Inés Suárez | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1507 Plasencia, Extremadura, Spanish Empire |

| Died | 1580 (aged c. 73) |

| Spouse | Rodrigo de Quiroga |

Inés Suárez, (Spanish pronunciation: [iˈnes ˈswaɾes]; c. 1507 – 1580) was a Spanish conquistadora who participated in the Conquest of Chile with Pedro de Valdivia, successfully defending the newly conquered Santiago against an attack in 1541 by the indigenous Mapuche.

Early life

Suárez was born in Plasencia, Extremadura, Spain in 1507.[1] She came to the Americas approximately in 1537, around the age of thirty. It is generally assumed that she was in search of her husband Juan de Málaga, who had left Spain to serve in the New World with the Pizarro brothers. After a long time of continuous searching in numerous South American locations, she arrived in Lima in 1538.

Suárez's husband had died before she had reached Peru (she told a compatriot that he died at sea) and the next information that is known of her is in 1539, when she applied for and was granted, as the widow of a Spanish soldier, a small plot of land in Cuzco and encomienda rights to a number of Indians.

Shortly afterward, Suárez became the mistress of Pedro de Valdivia, the conqueror of Chile. The earliest mention of her friendship with Valdivia was after he returned from the Battle of Las Salinas (1538). Although they were from the same area of Spain and at least one novelist relates a tale of long-standing love between them, there is no real evidence that they had met prior to her arrival in Cuzco.

Conquest of Chile

In late 1539, over the objections of Francisco Martínez and encouraged by some of his captains, Valdivia, using the intermediary services of a Mercedarian priest, requested official permission for Suárez to become a part of the group of 12 Spaniards he was leading to the South. Francisco Pizarro, in his letter to Valdivia (January 1540) granting permission for Suárez to accompany Valdivia as his domestic servant, addressed the following words to Suárez, "...as Valdivia tells me, the men are afraid to go on such a long trip and you very courageously put yourself in the face of that danger..."

During the long and harrowing trip to the south, Suárez, who was the only white woman on the expedition, in addition to caring for Valdivia and treating the sick and wounded, found water for them in the desert, and saved Valdivia when one of his rivals tried to undermine his enterprise and take his life. The natives, having already experienced the incursions of the Spaniards, (Diego de Almagro, 1535–1536) burned their crops and drove off their livestock, leaving nothing for Valdivia's band and the animals which accompanied them. Suarez was a cook and a nurse for the majority of the expedition. She was personally in charge of growing crops and the maintaining of the group's livestock. Whenever necessary, she would pick up the sword and fight alongside the rest of the men.[2]

In December 1540, eleven months after they left Cuzco, Valdivia and his band reached the valley of the Mapocho river, where Valdivia was to establish the capital of the territory. The valley was extensive and well populated with natives. Its soil was fertile and there was abundant fresh water. Two high hills provided defensive positions. Soon after their arrival, Valdivia tried to convince the natives of his good intentions, sending delegations bearing gifts for the caciques.

The natives kept the gifts but, united under the leadership of Michimalonco, attacked the Spaniards and were at the point of overwhelming them. Suddenly, the natives threw down their weapons and fled. Captured Indians declared that they had seen a man, mounted on a white horse and carrying a naked sword, descend from the clouds and attack them. The Spaniards decided it was a miraculous appearance of Santo Iago (Saint James the Greater who had already been seen during the Reconquista at the battle of Clavijo) and, in thanks, named the new city Santiago del Nuevo Extremo. The city was officially dedicated on February 12, 1541.

First destruction of Santiago

In August 1541, when Valdivia was occupied on the coast, Suárez uncovered another plot to unseat him. After the plotters were taken care of, Valdivia turned his attention to the Indians and he invited seven caciques to meet with him to arrange for the delivery of food. When the Indians arrived, Valdivia had them held as hostages for the safe delivery of the provisions and the safety of outlying settlements. On the September 9, Valdivia took forty men and left the city to put down an uprising of Indians near Aconcagua.

Early on the morning of September 10, 1541, a young yanakuna brought word to Captain Alonso de Monroy, who had been left in charge of the city, that the woods around the city were full of natives. Suárez was asked if she thought that the Indian hostages should be released as a peace gesture. She replied that she saw it as a bad idea; if the Indians overpowered the Spaniards, the hostages would provide their only bargaining power. Monroy accepted her counsel and issued a call for a council of war.

Just before dawn on September 11, mounted Spaniards rode out to engage the Indians, whose numbers were estimated first at 8,000 and later at 20,000, and who were led by Michimalonco. In spite of the advantage of their horses and their skill with their swords, by noon the Spaniards were pushed into a retreat toward the east, across the Mapocho River; and, by mid-afternoon, they were backed up to the plaza itself.

All day the battle raged. Fire arrows and torches set fire to most of the city; four Spaniards were killed along with a score of horses and other animals. The situation became desperate. The priest, Rodrigo González Marmolejo, said later that the fight was like the Day of Judgment for the Spaniards and that only a miracle saved them.

All day Suárez had been carrying food and water to the fighting men, nursing the wounded, giving them encouragement and comfort. The historian Mariño de Lobera wrote of her activities during the battle:

...seeing that the business was going to a beaten defeat and victory was being declared by the Indians, she put a coat of mail over her shoulders and in this way, she went out to the square and stood in front of all the soldiers, encouraging them with words of such weight that he was more of a valiant captain than a woman exercised on his pad. And she went among them, she told them that if they felt fatigued and if they were wounded she would cure them with her own hands... she went where they were, even among the hooves of the horses; and she did not just cure them, she animated them and raised their morale, sending them back into the battle renewed... one caballero whose wounds she had just treated, was so tired and weak from loss of blood that he could not mount his horse. This woman was so moved by his plea for help that she put herself into the midst of the fray and helped him to mount his horse.[3]

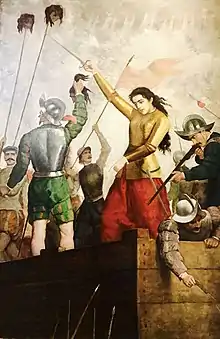

Suárez recognized the discouragement of the men and the extreme danger of the situation; she offered a suggestion. All day the seven caciques who were prisoners of the Spaniards, had been shouting encouragement to their people. Suárez proposed that Spaniards decapitate the seven and toss their heads out among the Indians in order to frighten them. There was some objection to the plan, since several men felt that the fall of the city was imminent and that the captive caciques would be their only bargaining advantage with the Indians. Suárez insisted that hers was the only viable solution to their problem. She then went to the house where the chieftains were guarded by Francisco Rubio and Hernando de la Torre and gave the order for the execution. Mariño de Lobera tells that the guard, La Torre, asked, "In what manner shall we kill them, my lady?" "In this manner," she replied, and, seizing la Torre's sword, she herself cut off the heads.[4] After the seven were decapitated and their heads thrown out among the Indians, Suárez donned a coat of mail and a helmet and, throwing a hide cloak over her shoulders, she rode out on her white horse. According to an eyewitness, "...she went out to the plaza and put herself in front of all the soldiers, encouraging them with words of such exaggerated praise that they treated her as if she were a brave captain,...instead of a woman masquerading as a soldier in iron mail."[5]

In a second version of these events, Gerónimo de Bibar points out that, on the same occasion, Inés grabbed a sword and, heading towards the location where the Spaniards had some indigenous caciques, killed them.[6] She then goes on to be extremely disappointed in the lack of bravery on the part of the soldiers and commands them to at least move the bodies in the view of the attacking armies. She considered herself to be above these men in masculinity and looked down on the mental weakness of her fellow soldiers.[7] One of the knights, Gil Gonzalez de Avila, suffered a terrible blow that made him bleed a lot. Seeing that he was. unable to mount his horse, Ines went up to the knight and stopped all the blood coming from his veins, allowing him to continue the fight. Seeing her medical expertise in action, the other fighting soldiers saw and were emboldened by her courage.[8] In another version of the recounted events, Ines goes up to the Spaniard and tells him kill the hostages in the way the El Cid would have killed Muslims in the Reconquista.[9]

The Spaniards took advantage of the confusion and disorder engendered among the Indians by the gory heads, and spurred on Suárez, succeeded in driving the now disordered Indians from the town. One historian wrote, "The Indians said afterward that the Christians would have been defeated were it not for a woman on a white horse."

The notion that Ines ordered the killing of the seven Indian leaders in Santiago while the city was under attack is questioned by some scholars. Some say that it is because Valvidia never told King Charles V about this in his letters.[10]

In 1545, in recognition of her courage and valor, Valdivia rewarded Suárez with an encomienda. His testament of dedication said in part:

...in battle with the enemies who did not take into account the caciques who were our prisoners, they that were in the most central place - to which the Indians came, ...throwing themselves on you, and you, seeing how weakened your beleaguered forces were then, you made them kill the caciques who were prisoners, putting your own hands on them, causing the majority of the Indians to run away and they left off fighting when they witnessed the evidence of the death of their chieftains; ...it is certain that if they had not been killed and thrown among their countrymen, there would not be a single Spaniard remaining alive in all this city... by taking up the sword and letting if fall on the necks of the cacique prisoners, you have saved all of us.

Later life

Suárez continued to live openly with Pedro de Valdivia, until the time of his trial in Lima. One of the charges levelled against him was that he, being married, openly lived with her "...in the manner of man and wife". Suarez quickly took action and hired some of the best advisors in the Empire to help Valvidia fight off these charges. She convinced the Viceroy of Peru, Pedro de la Gasca, to use his powers as viceroy give to absolve Valvidia of any crimes in the Viceroyalty.[11] In exchange for being freed, and his confirmation as Royal Governor, he was forced to relinquish her and to bring to Chile his wife, Marina Ortiz de Gaete, who only arrived after Valdivia's death in 1554. He was also ordered to marry Suárez off.

Suárez was married in 1549 to Valdivia's captain, Rodrigo de Quiroga, when she was 42 and the groom was 38. After her marriage, she led a very quiet life, dedicated to her home and to charity. Together with her husband, she contributed to the construction of the temple of La Merced and the hermitage of Monserrat, in Santiago.[12] She was held in great esteem in Chile, as being a valiant woman and a great captain. While she knew that plazas and towns would be named after her, she personally lamented that people would never remember the hundreds of women involved in the founding of Chilean towns. Eventually, after the death of Valdivia, her husband twice became Royal Governor himself, in 1565 and 1575. They both died in Santiago de Chile, within months of each other, in 1580.

Suárez's legacy

Suárez is seen as a symbol of a Chilean woman standing up to authority like Paula Jaraquemada and Javiera Carrera. She is still mentioned as a role model to contemporary protestors against mistreatment.[13]

Suárez is the main character in several historical novels, such as "Inés y las raíces de la tierra", ("Inés and the roots of the land"), by María Correa Morande (ZigZag, 1964), "Ay Mamá Inés - Crónica Testimonial" ("Woe, Momma Inés - Testimonial Chronicle") (Andres Bello, 1993) by Jorge Guzmán, and "Inés of My Soul" (Spanish: Inés del alma mía) by Isabel Allende (HarperCollins, 2006). In her author's note Allende wrote: "This novel is a work of intuition, but any similarity to events and persons relating to the conquest of Chile is not coincidental". Allende's novel has been adapted as a Spanish-Chilean television series in 2020. Elena Rivera (27-year-old during shooting) plays Suárez.[14]

Further reading

Henderson, James D, Linda Roddy (1978). Ten notable women of Latin America. pp. 23–48. OCLC 641752939.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mariño de Lobera, Pedro. "VIII". Crónica del Reino de Chile (in Spanish).

...una señora que iba con el general llamada doña Inés Juárez, natural de Plasencia y casada en Málaga, mujer de mucha cristiandad y edificación de nuestros soldados...

- ↑ Portocarrero, Melvy. "Inés Suárez: La Conquistadora de Chile, Una Mujer Que Rompe Con Las Barreras de Género." Letras Femeninas, vol. 36, no. 2, 2010, pp. 229–36. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23022111. Accessed 27 May 2023.

- ↑ Mariño de Lobera, Pedro. "XLIII". Crónica del Reino de Chile (in Spanish).

- ↑ Mariño de Lobera, Pedro. "XV". Crónica del Reino de Chile (in Spanish).

...Mas como empezase a salir la aurora y anduviese la batalla muy sangrienta, comenzaron también los siete caciques que estaban presos a dar voces a los suyos para que los socorriesen libertándoles de la prisión en que estaban. Oyó estas voces doña Inés Juárez, que estaba en la misma casa donde estaban presos, y tomando una espada en las manos se fué determinadamente para ellos y dijo a los dos hombres que los guardaban, llamados Francisco Rubio y Hernando de la Torre que matasen luego a los caciques antes que fuesen socorridos de los suyos. Y diciéndole Hernando de la Torre, más cortado de terror que con bríos para cortar cabezas: Señora, ¿de qué manera los tengo yo de matar? Respondió ella: Desta manera. Y desenvainando la espada los mató a todos...

- ↑ Mariño de Lobera, Pedro. "XV". Crónica del Reino de Chile (in Spanish).

Viendo doña Inés Juárez que el negocio iba de rota batida y se iba declarando la victoria por los indios, echó sobre sus hombros una cota de malla y se puso juntamente una cuera de anta y desta manera salió a la plaza y se puso delante de todos los soldados animándolos con palabras de tanta ponderación, que eran más de un valeroso capitán hecho a las armas que de una mujer ejercitada en su almohadilla.

- ↑ "Digital edition based on Crónicas del Reino de Chile Madrid, Atlas, 1960, pp. 227-562, (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles; 569-575)."

- ↑ "Digital edition based on Crónicas del Reino de Chile Madrid, Atlas, 1960, pp. 227-562, (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles; 569-575)."

- ↑ "Digital edition based on Crónicas del Reino de Chile Madrid, Atlas, 1960, pp. 227-562, (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles; 569-575)."

- ↑ "Digital edition based on Crónicas del Reino de Chile Madrid, Atlas, 1960, pp. 227-562, (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles; 569-575)."

- ↑ "Digital edition based on Crónicas del Reino de Chile Madrid, Atlas, 1960, pp. 227-562, (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles; 569-575)."<

- ↑ "Digital edition based on Crónicas del Reino de Chile Madrid, Atlas, 1960, pp. 227-562, (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles; 569-575)."

- ↑ Portocarrero, Melvy. "Inés Suárez: La Conquistadora de Chile, Una Mujer Que Rompe Con Las Barreras de Género." Letras Femeninas, vol. 36, no. 2, 2010, pp. 229–36. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23022111. Accessed 27 May 2023.

- ↑ Margaret Power (1 November 2010). Right-Wing Women in Chile: Feminine Power and the Struggle Against Allende, 1964-1973. Penn State Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-271-04671-6.

- ↑ "Inés del alma mía. Serie TV". Fórmula TV (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2020.

Sources

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 321–322.

- Amunátegui, Miguel Luis (1913). Descubrimiento i conquista de Chile (PDF) (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Imprenta, Litografía i Encuadernación Barcelona. pp. 181–346.

- Barros Arana, Diego (1873). Proceso de Pedro de Valdivia i Otros Documentos Inéditos Concernientes a Este Conquistador (PDF) (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Librería Central de Augusto Raymond. p. 392.

- Ercilla, Alonso de. La Araucana (in Spanish). Eswikisource.

- Góngora Marmolejo, Alonso de (1960). Historia de Todas las Cosas que han Acaecido en el Reino de Chile y de los que lo han gobernado (1536-1575). Crónicas del Reino de Chile (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Atlas. pp. 75–224.

- Mariño de Lobera, Pedro (1960). Fr. Bartolomé de Escobar (ed.). Crónica del Reino de Chile, escrita por el capitán Pedro Mariño de Lobera... reducido a nuevo método y estilo por el Padre Bartolomé de Escobar (1593). Crónicas del Reino de Chile (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Atlas. pp. 227–562.

- Maura, Juan Francisco. 2005.Españolas de ultramar en la historia y en la literatura: aventureras, madres, soldados, virreinas, gobernadoras, adelantadas, prostitutas, empresarias, monjas, escritoras, criadas y esclavas en la expansión ibérica ultramarina (siglos XV a XVII) http://parnaseo.uv.es/Editorial/Maura/INDEX.HTM |=PDF online facsimile|others=Hernando Maura (illus.) |location=Valencia, Spain |publisher=Colección Parnaseo — Universitat de València

- Medina, José Toribio (1906). Diccionario Biográfico Colonial de Chile (PDF) (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Elzeviriana. pp. 1, 006.

- Valdivia, Pedro de (1960). Cartas. Crónicas del Reino de Chile (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Atlas. pp. 1–74.

- Vivar, Jerónimo de (1987). Crónica y relación copiosa y verdadera de los reinos de Chile (1558) (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Arte Historia Revista Digital. Archived from the original on 2008-05-26.

- "Inés de Suárez" (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Diario La Tercera. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- "Inés Suárez". Biografía de Chile (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 January 2009.