal for the triple jump.[49] The Icelandic national handball team has enjoyed relative success. The team received a silver medal at the 2008 Olympic Games and a 3rd place at the 2010 European Men's Handball Championship.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Icelander". Joshua Project. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "Population figures by country of citizenship". www.hagstofa.is. Statistics Iceland. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ↑ "Census Profile, 2016 Census Canada [Country]". Canada 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ↑ "Census 2000 ACS Ancestry" Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Map Analyser". Statistikbanken (in Danish). Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 World Migration. Archived 3 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. International organization for migration.

- ↑ Erwin Dopf. "Présentation de l'Islande, Relations bilatérales". diplomatie.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ "Iceland country brief". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ "United Nations Population Division | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ↑ "Populations by religious and life stance organizations 1998–2016". Reykjavík, Iceland: Statistics Iceland. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2017..

- ↑ "Icelanders, a diverse bunch?". www.genomenewsnetwork.org. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Helgason, A; Sigureth; Nicholson, J; et al. (September 2000). "Estimating Scandinavian and Gaelic ancestry in the male settlers of Iceland". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67 (3): 697–717. doi:10.1086/303046. PMC 1287529. PMID 10931763.

- ↑ Jónsson et al., 1991, pp. 17–23

- ↑ Þórðarson, c. 1200

- ↑ Fiske et al., 1972, p. 4

- ↑ "Icelandic Women are of Scots descent". Electricscotland.lcom. 4 March 2001. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "Why people in Iceland look just like us". irishtimes.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Þorgilsson, c. 1100

- ↑ Byock, 1990

- 1 2 Fiske et al., 1972, p. 5

- ↑ Global Volcanism Program, 2007

- 1 2 Stone, 2004

- 1 2 3 4 Fiske et al., 1972, p. 6

- ↑ Chadwick, R. (1999). "The Icelandic database—do modern times need modern sagas?". BMJ. 319 (7207): 441–444. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7207.441. PMC 1127047. PMID 10445931.

- ↑ Gísli Pálsson, 'The Web of Kin: An Online Genealogical Machine', in Kinship and Beyond: The Genealogical Model Reconsidered, ed. by Sandra C. Bamford, James Leach, Fertility, Reproduction and Sexuality, 15 (Berghahn Books, 2009), pp. 84–110 (pp. 100–103).

- ↑ Jagadeesan, Anuradha; et al. (2018). "Reconstructing an African Haploid Genome from the 18th Century". Nature Genetics. 50 (2): 199–205. doi:10.1038/s41588-017-0031-6. PMID 29335549. S2CID 9685229.

- ↑ Ebenesersdóttir, S. Sunna; Sandoval-Velasco, Marcela; Gunnarsdóttir, Ellen D.; Jagadeesan, Anuradha; Guðmundsdóttir, Valdís B.; Thordardóttir, Elísabet L.; Einarsdóttir, Margrét S.; Moore, Kristjan H. S.; Sigurðsson, Ásgeir; Magnúsdóttir, Droplaug N.; Jónsson, Hákon; Snorradóttir, Steinunn; Hovig, Eivind; Møller, Pål; Kockum, Ingrid; Olsson, Tomas; Alfredsson, Lars; Hansen, Thomas F.; Werge, Thomas; Cavalleri, Gianpiero L.; Gilbert, Edmund; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Walser, Joe W.; Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Árnadóttir, Lilja; Magnússon, Ólafur Þ.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Stefánsson, Kári; Helgason, Agnar (2018). "Ancient genomes from Iceland reveal the making of a human population". Science. 360 (6392): 1028–1032. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1028E. doi:10.1126/science.aar2625. hdl:10852/71890. PMID 29853688..

- ↑ Árnason et al., 2000

- ↑ Sigríður Sunna Ebenesardóttir; et al. (10 November 2010). "A new subclade of mtDNA haplogroup C1 found in Icelanders: Evidence of pre-Columbian contact?". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 144 (1): 92–9. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21419. PMID 21069749.

- ↑ Skov, L.; Macià, M. C.; Sveinbjörnsson, G.; et al. (2020). "The nature of Neanderthal introgression revealed by 27,566 Icelandic genomes". Nature. 582 (7810): 78–83. Bibcode:2020Natur.582...78S. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2225-9. PMID 32494067. S2CID 216076889.

- ↑ Helgason et al., 2000

- ↑ Ebenesersdóttir, S. Sunna; Sandoval-Velasco, Marcela; Gunnarsdóttir, Ellen D.; Jagadeesan, Anuradha; Guðmundsdóttir, Valdís B.; Thordardóttir, Elísabet L.; Einarsdóttir, Margrét S.; Moore, Kristjan H. S.; Sigurðsson, Ásgeir; Magnúsdóttir, Droplaug N.; Jónsson, Hákon; Snorradóttir, Steinunn; Hovig, Eivind; Møller, Pål; Kockum, Ingrid; Olsson, Tomas; Alfredsson, Lars; Hansen, Thomas F.; Werge, Thomas; Cavalleri, Gianpiero L.; Gilbert, Edmund; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Walser, Joe W.; Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Árnadóttir, Lilja; Magnússon, Ólafur Þ.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Stefánsson, Kári; Helgason, Agnar (2018). "Ancient genomes from Iceland reveal the making of a human population". Science. 360 (6392): 1028–1032. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1028E. doi:10.1126/science.aar2625. hdl:10852/71890. PMID 29853688.. "[R]eproductive success among the earliest Icelanders was stratified by ancestry... [M]any settlers of Gaelic ancestry came to Iceland as slaves, whose survival and freedom to reproduce is likely to have been constrained... [Scandinavians] likely contributed more to the contemporary Icelandic gene pool than the other pre-Christians."

- ↑ Tomasson, pp. 405–406.

- ↑ Jackson, May 1925, pp. 680–681.

- ↑ Jackson, May 1925, p. 681.

- ↑ "Island History and Culture". Washington Island. 1996. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Library of Congress, 2004

- ↑ Vanderhill, 1963

- ↑ Loftsdóttir, Kristín (2017). "Being 'the Damned Foreigner': Affective National Sentiments and Racialization of Lithuanians in Iceland" (PDF). Nordic Journal of Migration Research. 7 (2): 70–77 [72]. doi:10.1515/njmr-2017-0012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ 'Immigrants and persons with foreign background 2017' (16 June 2017).

- ↑ Gunnarsson, Gunnar J.; Finnbogason, Gunnar E.; Ragnarsdóttir, Hanna; Jónsdóttir, Halla. "Friendship, Diversity and Fear: Young People's Life Views and Life Values in a Multicultural Society". Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education. 2015: 94–113.

- ↑ Lahelma et al., 1994–96

- ↑ Lovgren, 2004, p. 2

- ↑ Jochens, 1999, p. 621

- ↑ Del Giudice, 2008

- ↑ Roman Catholic Diocese of Reykjavík, 2005.

- ↑ Beale et al., 2004

- 1 2 Fiske et al., 1972, p. 9

- ↑ Fiske et al., 1972, p. 7

References

- Einar Árnasson; Hlynur Sigurgíslasson; Eiríkur Benedikz (2000). "Genetic homogeneity of Icelanders: fact or fiction?". Nature Genetics. 25 (4): 373–374. doi:10.1038/78036. PMID 10932173. S2CID 28507476.

- Beale, Lewis, Daily, Laura (2004). "Food: Confessions of a celebrity chef". USA Today. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Byock, Jesse L. (1990). Medieval Iceland. Society, Sagas, and Power. United States: University of California Press.

- Del Giudice, Marguerite (March 2008). "Power Struggle". National Geographic.

- Fiske, John; Rolvaag, Karl (1972). Lands and Peoples: Iceland. United States: Grolier.

- Global Volcanism Program (GVP), Smithsonian Institution (2007). "Grímsvötn". Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- Agnar Helgason; Sigrún Sigurðardóttir; Jeffrey R. Gulcher; Ryk Ward; Kári Stefánsson (February 2000). "mtDNA and the Origin of the Icelanders: Deciphering Signals of Recent Population History". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (3): 999–1016. doi:10.1086/302816. PMC 1288180. PMID 10712214.

- Jackson, Thorstina (May 1925). "Icelandic Communities in America: Cultural Backgrounds and Early Settlements". Journal of Social Forces. 3 (4): 680–686. doi:10.2307/3005071. JSTOR 3005071. S2CID 147332269.

- Jackson, Thorstina (December 1925). "The Icelandic Community in North Dakota Economic and Social Development Period 1878-1925". Social Forces. 4 (2): 355–360. doi:10.2307/3004589. JSTOR 3004589.

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313309847. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- Bergsteinn Jónsson; Björn Þorsteinsson (1991). Íslandssaga til okkar daga (in Icelandic). Reykjavík, Iceland: Sögufélag. ISBN 978-9979-9064-4-5.

- Jochens, Jenny (1999). "Late and Peaceful: Iceland's Conversion Through Arbitration in 1000". Speculum. 74 (3): 621–655. doi:10.2307/2886763. JSTOR 2886763. S2CID 162464020.

- Library of Congress (2004). "Immigration...Scandinavian: The Icelanders". Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- Antii Lahelma; Johan Olafsson (1994–1996). "Nordic FAQ – 5 of 7 – Iceland". Internet FAQ Archives. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- Lovgren, Stefan (7 May 2004). ""Sagas" Portray Iceland's Viking History". National Geographic.

- Marcus, G. J. (1957). "The Norse Traffic with Iceland". The Economic History Review. 9 (3): 408–419. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1957.tb00672.x.

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Reykjavík (2005). "Statistical Report for Iceland: 2000-2001". Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- Simpson, Bob (2000). "Imagined Genetic Communities: Ethnicity and Essentialism in the Twenty-First Century". Anthropology Today. 16 (3): 3–6. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.00023.

- Stone, Richard (2004). "Iceland's Doomsday Scenario?". Science. 306 (5700): 1278–1281. doi:10.1126/science.306.5700.1278. PMID 15550636. S2CID 161557686.

- Stone, George (2005). "48 Hours Reykjavík: The Best of a City in Two Days". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 6 December 2003. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- Tomasson, Richard F. (1977). "A Millennium of Misery: The Demography of the Icelanders". Population Studies. 31 (3): 405–427. doi:10.2307/2173366. JSTOR 2173366. PMID 11630504.

- Vanderhill, Burke G.; David E. Christensen (1963). "The Settlement of New Iceland". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 53 (3): 350–363. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1963.tb00454.x.