Igal Roodenko | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 8, 1917 New York City, New York, USA |

| Died | April 28, 1991 (aged 74) New York City, New York, USA |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Cornell University |

| Known for | War Resisters League; Committee for Nonviolent Revolution; Journey of Reconciliation |

Igal Roodenko (February 8, 1917 – April 28, 1991) was an American civil rights activist, and pacifist.

A life of conscience

Igal Roodenko was born on February 8, 1917, in New York City. His parents, Morris (Moishe) and Ida (Ita)(nee Gorodetsky) were from Zhitomir, near Kiev, in present day Ukraine. They fled persecution under the Russian Tsar, and emigrated to Palestine in 1914, leaving there soon after to escape the Turks drafting Roodenko's father into WW1. They arrived in New York City in 1916, rejoining many members of their family who'd arrived a short time earlier. Morris Roodenko started with a push-cart on the Lower East Side, and eventually had a small dry goods shop.

Roodenko decided to become a vegetarian at a young age, and his entire family followed suit - mother, father, and younger sister. He was raised in a Zionist, Socialist, vegetarian home. He graduated from Townsend Harris High School in Manhattan, New York.[1] where he was active in theater. He attended Cornell University from 1934 to 1938, where he received a degree in horticulture, with the intention of taking these skills to Palestine. However, at the university he became a pacifist and decided to stay in the United States: "aware of the conflict between my pacifism and my Zionism, and then ceased being a nationalist."

Roodenko was a pacifist and a follower of Gandhi. It was Gandhi’s dramatic acts of civil disobedience that, at least in part, inspired the Journey of Reconciliation (see below) and - the rest of his life. He was a Conscientious Objector during WW2; he was very active in anti-Hitler activities before the United States joined the war, but did not believe in conscription, so he ended up in federal prison for 20 months. Early in the war, he was sent to a camp in Montezuma County, Colorado to perform Civilian Public Service in lieu of military service. Roodenko's principles led him to refuse to work, which in turn led to his arrest, conviction, and imprisonment at the Federal Correctional Institution, Sandstone.[2] He sued the United States government, challenging the constitutionality of the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. On December 22, 1944, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit found against Roodenko,[3] and the United States Supreme Court denied a writ of certiorari on March 26, 1945.[4] He and conscientious objectors in six other federal prisons began a hunger strike on May 11, 1946, to draw attention to the plight of war resistors. Roodenko was not released from prison until January 1947.[2]

Roodenko was an early member of the Committee for Nonviolent Revolution, a pacifist group founded in New York City in 1946. Other prominent members included Ralph DiGia, Dave Dellinger, George Houser, and Bayard Rustin.[5]: 128 After his release from prison, Roodenko lived in a tenement at 217 Mott Street[6] on the Lower East Side of New York. Rustin rented an apartment one floor below Roodenko, and this proximity, along with the exceptional number of young radicals living on Mott Street and on nearby Mulberry Street and elsewhere in the neighborhood, enabled Roodenko's continuing activism.[5]: 175

For many years he was a printer and had his own shop in New York City. He became involved with the pacifist organization, the War Resisters League (WRL), and served on their executive committee from 1947 to 1977. In 1968 he became its Chairman til 1972. He eventually sold his print shop and devoted the rest of his life to the WRL while still printing their annual Peace Calendar. He traveled around the country and around the world speaking about peace and justice and pacifism. He spoke at schools and universities, houses of worship, conferences and rallies, and many times in his travels, he’d get arrested. He was a gifted speaker and a wonderful story teller. In his interview in 1974 for the Southern Oral History Program Collection he stated, "A great deal of talking and organizing - this is my major commitment now, not so much to the War Resisters League as an institution, but to the idea that the human species has two or three generations at most to learn to live with itself, and otherwise if we don't learn to deal with our conflicts in a non-lethal manner, we stand a very good chance of destroying ourselves, perhaps destroying all life on this planet. To me, the key word is non-violence. It is a much misused word, but until we find a better word, I am addicted to it."

Journey of Reconciliation

In April 1947, eight black and eight white men set out on a 2 week interstate bus trip from Washington, D.C. into the upper South called The Journey of Reconciliation, sponsored by the FOR (Fellowship of Reconciliation), and CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). Sitting Black and white side-by-side, they sought, in areas where local statues still upheld segregation, to test the new Supreme Court Morgan v. State of Virginia decision, which ruled that segregation on interstate travel was unconstitutional. 4 riders were arrested in Chapel Hill, NC - Bayard Rustin, Igal Roodenko, Joe Felmet and Andrew Johnson. At their trial, Rustin and Roodenko were both convicted. Rustin was sentenced to 30 days on a North Carolina chain gang. The judge said to Roodenko, "Now, Mr. Rodenky (sic), I presume you're Jewish." "Yes, I am," Roodenko replied. "Well, it's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down bringing your nigras with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson," the judge sentenced him to 90 days on a chain gang - three times the length of Rustin's sentence.[7]

On June 17, 2022, Judge Allen Baddour, with full consent of the State and Defense, dismissed the charges against the four Freedom Riders, with members of the exonerees’ families in attendance.[8] After 75 years the North Carolina court, vacated the convictions of four freedom fighters from the Journey of Reconciliation. Renee Price, chair of the Orange County Board of Commissioners, learned that the charges against these men arrested in Chapel Hill, in what many Civil Rights historians consider the first Freedom Ride, had never been dropped. "They were arrested and convicted for violating laws that were in fact a violation to humanity, a violation to human dignity and a violation to freedom and justice for all," said Price. She reached out to Orange County Superior Court Judge Allen Baddour, whose office researched the incident and legal cases. After 75 years, on June 17, 2022, Superior Court Judge Allen Baddour vacated and dismissed the charges in a Special Court Session which drew over 100 people into the very courtroom where the men were sentenced.

“We failed these men in Orange County, in Chapel Hill,” said Judge Baddour. “We failed their cause and we failed to deliver justice in our community. And for that, I apologize. So we’re doing this today to right a wrong, in public and on the record because these offenses, these events happened all over the country and very little documented evidence of the court process exists. I do not want to erase history, but we must shine a light on it.” Along with Judge Baddour and Renee Price, speakers included Woodrena Baker-Harrell, Public Defender, Orange & Chatham Counties; Jim Woodall, District Attorney, Orange & Chatham Counties; Chief Chris Blue, Chapel Hill Police Dept.; Pam Hemminger, Mayor Chapel Hill; LaTarndra Strong, President North Orange NAACP; Dr. Freddie Parker, Professor Emeritus of History, North Carolina Central Univ.; Walter Naegle, partner of Bayard Rustin; and Amy Zowniriw, niece of Igal Roodenko. “The 1947 Journey of Reconciliation was about speaking truth to power and confronting injustice nonviolently…. Their faith and their consciences compelled them to act,” said Naegle.

Zowniriw said, “He Roodenko devoted his life to changing the world for the better, sometimes one person at a time, and sometimes, at great risk to his own personal well-being. He told me many times that his favorite thing to do was to give a speech. So today I am honored both to speak to you and to speak for him.”

You Don't Have To Ride Jim Crow, Documentary: Seven of the original riders joined for a series of reunions in the production of this documentary. The program captures them as they retrace their steps to stand at the exact sites of events nearly 50 years before. At a former bus station in North Carolina, the riders recall a mob’s attack on them and the backroads on which they were spirited away. They visit the chain gang site and jails where they served time for the crime of sitting together on a bus. They also meet, for the first time, Mrs. Irene Morgan Kirkaldy, whose courage was the impetus for their Journey. Additionally, the program looks at the contributions of the participants beyond the Journey, including the March on Washington and scores of nonviolent actions that have changed the racial landscape of America.

Roodenko was arrested numerous other times throughout his life: in 1962 for leading a peace rally in Times Square (his sentence was suspended, as the judge was sympathetic with the aims of the protestors).[6] At other times for protesting against mistreatment of Soviet dissidents,[9] against Cornell University's investments in South Africa, and, in Poland in 1987, along with four other members of the WRL, for trying to strengthen organizational connections with Polish dissidents. In 1983, discussing the difficulties of political activism with a reporter from the New York Times, Roodenko memorably stated that "if it were easy, any schmo could be a pacifist."[10]

Personal life and death

Roodenko was a gay man.[11] At the time of his death, he was a member of Men of all Colors Together.[1]

Roodenko died on April 28, 1991, in Beekman Downtown Hospital in New York of a heart attack.[1] He is survived by his niece, Amy Zowniriw.

Awards

Roodenko was awarded the War Resisters League Peace Award in 1979.

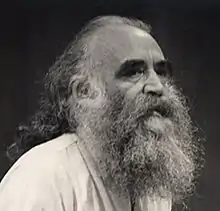

Igal Roodenko, date unknown, Louisville, KY

Igal Roodenko, date unknown, Louisville, KY Igal protesting war in Vietnam, July 4, 1966 in Copenhagen

Igal protesting war in Vietnam, July 4, 1966 in Copenhagen

References

- 1 2 3 "Igal Roodenko, 74; Led Anti-War Group". New York Times: D24. May 1, 1991.

- 1 2 Bennett, Scott H. (July 2003). "'Free American Political Prisoners': Pacifist Activism and Civil Liberties, 1945-48". Journal of Peace Research. 40 (4): 413–433. doi:10.1177/00223433030404004. JSTOR 3648291. S2CID 145734494.

- ↑ "Roodenko v. United States". findacase.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ↑ "United States Supreme Court". New York Times: 25. March 27, 1945.

- 1 2 D'emilio, John (June 25, 2007). Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-6790-5. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- 1 2 "Three Sentenced After Peace Rally". New York Times: 23. April 14, 1962.

- ↑ Whitfield, Stephen J. "Rethinking the Alliance between Blacks and Jews." In Raphael, Marc Lee (2001). "Jewishness" and the world of "difference" in the United States. Dept. of Religion, College of William and Mary. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ↑ Tom Foreman, Jr. (June 18, 2022). "Court posthumously vacates Freedom Riders' 1947 convictions in North Carolina". PBS NewsHour.

- ↑ "5 Seized Trying to Picket Soviets' U.N. Mission Here". New York Times: 36. December 31, 1967.

- ↑ Robbins, William (July 18, 1983). "Diverse Antiwar Movement Cites Gains". New York Times: A6.

- ↑ "Oral History Interview with Igal Roodenko Interview B-0010 (excerpt)". Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) in the Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. April 11, 1974. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

Further reading

- "Igal Roodenko Papers, 1935-1991", Document Group: DG 161, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

- Oral History Interview with Igal Roodenko (listen) or Oral History (read) at Oral Histories of the American South

- Remembering the only Jew on the first Freedom Ride – 75 years ago April 21, 2022 The Forward

- Early freedom riders, including pioneering Jewish activist, get justice after 75 years - The Forward June 2022

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - Carolina Public Humanities - 75th Anniversary of the Journey of Reconciliation