The Ilustrados (Spanish: [ilusˈtɾaðos], "erudite",[1] "learned"[2] or "enlightened ones"[3]) constituted the Filipino intelligentsia (educated class) during the Spanish colonial period in the late 19th century.[4][5] Elsewhere in New Spain (of which the Philippines were part), the term gente de razón carried a similar meaning.

They were late Spanish-colonial-era middle to upper class Filipinos, many of whom were educated in Spain and exposed to Spanish liberal and European nationalist ideals. The ilustrado class was composed of Philippine-born and/or raised intellectuals and cut across ethnolinguistic and racial lines—mestizos (both de Sangleyes and de Español), insulares, and indios, among others—and sought reform through "a more equitable arrangement of both political and economic power" under Spanish tutelage.

Stanley Karnow, in his In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines, referred to the ilustrados as the "rich Intelligentsia" because many were the children of wealthy landowners or inqulino (tenant) lessee families. They were key figures in the development of Filipino nationalism.[3][6][7][8][9][10]

History

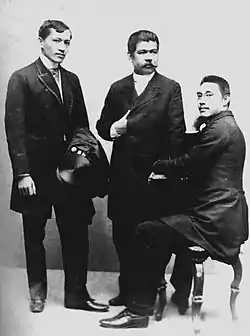

The most prominent ilustrados were Graciano López Jaena, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Mariano Ponce, Antonio Luna and José Rizal, the Philippine national hero. Rizal's novels Noli Me Tangere ("Touch Me Not") and El Filibusterismo ("The Subversive") "exposed to the world the injustices imposed on Filipinos under the Spanish colonial regime".[9][11]

In the beginning, Rizal and his fellow ilustrados preferred not to win independence from Spain, instead they wanted legal equality for both peninsulares and natives—indios, insulares, and mestizos, among others—in the economic reforms demanded by the ilustrados were that "the Philippines be represented in the Cortes and be considered a province of Spain" and "the secularization of the parishes."[10][11]

However, in 1872, nationalist sentiment grew strongest, when three Filipino priests, José Burgos, Mariano Gomez and friar Jacinto Zamora, who had been charged with leading a military mutiny at an arsenal in Cavite, near Manila, were executed by the Spanish authorities. The event and "other repressive acts and activities, Rizal was executed on December 30, 1896. His execution propelled the ilustrados. This also prompted unity among the ilustrados and Andrés Bonifacio's radical Katipunan.[10] Philippine policies by the United States reinforced the dominant position of the ilustrados within Filipino society. Friar estates were sold to the ilustrados and most government positions were offered to them.[10]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The American Heritage Spanish Dictionary (2nd ed.)

- ↑ RAE - ASALE. "Diccionario de la lengua española - Edición del Tricentenario". Diccionario de la lengua española.

- 1 2 Glossary: Philippines, Area Handbook Series, Country Studies, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, LOC.gov (undated), retrieved on: July 30, 2007

- ↑ Thomas, Megan Christine (2012). Orientalists, Propagandists, and Ilustrados: Filipino Scholarship and the End of Spanish Colonialism. U of Minnesota Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-8166-7190-8.

- ↑ Cullinane, Michael (1989). Ilustrado Politics: Filipino Elite Responses to American Rule, 1898-1908. Ateneo University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-439-3.

- ↑ Grimsley, Mark. The Philippine War: 1899-1902, Ohio-State.edu, 1993, 1996 Archived October 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley. In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines, Ballantine Books, Random House, Inc., March 3, 1990, 536 pages, page 15. - ISBN 0-345-32816-7

- ↑ The Rise of the Philippine Middle Class (Ilustrados), Mega Essays LLC, MegaEssays.com, 2007, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- 1 2 Philippines: The Spanish Colony, Student Encyclopedia Article, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., Britannica.com, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 History of the Philippines, Embassy of the Republic of the Philippines, Department of Foreign Affairs, PhilippineEmbassy-USA.org (undated, archived from the original on July 13, 2007), retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- 1 2 Salvador, Fr. Emerson, Liberalism in the Philippines, The Revolution of 1898: The Main Facts, Newsletter of the District of Asia, Society of St. Pius X, District of Asia, January - March 2002, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

Sources

- Republic of the Philippines, Microsoft Corporation, Encarta.MSN.com, 2007 ( (Archived 2009-10-31), retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Exiles, Motherland and Social Change, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal (Bibliography), Volume 8, Issue 1-2, SMC.org.ph, (undated), retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Owen, Norman G., Compadre Colonialism: Studies in the Philippines Under American Rule, A Review by Theodore Friend, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Nov., 1972), pp. 224-226, JSTOR.org, 2007, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Majul, Cesar A. The Political and Constitutional Ideas of the Philippine Revolution, A Review by R. S. Milne, Pacific Affairs, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Spring, 1969), pp. 98-99, JSTOR.org, 2007, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Proclamation of Philippine Independence and the Birth of the Philippine Republic, The Philippine History Site, OpManong.SSC.Hawaii.edu (undated) Archived August 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Rossabi, Amy. The Colonial Roots of Civil Procedure in the Philippines, Volume 11, Number 1, Fall 1997, The Journal of Asian Law, Columbia.edu, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Filipino Nationalism, AngelFire.com (undated), retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Veneracion, Jaime B., Ph. D. (Professor of History, University of the Philippines and Visiting Professor, BSU), Rizal's Madrid: The Roots of the Ilustrado Concept of Autonomy, Diyaryo Bulakenya, Bahay Saliksikan ng Bulakan (Center for Bulacan Studies), Geocities.com, April 4, 2003, retrieved on: August 1, 2007

- Philippine History, Philippine Children's Foundation, PhilippineChildrensFoundation.org, 2005, retrieved on: August 1, 2007