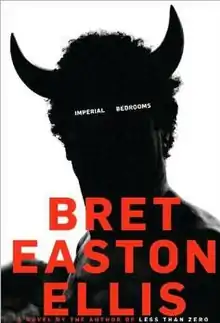

Cover of Imperial Bedrooms | |

| Author | Bret Easton Ellis |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Chip Kidd |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Literary fiction |

| Publisher | Knopf |

Publication date | June 15, 2010[1] |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 169 |

| ISBN | 0-307-26610-9 |

| Preceded by | Less than Zero |

Imperial Bedrooms is a novel by American author Bret Easton Ellis. Released on June 15, 2010, it is the sequel to Less than Zero, Ellis' 1985 bestselling literary debut, which was shortly followed by a film adaptation in 1987. Imperial Bedrooms revisits Less than Zero's self-destructive and disillusioned youths as they approach middle-age in the present day. Like Ellis' earlier novel, which took its name from Elvis Costello's 1977 song of the same name, Imperial Bedrooms is named after Costello's 1982 album.

The action of the novel takes place twenty-five years after Less than Zero. Its story follows Clay, a New York-based screenwriter, after he returns to Los Angeles to cast his new film. There he becomes embroiled in the sinister world of his former friends and confronts the darker aspects of his own personality. The novel opens with a literary device which suggests the possibility that the narrator of Imperial Bedrooms may not be the same as the narrator of Less than Zero although both are ostensibly narrated by Clay. In doing this, Ellis is able to comment on the earlier novel's style and on the development of its moralistic film adaptation. In the novel Ellis explores Clay's pathological narcissism, masochistic and sadistic tendencies, and exploitative personality, which had been less explicit in Less than Zero. Ellis chose to do this in part to dispel the sentimental reputation Less than Zero has accrued over the years, that of "an artifact of the 1980s". Imperial Bedrooms retains Ellis' characteristic transgressive style and applies it to the 2000s (decade) and 2010s, covering amongst other things, the impact of new communication technologies on daily lives.

Ellis began working on what would become Imperial Bedrooms during the development of his 2005 novel, Lunar Park. As with his previous works, Imperial Bedrooms depicts scenes of sex, extreme violence and hedonism in a minimalist style devoid of emotion. Some commentators have noted however that unlike previous works, Imperial Bedrooms employs more of the conventional devices of popular fiction. Reviews were mixed and frequently polarized. Some reviewers felt the novel was a successful return to themes explored in Less than Zero, Lunar Park and American Psycho (1991), while others derided it as boring or self-indulgent.

Background

The development of Imperial Bedrooms began after Ellis had re-read Less than Zero during the writing of his 2005 pseudo-memoir, Lunar Park. The novel takes its name from Elvis Costello's 1982 album Imperial Bedroom, just as Less than Zero had been named for a Costello single. Upon reading Zero, Ellis began to reflect on how his characters would have developed in the interim. Soon, he found himself "overwhelm[ed]" by the idea of what would become Imperial Bedrooms as it continually returned to him.[2] After gestating the idea, and making "voluminous notes", Ellis realised that his detailed outline had become longer than the finished book. He felt that this process of note-taking limited him to the novels that he genuinely wanted "to stay with for a couple of years". To this, he attributed having "written so few novels".[3]

Ellis described the novel as an "autobiographical noir [written] during a midlife crisis".[4] His most significant literary influence was American novelist Raymond Chandler, citing his particular brand of pulpy noir fiction.[5] He found particular inspiration in the opacity of Chandler's fiction, citing the lack of closure in some of the books, which he called "existentialist masterpieces." He also admired the cynical worldview that Chandler created, and his particular sense of style and mood.[6] In terms of his own plotting, however, he opined that "plots really don't matter", nor solutions to mysteries, because it's "the mood that's so enthralling... [a] kind of universal, this idea of a man searching for something or moving through this moral landscape and trying to protect himself from it, and yet he's still forced to investigate it." Part of the "impetus" behind Imperial Bedrooms, which Ellis "wrestled with", was to try and dispel the "sentimental" view of Less than Zero that made it, to some, "an artifact of the 80s" alongside "John Hughes movies and Ray-Bans and Fast Times at Ridgemont High"; he felt he began assessing audience's reactions to his work when working on Lunar Park.[5]

On April 14, 2009, MTV News announced that Ellis had nearly finished the novel and it would be published in May 2010. At the time, Ellis revealed that all the novel's main characters would return.[7][8][9][10] Prior to publication, Ellis had been convinced by his persuasive editor to remove some of the more graphic lines from Imperial Bedrooms' torture scenes, which he later regretted. "My most extreme act of self-censoring in Imperial Bedrooms," he said, however, was to omit a three-line description of a silver wall, because he felt that Clay would never have written it. Ellis stated he had no plans to make changes to the book as it stands in a second edition.[11] Months prior to the book's release, Ellis tweeted the first sentence of the novel, "They had made a movie about us."[12] The Random House website later announced the on sale date of June 22, 2010, in both hardback and paperback. With it, they released a picture of the book's cover and a short synopsis, which described the book as focusing on a middle-aged Clay, now a screenwriter, drawn back into his old circle. Amidst this, Clay begins dating a young actress with mysterious ties to Julian, Rip, and a recently murdered Hollywood producer; his life begins to spin out of control.[13] In Imperial Bedrooms, Los Angeles returns once again as the book's setting. It is, along with New York, one of the two major locations in Ellis' fiction.[11]

Plot

The action of Imperial Bedrooms depicts Clay, who, after four months in New York, returns to Los Angeles to assist in the casting of his new film. There, he meets up with his old friends who were characters in Less than Zero. Like Clay, they have all become involved in the film industry: his philandering friend Trent Burroughs—who has married Blair—is a manager, while Clay's former classmate at Camden, Daniel Carter, has become a famous director. Julian Wells, who was a male prostitute in Less than Zero, has become an ultra-discreet high-class pimp representing struggling young actors who do not wish to tarnish future careers. Rip Millar, Clay's former drug dealer, now controls his own cartel and has become disfigured through repeated plastic surgeries.

Clay attempts to romance Rain Turner, a gorgeous young woman auditioning for a role in his new film, leading her on with the promise of being cast, all the while knowing she will never get the part because of her complete lack of acting skills. His narration reveals he has done this with a number of men and women in the past, and yet often comes out of the relationship hurt and damaged himself. Over the course of their relationship, he is stalked by unknown persons driving a Jeep and is frequently reminded by various individuals of the grisly murder of a young producer whom he knew.

As the novel progresses, Clay learns that Rip also had a fling with Rain and is now obsessed with her. When Clay discovers that Julian is currently Rain's boyfriend, he conspires with Rip to hand Julian over to him. When Julian is then found murdered, Rain confronts Clay about his role in the affair and is raped by him in response. He later receives a video of Julian's murder from Rip which has been overdubbed with an angry voicemail from Clay as a means to implicate him in the crime. The novel then depicts sequences of the savage sexual and physical abuse of a beautiful young girl and young boy, perpetrated by Clay. Clay experiences no feelings of remorse or guilt for this, or for exploiting and raping Rain. In the last scenes, it is strongly implied that Blair has been hiring people to follow Clay. In return for his giving her what she wants, she offers to provide Clay with a false alibi that will prevent the police from arresting him as an accomplice to Julian's murder.

Characters

Much critical attention has been given to the development of the characters from the original book, 25 years on. One review opined that "[Ellis'] characters are incapable of growth. They cannot credibly find Jesus or even see a skilled psychologist or take the right medication to fend off despair. They are bound to be American psychos." Their development, some critics have observed, illuminates the ways they have not developed as people; Clay is, for example, "in mind and spirit if not quite in body, destined to remain unchanged, undeveloped, unlikable and unloved."[14] In Less than Zero, though the characters of the novel compose for some "the most hollow and vapid representation of the MTV generation one could possibly imagine",[15] they remained to other reviewers "particularly sympathetic".[16] Like the novel, its characters were equally cultural milestones, described by a reviewer as "seminal characters" (of American fiction). On the subject of the 1987 film, Clay describes that "the parents who ran the studio would[n't] ever expose their children in the same black light the book did". To Bill Eichenberger, this shows how "the children have become the parents, writing scripts and producing movies, still imprisoned by Hollywood's youth and drug cultures – but now looking at things from the outside in."[14] Eisinger comments for the New York Press, that while "they're in careers now and new relationships and different states of mind... their preoccupations are just the same."[15]

Clay, the protagonist of Less than Zero, "once a paralyzed observer, is now a more active character and has grown to be a narcissist".[3] The reason behind this shift in character personality was due to Ellis's lack of interest in the other characters—thus the solipsism is mirrored in the fiction. For Ellis, this became "an exploration of intense narcissism."[17] In 2010, Clay is now a "successful screenwriter" with the "occasional producer credit".[3] He returns to LA to help cast The Listeners (reminiscent of Ellis' involvement with the 2009 film adaptation of his short story collection The Informers).[18] Now 45, and no longer a disaffected teen, Clay is described by Details as "arguably worse than American Psycho's Patrick Bateman"; Ellis says that he would not disagree with this, citing the ambiguous nature of Bateman's crimes.[17] In terms of Clay's psychology, Ellis notes his preponderance for a "masochistic cycle of control and rejection and seduction and inevitable pain", which "is something he gets off on because he's ...a masochist and not a romantic."[6] The Los Angeles Times notes how Clay "shares biographical details with Ellis", a successful party-boy, who in 1985 was "often conflated with his fictional counterpart."[3] Ellis asserts to the contrary, "I'm not really Clay."[5] As opposed to his portrayal in Less than Zero, Clay is more unambiguously manipulative in Bedrooms; he is, in Ellis' words, "guilty".[3] As in Zero, Clay has stagnated in an impassive and jaded state, abusing alcohol and sedatives such as ambien, "living with a kind of psychic "locked-in" syndrome."[19] As in Zero and Psycho, the novel also poses the question of Clay's perception of reality, The Independent asking "Is Clay really being followed or is he being dogged by a guilty conscience for crimes committed, even when they are crimes of inaction?"[19] Over the novel, "Clay shifts from damaged to depraved";[16] a "final scene in Imperial Bedrooms of unremitting torture... enacted by Clay on two beautiful teenagers who are bought and systematically abused" demonstrates "Clay's graduation from a passively colluding observer to active perpetrator... who either indulges in torture or fantasizes about it."[19]

The novel is written in the first-person, from Clay's perspective. Clay, who "felt betrayed by Less than Zero", uses Imperial Bedrooms to make a stand or a case for himself, though ultimately "reveals himself to be far worse than the author of Less Than Zero ever began to hint at."[11] Clay still bears similarities to the earlier character in Less than Zero; according to one reviewer, "not all that much is changed. Clay is a cipher, an empty shell who is only able to approximate interactions and experiences through acts of sadism and exploitation." He is also, in many ways, a new character, because the opening of the book presents that the Clay of Less than Zero had merely been "just a writer pretending to be him".[20] When asked why he "changed" Clay from "passive" to "guilty", Ellis explained he felt Clay's inaction in the original novel made him equally as guilty; it had "always bothered" Ellis that Clay didn't do anything to save the little girl being raped in the first novel.[2] The Independent notes "his passivity [in Less than Zero] has hardened into something far more culpable, and nefarious."[19] According to Ellis, "In LA, over time, the real person you are ultimately comes out." He also speculates "maybe the fear turned him into a monster". Ellis remarks that he finds the developments in Clay "so exciting".[5] One reviewer summarized the character's development, "The nascent narcissist of Less Than Zero... is now left in a "dead end". The novel is Ellis'"deeply pessimistic presentation of human nature as assailable... an unflinching study of evil."[19]

Blair and Trent Burroughs share a loveless marriage.[14] Blair remains, according to Janelle Brown, "the moral center of Ellis' work", and Trent has become a Hollywood manager. The Oregonian notes "Although Blair and Trent have children, the children are never described and hardly mentioned; their absence is "even more unsettling than the absence of parents in a story about teenagers, underlining the endlessly narcissistic nature of the characters' world."[21] Julian Wells has gone on to establish a very exclusive escort service of his own in Hollywood.[18] While in Less than Zero, Clay felt protective of Julian, who had fallen into prostitution and drug addiction, in the new novel, he attempts to have him killed.[3] The "grisly" dispatch of Julian late in the book, and Clay's casual mention of it early on, were part of a "rhythm" that Ellis felt suited the book. He speculates whether "the artist looking back" becomes a destructive force. He hadn't planned to kill off the character, just finding that while writing "it felt right".[5] Rip Millar occupies both terrifying and comic relief roles in the novel. Vice describes him, hyperbolically, as "like the supervillain of these two books". Uncertainties about the character's "specifics" originate in Clay, who "doesn't really want to know, which makes it kind of scarier".[5]

Writing style

Writing for The Observer, Alison Kelly of the University of Oxford observed the novel's philosophical qualities, and opined that its "thriller-style hints and foreshadowings... form part of a metaphysical investigation." Kelly describes it as an exposé of the worst depths of human nature, labelling it "'existentialist' to the extent that it confronts the minimal limits of identity". She further argues that the novel's motif of facial recognitions amounts to the message that people should be read "at face value", and that furthermore, past action is the greatest indicator of future behaviour, leaving no room for "change, growth, [or] self-reinvention". In terms of stylistic literary changes, Ellis also displays more fondness for the Ruskinian pathetic fallacy than in previous works.[22] For the most part, the novel is written in Ellis' trademark writing style; Lawson refers to this as "sexual and narcotic depravities in an emotionless tone." With regard to this style, Ellis cites precursors to himself, particular the work of filmmakers. Ellis feels that the technique itself gives the reader a unique kind of insight into the characters, and comments that "numbness is a feeling too. Emotionality isn't the only feeling there is."[11] In terms of style, Ellis told Vice that he enjoyed his return to minimalism, because of the challenge of "[t]rying to achieve that kind of tension with so few words was enjoyable to do."[5] While some reviewers of popular fiction derided Ellis's style as "flat",[23] others found it unexpectedly moving.[24]

Literary devices and themes

Imperial Bedrooms opens with an acknowledgement from Clay, the main character, that both the Less than Zero novel and its film adaptation are actual representational works within the narrative of his life: "The movie was based on a book by someone we knew... It was labeled fiction but only a few details had been altered and our names weren't changed and there was nothing in it that hadn't happened." The Los Angeles Times described this as a "nifty little trick", as it allows Ellis to establish the newer book "as the primary narrative, one that trumps Ellis as author and the real world."[3] The San Francisco Chronicle calls it a "neat trick of authorial self-abnegation".[18] Another reviewer describes it as Ellis at "his most ambitious", a "Philip Rothian, doppelgänger gambit", making his new narrator "the real Clay" and the other an imposter.[20] This allows Ellis to skilfully, "with writerly jujitsu", acknowledge Robert Downey Jr.'s popular performance as Julian in the moralistic 1987 film, in which he died;[3] Ellis appreciates the adaptation as a "milestone in a lot of ways".[5] The device also allows the novelist to insert self-critique; The Sunday Times reviewer notes that Imperial Bedrooms finds its characters "still a little sore at their depiction as inarticulate zombies".[24] John Crace, in his "digested read" of Imperial Bedrooms, insinuates through parody that "the author" of the metafictional Less than Zero is also meant to be Ellis, describing him in Clay's voice as "too immersed in the passivity of writing and too pleased with his own style to bother with many commas to admit it so he wrote me into the story as the man who was too frightened to love."[25] With regard to the opening narrative conceit, Ellis queries "Is it complication ... or is it clarification?", opining that it certainly is the latter for Clay. Even though Ellis never names himself explicitly in the book, he conceded to Lawson that one can "guess [Bret Easton Ellis] is who the Clay of Imperial Bedrooms is referring to."[11] Ellis did, however, reveal that he had not decided when writing the novel whether Clay was referring to him or not.[5] Eileen Battersby likened Bedrooms to Lunar Park (2005), cited his use of "self-consciousness as a device."[16] This device was picked up on by several other critics—in particular, Vice noted that "the scatological violence of American Psycho" and "the otherworldly terror of Lunar Park" had here been combined. Ellis himself raised the "sequel" question, commenting "... I don't think it is [a sequel]. Well, I mean, it is and it isn't. It's narrated by him, sure. But I guess I could maybe have switched the names around and it could stand alone."[5]

Asked about the motif and "casual approach to" bisexual characters in his novels, continued in Imperial Bedrooms, Ellis stated he "really [didn't] know", and that he wished he could provide "an answer – depicting [him] as extremely conscious of those choices". He believes it to be an "interesting aspect of [his] work". Details notes how Ellis' own sexuality, frequently described as bisexual, has been notoriously hard to pin down.[17] Reviewers have long tried to probe Ellis on autobiographical themes in his work. He reiterates to Vice that he is not Clay. Ellis says that other contemporary authors (naming Michael Chabon, Jonathan Franzen, Jonathan Lethem as examples) don't get asked if their novels are autobiographical.[5] (However, Ellis tells one interview, that he "cannot fully" say that "I'm not Clay" because of their emotional "connections".)[6] Vice attributes this streak to Ellis' age when Less than Zero came out, which led to him being seen as a voice-of-the-generation. Ellis feels that the autobiographical truths of his novels lie in their writing processes, which to him are like emotional "exorcisms".[6] Crace's abovementioned parody suggests that Less than Zero Clay was originally a flattering portrayal of Ellis.[25] Ellis discusses lightly the kinds of self-insertion present in the book. While Clay is clearly (parodically) working on the film adaptation of The Informers, he is at the same time fully aware that he has been a character in Less than Zero, and that ostensibly, Ellis is 'the author' whom Clay knew. However, there are clear differences to the characters, as well. For example, Ellis had to omit lines from the book he felt Clay would never have thought of, on subjects he would never have noticed. Ellis himself feels he is adapting to middle-age very well; Clay, however, isn't.[11]

Imperial Bedrooms also breaches several new territories. When compared to Less than Zero, its "huge shift" is a technological one. The novel picks up on many aspects of the early 21st-century culture, such as Internet viral videos which depict executions. The novel reflects how technology changes the nature of interpersonal relationships. Additionally, Clay is text-stalked throughout the book; Ellis himself had been "text-stalked" before in real life. Ellis feels this was an unconscious exploration of the dynamics brought on by the new technology.[11] The author also predicts that "fans of Less Than Zero" may "feel betrayed"; Imperial Bedrooms' thrust is its "narrative... of exploitation".[3] One reviewer describes the novel's "central theme" as "Hollywood is an industry town running on exploitation", and criticizes this theme for being unoriginal in 2010.[20] An Irish Times review notes positively however that Ellis'"vision of society is bleak; his dark studies of the human animal as shocking as ever." The new setting poses questions, such as "Is Hollywood intended as a variation of ancient Rome? Is the movie industry a coliseum?"[16] Another review found that the celebrity setting, as visited before in his novel Glamorama (1998), allows Ellis to make a number of observations about contemporary pop culture via Clay, such as when he asserts "that exposure can ensure fame".[14] Ellis comments how in Less than Zero, Clay's passivity worked to protect him from the "bleak moral landscape he was a part of", which he views as Clay's major flaw. Ellis developed this into the more unabashedly 'guilty' Clay of the new novel. Ellis says that "a portrait of narcissism was the big nut that I had. Of entitlement. This imperial idea." The difference he notes between this "portrait of a narcissist" and his earlier ones, such as American Psycho and Lunar Park, come in the form of its more moral bent: "This time", Ellis comments, "the narcissist reaches a dead end."[2] To one reviewer, Clay's world at its most exaggerated, in the scenes of torture, reach Huxleyan heights of dystopian fantasy, comparing Imperial Bedrooms to Brave New World (1932), "where the "command economy" now manifests as rampant, late-capitalist consumerism, where ambien is the new soma and humans are zombies: one character's face is "unnaturally smooth, redone in such a way that the eyes are shocked open with perpetual surprise; it's a face mimicking a face, and it looks agonized."[19]

Reception

The Guardian attempted to aggregate what they found to be polarised reviews of Imperial Bedrooms, noting that one Times reviewer felt the novel was simply dull, "impoverished", and "ghastly", whereas the London Review of Books felt that in spite of its flaws, the book was enjoyable for its "beautiful one-liners" and the fun of "seeing the old Easton Ellis magic applied to the popular culture of our era ... iPhones, Apple stores, internet videos and Lost."[26] The New Statesman compiled reviews from The Independent, The Observer, and The New York Times. The first two reviews are positive, praising Ellis' "modern noir", the book's "atmosphere", and indebtedness to Philip Roth and F. Scott Fitzgerald, with the Observer saying it "ranks with his best in the latter register [of Fitzgerald]." The latter review accused Ellis of falling flat, attracting negative comparison to Martin Amis; both have "a flair for such perfect, surreal description" but "struggle to set it in an effective context."[27] Other writers attempting to gauge the book's reception also describe it as "mixed".[28] The Periscope Press deemed that the novel's reviews were mostly negative, citing Dr. Alison Kelly's article for The Guardian as the only counter-example, while deeming that it "still read more like restrained criticism than outright praise".[29] On the subject of reviews, British critic Mark Lawson notes the tendency for Ellis' reviews to be "unpredictable"; he cited the irony of favour amongst right-wing critics, and the extent to which the liberal media attack his work. Ellis himself, however, states that he "proudly" accepts the label of moralist. He also attributes some of the negative criticism that Imperial Bedrooms and Ellis' earlier works have received in the past to the earlier schools of feminist criticism; today, he observes young girls "reading the works correctly", opining the books shouldn't be read through the lens of "old school feminism." To that end, the author observes that older women reviewing Imperial Bedrooms in the US had issues with it, not least feelings of betrayal. He feels these are ironic because the book is in fact a critique of a certain kind of male perspective and behaviour.[11]

This book has its share of horror, not least a series of gangland slayings, but then dead bodies are to a Bret Easton Ellis novel what aspidistras are to George Orwell's: part of the scenery. More noticeable is the misting of melancholy that enshrouds LA's billboards and boulevards, and the mysterious crying fits that steal over its hero... Feelings? In a novel by Bret Easton Ellis? Whatever will his fans say?

Review Tom Shone, commenting on typical and atypical features of the new novel for The Sunday Times

Tom Shone, writing for The Sunday Times, praised the novel for its atypical qualities for Ellis, "known for his orgies of violence". Shone asks "Why is a new sequel to Less Than Zero... so moving?", noting the presence of "feelings" in the novel to be starkly different from Ellis' usual style. Touching on its personal qualities, Shone notes "If Lunar Park unspooled the atrocities of American Psycho back to their source, Imperial Bedrooms pulls the thread further and reaches Less Than Zero". The emotive energy in the new book is traced back to the last pages of Lunar Park as well; fellow writer Jay McInerney observes that "The last few pages of [Lunar Park] are among the most moving passages I know in recent American fiction [because]... Bret was coming to terms with his relationship with his father in that book."[24] Vice observes that the "final passages in both Imperial Bedrooms and Lunar Park pack a lot of emotional impact."[5] San Francisco Chronicle hails Imperial Bedrooms as "the very definition of authorly meta: Ellis is either so deeply enmeshed in his own creepy little insular world that he can't write his way out of it, or else he is such a genius that he's created an entire parallel universe that folds and unfolds on itself like some kind of Escher print."[18]

Regarding the book's achievement, Shone remarks "He now stands at year zero – creatively, psychologically." However, typical features of Ellis' earlier works remain intact; for example, in its depictions of violence.[24] Commenting on its self-referential aspects, Janelle Brown of the San Francisco Chronicle recommends "for his next endeavor, Ellis should stop worrying and start looking for the exit of his own personal rabbit hole."[18] The Buffalo News awarded the novel its Editor's Choice. Jeff Simon comments that it "brings an excessive Reaganesque flavor to Obama America". With regards to the novel's writing style, he comments "The first-person sentences run on and on, but the individual sections of the book are nothing if not minimal... ghastly narcissism or not, Bret Easton Ellis has a fictional territory all his own and, heaven forbid, a mastery there."[30] The Wall Street Journal on the other hand, described this prose style as "flat and fizzless".[23] Such is the book's violent aesthetic that, for Eileen Battersby of The Irish Times, "the book is closer to his remarkable third novel, American Psycho". She further compliments Ellis as "a bizarrely moral writer who specializes in evoking the amoral." Concerning his writing, she notes its "despair is blunt, factual and seldom approaches the laconic unease of JG Ballard."[16]

Following her positive comments, however, Battersby concludes negatively. The book is a "bleak performance... a tired study of the vacuous" with the feeling of an improvised screenplay being performed by an uncommitted cast. She sums that Ellis' novel "consists of too many doors being left slightly ajar, and not enough rooms, or opportunities, being fully explored."[16] Some critics have questioned the book's relevance to a contemporary audience. Dallas News poses the question, whether Imperial Bedrooms is "a story anyone is interested in anymore", because Ellis' "blunt, spare, journal-entry prose" is no longer, in 2010, "the backstage pass" it once was to the lives of "LA's rich and famous". Furthermore, Tom Maurstrad argues that since the 1980s, that decade has become a "go-to bargain bin for retro-trends and ready-made nostalgia, easy to package into fashion lines and TV shows". The review bemoans that the novel's theme, the dark side of Hollywood, is no longer a culture-shocking revelation, and that Ellis fails to capitalize on the narratorial conceit which it opens with. Maurstrad does highlight positive aspects, however. Ellis wisely "appropriates the unblinking brutality [of]... American Psycho, to add some dramatic heft to this anorexic update", making the sequel a "celebrity snuff film" to the earlier "backstage pass".[20] The Wall Street Journal damned the novel as "a dull, stricken, under-medicated nonstory that goes nowhere."[23] The Boston Globe reviewer opined that "Ellis is aiming for noir, for the territory of James Ellroy and Raymond Chandler, but ends up with an XXX-rated episode of Melrose Place."[31]

Andrew McCarthy, who played Clay in the 1987 Less than Zero film, described the novel as "an exciting, shocking conclusion... a surprising one." The actor praised Clay's character, citing a "wicked vulnerability" which the character covers up with alcohol, hostility, and its portrayal of a world "full of pain and suffering and unkindness" beneath the "glossy and shimmering and seductive" veneer of Hollywood. McCarthy described his experience of reading the book as like "revisiting an old friend", owing to the consistency of the characters' and Ellis' voices.[32]

Possible film adaptation

In May 2010, when MTV News first announced that Ellis had finished writing Imperial Bedrooms, the writer told them in interview that he had begun looking ahead to the possibility of a film adaptation, and felt that interpreting it as a sequel to the 1987 movie adaptation starring Andrew McCarthy, Robert Downey Jr., James Spader and Jami Gertz "would be a great idea".[7] Two months prior to the book's release, Less than Zero actor Andrew McCarthy stated it was "early days" in thinking about a potential film adaptation; McCarthy felt, however, that the novel would adapt well.[32] Because the characters in Imperial Bedrooms have been owned by 20th Century Fox since Ellis sold the film rights to Less than Zero, prospective film for Imperial Bedrooms rights revert to Fox. Ellis stated to Vice in June 2010 that he would be interested in writing the screenplay.[5] In July 2010 however, the author clarified to California Chronicle, saying "There's no deal, there's no one attached. There's been some vague talk among the cast members... As far as I know right now nothing's happening." Ellis opines that were Robert Downey Jr. to get involved, the film would move straight into production. However, remembering the adaptation process Less than Zero went through, he admits "I've learned to be cautious about saying oh they'll never turn this dark depraved character into any sort of interesting Mulholland Drive, David Lynch kind of movie, but I could be totally wrong about that. I don't know."[6]

References

- ↑ "Imperial Bedrooms by Bret Easton Ellis". Random House. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Gauthier, Robert (June 11, 2010). "Bret Easton Ellis: interview outtakes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kellogg, Carolyn (June 13, 2010). "Bret Easton Ellis' wilted innocence". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Ellis, Bret Easton (April 18, 2019). White. April 18, 2019. ISBN 978-1-5290-1241-5. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Person, Jesse (June 2010). "In the magazine: Bret Easton Ellis". Vice.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baker, Jeff (July 2010). "Q&A: Bret Easton Ellis talks about writing novels, making movies". California Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- 1 2 Carroll, Larry (April 14, 2009). "Bret Easton Ellis Finishes 'Less Than Zero' Sequel, Wants Robert Downey Jr. Back". MTV News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ↑ Connolley, Brendon (April 14, 2009). "Robert Downey Jr. Back For Less Than Zero 2? Brett Easton Ellis Suggests So". Slashfilm.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ↑ Graham, Mark (April 14, 2009). "Bret Easton Ellis Wants to Reunite Less Than Zero Cast for a Sequel". New York. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ↑ Lewis, Hilary (April 14, 2009). "Does Bret Easton Ellis Want Robert Downey, Jr. To Be An Addict Again?". The Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ellis, Bret Easton (July 14, 2010). "Bret Easton Ellis and Camille Silvy". Front Row (Interview: Audio). Interviewed by Mark Lawson. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on October 16, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ↑ Bret Easton Ellis [@BretEastonEllis] (November 4, 2010). ""They had made a movie about us." The first sentence of Imperial Bedrooms" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ Imperial Bedrooms Archived February 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Randomhouse.biz

- 1 2 3 4 Eichenberger, Bill (June 15, 2010). "Bret Easton Ellis puts his seminal characters into 'Imperial Bedrooms'". Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- 1 2 Eisinger, Dale W. (June 14, 2010). "Two Times' Zero". New York Press. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Battersby, Eileen (June 12, 2010). "A bulletin from the outer fringes". Irish Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Gordinier, Jeff (June 2010). "BRET EASTON ELLIS: THE ETERNAL BAD BOY". Details. Archived from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown, Janelle (June 20, 2010). "'Imperial Bedrooms,' by Bret Easton Ellis". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Akbar, Arifa (July 9, 2009). "Imperial Bedrooms, By Bret Easton Ellis". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on September 28, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Maurstrad, Tom (June 13, 2010). "Book review: 'Imperial Bedrooms' by Bret Easton Ellis". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ↑ McGregor, Michael (June 26, 2010). "Fiction review: 'Imperial Bedrooms' by Bret Easton Ellis". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ↑ Kelly, Alison (June 27, 2010). "Imperial Bedrooms by Bret Easton Ellis". guardian.co.uk, The Observer. London. Archived from the original on June 30, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Fischer, Mike (June 17, 2010). "Zero Progress". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Shone, Tom (June 13, 2010). "Once more, with feeling". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- 1 2 Crace, John (July 6, 2010). "Imperial Bedrooms by Bret Easton Ellis". The Guardian.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ "Critical eye: book reviews roundup". The Guardian. London. June 26, 2010. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Culture Vulture: reviews round-up". New Statesman. July 5, 2010. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ↑ Wengen, Deidre (June 21, 2010). "Book buzz: 'Imperial Bedrooms' by Bret Easton Ellis". PhillyBurbs.com. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Enfant more dull than terrible". The Periscope Press. June 29, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ↑ Simon, Jeff (June 20, 2010). "Editor's Choice". The Buffalo News. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ↑ Atkinson, Jay (July 4, 2010). "Less than zero: Bret Easton Ellis's sequel misses". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on July 8, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- 1 2 "Are you excited for the 'Less Than Zero' sequel?". USA Today. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original on April 26, 2010. Retrieved May 8, 2010.