| Iliocostal friction syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Costoiliac impingement syndrome |

| |

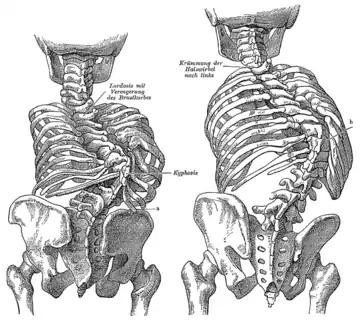

| Kyphosis (left) and scoliosis (right) depicting iliocostal contact (a) | |

| Symptoms | Pain in the lower rib, flank, groin, thigh, or buttocks. |

| Causes | Contact between the ribs and the iliac crest |

| Risk factors | Osteoporosis, hyperkyphosis, and scoliosis |

| Diagnostic method | Physical examination, x-ray, CT scan |

| Treatment | Orthosis, nerve blocks, prolotherapy, surgery |

Iliocostal friction syndrome, also known as costoiliac impingement syndrome, is a condition in which the costal margin comes in contact with the iliac crest. The condition presents as low back pain which may radiate to other surrounding areas as a result of irritated nerve, tendon, and muscle structures. It may occur unilaterally due to conditions such as scoliosis, or bilaterally due to conditions such as osteoporosis and hyperkyphosis.

Diagnosis is predominately clinical, with assessment into the underlying pathology causing iliocostal contact, to which radiological imaging may be used. The differential diagnosis can be extensive due to the presentation of the condition, however includes neuropathic pain, hip pathologies, pinched nerves, myofascial pain, and visceral causes. Treatment of the condition is typically by addressing the underlying cause, commonly with the use of orthosis and injection therapies, however surgical resection may be necessary if other forms of treatment fails to provide relief.

Presentation

Iliocostal friction syndrome can be a disabling painful condition that can affect the quality of life for individuals.[1] The predominant symptom is low back pain, which may radiate to the lower rib cage, flank, groin, buttock, and thigh.[2] Individuals may also experience intermittent aches along with a 'grating sensation' in the hip.[3] The pain may be aggravated by moving, twisting, bending, or by changing positions.[4] The condition may be bilateral as seen in individuals with hyperkyphosis or osteoporosis, but is more commonly unilateral as seen in individuals with scoliosis.[5]

Cause

Iliocostal friction syndrome is a result of the lower ribs coming in contact with the iliac crest due to a reduced costoiliac distance.[6] There are several conditions in which may cause iliocostal friction syndrome to occur both unilaterally or bilaterally.

Unilateral causes

Scoliosis has been known to cause unilateral iliocostal friction syndrome.[5] It is a condition in which the lateral curvature of the spine is measured to be more than 10 degrees. Scoliosis is typically categorized into congenital, neuromuscular, idiopathic, degenerative, and pathologic forms.[7] The decreased distance between the ribcage and the iliac crest can come in contact depending on the severity of the scoliosis curve.[8] There has also been reported instances where individuals experience iliocostal friction syndrome due to an abnormally long twelfth rib. This can be presented both bilaterally or unilaterally, depending on the individual.[3][8]

Bilateral causes

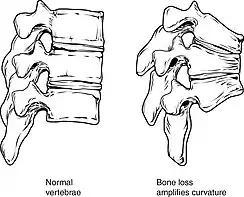

Iliocostal friction syndrome most commonly occurs bilaterally as a result of spinal osteoporosis.[2] Osteoporosis is a condition in which the bone density and quality deteriorates, resulting in an increased risk for fractures. More than 2 million fractures occur annually in the United States due to osteoporosis.[9] The most common fractures that occur due to osteoporosis is in the hip or vertebrae,[10] resulting in a loss of space between the ribs and the iliac crest. It is estimated that osteoporosis can cause 25% of females over 50 years of age within the United States to have at least one vertebral fracture in their lifetime.[11] Factors that make an individual more at risk for experiencing a fracture includes age, sex, weight, height, family history, rheumatoid arthritis, previous fracture, secondary osteoporosis, alcohol or smoking use, glucocorticoid use, and the femoral neck bone mineral density of the individual.[10]

Another cause for bilateral iliocostal contact is based on the kyphosis curve of the spine. The thoracic spine is slightly curved due to the shape of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, with a normal Cobb angle measurement between 20 and 40 degrees. Hyperkyphosis is a condition in which the curve of the kyphosis angle measures over 50 degrees. The kyphosis angle can be influenced by age, muscle tone,[12] vertebral fractures, and intervertebral degenerative disc disease.[13] Hyperkyphosis can result from posture, a congenital deformity, heritable conditions such as Scheuermann's disease,[14] tumours, trauma, neuro-muscular disease, postlaminectomy syndrome, dwarfism, and infections such as tuberculosis which can result in Pott's disease.[15] The curvature of hyperkyphosis may result in a decrease of space between the ribs and the iliac crest, causing iliocostal friction syndrome.[11]

Mechanism

Under normal conditions, there is no iliocostal contact due to enough distance between the lower ribs and the iliac crest. Individuals with iliocostal friction syndrome may have their 10th, 11th, or 12th rib come in contact with the iliac crest.[4] Structures of the body can be irritated as a result of iliocostal contact includes the nerves,[8] tendons, and muscles surrounding the area.[16]

There are several nervous branches surrounding the iliac crest that may be impinged or irritated upon contact. The superior cluneal nerves travel through the thoracolumbar fascia and drape over the iliac crest.[5] The posterior branches of the iliohypogastric nerve can emerge on the surface above the iliac crest, with the nerve draping lower than usual in some individuals.[8] Similarly, the ilioinguinal nerve runs below the iliohypogastric nerve, following just above the iliac crest.[17] These nerves may be impinged or irritated as a result of the lower ribs coming in contact with the iliac crest.[5]

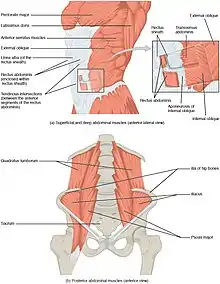

The top of the iliac crest includes the attachments of the latissimus dorsi, the transversus abdominis, as well as the internal and external obliques. The quadratus lumborum also connects from the back tip of the iliac crest up to the 12th rib.[18] These tendon and muscle structures surrounding the iliac crest are at risk for irritation due to iliocostal contact. Tendon irritation can result in referred pain, therefore affected individuals may experience pain throughout the hip, low back, the groin, chest, and thigh. This contributes towards the difficulty in diagnosis of iliocostal friction syndrome.[4]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of iliocostal friction syndrome can be made clinically without any imaging.[4] Typically, individuals with the syndrome will have an underlying condition such as scoliosis or osteoporosis in which may cause the iliocostal contact.[8] The examiner will assess for the possibility of contact by noting the medical history and reported symptomology by the individual. The clinician will examine the individual for iliocostal contact within a standing position and in movement.[4] Tenderness of the iliac crest and the lower ribs will be assessed with physical palpation.[16] Usually, flexion of the trunk laterally can trigger pain on the affected side(s), which is useful in diagnosis to pinpoint the exact location of iliocostal contact.[8]

Though radiological imaging is not needed for iliocostal friction syndrome diagnosis, it is often uses to assess for underlying conditions and rule out differential diagnosis. Imaging such as the use of an x-ray can reveal irregularities of the surfaces of the lower ribs and iliac crest or abnormally long 12th ribs, which may give suspicion to the diagnosis of iliocostal friction syndrome.[3][6] Computed tomography (CT) scans can reveal kyphotic deformities, including a reduced distance between the lower ribs and the iliac crest, giving rise to the possibility of iliocostal contact.[19]

Differential diagnosis

Since iliocostal friction syndrome can present in pain in many areas surrounding the back, flank, and abdomen, the differential diagnosis for the condition can be extensive. Some of the diagnosis include but not limited to neuropathic pain of the intercostal nerves, conditions of the hip, pinched nerves within the spine, myofascial pain, and visceral causes.[6] Differential diagnosis may also include an investigation into the pathology which caused the iliocostal contact if it is not previously known, such as undiagnosed scoliosis, back strain, osteoporosis, or a compression fracture.[4]

Iliocostal friction syndrome should also be differentiated from other conditions affecting the lower ribs such as slipping rib syndrome, which is a condition that involves the increased mobility of the 8th to 10th ribs at their interchondral joints. Additionally, hypermobile 11th and 12th ribs may cause twelfth rib syndrome due to the floating ribs impinging on the intercostal nerves (intercostal neuralgia). Neither of these conditions involve the iliac crest.[3]

Treatment

The most common method for treating iliocostal friction syndrome is usually with acupuncture,[16] physical therapy, muscle relaxants, and activity modification.[19] Treatment may involve addressing the underlying pathology of the condition as hyperkyphosis, osteoporosis and scoliosis may be treated with postural training and muscle strengthening methods. Orthosis, a specialty that involves individuals being fitted with a brace or harness may help correct the curvature of the spine.[6][20] Rib-compression belts have also been used as a conservative form of treatment for iliocostal friction syndrome. A 3-inch wide lower rib-compression belt is fitted above the iliac crests and tightly adjusted to provide pressure on the lower ribs. Since the lower ribs are attached to the sternum by flexible hyaline cartilage, they can be pushed inward with ease, and as a result, the compression shifts the ribs away from the iliac crests, preventing iliocostal contact.[2][4]

Local injections or nerve blocks containing steroids or lidocaine may also be used if other conservative methods of treatment have failed to provide adequate relief.[8] The injections are inserted into the junctions near the iliac crest as well as the lower rib margins,[2] and often have to be repeated as they only give relief for a short duration of time.[3] Prolotherapy has also been used to treat iliocostal friction syndrome, as the tendinous and muscle structures surrounding the iliac crest may be damaged as a result of iliocostal friction. Hypertonic dextrose is a common medication used in prolotherapy, sometimes diluted with lidocaine, which is injected along the iliac crest. Treatment is usually weekly or bi-weekly, and up to 6 sessions may be necessary to relieve tenderness in the area.[4] The most invasive method for treating iliocostal friction syndrome is the surgical resection of the floating ribs,[2] which excises the outer two-thirds of the rib while the individual is under anesthesia.[3] Special attention is made to preserve the intercostal nerve not to cause intercostal neuralgia.[8]

References

- ↑ Sinaki M, Pfeifer M (2017). Non-pharmacological management of osteoporosis: exercise, nutrition, fall and fracture prevention. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-3-319-54016-0. OCLC 990294268.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brubaker ML, Sinaki M (June 2016). "Successful management of iliocostal impingement syndrome: A case series". Prosthetics & Orthotics International. 40 (3): 384–387. doi:10.1177/0309364615605394. ISSN 0309-3646. PMID 26527757.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wynne AT, Nelson MA, Nordin BE (1985). "Costo-iliac impingement syndrome". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 67 (1): 124–125. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.67B1.3155743. ISSN 0301-620X. PMID 3155743.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hirschberg GG, Williams KA, Byrd JG (1992). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Iliocostal Friction Syndromes". Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine. 14 (2): 35–39. doi:10.1080/1355297X.1992.11719682. ISSN 1355-297X.

- 1 2 3 4 McAnally HB, Rescot AM (May 2020). "Superior Cluneal Neuralgia from Iliocostal Impingement Treated with Phenol Neurolysis: A Case Report". Pain Management Case Reports. 4 (3): 77–84. doi:10.36076/pmcr.2020/4/77. ISSN 2575-9841.

- 1 2 3 4 Patel SI, Jayaram P, Portugal S, et al. (July 2014). "Iliocostal Friction Syndrome Causing Flank Pain in a Patient with a History of Stroke with Scoliosis and Compensated Trendelenburg Gait". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 93 (7): 632–633. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e318282e939. ISSN 0894-9115. PMID 23370590.

- ↑ Blevins K, Battenberg A, Beck A (August 2018). "Management of Scoliosis". Advances in Pediatrics. 65 (1): 249–266. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2018.04.013. PMID 30053928. S2CID 51727835.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Huber P, Arroyo J (March 1995). "Syndrome algique ilio-costal". Douleur et Analgésie (in French). 8 (1): 25–27. doi:10.1007/BF03005024. ISSN 1951-6398. S2CID 71158860.

- ↑ Anthamatten A, Parish A (May 2019). "Clinical Update on Osteoporosis". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 64 (3): 265–275. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12954. ISSN 1526-9523. PMID 30869832. S2CID 76663413.

- 1 2 Ensrud KD, Crandall CJ (August 2017). "Osteoporosis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 167 (3): ITC17–ITC32. doi:10.7326/AITC201708010. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 28761958.

- 1 2 Rosen CJ, Glowacki J, Bilezikian JP (1999). The aging skeleton. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-12-098655-2. OCLC 162570766.

- ↑ Roghani T, Zavieh MK, Manshadi FD, et al. (August 2017). "Age-related hyperkyphosis: update of its potential causes and clinical impacts—narrative review". Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 29 (4): 567–577. doi:10.1007/s40520-016-0617-3. ISSN 1720-8319. PMC 5316378. PMID 27538834.

- ↑ Koelé MC, Lems WF, Willems HC (January 2020). "The Clinical Relevance of Hyperkyphosis: A Narrative Review". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 11: 5. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.00005. ISSN 1664-2392. PMC 6993454. PMID 32038498.

- ↑ Bettany-Saltikov J, Schreiber S (2017). Innovations in Spinal Deformities and Postural Disorders. [Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar]. p. 76. ISBN 978-953-51-3541-8. OCLC 1193044993.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Yaman O, Dalbayrak S (2013). "Kyphosis and review of the literature". Turkish Neurosurgery. 24 (4): 455–465. doi:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.8940-13.0. ISSN 1019-5149. PMID 25050667.

- 1 2 3 Marcus A (2004). Foundations for integrative musculoskeletal medicine : an east-west approach. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books. p. 655. ISBN 1-55643-540-1. OCLC 56657689.

- ↑ Elsakka KM, Das JM, Allam AE (2021), "Ilioinguinal Neuralgia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30855844, retrieved 2021-07-26

- ↑ Myers TW (2020). Anatomy Trains E-Book: Myofascial Meridians for Manual Therapists and Movement Professionals. United Kingdom: Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 79, 85. ISBN 9780702078149.

- 1 2 Banik RK, McDaniel E, DeWeerth JC, Sembrano JN (February 2021). "Iliocostal Friction Syndrome Due to Hair-Pin Shaped Thoracic Kyphosis". Pain Medicine. 22 (5): 1223–1224. doi:10.1093/pm/pnab027. ISSN 1526-2375. PMID 34019652.

- ↑ Braddom, RL (2010). Physical medicine and rehabilitation (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 926. ISBN 978-1-4377-0884-4. OCLC 502393170.